Who invented double-entry bookkeeping?

Used in accounting, including modern accounting, double entry is one of the oldest information technologies. Meanwhile, who invented it is completely unknown. I have my own hypothesis on this score. It was published several years ago, but the circulation of the book is insignificant - I don’t think that at least a dozen Habrachians got acquainted with it. The rest aren't you curious?

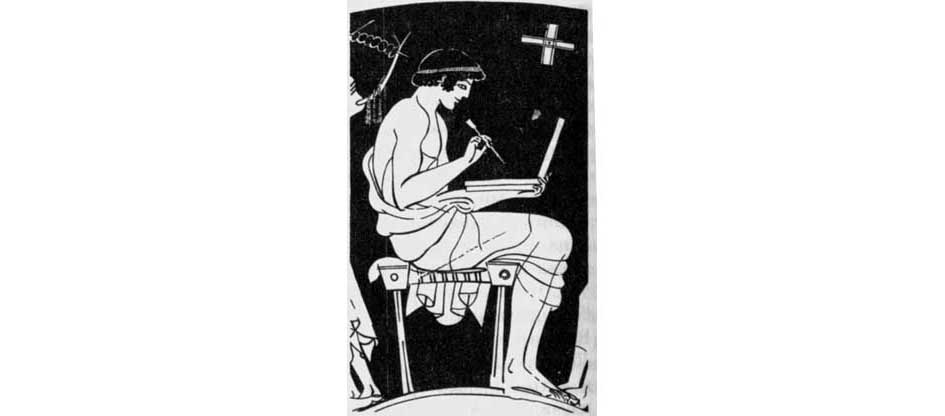

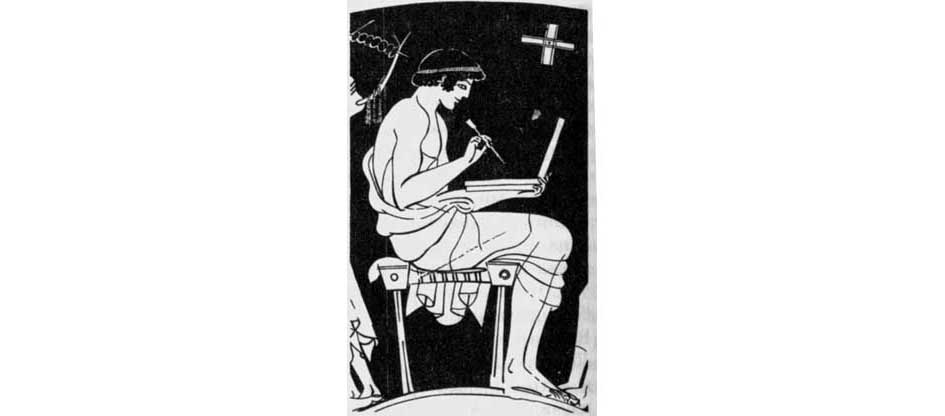

To give the post due intrigue, I’ll inform you that the growth of young and talented ancient Roman IT specialists had a hand in the invention of double-entry bookkeeping. The image of one of them, behind the laptop of the antediluvian model, is attached.

Okay, I joked about the ancient Roman programmer. What is it ancient Roman, when ancient Greek? However, about double-entry bookkeeping - no jokes. So many people cry with burning tears from her that her tongue doesn’t turn around.

For those lucky ones who are far from double-entry bookkeeping, I explain the situation.

The founder of double-entry bookkeeping is considered Luca Pacioli, who published in 1494 the first accounting work entitled “Treatise on Accounts and Records”. The monk-mathematician did not work as an accountant for a day and had a very distant relation to accounting, which is very noticeable from the treatise, which is simply boring to read, how boring it is to read most modern accounting textbooks. This alone indicates that Pacioli was not the author of the methodology, but an elementary compiler (which at that time was not considered shameful).

Most accounting historians are inclined to believe that the real inventor remained unknown: for example, some medieval merchant or the entire merchant family, who for decades or even centuries kept the technology secret from competitors. Or even not a medieval family, but more ancient - the ancient Roman, for example.

I will say right away that I am also inclined to the ancient Roman version. However, one must understand what the main difficulty is. The difficulty is not in obtaining any written evidence of the invention of double-recording - there probably isn’t any such - but in understanding why double-recording was invented.

The purpose of double recording is the most mysterious in the history of its invention!

Double-recording itself is a pretty solid and tightly knocked-down technology. It has a set of well-known advantages and a set of equally well-known disadvantages, but the fact that double recording is a technology cannot be denied.

