Is it hard to concentrate? Maybe it's not your fault

- Transfer

The last significant event in the year when Silicon Valley only apologizes was the technological equivalent of “drinking wisely” or “cautious excitement” of the gaming industry. In August, Facebook and Instagram announced the introduction of new tools for users, with which you can set time limits on both platforms, as well as a panel to monitor daily activity. They did this after Google, who had previously presented the tools of the so-called “Digital Well-being” .

Technological companies, acting in this way, seem to imply that spending time on the Internet is not an expedient, healthy habit, but an enjoyable vice, which, if not controlled, can turn into an unattractive addiction.

Capturing our attention more than they ever dreamed of, these companies now cautiously admit that it is time to return some of this attention back so that we can look into the eyes of our children who have not yet been treated with Clarendon or Lark filters; watch a movie in the cinema; or, which goes against Apple’s watch advertising , go surfing - God forbid - not mentioning anywhere.

“Emancipating human attention can be a moral and political battle defining our time,” writes James Williams, a 36-year-old technologist who became a philosopher and author of the recently published book Stand Out of Our Light .

Who does not know about this, as not Williams. During his ten years in Google, he was engaged in contextual advertising, helping to improve the powerful, data-based advertising model. Gradually, he began to feel that his life, as he had known it before, began to collapse. “It’s as if the earth has started to leave from under the feet,” he writes.

And, most likely, he would not be surprised by the increasing incidence of attention disorders, such as with Pablo Sandoval, who was the third baseman in the Red Sox, and in the middle of the game decided to check his Instagram (for which he was suspended by the club). Or the incident with Patty Lupon , which also occurred in 2015, when the actress took the phone from the girl in the hall.

Williams compares modern technology with the “whole army of airplanes and tanks” designed to catch and hold our attention. And this army is winning. We spend whole days chained to the screens, our thumb twitches in the subway and elevators or when we glance at the traffic lights.

At first we are proud of it, and then we regret the habit of having the so-called second screen when one monitor is no longer enough, and, for example, we watch the latest news on the phone while we watch TV.

A study conducted by Nokia in 2013 found that we test our phones on average 150 times a day. But we touch them 2617 times a day - according to a study in 2016, which was organized by the company Dscout.

Apple confirms that users remove the lock from their iPhones about 80 times a day. Now screens have appeared where they have never been before: on the tables at McDonald's; in the locker rooms where we are most vulnerable; in the back of a taxi. For only $ 12.99 you can buy an iPhone case for a pram ... or two (shudders).

These are us: glazed eyes, an open mouth, a crooked neck, caught in a dopamine loop and pulled into an information bubble. Our attention is sold to advertisers, along with our data, and returned to us back tattered and shattered.

You get chaos

Williams speaks on Skype from his home in Moscow, where his wife, who works at the UN, was sent on a one-year business trip.

By origin from Abilene (Texas), he began to work at Google in that period, which can still be called early, and when the company in its idealism resisted an existing advertising model. Williams left Google in 2013 to conduct research for a doctoral degree at Oxford on the philosophy and ethics of persuading attention to design.

Now Williams is worried about "interned" people losing the meaning of life.

“You pull out the phone to do something, and you are distracted, and after 30 minutes you find yourself doing a dozen other things, except for the one for which the phone was originally taken. At this level, there is fragmentation and confusion, he says. “But it also seemed to me that at the long-term level there is something else that is difficult to keep in view: the perspective of what you are doing.”

He knew that among his colleagues was not the only one who experienced this. Speaking at a technology conference in Amsterdam last year, Williams asked about 250 developers in the room: “How many of you want to live in the world you create? In a world where technology fights for your attention? ”

“ Not a single hand has risen, ”he says.

Williams is far from the only example of how a former big-tech soldier (if you continue the army metaphor) is now trying to bring his danger to clear water.

At the end of June, Tristan Harris, a former developer of Google, took the stage at the Aspen Ideas Festival to warn us that at least "existential threat" hangs on us from our own gadgets.

