The course of lectures "Startup". Peter Thiel. Stanford 2012. Lesson 16

- Transfer

- Tutorial

In the spring of 2012, Peter Thiel , one of the founders of PayPal and the first investor in FaceBook, taught a Startup course at Stanford. Before starting, Thiel said: “If I do my job correctly, this will be the last subject that you will have to study.”

One of the students of the lecture recorded and posted the transcript . In this habratopika degorov , translates the sixteenth lesson, astropilot editor .

Lesson 1: Challenging the Future

Lesson 2: Again, Like in 1999?

Lesson 3: Value Systems

Lesson 4: Last Step Advantage

Lesson 5: Mafia Mechanics

Lesson 6: Thiel Law

Lesson 7: Follow the Money

Lesson 8: Presenting an Idea (Pitch)

Lesson 9: Everything Is Ready, But Will They Come?

Session 10: After Web 2.0

Session 11: Secrets

Session 12: War and Peace

Session 13: You Are Not a Lottery Ticket

Session 14: Ecology as a Worldview

Session 15: Back to the Future

Session 16: Understanding Yourself

Session 17: Deep Thoughts

Session 18: Founder - Victim or God.

Occupation 19: Stagnation or Singularity?

Lecture 17 - Understanding Yourself

Three guests joined the discussion after Peter's lecture:

1. Brian Slingerland. Co- Founder , President and CEO of Stem CentRx;

2. Balaji S. Srinivasan, CTO of Counsyl; and

3. Brian Frezza, co-founder of Emerald Therapeutics

I. The Longevity Project

How many years longer can people really live? This question is still open. Perhaps it will be extremely difficult to answer. But, there is a feeling that biotechnology is well placed to try to do this. The biotechnologies developing as a result of the computer revolution look very exciting if we think about the fact that a whole range of problems - cancer, aging, death - are close to their solution.

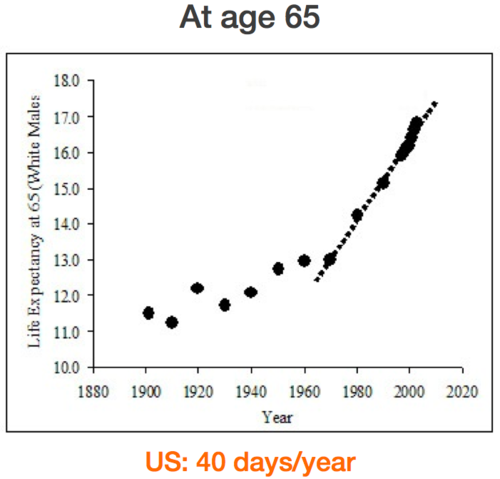

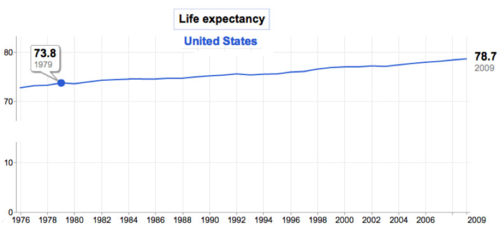

Even without the biotechnological revolution, life expectancy has increased significantly. Growth was around 2.5% decade after decade. From the middle to the end of the XIX century, life expectancy increased by 2.3 - 2.5 years every decade. If you build a graph on the points corresponding to the maximum life expectancy for each country (as a rule, we will talk about the life expectancy of women), then together you will see a straight line. This is not entirely consistent with Moore’s law, but is quite similar to it. In 1840, life expectancy was only 45-46 years. In the past century and a half, the problem of prolonging life has been exponentially more complex.

To some extent, the United States is a little behind in this matter. Life expectancy here is a couple of years below the global maximum. There are various reasons: Americans eat poor food, Americans are not physically active enough, etc. But, although the United States is lagging behind, the trend remains the same - life expectancy is constantly growing.

You can look at this question in a different way: each additional day spent adds 5-6 hours to your future life. This is a startling conclusion! The question is what will happen next. Will the straight line on the chart remain straight? Will the process slow down? Will it accelerate? Until 1840, growth in life expectancy was almost linear. Only recently has he really accelerated dramatically. Maybe this is a short surge that will end soon or is this just the very beginning of a sharp acceleration? All this remains to be seen.