But - any technology is intended for something, and double-recording is as if it was not intended for anything: the technology itself is like an alien. Imagine a device that has fallen from the sky: some wires, sensors, terminals and connectors, and it’s even more or less clear how it works ... and you’ll tear apart the mission as a whole. So with double recording the same story.

Her device is quite tricky, but if in a nutshell, it looks like this. There are two unequal values: A (asset) and P (passive). If you subtract P from A, you get the difference, it goes without saying. We call the difference K (capital).

We take the formula (the so-called balance equation):

A - P = K

Move P to the right side, we get:

A = K + P

Just look how cool it turned out!

Now, if we begin to register the values of A and P (which is the purpose of accounting), but along with them we also begin to register (not calculate how it begs, namely register!) The difference between them K (capital), then a double record with its debit and credit, and their total posting amount. A debit loan combined in one accounting entry is an addition to equal amounts of equal values, the same with deduction. What happens in this case? The same values will turn out, what else can happen ?!

Such simple arithmetic for the first grade, but why was it - this same accounting balancing - was invented and put into practice, what’s the question?

They explain it in different ways, but each time it is unconvincing: either for checking books, or for calculating capital, or in connection with the appearance of joint-stock companies. The reasons, from my point of view, are all unconvincing. In Russia, they learned about double-entry at the end of the 18th century, another half a century was required for double-entry to be put into practice, but even then the Russians kept their books: regulations were issued, statements were filled out, and property was recounted. Bookkeeping was, but imagine, there was no double entry!

So I put forward my own hypothesis explaining why it was necessary to register K (capital) together with A (assets) and P (liabilities).

According to my version, double recording was invented in Ancient Rome, in connection with the qualifications (here I am not original).

Cens - a census conducted once every 5 years. The qualification itself was as follows. Each legally independent citizen swore an oath about himself: his full name, place of birth, name of his father or (for freed slaves) former owner, age and property subject to tax. On the basis of property owned by the Roman, he was assigned one or another qualification category, and in general - his rights and privileges were determined.

Well, great, but what does double-entry accounting have to do with it? But with it.

In the directories it is written that the censors, who were elected from among the consuls (former consuls), were responsible for conducting qualifications in ancient Rome. The censors had the right to reduce the number of civil rights that the Roman enjoyed according to the results of the qualification, and even had the right to remove the senator from the Senate. At the same time, according to the directories, not only purely political and administrative considerations were taken into account, but also the personal life of each citizen, that is, the censors took on the role of guardians of morality.

Well, how did you get an official with such broad powers? I could not establish whether the censors had the right to belittle the Romans in civil rights only during or between the qualifications, that is, on an ongoing basis, but strongly suspect that they had. Otherwise, how could statesmen observe the morality of fellow citizens if qualifications were passed once every five years? The status of an official with such meaningful functions as the censor should have been constantly maintained, therefore, the authority of the censor was required to include an ongoing audit of the censorship lists.

Justified Assumption? It seems reasonable to me.

Then figure out how the censors could revise the lists of Roman citizens in between censuses. The essence of the audit, for any of its national features and legal formalities, could be reduced to one thing: a censor was declared to a Roman citizen in order to check his property status - we will not forget that an audit of the censorship lists of Roman citizens involved first of all a check of property status, and then the rest . Based on the results of the property check and the observations accompanying it, the censor determined: is the behavior of this Roman citizen moral? should not this belittle the rights of a Roman? Is he worthy of belonging to a well-known social stratum?

If I'm right, it becomes clear that whip, which the ancient Romans were forced to keep a home written record: censors.

We conclude that each law-abiding Roman, for fear of visiting the censor, kept a record of household property. This does not explain the invention of double-entry, but brings it closer, especially if you find out what kind of written records the ancient Romans could keep at the time of the qualification.

The main thing is not even what, the main thing is on which medium.

In ancient Rome, according to modern reference books, the following information carriers were used: papyrus, wooden planks, parchment, tree bark, clay shards, plaster. On which of the information media did the venerable fathers of the Roman families keep home records, and in what incomprehensible way did the media use associated with the invention of double-entry?

What medium did the ancient Romans use for writing records of household property?

We bark the tree bark, clay shards and plaster immediately: it is simply difficult to imagine.

I suppose that the papyrus was not used by the Romans to run accounts for the reason that it was a little expensive after all. Throughout the ancient period, papyrus was the main writing material for the Mediterranean countries, but only when performing certain types of writing: for example, literary texts on papyrus scrolls were written and legal contracts were drawn up, but daily business records were not, for reasons of economy. Otherwise, household papyri would be preserved in mass quantities, but they did not survive: it means that it simply did not exist.

