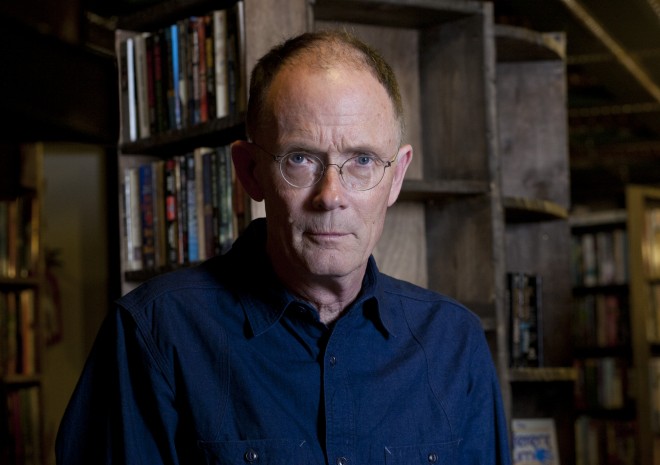

Interview with William Gibson to Wired Magazine. Part 2

- Transfer

The first part is about why science fiction writers almost always incorrectly predict the future.

Once, William Gibson spent almost five years of his life studying the history of mechanical watches, without any practical purpose, chasing knowledge for the sake of knowledge. “I wanted to try to become a real otaku in this matter,” he explains.

Today, the author, in whose books, starting with the classic "Neuromancer" of 1984, an imaginary world has grown, surprisingly echoing modernity, says that he does not have a serious, passionate hobby. And now he spends his free time, which used to go on an old watch, on Twitter.

In the second part of the interview, one of the most extraordinary science fiction writers and prominent thinkers talks about the Internet and social media, about his passion for hours and punk rock and why he is afraid of nostalgia.

Wired: You have some interesting thoughts on social media. You once said: “I was never interested in Facebook and Myspace, because they are too hierarchical. They look like huge supermarkets. But Twitter - it is like an ordinary busy street. You can easily stumble on anyone there. ” Could you tell us more about this?

Gibson: My friend Doug Copelandrecently tweeted something like that. It was about the fact that he was once again trying to figure out Facebook. He said: “It's like Twitter, only with mandatory homework.” Very suitable description. Twitter is easier - you just go there and that’s it. And people around - they just are. There is no structure and hierarchy - I like it, it is very democratic, and this is not enough in other, more structured social networks. However, in fact, this is all at the level of sensations, I am now too much hit on abstraction and theory.

Wired: At one time you were addicted to buying old mechanical watches on eBay and described this addiction in the article " My Obsession ", which was included in the collection "Distrust That Particular Flavor". What are you obsessed with now? Could be Twitter?

Gibson:The whole story with the watch was just an experiment on itself. When I started, I thought that I could never have a real, adult hobby that was completely unrelated to anything that I usually do in life. A hobby that would require an impossibly steep and difficult learning curve. But I did it.

I studied everything related to watches for four or five years ... I reached such a level that I could already pass for an intelligent and advanced amateur in the company of world-class experts. But by then I realized that I was not at all interested in collecting any one narrow category of things. This feature of collecting has always been disgusting to me.

I did not want to collect anything. I just wanted, for no practical reason, to know a lot about one thing. I achieved the goal and almost reached the end of the curve. I felt the pure causeless pleasure of being versed in a vast and completely useless area. And that was the end of it for me [laughs]. I didn’t have to do this forever. And I never did anything like that again. It was a one-of-a-kind experiment. But it was very cool - then I met many surprisingly unusual people.

All this would have been impracticable, if not for the Internet. Previously, if you wanted to study something like this in detail, you had to be a complete loon - and travel the whole world in search of the same loonies who had already studied this subject before you in order to adopt their knowledge. It was so difficult and so dependent on the will of chance that there were only a few such people.

And now you can live in a remote village in the jungle of Brazil, and decide one morning: “I want to know absolutely everything about stainless steel sports watches made in the 1950s,” and if you can use the Internet, you will be able to master thesis in a year protect on this topic. Yes, I knew a lot of people who could.

Perhaps now Twitter in a sense has occupied this niche of my time. Wired:

How are the plans for the adaptation of Neuromancer moving? Talk about her has been going on for several years.

How are the plans for the adaptation of Neuromancer moving? Talk about her has been going on for several years. Gibson: I would only talk about this if the idea was finally bent, but since it is not, I do not want to say anything. I do not like to discuss someone else's unfinished work. She's advancing, that's all. If something out of the ordinary happens, I will write about it on Twitter. Hear something from other sources - immediately check if I have tweeted about it. If so, it means the truth.

Wired: In the 2000 documentary No Maps for These Territories“you made a lot of bold predictions about the technologies of the future, and many of them have stood the test of time. You say you don’t believe in the predictive power of science fiction, but it seems that you are good in the future.

Gibson: Maybe ... I don’t know for sure - I I watched the film only once when it was released to make sure that I didn’t say nonsense and that my words weren’t misinterpreted.I suspect that if you saw all the material that was not included in the final version, you would understand that in fact, since the work on the film was going on For only years, they had the opportunity to select only those pieces that found confirmation.

This is a common technique for playing futurology. Everyone who, in one form or another, trades in the prediction of the future, whether it's science fiction or analysts and advisers, is very interested in making their predictions look accurate. If I were absolutely cynical yap, I would also try to convince everyone that I see the future. But in fact, I never wondered whether my predictions would come true or not.