II. Luck, life and death

A. Death as bad luck

In a sense, longevity is the opposite of bad luck. In a global sense, when you are out of luck, you are in trouble. Think about everything that could go wrong. Perhaps part of your DNA mutates and cancer begins to develop. You may be hit by a car. Maybe an asteroid will fall on you. A lot of things may not be lucky. Thus, the question of prolonging life can be asked in the form - which of these troubles and to what extent can be overcome.

From the 17th to the middle of the 19th century, the prevailing opinion was that we could deal with any of these troubles. Francis Bacon's New Atlantis was a classic vision of accident-free utopia. It was New Atlantis, because, unlike the old, destroyed by the gods, in New Atlantis the Atlanteans had complete power over nature.

This point of view began to lose ground around 1850. Luck and uncertainty are becoming increasingly dominant concepts as a basis for thinking about the future. This shift was probably due to the development of actuarial calculations and life insurance. When people started working with data, it became clear that life and death can be reduced to probability functions. The likelihood that a 30-year-old will die in the same year is 1 in 1000, while for a 100-year-old, this probability is already 50%.

If we work a little with this math, it will become clear that the solution to the eternal life problem is to solve a simple equation:

- the probability of dying in the year x

- the probability of not dying in the year x

- the probability of surviving to the end of the year n

- the probability of living forever

- the mortality equation

Unlimited probabilistic thinking can be dangerous. It kills a person’s ability to shape the future. The film "The Old Men Are Not Here " describes this moment well: one day you will stop being taken and they will shoot you at a grocery store in Texas. If everything is just an accident, you have no choice but to come to terms with fate. However, this approach does not take into account your ability to think and decide whether to get involved in a game in which too much depends on luck.

A small historical footnote: In 1700, the assertion that people can live forever seemed more realistic than today simply because there were people who claimed to be 150 years old. Since there was practically no accounting at that time, good “marketers” could convince other people that they were of an extremely honorable age. Today it is quite easy to understand the motives of these people. If you are a 70-year-old man in London at the beginning of the 18th century, then you will be perceived as the next unfortunate and will not be provided with special assistance. However, if you are 150, then this changes everything, and you can even count on retirement from the King himself.

B. Transition to certainty

Can we move biology from the world of statistical and probabilistic approaches to something more definite and decidable?

It depends on many factors.

You can think of death as an accident. There are various types of accidents. You can decompose them into a spectrum - from microscopic (such as genetic mutations) to macroscopic (accident) and cosmic scale events (asteroid fall).

To finally solve the problem of aging, you must get rid of all these troubles. But there is a feeling that certain macro- and space incidents in any case are and will remain random events. However, the solution to these problems can be postponed - even if we can deal with microscopic incidents - the life expectancy can already be increased to 600-1000 years.

III. Computer Science and Biology

A. Difficulty of the task

Like death itself, the process of finding new drugs is largely dependent on luck. Scientists begin by analyzing approximately 10,000 different compounds. After a lengthy selection process, out of these 10,000, about 5 remain, which are admitted to the third phase of testing. Maybe one of these 5 drugs will be tested and approved by the FDA.. This is a rather long and largely random process. That is why the launch of a biotechnology company is extremely risky. Most of them exist for 10-15 years. During this period, you have virtually no control over the process. What seems promising may not work at all in the end. There are no iterations, nor a feeling of approaching the goal. There is only a binary result (“yes” or “no”) at the end of a largely random process. You can work hard for 10 years and not know until the very end whether you have wasted time.

In Internet businesses, the basic rule is that a company is successful if each subsequent round of financing is more successful than the previous one. In biotechnology, this is almost impossible. Investors get tired. Nothing works. Some investors openly declare that they do not care about valuation, since everything will go to them anyway, even if in the next round capital will be diluted with a decrease in the value of the shares or their additional issue. What is the point of discussing an assessment if it all depends on luck?