Then parchment codes, which, as an information medium, are much more durable and attractive than papyrus scrolls? It is also unlikely. Parchment was more expensive than papyrus - cattle skin after all! - Therefore, its use in home accounting looks even less likely. Secondly, the use of parchment does not go according to chronology.

To understand the sequence of events, I compiled the following chronology. Estimate yourself what and when, according to official reference data, what happened.

3 thousand BC - the first surviving papyrus;

578-534 years. BC. - the establishment of qualifications, initially property;

mid 5th century BC. - the value of qualifications has increased significantly;

443 BC - introduced the position of censor;

312 BC - conducting the first cash qualification;

OK. 180 BC - start of parchment production;

mid 1 century BC. - the censor position is liquidated;

74 A.D. - cancellation of qualifications;

1 century AD - the existence of codes has been reliably attested;

2 c. AD - the invention of paper;

4-5 centuries AD - the scroll began to be supplanted by the code;

8 c. AD - paper penetration in Europe.

11 century AD - cessation of the use of papyrus as writing material.

Parchment began to be produced a hundred-odd years after the first cash qualification and two and a half centuries before their cancellation. While parchment production was established, which was unlikely to happen quickly, censorship began to decline ... and taking into account the high cost of parchment ... and the fact that parchment codes appeared during the abolition of censorship ... It is very doubtful that the ancient Romans who lived in the age of censorship used to conduct home accounting parchment.

If historians do not lie, and home accounting in ancient Rome, carried out during the time of qualifications, was nevertheless written, it remains to be assumed that it was carried out on diptychs — two-part writing boards covered with a layer of wax: the letter on them could be scratched with a stylus and then erased. (The drawing on the ancient Greek vase does not depict a laptop, but a diptych writing instrument ... you guessed it, of course).

How many diptychs were required to record the property of one family? Let's figure it out. If we assume that no more than forty lines could be written on one diptych (twenty on one board and twenty on another - what do you think fit better? Is it a sharp stick on the waxed surface?), And the total number of records was, let’s put , a thousand (household utensils, pets, slaves, etc.), it turns out twenty-five diptychs ... the size of a laptop. How do you like compact home accounting, not the largest family, on twenty-five laptops?

In favor of the assumption that home accounting was conducted in diptychs, historians friendly mention of a special counting room ( tablinum ) for storing home accounting documents. Term tablinum- “archive” is an etymologically related tabula - “board, plate, table”, and tabella - “board, plank”. So what information media were kept by the ancient Romans in tablinum ? Is it papyrus or parchment?

And the most important.

During the qualification, the Roman swore oath of magnitude (total value balance), but not of property turnover. It does not follow from the definition of qualifications in handbooks that ancient Roman law obliged citizens to keep receipts and expenditures ... and where is the evidence that the ancient Romans really kept it, as most historians unreasonably assume?

The difference between profit and loss accounting and accounting for balances (balances), I hope, is clear: in the first case, it records how much property has left the farm and how much has arrived (income / loss), and in the second case, only cash property balances as of the current date are recorded. For balance accounting, the ability to add new ones over old records was very useful and desirable. For daily rough accounting, something inexpensive and non-expendable was needed, and a simple waxed board was, without a doubt, accessible and common material, and it did not need to be thrown away when updating the record.

This is where everything converges into one dense logical point: the fact of conducting home accounting is rather unusual for today; balance accounting, which the Romans were able to carry out on the media available to them; the multiplicity of information carriers required for accounting; censors who had the right, on the pretext of a censorship check, to invade Roman dwelling; and the subject of our consideration is a double entry.

What do you think, would a high official, who has applied to a Roman house to revise his property status, recount the accounting records captured in dozens, and possibly hundreds of diptychs? No normal official, including the ancient Roman, would not agree to such a mockery from his point of view. How do you imagine the dialogue between the censor and the censored Roman?

"Hello, I am a censor, I need the total value of your property."

"Twenty minutes."

“How can you confirm it?”

“And there’s ninety diptychs in my tablinum. If you want, recount. ”

No, the censor would require first to familiarize himself with the general figure of the current property status, then, in case of doubt about the authenticity of the credentials, proceed to a detailed check. To wait until the revised owner of the family summarizes a thousand or more digits, the censor would also not agree, wishing that the final figure be presented to him immediately.

From where did the Roman subject to censorship, at the first request of the censor, get the required indicator? It is clear that the indicator should have been calculated in advance, that is, be in a calculated state constantly, in case of an unexpected visit.

