Developing documentation with DocBook

It so happened that in our projects the maintenance of technical documentation rests entirely on the shoulders of the developers, according to the principle: made changes to the project code - updated the documentation. The documentation itself was a collection of Word documents that were stored along with the source code for VCS. This approach to the development organization has existed for a long time, but a couple of years ago we decided to take care of the possibility of maintaining project documentation using tools other than MS Office.

There were several reasons for this:

- The first and probably the most important one is frequent conflicts when editing files together.

- The second reason is that although there were a lot of documents, they all had a similar structure and overlapped in many respects in terms of content (due to the architecture of the project). And as true programmers, we were not happy with the “duplication” of text.

- And finally, the eternal struggle with design styles.

All these problems were superimposed on each other and made of this already not so beloved process of updating the documentation an unbearable punishment in terms of severity. It happened that after several hours of writing, with a sense of accomplishment, you try to “fill in” your changes in SVN and you receive sad news that someone was faster than you or you simply simply forgot to update before starting work. In any case, this meant that the smoke break would have to be postponed a little. In addition to the text, it was necessary to pay attention to design styles that, with fairly enviable regularity, for some reason “broke” (for example, the list was numbered from the beginning, to the place where it would continue, etc.). And not all of these “breakdowns” turned out to be easily eliminated,

Thus, our alternative to MS Word was to satisfy the following criteria:

- Text format for document storage - for convenient work with it in VCS.

- Support for extensive design and styling of the document.

- The ability to decompose the final document into fragments - for reuse.

- Ability to publish the final document in various formats.

As a result of a long search, we realized that there are not so many solutions that satisfy our requirements: DITA and DocBook. DITA immediately seemed to us too “powerful” and difficult to transition, but on DocBook we decided to stop. Generally speaking, the search for an alternative solution was very gradual and before we realized that “one cannot live on like that” and a complete transition to DocBook, more than one day passed and a large number of experiments were carried out on what was in our hands at that moment. First of all, we tried to store documents in WordML format, which to some extent solved the problem of merging changes - now the merger did not always end in conflict, but manual resolution of conflicts in the markup was very uncomfortable. Also tried to split the documents into fragments, thereby reducing the possibility of conflict changes and try to reuse them. The idea was very unsuccessful. And so gradually, through trial and error, they all the same decided to completely switch to DocBook, since in our opinion, he should have eliminated all our problems.

What is a DocBook?

Suddenly, if someone didn’t know, DocBook is a standard for describing a document and does nothing useful except to standardize content. Moreover, the standard is quite old, and many, for some reason, are already considered obsolete.

Writing a document in DocBook format is very similar to working with HTML, only its own set of tags and rules for their use are used.

First Chapter Hello world! This example demonstrates the description of a book consisting of one chapter with the name “First Chapter” containing a paragraph with the text “Hello Word!”. A complete list of tags, as well as examples of their application, can be found on the project website www.docbook.org . On my own, I want to note that the set of tags for describing the content is very (even very very) large, but in everyday work we use about 20.

Convert DocBook Document

In order to bring our DocBook document to some format suitable for reading or printing, you must use a transformer (or even a conveyor of several transformers one after another), which, based on the contents of the document and, usually, the design styles, will form the final document.

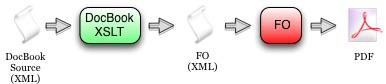

DocBook -xsl is usually used for transformation (although there are more exotic ways). Out of the box, it already supports several document formats - html, xsl-fo, manpages, etc. If you need a different presentation format, you can continue the chain of conversions. So to get a document in PDF usually use the following scheme:

And here the fun begins. Styles implemented in DocBook-xsl by default allow you to get a document that looks normal in appearance, but usually, their customization is still required.

The docbook-xsl style developers took care of this feature and implemented special mechanisms for this:

- The most common parameters for creating a document for each of the supported formats are taken out in a separate param.xsl file and for each of them there is a more or less detailed description.

- There are special patterns for creating custom patterns.

- The presence of special, empty by default templates for their subsequent redefinition.

Most often, to control the process of forming a document, an own XSL root style is developed, the so-called “Driver” in which fine-tuning of all other transformation parameters is already carried out. Since each final format in DocBook-xsl is represented by its own set of templates, then the “driver” for each of them needs to be written separately. For example, we use two final document presentation formats (xsl-fo and htmlhelp) and, accordingly, we have two “drivers” and two sets of redefined styles.

Choosing xslt and fo processor

To work with DocBook-xsl, you need an xslt processor supporting xslt version 1.0. (There is an implementation of docbook-xsl for version 2.0, but I don’t know how stable it is). Currently, there are many working solutions for a wide variety of platforms - so there should not be a problem with this. In our projects we use saxon, although the old version is Saxon 9.1.0.8J, since the last free freeware support for EXSLT extensions is completely removed (necessary for document profiling) and there was no certainty that the saxon extension for supporting syntax highlighting that comes with styles will work in a new one.