In fairness, we must admit that all the processes focused on luck and statistics, which dominated the thinking of people, have worked quite well in the past few decades. But this does not mean that it makes sense to continue to focus on randomness. The cost of discoveries obtained by such methods can grow very quickly. Perhaps we have already found everything that is easy to find. If this is so, then it will be difficult for us to develop without anything on hand, but random processes. This will be reflected in research costs. In 1975, the cost of developing a new drug was $ 100 million. Now it is 1.3 billion. Probably all the funds that invested in biotechnology lost money. Investing in biotechnology was just as unwise as investing in green technologies.

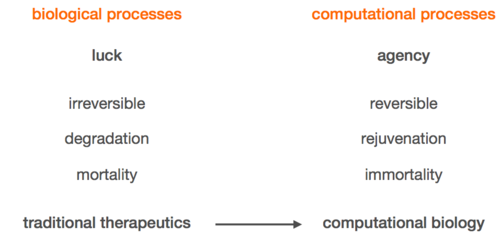

B. The future of biotechnology

Drug development is essentially a search task, and the search area is extremely large. There are a huge number of possible connections. An important question is whether we can use computer technology to reduce the impact of the case. Can computer science make biotechnology more deterministic? At the most basic level, biological processes can be seen as attracting a quantum of luck to the process of irreversible degradation. Traditional therapy largely reflects these processes. In contrast, computational processes are reversible. You can learn and reprogram processes as needed. The main question is to what extent biological tasks can be reduced to computational ones.

| Biological processes | Computing Processes |

| luck | organized processes |

| irreversible | reversible |

| degradation | rejuvenation |

| mortality | immortality |

| traditional therapy | computational biology |

The cost of determining the primary structure of DNA micromolecules is rapidly decreasing. In 2000, it was worth $ 500 million. Today it can be done for 5 thousand. In a year or two, it will probably cost $ 1,000. The question is whether we can really do with the information received all that we assumed.

“This discovery will lead to revolutionary improvements in the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of most, if not all human diseases.”

Bill Clinton, 2000

The Human Genome project was seen as incredibly revolutionary in the late 90s. But his result did not match all the hype created around. Perhaps the project appeared too early or was too expensive. But another reason for failure may be that decoding the genome itself is not a problem at all. The main problem may be that we simply don’t know what to do with the received data. The question of exactly which part of biology problems can be reduced to computational problems is still open.

IV. Examples

We will highlight some questions and then discuss them with representatives of three companies that deal with extremely interesting issues in biotechnology: Stem CentRx, Counsyl and Emerald Therapeutics.

Of these three companies, Stem CentRx is closest to traditional biotechnology. But, nevertheless, a significant part of their tasks is computational. Their main goal is to cure all types of cancer. They claim that cancerous tumors contain stem cells that are significantly different from the underlying tumor cells. It is this type of cell that controls the development of the disease and tumor. Thus, they try to influence stem cells and thereby defeat cancer.

When viewed from the side, the problem is that chemotherapy can be extremely ineffective in treating cancer. It is very difficult to calculate the required dose. Too low doses are ineffective. Too high kills the patient along with the disease. So if you can isolate a subset of the cells that are responsible for growth and act directly on them, chemotherapy can be made much less destructive and significantly more effective. So far, research on Stem CentRx in mice has been very promising. We must find out if this approach works for a person over the next year or two.

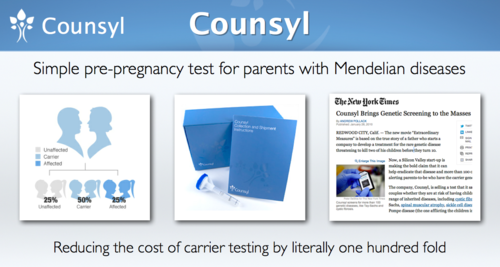

Counsyl is a company that works in the field of bioinformatics. Their goal is to capture the pregnant genetic screening market. They developed one simple test for approximately 100 genes that can be tested to determine if hereditary diseases are present. They focus only on diseases inherited by Mendel’s laws , since it’s still too difficult to determine how more complex genetic combinations work. In this way, Counsyl defined a real and very clear set of tasks. Counsyl is currently screening around 2% of newborns in the United States and expects this number to increase significantly in the coming years.