In principle, it is quite simple to fulfill the censorship requirement, you just need to have a calculated total amount together with the balances for each property item. If the censor is satisfied with the total amount, the better, and not be satisfied - let him personally carry out arithmetic verification of the available diptychs. Demand more from the verified, you know, is impossible.

I assume that the Roman, who carried out home accounting, along with the remnants of his property on the current date recorded in the diptych the total amount - the very one in which he swore during the qualification. When changing the property condition, the Roman erased the obsolete record and made a new one, but at the same time, in case of a censor’s visit, he kept a separate diptych with the total amount of his property.

Nothing impossible, right? The censor requires a total amount, and the head of the family politely replies:

"Please, here I have it in the final diptych."

Not understood? Let's do it again.

It was impractical for a Roman who recorded changes in property balances in diptychs to recount the once calculated total, so the Roman could act and probably acted in a different way: he didn’t recount the total result for the indicators recorded on several (tens or hundreds) of diptychs, but made equivalent changes only in changed indicators, including the total result, thereby greatly simplifying arithmetic calculations. Simply put, the Roman performed the accounting entries! So, in my opinion, a double record arose, taking into account, along with real objects (A - assets, and P - liabilities) of the total cost result (K - capital) and the methodological consequences arising from double recording, it is still not quite obvious, but already recognizable.

When the censor entered the Roman house, the owner presented him with documentary evidence of the diptychs stored in the tablinum: first, the one on which the final result was recorded, and, if necessary, a more thorough check, the remaining diptychs, on which the balances appeared for each type of property.

The dialogue between the owner of the family and the censor looked different from the one presented earlier,

"Hello, I am a censor, I need the total value of your property."

"Twenty thousand sisters."

"Submit the result."

“Here you are, my final diptych. See for yourself what is written in it: twenty thousand sisters, a penny in a penny ”.

“The figure makes me doubt. In particular, I doubt that your bull data is true. ”

“Oh great Jupiter, what an undeserved insult! I ask you, dear censor, to go to my family tablinum. Now I will find a diptych in which the bulls are recorded ... here it is, this diptych ... Please see for yourself: I have four bulls. "

“Well, where are they?”

“In the field, dear censor, of course, in the field ... But with the slightest doubt on your part, I can drive them to the stall. It will take a couple of hours, no more. "

"No need, I believe you."

Accounting for equity in ancient Rome did not happen because someone very brainy for no reason came up with a particularly advanced methodology. No - if the dual methodology were invented in other conditions, it would not have the slightest chance of mass distribution! The invention of double-recording occurred because it was convenient for a simple Roman inhabitant to write his own capital as an independent object, along with real property, on a waxed board - for nothing more.

This is the core of my reasoning - the very thing that not one of the historians who adhere to the hypothesis of the origin of double entry in Ancient Rome, or in feudal Italy, or any other hypothesis explains. Well, double-entry was born, and why there? and why she? Yes, because - I reply, - it was precisely in Ancient Rome that the unique political and economic conditions developed: home accounting, balance sheet accounting and the threat of a sudden check of the total property result, which made it methodologically advantageous to register equity as an independent object.

What happened to double recording next?

The Romans began using papyrus and parchment book codes. Later, paper penetrated into Europe - an information medium widely used to this day - which allowed accounting subjects to maintain full income and expense accounting. With income-taking accounting, the need for accounting for capital as an independent object disappeared, so double entry should have lost all relevance for the Romans ... nevertheless, K (capital) continued to be taken into account as an independent object!

Why did it happen? A historical mystery.

The case of maintaining the accounting of equity in terms of income-accounting can only be explained by the established tradition, the habit of completing a business transaction, to edit data in two diptychs, but not in one. If, instead of the departed, another object arrived, the records of these two objects were subject to correction; if the operation was uncompensated, non-reciprocal, the result also had to be corrected - a diptych with capital data. The habit of correcting several objects at once in one operation was so ingrained in the flesh and blood of the Romans that they could not abandon it in the new conditions.

Censuses were canceled, and the Roman registration of household property has sunk into oblivion. However, it was preserved by merchants and money changers (argentarians and trapezites), for whom accounting was an absolutely necessary and natural matter. The emergence of new information media changed accounting technologies, pushed the boundaries, but traders accustomed over several centuries have saved the methodological device that has remained from tabular balance accounting as a harmless and not burdensome (at that time) atavism. Here, at the end of the 15th century, Luca Pacioli came to the forefront of history, guessing to put the methodology of merchant notes in a mathematical treatise, thereby immortalizing his name.