Red and thin, 34-year-old Harris has played an informant since he left Google five years ago. He opened the Human Technology Center in San Francisco and travels around the country, appearing in authoritative shows and podcasts, for example, in “60 Minutes” and “Awakening”, as well as at glamorous conferences, as in Aspen, for stories about how technologies against which it is impossible to resist.

He likes the chess analogy. When Facebook or Google directs the attention of their “supercomputers” towards our consciousness, he says, “this is check and check.”

In the innocent days of 2013, when Williams and Harris were still working at Google together, they met in conference rooms and outlined their thoughts on the lecture boards: a club of two concerned at the epicenter of the economy of attention.

Since then, the views of both have become larger and more urgent. The constant pressure of technology on human attention concerns not only the loss of time of our so-called “real lives” on online entertainment. Now, they say, we risk completely losing our moral orientation.

“Technology is changing our ability to understand what is true, so we have less and less understanding of the shared truth, the shared point of view with which we all agree,” Harris says the day after her performance in Aspen. “When there is no shared truth or shared facts, you get chaos ... And people can take control in their own hands.”

Of course, companies can also make a profit out of it - big and small. Of course, there was a whole industry to combat the advent of technology. Once free pleasures, for example, a short day’s sleep, are now monetized with hourly rates. Those who used to relax with monthly magazines, now download meditation applications with an instructor, for example, Headspace ($ 399.99 for a lifetime subscription).

The HabitLab app , developed at Stanford, behaves aggressively every time you get to the red zone of Internet consumption - defined by you. Reddit absorbs your daytime? Choose between a “minute killer” that will turn on a strict 60-second timer, and a “freezing screen” that creates an end to the endless list - and you will be thrown away when you press a button.

Like Moment , this app keeps track of your phone’s time and sends embarrassing notifications to you or your loved ones, telling you in detail how much time was spent today on Instagram. To do your job, HabitLab knows your behavior quite well, which leads to confusion. Obviously, now we need phones to save us from phones.

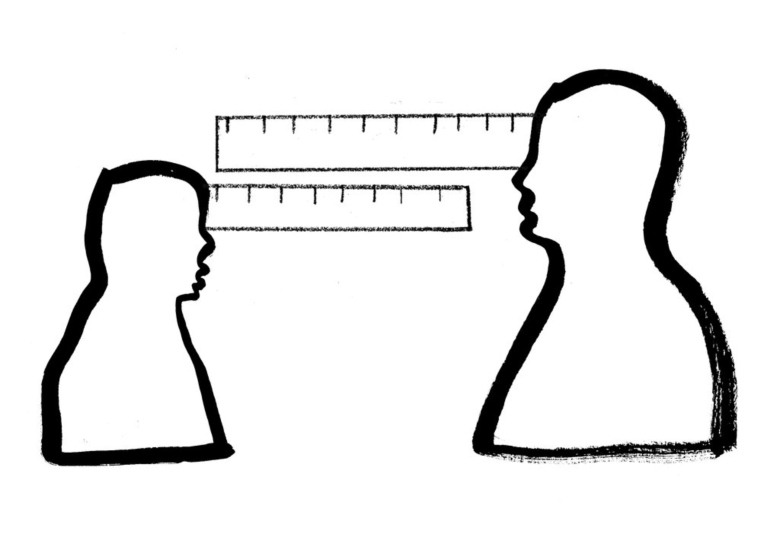

Researchers have long been aware that there is a difference between “downward” attention (volitional, effortless decisions that we make to pay attention to something of our choice) and “upward” attention when it is involuntarily captured by what happens. around us: a rumble of thunder, the sound of a shot or a tempting sound signal that notifies you of another message on Twitter.

But many of the most important questions remain unanswered. In the first position on this list remains such a mystery as "the relationship between attention and our conscious perception of the world." This is what Jesse Riesman, a neuroscientist, whose laboratory at the University of California at Los Angeles studies attention and memory tells about.