Emerald Therapeutics uses calculations more than any of the other companies represented. Their main goal is to cure all viral infections by reprogramming cells, that is, turning cells into programmable machines. The idea is to build a molecular machine that will tag cells containing viruses, and then command these cells to self-destruct. At the moment, the work of Emerald is classified and we can not tell more. However, the high level of paranoia in companies working in the field of programmed antiviral therapy is explainable. They work with great secrets that will be relevant for a long time, unlike, for example, web applications that have 6 weeks to take over the world.

So, let's talk with Brian Slingerland from Stem CentRx, Balaji Srinivasan from Counsyl and Brian Frezza from Emerald Therapeutics.

V. Prospects

Peter Thiel : Mark Andreessen attended our classes a few weeks ago. He said that on the Internet in the late 90s, many ideas were essentially correct, but their time had not yet come. Even if you agree that the next phase in biotechnology is an increase in the use of computing, how can you know that now is the right time? How do you know that you are starting your first steps not too early?

Balaji Srinivasan: Genome decryption is similar to the first packets sent via ARPANET. This is proof of concept. The technology already exists, but for people it is still not convincing. Thus, the creation of something that really works leads to the emergence of a huge market in which people can really come and get the created genome. Just like with email and word processors. Initially, these things were uncomfortable. But when it became possible to clearly demonstrate their benefits, people left their comfort zone and accepted them. Testing pregnant is one of the key areas. People find it important to make sure their children are as healthy as possible. And then, probably, with the obtained data it will be possible to do many more positive things.

Peter Thiel: So the question is, how can you help people overcome the common fear of the genome decryption procedure? And the answer: “Do it for the children?”

Balaji Srinivasan : Yes. No one will spend $ 1,000 to buy a computer just to sit on Twitter. But when you already have a computer, you don’t need to spend extra money to start using Twitter. Thus, solving the problem of initial implementation is the first step. Empirically, we are already starting to see a very confident adoption of this technology. Thus, we are confident that we can solve the problem of implementation.

Peter Thiel: Talking about the cancer issue is exciting, but also disturbing at the same time. This is an old problem. Nixon said in 1970 that by 1976 we would win the war on cancer. People have been working on this for 40 years. And although we are now 40 years closer to the solution, it still seems to be further than ever. Does the fact that the solution to this problem has already taken so long does not mean that this problem is incredibly complex and will not be solved in the near future?

Brian Slingerland: People in general have been following the same path for the past 40 years. The usual approach to cancer treatment is “carpet bombing” chemotherapy or the like. All the approaches that were used earlier, in fact, are surprisingly similar. We decided to take a completely different path. 40 years of failure taught us something important. Previously, the main metric of therapeutic efficacy was the reduction in tumor size. However, this metric is not the best - tumors can shrink and then grow back. Focusing on reducing the size of the tumor can lead to effects on the wrong cells. Using bioinformatics helps us see better approaches. Thus, we do not agree that the problem will not be resolved in the foreseeable future; we firmly believe that we have a good chance to do just that.

Brian Frezza : There is already an answer to half of the question - we definitely have not been late, since viruses still exist. Are we too early? I do not think so. The layman's view of healthcare is quite different from reality. Industry players are paranoid in securing their secrets right up to the time the product launches. People underestimate this moment and pay attention only to what exactly and when it is introduced to the market. What people see at this particular moment began to be developed over the decades of how they began to think about it.

In the late 70s and early 80s, with new DNA recombination technologies and the development of molecular biology, biotechnology received a significant surge. Genentech led from the late 70s to the early 80s. 9 of the 10 largest US biotechnology companies were created in this short period of time. Their technology came out 7-8 years later. And it was a window: after that, not many new integrated biotechnology companies appeared. There was certain material that needed to be found. People found him. Prior to Genentech, the focus was on pharmacology, not biotechnology. This window (turning into an integrated pharmaceutical company) was closed for about 30 years before the advent of Genentech.