Such a hypothesis about the origin of double-entry bookkeeping is no more fantastic than others, and equally unverifiable.

I do not take all of them — my hypothesis and other hypotheses too seriously — and am generally guided in this matter by the opinion that Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol expressed in Dead Souls:

“First, the scientist ... begins timidly, moderately, begins with the most humble request: is it from there? Isn't this country got the name from that angle? or: does this document belong to another, later time? or: is it not necessary to understand what kind of people are these people? He immediately quotes those and other ancient writers and as soon as he sees some kind of hint, or, just, it seemed to him a hint, he already gets a lynx and invigorates, talks to ancient writers easily, asks them questions and even answers them, completely forgetting about that that began a timid assumption; it already seems to him that he sees this, that this is clear - and the reasoning is concluded with the words: so this is how it was, so what kind of people need to be understood, and so from what point you need to look at the subject! Then publicly from the pulpit, - and the newfound truth went for a walk around the world,

To give the post due intrigue, I’ll inform you that the growth of young and talented ancient Roman IT specialists had a hand in the invention of double-entry bookkeeping. The image of one of them, behind the laptop of the antediluvian model, is attached.

Okay, I joked about the ancient Roman programmer. What is it ancient Roman, when ancient Greek? However, about double-entry bookkeeping - no jokes. So many people cry with burning tears from her that her tongue doesn’t turn around.

For those lucky ones who are far from double-entry bookkeeping, I explain the situation.

The founder of double-entry bookkeeping is considered Luca Pacioli, who published in 1494 the first accounting work entitled “Treatise on Accounts and Records”. The monk-mathematician did not work as an accountant for a day and had a very distant relation to accounting, which is very noticeable from the treatise, which is simply boring to read, how boring it is to read most modern accounting textbooks. This alone indicates that Pacioli was not the author of the methodology, but an elementary compiler (which at that time was not considered shameful).

Most accounting historians are inclined to believe that the real inventor remained unknown: for example, some medieval merchant or the entire merchant family, who for decades or even centuries kept the technology secret from competitors. Or even not a medieval family, but more ancient - the ancient Roman, for example.

I will say right away that I am also inclined to the ancient Roman version. However, one must understand what the main difficulty is. The difficulty is not in obtaining any written evidence of the invention of double-recording - there probably isn’t any such - but in understanding why double-recording was invented.

The purpose of double recording is the most mysterious in the history of its invention!

Double-recording itself is a pretty solid and tightly knocked-down technology. It has a set of well-known advantages and a set of equally well-known disadvantages, but the fact that double recording is a technology cannot be denied.

But - any technology is intended for something, and double-recording is as if it was not intended for anything: the technology itself is like an alien. Imagine a device that has fallen from the sky: some wires, sensors, terminals and connectors, and it’s even more or less clear how it works ... and you’ll tear apart the mission as a whole. So with double recording the same story.

Her device is quite tricky, but if in a nutshell, it looks like this. There are two unequal values: A (asset) and P (passive). If you subtract P from A, you get the difference, it goes without saying. We call the difference K (capital).

We take the formula (the so-called balance equation):

A - P = K

Move P to the right side, we get:

A = K + P

Just look how cool it turned out!

Now, if we begin to register the values of A and P (which is the purpose of accounting), but along with them we also begin to register (not calculate how it begs, namely register!) The difference between them K (capital), then a double record with its debit and credit, and their total posting amount. A debit loan combined in one accounting entry is an addition to equal amounts of equal values, the same with deduction. What happens in this case? The same values will turn out, what else can happen ?!

Such simple arithmetic for the first grade, but why was it - this same accounting balancing - was invented and put into practice, what’s the question?

They explain it in different ways, but each time it is unconvincing: either for checking books, or for calculating capital, or in connection with the appearance of joint-stock companies. The reasons, from my point of view, are all unconvincing. In Russia, they learned about double-entry at the end of the 18th century, another half a century was required for double-entry to be put into practice, but even then the Russians kept their books: regulations were issued, statements were filled out, and property was recounted. Bookkeeping was, but imagine, there was no double entry!

So I put forward my own hypothesis explaining why it was necessary to register K (capital) together with A (assets) and P (liabilities).

According to my version, double recording was invented in Ancient Rome, in connection with the qualifications (here I am not original).

Cens - a census conducted once every 5 years. The qualification itself was as follows. Each legally independent citizen swore an oath about himself: his full name, place of birth, name of his father or (for freed slaves) former owner, age and property subject to tax. On the basis of property owned by the Roman, he was assigned one or another qualification category, and in general - his rights and privileges were determined.