Unfortunately, the predictive power of science fiction has traditionally occupied an important place in marketing. “Listen to her, she knows the future!” - the old song of the booth barker, like the world. This is not the essence of science fiction. Fiction provides an excellent set of tools, using which you can parse and explore the incomprehensible and ever-changing present in which we live, and which can be quite uncomfortable. This is how I see my work. But an enterprising publisher can see it in a completely different way.

Wired: In your opinion, the popularity of TED and other similar conferences, pierced by a dramatic visionary spirit, has similar roots?

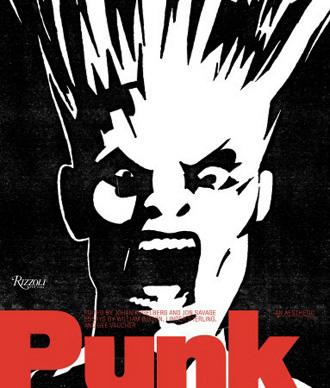

Gibson:Yes, I think that the TED phenomenon is based on the same cultural impulses that we just talked about. "Wow! Now they will tell us how everything will be ”... Usually I’m not very interested in such things. And they do not often invite me to such events. This is probably for the best. Wired: The other day, Punk: an aesthetic is published , which also contains your essay on punk culture from the 1970s. I would like to hear your thoughts about music in general and punk rock in particular. Gibson: I'm an old-fashioned punk, really an old-fashioned punk [laughs]. I still have a box in the basement with a bunch of old records. There are quite valuable specimens that I managed to get with great difficulty. There was a thrill in this - that it was hard to get them. Wired:

Now listening to music is not so interesting, because you can easily find anything you want?

Gibson:Well, nostalgia is such an alarming bell for every person. Whenever I catch myself thinking about what the “X” used to be, that it was better than now, or that the “Y” is not like that in my youth, I feel my pulse, checking to see if it’s sick am i conservatism? [laughs] No, however, throughout the history of mankind, suffering voices have been heard: “Well, what kind of youth have you gone? ... Here we are in their years!” I hear this constantly since I became old enough to pay attention to this, and I am desperately trying to hold back so as not to start grumbling myself. Because if I cannot resist, then, in a sense, I will be done away with. At least with my ability to predict the future. I hate things that I loved go back in time. But if it makes me resist change, that means I have a problem. Here is what I think of it.

What is now is somewhat different from what it was before. But in some ways it remains the same. We just look at it from different angles. I think that over the past 30 or 40 years there have been fundamental changes that we still have not really figured out. Because these changes are happening to us, here and now. We are within them; we are unable to embrace them whole. Time will put everything in its place.

I like to compare - to find a foothold in this cycle - what the British Victorians thought of themselves, and what we think of them now. Because there is nothing in common between these two ideas. They would probably die on the spot if they knew our opinion. They considered themselves the crown of creation. We firmly believe that this is not so. From our point of view, they were inferior, flawed and terribly narcissistic. I think that the same way from the future will look at us. But we are no more able to look at ourselves from the side than the Victorians were capable of.

This is normal, I just think that you should not forget about it. And this applies to me too. I am not saying that I am special, that I am above the crowd.

Wired:Are you listening to something from modern music? Do you continue to listen to something from the time of your youth - if not with nostalgia, then with tenderness?

Gibson: One of the consequences of the digital era for me personally is that music has become completely timeless. I don’t have a clue and don’t want to have a clue about what’s happening in music right now, because now it’s not important. Now, last week, 30 years ago? What's the difference? Everything is on Youtube. So I can discover something ten years late, or I can be one of the first. It is timeless. It’s like a long, long calendar for many years at once. And it started a long time ago.

Since the Beatles appeared, not just as a group, but as a cultural phenomenon, like Beatlemania, parents around the world have been able to watch their children discover the Beatles. This is still happening. It usually takes two weeks for children to swallow them whole. Sometimes longer. And that’s it - the Beatles entered them.

In some incomprehensible way, the Beatles live out of time - their image and their recordings live. This is not 60s music. This is something ... eternal. An amazing thing. Whenever I’m driving in a car and the radio is tuned to some classic rock station, a fantastic question comes to my mind: “Could I hear the exact same playlist of the year 2046? Will anyone even listen to this in 2046? ”Maybe. Will this music ever disappear? In this sense, we are discovering new territories. Maybe…

Wired: Someone once told me that Led Zeppelin is like sound wallpaper - part of the environment, something inevitable and ubiquitous, almost like furniture.

Gibson: I know this feeling, that's for sure. Take for example "Stairway to Heawen." How long has each of us heard this song in our lives? Many hours! You could well spend 30 or 40 hours of your life with this music. I hope that at this time you were busy with something pleasant, because this watch can no longer be returned. This is a very strange thing that has become familiar to us, but completely amazing for our very recent ancestors.

Wired:What you said about timeless music reminded me of your words about cities. You once said: “In cities, the past, present and future can exist side by side. This is a common thing in Europe - not fantasy, not fiction. And in American fiction, the cities of the future are always new with the needle - to the last inch. "

Gibson:I think that my attitude to big cities was formed due to the fact that I grew up beyond their borders. My childhood was spent in a tiny town away from megacities. Those few really big cities that I visited as a child were completely different. And they really interested me. It seemed to me that cities emit the rays of television and the media. And I spent more time in these beams than in the real environment, and therefore was happy when I finally managed to leave my small town in a megalopolis. I live better and happier in big cities. I'm at ease.

I felt like a black sheep from the fact that I liked the big cities, but it seems that most of humanity is moving in the same direction. Every year, more and more people move into giant human anthills. The strength that draws us into cities is largely that the chances of getting luck are much higher in a big city. Unless, of course, you want to be a farmer or something like that.

The next part is about punk rock, internet memes and “Gangnam Style”.