Thus, we bet that while the window for traditional biotechnology companies is closing, the window for computer biotechnology has just begun to open. Anyone who crawls through this window will be able to gain a foothold. There are huge monopolistic barriers to entry into the market. Here, the one who makes the first move often becomes the one who takes advantage of the last move. Imagine that IE or Chrome would have to go through clinical trials just to get to the market. It would be much more difficult to enter the game. Thus, one who can develop good technology and bring it to the market first will have an advantage.

Peter Thiel : Let's talk about your corporate strategy. Even if your technology works, how do you plan to spread it?

Balaji Srinivasan : If you think about drugs, biotechnology, and now genomics, are, in fact, different entities, then you will understand that companies working with genomics can work in a completely different way. Genomics is much more computationally sensitive than pharmacology or traditional biotechnology. In molecular diagnostics, but not in traditional therapy - if you examined samples, then you are on a superhighway. Internet rules apply. You can go from concept to product and sales in 15-18 months. This is not as fast as with online businesses. But it is much faster than the 7-8 years that are required in traditional biotechnology. In the early 90s, a window was opened for Web 1.0. In the late 90s there was a window for Web 2.0. Now the turn of genomics. We think that the task of biology is sensors and data collection. Everything else should be done on the command line.

Brian Slingerland : Stem CentRx relies more on traditional biotechnological processes. We spent 3 years at the stage of developing evidence of the correctness of the concept. Now that we have completed all studies of the effectiveness of the treatment of cancer in mice, we are fully in the mode of drug development. This process can be accelerated by borrowing best practices from a technical culture.

Brian Frezza: We create a platform, not an isolated product. We are creating the infrastructure for all kinds of future antiviral technologies. Thus, the key point is the ability to keep the science in check - in addition to pure creativity, both routine and scaling should take place. Culture is also an important aspect. Although we have PhDs in organic chemistry and molecular biology, we still focus on the established culture of technical startups. We automate processes in the laboratory using advanced robotics. We use git to track changes in work records. We write tons of code. We are pioneers in our field and we try to move very quickly, but we are also building a platform designed for exponential growth.

Peter Thiel: Where is the confidence that no one else secretly uses the same strategy? And if you know what other people do or don’t do, why do you think that they don’t know the same thing about you and that your secrets work.

Balaji Srinivasan : It's like a joke of Donald Rumsfeld: There are known unknowns. In general, we think that most people miss key secrets in the healthcare industry because they are too immersed in the current situation and cannot think about finding ways to better solutions. Compare health and fitness. Fitness is your area of responsibility. You can enroll in a good gym or find a personal trainer. Both options are good. But the choice is yours only - you must take the initiative. Now imagine if you had a similar choice in health matters. You come to a meeting with a doctor and start telling him about your research, and the doctor precipitates. You either undermine their authority or you are an idiot. But, strangely, you stay with your body for life, and the doctors with you only about 20 minutes a year. As a result, fitness is one of the few areas in medicine,

When these systems are built, it will be very difficult to immediately get rid of prejudice.

People will understand that they simply did not think about unconventional approaches. Truly working things will seem insane.

Brian Frezza: One of the unpleasant consequences of the biotechnology boom is what happened to patents. In pharmacology, traditionally the objects of protection were the compositions of drugs. In biotechnology, it has become possible to patent generic approaches. Genentech, for example, succeeded in patenting recombinant antibodies as a general concept. Thus, biotechnology is teeming with similar highly generalized patents. Some biotech companies literally earn millions just by selling licenses; they don’t produce medicine at all. So it’s better not to heat up the public interest in the new technologies you are developing, so as not to provoke patent trolls.

Ultimately, you cannot prove otherwise. It is possible that there is a company called Ruby Therapeutics, which is working on the same thing as us. But we strongly doubt it, given that we are working on unique things. Even if you know that competitors exist, it’s still better for both companies to remain silent until they can begin to make a profit.

Brian Slingerland: In fact, no one seeks to reveal their secrets. Our area is very different from the fast-moving industry of online startups. Here, if you have something unique, you must first nurture it. It’s good practice not to release press releases until the drug is released to the market. Thus, the whole point is in balance. Since our approach has proved its worth, and we are moving on to human trials, we have become more public. No one wants to take a drug developed by an unknown company that has no information on the site. You just need to make sure that you are not disclosing information too soon.

Of course, you need to understand that 10 companies are following you. It is reasonable to assume that you must work better and faster in order to get ahead.

Peter Thiel: If you know that Ruby Therapeutics or 10 of its other variations do exist, would it not be wise to be more open and collaborate? And how do you recruit people if you are so closed?

Balaji Srinivasan : In ecology, when you want to know how many species live in the jungle, you make a cut and then zoom in. Estimating demand is a similar task. If you carefully study your network of contacts — you’ll explore that part of the jungle located in Silicon Valley — and you don’t see raising capital and people working on the same problems, you can be quite sure that you are alone. People really have to come from nowhere.

Personal connections are very important for recruiting. We try to receive and receive from each engineer a link to two people. 2 ^ n is a very good scaling. You get great people, but also have to stay out of sight.

Peter Thiel : This hiring strategy has worked well in all the companies in which I have been involved. But you must be careful with her. If you ask a person with an MBA degree to give you contacts of talented people who work well, you will get too many candidates. However, if you ask the engineers the same question - and maybe you even want to hire their friends directly - you can only get silence in response, because they are too shy. So you have to find a way to make them comfortable recommending people.

Brian Frezza : One strategy that really works is to sit next to your engineers and go over their Facebook friends lists, asking them to name people who are good experts and which one they would like to work with.

Peter Thiel : There is a prejudice that entrepreneurs in the Silicon Valley should engage in web or mobile applications. Why should people instead think more about working in biotechnology and computing?

Balaji Srinivasan : It must be remembered that the next promising area will not look like the previous one. Search technologies did not look like a desktop, and social networks did not look like search engines.

The human genome will never become obsolete. Mobile technology, desktop, social networks? Hard to tell. Mobile technology seems to be expecting great growth. So betting on them is at least reasonable. Desktop software? He no longer has real advantages. But social networks are already occupied and most of the territories there are already divided.

Ultimately, you should just be worried about what you are working on. Another dating app doesn't really bother anyone. It is difficult to imagine that someone would cheer for him, sweat and cry. Significance is an important argument for trying to think differently. And we believe that genomics is a really significant area.

Brian Frezza: Elon Musk is a recruiting master. His approach is sharp and simple: “We do not pay as well as Google pays. But our project will be the most exciting in your life. ” You want to interest people who find this approach attractive. People always see a startup as a lottery. But the satisfaction of starting the technical revolution is much more than just stamping money.

Brian Slingerland: One of the reasons people from IT can ignore biotechnology is because they think they will be given a secondary role. However, this is far from the case in many biotechnological companies. IT people are at the epicenter of what we do at Stem CentRx. So if IT people are interested in finding a cure for cancer or the like, they really need to think about this area. I did not forget to say that we have open vacancies?

Peter Thiel : We usually say that advertising works best if it is hidden. But sometimes it really works if it is completely transparent. [laughs]

Opacity can be very tiring. Well-known wisdom in the world of venture capital says: “If you need money, seek advice. If you need advice, ask for money. ” And this game is tiring. Sometimes I really want to hear: "In fact, I only need money."

Question from the audience : [inaudible]

Peter Thiel: It is not normal that the FDA is a bottleneck in global drug development. There must come a turning point, after which the United States will no longer dictate to the world which drugs to develop. After crossing this point, the United States will have to compete with China in the speed of drug development. This could be a huge paradigm shift. So, although things don't look so good right now, the future may be promising. The activities of SpaceX in the initial stages were heavily regulated, but they survived and went through it. Aviation regulations have also been made much easier recently. So an unfriendly attitude in the initial stages can develop into great opportunities.

Question from the audience: When you reveal your secrets to future employees, do they try to use this knowledge to blackmail you and agree on a bigger salary?

Brian Frezza : We had no such problems at all. Venture capitalists do not sign non-disclosure acts, but candidates do so. In addition, they will have to work for several years to repeat the technology on their own.

Question from the audience: What role does HIPAA play in technological innovation?

Balaji Srinivasan : HIPAA can be seen as a technical challenge. How can we follow different standards, etc.

But it is also an interesting challenge for genomics. The human genome contains a wealth of information about his relatives. On the one hand, these data are classified medical information. On the other hand, they, in fact, are statistical and can be useful only after aggregation. Thus, the challenge is to find out how aggregation can be performed without revealing data. To benefit from your genome, you simply must allow some calculations to be made on it. The task is to accelerate the shift in public consciousness towards the acceptability of this processing, while at the same time maintaining strict secrecy of personal data.

Question from the audience: Unlike the Network, where you can get feedback in a few minutes, how can you know that you are on the right track in computational biotechnology?

Brian Frezza : We use physical models and experiments to test. We use not only statistical approaches. But all processes are internal. We do not seek external verification. Just like Instagram does not call people from the street to evaluate their program code. You develop a plan and follow it within the company. Sometimes a cycle of several years is required to obtain results. And you work as efficiently as possible to shorten the duration of this cycle.

Balaji Srinivasan: Slow iterations are not an immutable law of nature. Pharmaceutical and biotechnology usually develop very slowly, but sometimes development is very fast. Work on insulin in the years 1920-1923 went at a rate characteristic of software development. Today platforms like Heroku have significantly reduced the iteration time. The question is whether we can do this with biotechnology. Nowhere is the statement that you cannot go from concept to the counter in 18 months carved in stone.

Brian Frezza: It depends a lot on what you are working on. Genentech was founded in the same year Apple was founded in 1976. It takes time to create a platform and infrastructure. There will be a lot of overhead. Auxiliary things may take longer than the entire life cycle of the finished product.

Question from the audience : Compare the venture capitalists from the world of biotechnology with the “classic” ones.

Brian Slingerland: We never followed the path of classic venture capital, because this approach does not work in relation to biotechnology. All venture capitalists who invested in biotechnology have lost them. They usually consider time frames that are too short. Venture capitalists who say they want to work with biotechnology usually want the product to enter the market as quickly as possible.

Brian Frezza: “An integrated drug platform” is a threatening phrase for venture capitalists. Most VCs focus on globalization, rather than real technical innovation. VCs usually find a company with one drug and then pour a ton of money into it to push it through a costly test process. Most VCs are not interested in companies that have several drugs and that are conducting serious preclinical studies.

Question from the audience: How useful are cancer test data from terminally ill patients? Is this data inaccurate or not at all indicative?

Brian Slingerland: Lack of testing in the early stages of the disease has always been a problem. However, our technology is being developed taking into account the possibility of its application at different stages of the development of the disease in patients. All I can say is that our approach is not technically tied to the stage of the disease. But in general, your question is fair. That is why traditional drugs that show progress at the beginning often fail in extended trials.

Question from the audience: What were your first tasks or problems?

Brian Frezza: The period of the creation of the laboratory turned out to be unrealistically long. 100% of our time was spent on equipment purchase, price negotiations, startup problems, etc. We greatly underestimated the time required to get to work, because we came from ready-made, well-equipped laboratories. Usually, the process of preparing for work takes a year. Here we see a huge difference compared to the world of the Internet and computers.

Peter Thiel: In an online business, you can get started right away. At PayPal, the biggest problem was that, by order of Max, employees had to collect their own desks. But Luke Nosek thought even that was superfluous. So he found the company Delegate Everything, which sent him the jack of all trades, which is usually called by older women, who gathered him a table, and he could spend more time working at a computer.

Balaji Srinivasan: Startups are always hard at the beginning. The offices have mattresses and ironing boards. You have to rush to clean the meeting room. But the most difficult thing is to determine whether you are really doing the right thing and whether you plan to create something meaningful. You are not required to have a science-based project at the start. However, you must do some analytical work and make sure your approach is viable. You must give yourself the best chance of success when additional opportunities open up in the future.

Note :

I ask for translation errors and spelling in PM. Translated degorov , editor AstroPilot , all thanks to them.