Well, great, but what does double-entry accounting have to do with it? But with it.

In the directories it is written that the censors, who were elected from among the consuls (former consuls), were responsible for conducting qualifications in ancient Rome. The censors had the right to reduce the number of civil rights that the Roman enjoyed according to the results of the qualification, and even had the right to remove the senator from the Senate. At the same time, according to the directories, not only purely political and administrative considerations were taken into account, but also the personal life of each citizen, that is, the censors took on the role of guardians of morality.

Well, how did you get an official with such broad powers? I could not establish whether the censors had the right to belittle the Romans in civil rights only during or between the qualifications, that is, on an ongoing basis, but strongly suspect that they had. Otherwise, how could statesmen observe the morality of fellow citizens if qualifications were passed once every five years? The status of an official with such meaningful functions as the censor should have been constantly maintained, therefore, the authority of the censor was required to include an ongoing audit of the censorship lists.

Justified Assumption? It seems reasonable to me.

Then figure out how the censors could revise the lists of Roman citizens in between censuses. The essence of the audit, for any of its national features and legal formalities, could be reduced to one thing: a censor was declared to a Roman citizen in order to check his property status - we will not forget that an audit of the censorship lists of Roman citizens involved first of all a check of property status, and then the rest . Based on the results of the property check and the observations accompanying it, the censor determined: is the behavior of this Roman citizen moral? should not this belittle the rights of a Roman? Is he worthy of belonging to a well-known social stratum?

If I'm right, it becomes clear that whip, which the ancient Romans were forced to keep a home written record: censors.

We conclude that each law-abiding Roman, for fear of visiting the censor, kept a record of household property. This does not explain the invention of double-entry, but brings it closer, especially if you find out what kind of written records the ancient Romans could keep at the time of the qualification.

The main thing is not even what, the main thing is on which medium.

In ancient Rome, according to modern reference books, the following information carriers were used: papyrus, wooden planks, parchment, tree bark, clay shards, plaster. On which of the information media did the venerable fathers of the Roman families keep home records, and in what incomprehensible way did the media use associated with the invention of double-entry?

What medium did the ancient Romans use for writing records of household property?

We bark the tree bark, clay shards and plaster immediately: it is simply difficult to imagine.

I suppose that the papyrus was not used by the Romans to run accounts for the reason that it was a little expensive after all. Throughout the ancient period, papyrus was the main writing material for the Mediterranean countries, but only when performing certain types of writing: for example, literary texts on papyrus scrolls were written and legal contracts were drawn up, but daily business records were not, for reasons of economy. Otherwise, household papyri would be preserved in mass quantities, but they did not survive: it means that it simply did not exist.

Then parchment codes, which, as an information medium, are much more durable and attractive than papyrus scrolls? It is also unlikely. Parchment was more expensive than papyrus - cattle skin after all! - Therefore, its use in home accounting looks even less likely. Secondly, the use of parchment does not go according to chronology.

To understand the sequence of events, I compiled the following chronology. Estimate yourself what and when, according to official reference data, what happened.

3 thousand BC - the first surviving papyrus;

578-534 years. BC. - the establishment of qualifications, initially property;

mid 5th century BC. - the value of qualifications has increased significantly;

443 BC - introduced the position of censor;

312 BC - conducting the first cash qualification;

OK. 180 BC - start of parchment production;

mid 1 century BC. - the censor position is liquidated;

74 A.D. - cancellation of qualifications;

1 century AD - the existence of codes has been reliably attested;

2 c. AD - the invention of paper;

4-5 centuries AD - the scroll began to be supplanted by the code;

8 c. AD - paper penetration in Europe.

11 century AD - cessation of the use of papyrus as writing material.

Parchment began to be produced a hundred-odd years after the first cash qualification and two and a half centuries before their cancellation. While parchment production was established, which was unlikely to happen quickly, censorship began to decline ... and taking into account the high cost of parchment ... and the fact that parchment codes appeared during the abolition of censorship ... It is very doubtful that the ancient Romans who lived in the age of censorship used to conduct home accounting parchment.

If historians do not lie, and home accounting in ancient Rome, carried out during the time of qualifications, was nevertheless written, it remains to be assumed that it was carried out on diptychs — two-part writing boards covered with a layer of wax: the letter on them could be scratched with a stylus and then erased. (The drawing on the ancient Greek vase does not depict a laptop, but a diptych writing instrument ... you guessed it, of course).

How many diptychs were required to record the property of one family? Let's figure it out. If we assume that no more than forty lines could be written on one diptych (twenty on one board and twenty on another - what do you think fit better? Is it a sharp stick on the waxed surface?), And the total number of records was, let’s put , a thousand (household utensils, pets, slaves, etc.), it turns out twenty-five diptychs ... the size of a laptop. How do you like compact home accounting, not the largest family, on twenty-five laptops?

In favor of the assumption that home accounting was conducted in diptychs, historians friendly mention of a special counting room ( tablinum ) for storing home accounting documents. Term tablinum- “archive” is an etymologically related tabula - “board, plate, table”, and tabella - “board, plank”. So what information media were kept by the ancient Romans in tablinum ? Is it papyrus or parchment?

And the most important.

During the qualification, the Roman swore oath of magnitude (total value balance), but not of property turnover. It does not follow from the definition of qualifications in handbooks that ancient Roman law obliged citizens to keep receipts and expenditures ... and where is the evidence that the ancient Romans really kept it, as most historians unreasonably assume?

The difference between profit and loss accounting and accounting for balances (balances), I hope, is clear: in the first case, it records how much property has left the farm and how much has arrived (income / loss), and in the second case, only cash property balances as of the current date are recorded. For balance accounting, the ability to add new ones over old records was very useful and desirable. For daily rough accounting, something inexpensive and non-expendable was needed, and a simple waxed board was, without a doubt, accessible and common material, and it did not need to be thrown away when updating the record.

This is where everything converges into one dense logical point: the fact of conducting home accounting is rather unusual for today; balance accounting, which the Romans were able to carry out on the media available to them; the multiplicity of information carriers required for accounting; censors who had the right, on the pretext of a censorship check, to invade Roman dwelling; and the subject of our consideration is a double entry.

What do you think, would a high official, who has applied to a Roman house to revise his property status, recount the accounting records captured in dozens, and possibly hundreds of diptychs? No normal official, including the ancient Roman, would not agree to such a mockery from his point of view. How do you imagine the dialogue between the censor and the censored Roman?

"Hello, I am a censor, I need the total value of your property."

"Twenty minutes."

“How can you confirm it?”

“And there’s ninety diptychs in my tablinum. If you want, recount. ”

No, the censor would require first to familiarize himself with the general figure of the current property status, then, in case of doubt about the authenticity of the credentials, proceed to a detailed check. To wait until the revised owner of the family summarizes a thousand or more digits, the censor would also not agree, wishing that the final figure be presented to him immediately.

From where did the Roman subject to censorship, at the first request of the censor, get the required indicator? It is clear that the indicator should have been calculated in advance, that is, be in a calculated state constantly, in case of an unexpected visit.

In principle, it is quite simple to fulfill the censorship requirement, you just need to have a calculated total amount together with the balances for each property item. If the censor is satisfied with the total amount, the better, and not be satisfied - let him personally carry out arithmetic verification of the available diptychs. Demand more from the verified, you know, is impossible.

I assume that the Roman, who carried out home accounting, along with the remnants of his property on the current date recorded in the diptych the total amount - the very one in which he swore during the qualification. When changing the property condition, the Roman erased the obsolete record and made a new one, but at the same time, in case of a censor’s visit, he kept a separate diptych with the total amount of his property.

Nothing impossible, right? The censor requires a total amount, and the head of the family politely replies:

"Please, here I have it in the final diptych."

Not understood? Let's do it again.

It was impractical for a Roman who recorded changes in property balances in diptychs to recount the once calculated total, so the Roman could act and probably acted in a different way: he didn’t recount the total result for the indicators recorded on several (tens or hundreds) of diptychs, but made equivalent changes only in changed indicators, including the total result, thereby greatly simplifying arithmetic calculations. Simply put, the Roman performed the accounting entries! So, in my opinion, a double record arose, taking into account, along with real objects (A - assets, and P - liabilities) of the total cost result (K - capital) and the methodological consequences arising from double recording, it is still not quite obvious, but already recognizable.

When the censor entered the Roman house, the owner presented him with documentary evidence of the diptychs stored in the tablinum: first, the one on which the final result was recorded, and, if necessary, a more thorough check, the remaining diptychs, on which the balances appeared for each type of property.

The dialogue between the owner of the family and the censor looked different from the one presented earlier,

"Hello, I am a censor, I need the total value of your property."

"Twenty thousand sisters."

"Submit the result."

“Here you are, my final diptych. See for yourself what is written in it: twenty thousand sisters, a penny in a penny ”.

“The figure makes me doubt. In particular, I doubt that your bull data is true. ”

“Oh great Jupiter, what an undeserved insult! I ask you, dear censor, to go to my family tablinum. Now I will find a diptych in which the bulls are recorded ... here it is, this diptych ... Please see for yourself: I have four bulls. "

“Well, where are they?”

“In the field, dear censor, of course, in the field ... But with the slightest doubt on your part, I can drive them to the stall. It will take a couple of hours, no more. "

"No need, I believe you."

Accounting for equity in ancient Rome did not happen because someone very brainy for no reason came up with a particularly advanced methodology. No - if the dual methodology were invented in other conditions, it would not have the slightest chance of mass distribution! The invention of double-recording occurred because it was convenient for a simple Roman inhabitant to write his own capital as an independent object, along with real property, on a waxed board - for nothing more.

This is the core of my reasoning - the very thing that not one of the historians who adhere to the hypothesis of the origin of double entry in Ancient Rome, or in feudal Italy, or any other hypothesis explains. Well, double-entry was born, and why there? and why she? Yes, because - I reply, - it was precisely in Ancient Rome that the unique political and economic conditions developed: home accounting, balance sheet accounting and the threat of a sudden check of the total property result, which made it methodologically advantageous to register equity as an independent object.

What happened to double recording next?

The Romans began using papyrus and parchment book codes. Later, paper penetrated into Europe - an information medium widely used to this day - which allowed accounting subjects to maintain full income and expense accounting. With income-taking accounting, the need for accounting for capital as an independent object disappeared, so double entry should have lost all relevance for the Romans ... nevertheless, K (capital) continued to be taken into account as an independent object!

Why did it happen? A historical mystery.

The case of maintaining the accounting of equity in terms of income-accounting can only be explained by the established tradition, the habit of completing a business transaction, to edit data in two diptychs, but not in one. If, instead of the departed, another object arrived, the records of these two objects were subject to correction; if the operation was uncompensated, non-reciprocal, the result also had to be corrected - a diptych with capital data. The habit of correcting several objects at once in one operation was so ingrained in the flesh and blood of the Romans that they could not abandon it in the new conditions.

Censuses were canceled, and the Roman registration of household property has sunk into oblivion. However, it was preserved by merchants and money changers (argentarians and trapezites), for whom accounting was an absolutely necessary and natural matter. The emergence of new information media changed accounting technologies, pushed the boundaries, but traders accustomed over several centuries have saved the methodological device that has remained from tabular balance accounting as a harmless and not burdensome (at that time) atavism. Here, at the end of the 15th century, Luca Pacioli came to the forefront of history, guessing to put the methodology of merchant notes in a mathematical treatise, thereby immortalizing his name.

Such a hypothesis about the origin of double-entry bookkeeping is no more fantastic than others, and equally unverifiable.

I do not take all of them — my hypothesis and other hypotheses too seriously — and am generally guided in this matter by the opinion that Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol expressed in Dead Souls:

“First, the scientist ... begins timidly, moderately, begins with the most humble request: is it from there? Isn't this country got the name from that angle? or: does this document belong to another, later time? or: is it not necessary to understand what kind of people are these people? He immediately quotes those and other ancient writers and as soon as he sees some kind of hint, or, just, it seemed to him a hint, he already gets a lynx and invigorates, talks to ancient writers easily, asks them questions and even answers them, completely forgetting about that that began a timid assumption; it already seems to him that he sees this, that this is clear - and the reasoning is concluded with the words: so this is how it was, so what kind of people need to be understood, and so from what point you need to look at the subject! Then publicly from the pulpit, - and the newfound truth went for a walk around the world,

Only registered users can participate in the survey. Please come in.

How do you feel about double recording?

- 59.6% No way, thank God! 306

- 11.8% The ingenious invention of mankind. 61

- 16.1% Double recording has its pros and cons. The minuses must be abandoned, the advantages developed. 83

- 12.2% Hopelessly outdated! Atu, overboard her story! 63

Who do you think invented double-entry?

- 5.3% Luca Pacioli. 26

- 8.6% Remained anonymous genius. 42

- 7.2% Medieval merchants. Double entry is a collective invention. 35

- 1.6% Ancient Roman state. 8

- 21.4% I believe the author of the post. 104

- 55.6% I have no idea. 270

How many double entries exist?

- 13.9% Not For Long. 53

- 27.5% For a long time. 105

- 36.7% Double recording will not die, it will be modernized into something more perfect. 140

- 21.7% Double-entry - forever, as it expresses the law of nature. 83