The consequences for our tormented neurons from the time spent at the screen are also unclear.

“We do not understand how modern technology and cultural change affect our ability to maintain focus on our goals,” says Dr. Riessman.

Britt Anderson, a neuroscientist at the University of Waterloo in Canada, came to the point that in 2011 he called his scientific work as "There is no such thing as attention."

Dr. Anderson said that scientists used the word “attention” to denote such different characteristics - attention span, attention deficit, selective attention, spatial attention - that in essence it became meaningless, and at that moment when the word itself is more relevant than ever or.

Are the children ... okay?

Although attention probably does not exist, many of us mourn his demise. For example, Mrs. Lupon and other people, including university professors, who are in charge of classrooms.

Katherine Hales, an English teacher at the University of California at Los Angeles, wrote about the change she noticed in students: when “deep attention”, a state of purposeful concentration that can last several hours changes to “hyper-attention” that jumps from one goal to the other, and prefers to superficially get acquainted with a lot of things, rather than deeply exploring one thing.

At Columbia University, where every student must complete a required course and read between 200 and 300 pages each week, teachers discuss how to deal with a marked change in students' ability to cope with assignments. Lisa Hollibo, the dean of academic planning for Colombia, says that the overall required course remains unchanged, but "we constantly think about how to teach when attention sustainability has changed in the last 50 years."

It was estimated that in the 90s, from 3 to 5% of American schoolchildren had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In 2013, this number reached 11% and continues to grow, according to data from a national study of children's health.

Nick Siver, a 32-year-old professor of anthropology at Tufts University, has just completed his second year of teaching the subject, which he calls "How to Pay Attention." But instead of giving clues about how to focus (which could be suggested), he tells students about attention as a cultural phenomenon. Dr. Siver says that they are discussing "how people talk about attention," and the course includes topics such as "economics of attention" and "attention and politics."

Part of the homework for the “economic” week was an analysis of how an application or website “grabs attention” and benefits from it.

Student Morgan Griffiths has chosen YouTube.

“Many of the media I consume are about RuPaul's Drag Race television show,” says Griffiths. - At the end of many videos, RuPol itself appears and says: “Hey, friends, when the video ends, just open the following, this is called a telezapa, but go ahead, I advise you.”

Her classmate Jake Rochford, who chose the Tinder application, noticed a strong obsession with the new “super-like” button.

"When the super-like appeared, I noticed that all functions work as ways for me to keep the app open - instead of helping me find love," Rochford says.

After Jake completed this task, he deleted your account.

However, Professor Siver is not at all luddit.

“Excess information always seems new, but in reality this phenomenon is very old,” he says. - For example: "There is a 16th century courtyard, and there are so many books." Or: "We live in late antiquity, and there are so many scriptures."

“It cannot be that there are too many things to pay attention to. This is not logical, - says Siver. “But it may be that there are things that are actively trying to grab your attention.”

It is necessary to think not only about the attention we spend, but also about the one we receive.

Sherry Turkle, a sociologist and psychologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, has been writing about our relationship with technology for several decades. She claims that the devices that follow us everywhere have led to a new trend: instead of competing with their siblings for the attention of their parents, children are now competing with iPhones and iPads, Siri and Alexa, Apple watches and computer screens.

Every moment they spend with their parents, they also spend along with the need of the parents to be constantly in touch. Turkle in his latest book, Restore Conversation, describes in detail the first generation exposed to this impact. Now this generation is from 14 to 21 years old.

“There was a generation that had a very unsatisfactory youth, and which in fact does not associate phones with any glamor, but rather with a sense of deprivation,” she says.

At the same time, Turkle is cautiously optimistic:

“We are starting to notice that people are gradually moving towards“ having a good time. ” Apple is slowly moving to plead guilty. And culture itself is moving towards recognizing that this cannot continue. ”