To generate documents from xsl-fo, you need an fo processor. Here things are a little worse - from the working processors I personally tried two FOP (opensource) and XEP (RenderX XEP Engine - a bit paid). There are several more working fo processors, but I personally have not tried working with them and can not say anything about them.

The main plus of FOP is that it is free, but there is also a minus - from the “box” it does not support the Russian language. When we first met him, we were not able to get him to work with the Cyrillic alphabet. Oddly enough, there are a lot of articles about this on the Internet, but all of them were either very old (where it was suggested to rebuild FOP with the necessary fonts) or contained errors that did not allow to achieve the desired result. In the end, everything turned out to be very simple, but our choice already fell on XEP. XEP works fine with the Cyrillic alphabet immediately after installation and, in principle, does not require any additional configuration, but costs $ 400 - and the desktop version. I can’t judge the difference in rendering quality, but you can compare for your own interest (in the example there are files collected by both fo-processors).

Customization Style

For a quality setting of styles, you need to know a little the xsl conversion language, as well as the markup language of the final document. Unfortunately, at the time of the transition to DocBook, our team did not have such competency, and therefore the setup took us a sufficient amount of time - especially for the FO format. Although there are a large number of sites on the network with information on this (especially valuable in my opinion, “ DocBook XSL: The Complete Guide ”), it’s very difficult to get a complete picture right away. Therefore, I decided to act on the principle - “it's better to see once than hear a hundred times” and prepared an example of style for xsl-fo (about the same as we use in our projects) along with the source text of this article and customized FOP.

The only point I want to stop at and which, at first, can be confusing is to configure the fonts and language of the document. By default, fonts that do not support the Cyrillic alphabet are included in xsl-fo, and if you do not override these parameters or make a mistake in them (you need to make sure that the fo processor is configured to work with the specified fonts), then we will most likely get an unreadable output from the fo processor document. The language of the document affects the creation of AutoText for the names of the elements of the book (Chapter, Book, etc.). In principle, setting only these parameters will already allow you to get the “correct” document. Also, most likely there will be a desire to change the appearance of the cover page of the document. This can be done using a template specially prepared in docbook-xsl. To do this, you need to define your version of the file "/fo/titlepage.templates.

Conclusion

The full transition to DocBook took us a lot of time. Firstly, it was necessary to bring to him the already written documentation. Here we tried different utilities like AntiWord, but due to the large number of artifacts, it was decided to do it manually (artifacts were obtained both due to formatting errors in the original document, and because of the peculiarities of the translation scripts). Also, it took us a lot of time to develop our own design styles, search for an environment for developing documents (as a result, we decided on NotePad ++) and environment settings. It seemed a simple task, but when it was implemented, they constantly ran into some problems. Unfortunately, there is not much information on DocBook, and if we talk about the Russian-language segment, then practically none at all. But in the end, we were satisfied.

Since our team switched to maintaining technical documentation in DocBook more than one year has passed, and we no longer imagine any other option. All that we wanted to achieve by switching to DocBook - we achieved:

- They forgot what conflicts are in the documentation when working in VCS, even when using GitFlow (with the same caveat as at the beginning of the article: made changes - reflected in the documentation).

- Almost completely got rid of duplication of the same text in different documents. Thanks to DocBook's profiling, it turned out to make the document more flexible, and writing documentation less tedious work. This is the main sense of proportion, because the very complicated decomposition of the original document greatly complicates the navigation on it and subsequent editing.

- We almost forgot how to format documents in Word, or rather just forgot how to format. Now the development of documentation is only a writing of the text of the document.

- Great scope for creativity in terms of integration into the overall software development process.

Naturally, in addition to the pros, there are also disadvantages:

- The most pressing problem at the moment is the interaction with other divisions of the company. For obvious reasons, only our team switched to DocBook, everyone else uses MS Word, and when we need to exchange data, we have to do it manually. Fortunately, this is very rare, and is usually limited to a couple of paragraphs of text.

- The complexity of implementing some non-standard DocBook approaches to document formatting, in particular, there is often a need to expand several pages in landscape orientation, but still have not learned how to do this (to our shame) and we have to bypass this moment somehow differently. But I am 100% sure that this can be done, and therefore the unresolved nature of this problem can be explained by a less urgent need. For example, when we needed to insert formulas into a document, it took less than noon to screw MathML.

And the purpose of this article is to convey to readers who are developing technical documentation in office programs that there are more suitable tools. For those who have been looking towards DocBook or DITA for some time, giving them a boost and hints for the transition is the hardest part to start! It would also be very interesting to hear what approaches were adopted by other teams and their implementation experience.

List of references:

Example: