Hg Init: Part 2: The Basics of Mercurial

- Transfer

This is part two of a series of Hg Init: Tutorial Mercurial by Joel Spolsky ( by Joel Spolsky ). You might also want to read the first part of Retraining for Subversion Users .

This is part two of a series of Hg Init: Tutorial Mercurial by Joel Spolsky ( by Joel Spolsky ). You might also want to read the first part of Retraining for Subversion Users . Even if you work alone, then you should use Mercurial. So you can get all the charms of version control. This part will show how easy it is to add a directory to Mercurial to easily track previous versions.

Part 2. Mercurial Basics

Mercurial is a version control system . Developers use it to administer source code. She has two main purposes:

Mercurial is a version control system . Developers use it to administer source code. She has two main purposes:- It stores all previous versions of each file.

- It can combine different versions of your code, that is, employees can independently work on the code and then merge their changes

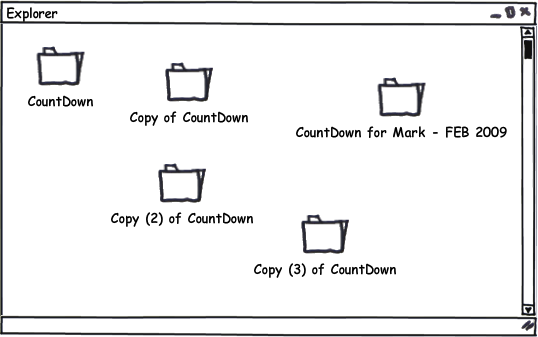

Without Mercurial, you could try to preserve previous versions by simply creating many copies of the directory with the code:

It is dreary, requires a lot of disk space and creates confusion. Better to use a version control system.

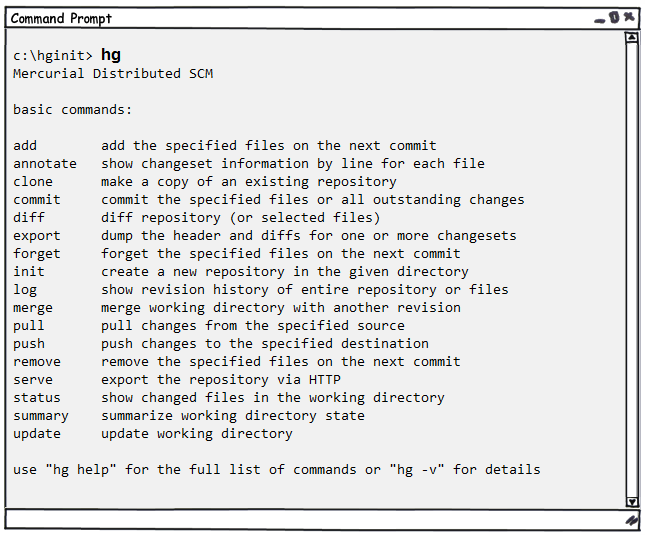

Most people work with Mercurial through the command line interface. This can be done on Windows, Unix, and Mac. The command for Mercurial is

hg:

If executed

hgwithout parameters, you will get a list of the most frequently used commands. You can also try running hg helpto get a complete list of commands. In order to take advantage of version control, you need a repository. The repository stores all previous versions of all your files. In fact, to save disk space, all previous versions will not be stored - only a compact list of changes will be stored.

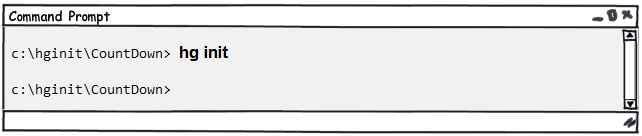

In the old days, having a repository was a big deal. You needed to have a central server and you had to install software on it. Mercurial is a distributed system, so you can use it without a fancy central server. You can use Mercurial using your computer alone. And getting the repository is super easy: you just go to the directory with your code ...

... and run the command

hg init:

hg init

creates a repository.

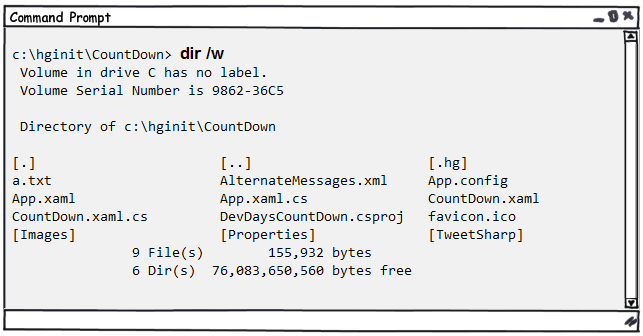

Wait a minute, did something happen? It looks like nothing has changed. No, if you look better, you will see that a new directory has appeared

.hg:

This is the repository! This is a directory with everything Mercurial needs to work. Settings, previous versions of files, tags, an extra pair of socks in case of rain, and more. Do not climb there. You almost always should not bother with this directory yourself.

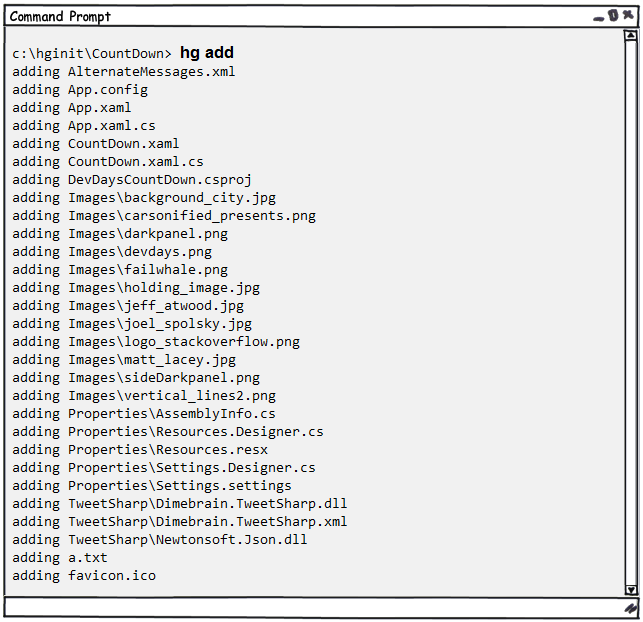

Well, since we now have a freshly baked repository, we will want to add all the source files to it. It is also simple: you just need to perform

hg add.

hg add

Marks files as scheduled to be added to the repository. Files will not actually be added until you commit the changes.

There is one more step ... you need to commit your changes . Which changes? The fact of adding all these files.

Why are you forced to commit changes? When working with Mercurial, committing changes means: "Hey, this is how the files now look, so remember them, please." It’s like making a copy of the entire catalog ... every time you have something changed, and you like it like, then you commit the changes.

hg commit

saves the current state of all files to the repository.

Mercurial will launch the editor so that you can print a comment on the changes. You just need to write something to remind you of the changes made.

After saving and exiting the editor, your changes will be committed.

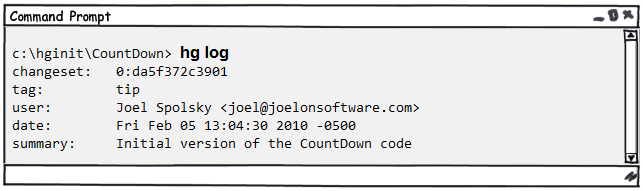

You can follow

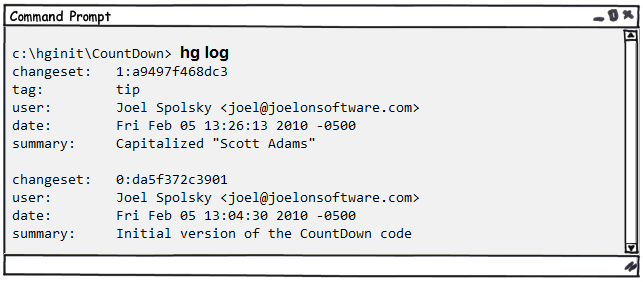

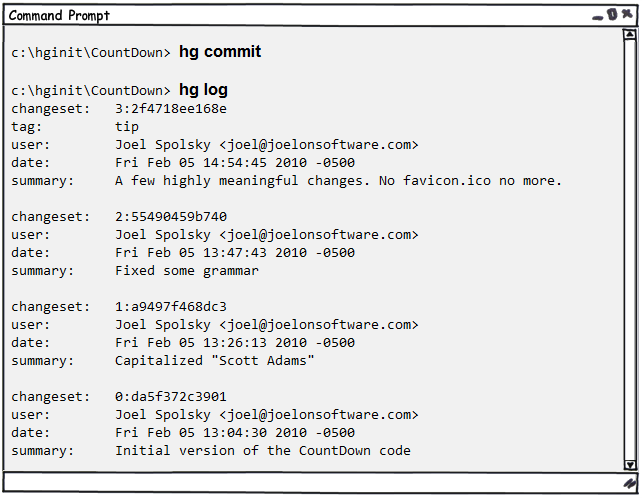

hg logto view the change history. This is like a blog for your repository:

hg log

Displays the history of changes committed to the repository.

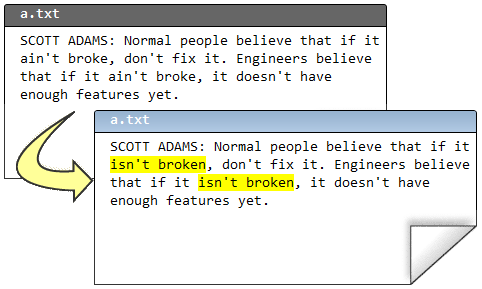

Let's change the file and see what happens.

Since we made the change, we can commit it using

hg commit:

Note that Mercurial guessed that only one file, a.txt, was changed:

And now, after I committed (committed the changes), let's look at the history:

How any current blogger, Mercurial puts the newest at the beginning.

I'm going to make another change, just to amuse myself.

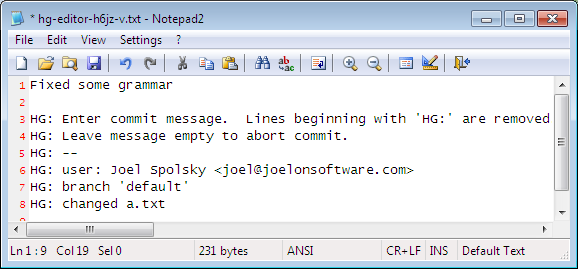

I commit (commit changes):

My message to the commit:

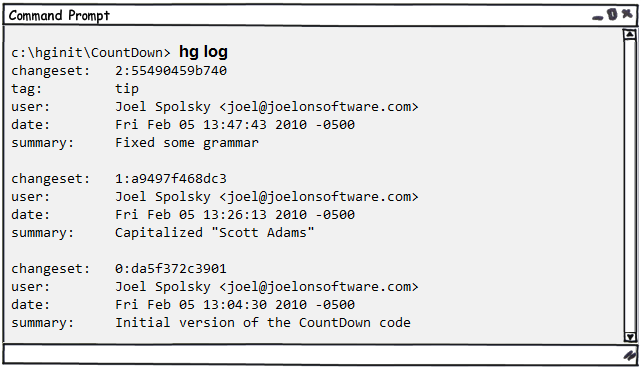

And what do we have in history now?

Well, that was fun. I made several changes and every time I made a significant change, I committed it to the repository.

I know, you are now thinking: "JOEL, ALL THIS LOOKS WASTE WASTE TIME." Why all this katavasiya with commits?

Patience, my young friend. You are about to learn how to capitalize on all of this.

To start: let's say you made a big mistake in the editing process.

And then, my goodness, in addition to everything, you deleted a couple of very important files.

In times when there was no Mercurial, all this could become a good reason for going to the system administrator. There, with tears in your eyes, you would ask him a piercingly sad question: "Why does the backup system“ temporarily "not work for the past eight months."

System administrator everyone's name is taco, too modest and does not have lunch with the rest of the team. In those rare cases when he is not sitting in his wheelchair, you can see a triangular salsa- colored spot where drops falling from his legs, drops from his Mexican snacks. These drops guarantee that no one will take his chair, although this is one of the excellent chairs from Herman Miller , bought by the founders of the company for their loved ones, and not the usual budget office something, because of which everyone has sore backs.

In any case, there is no backup, yeah.

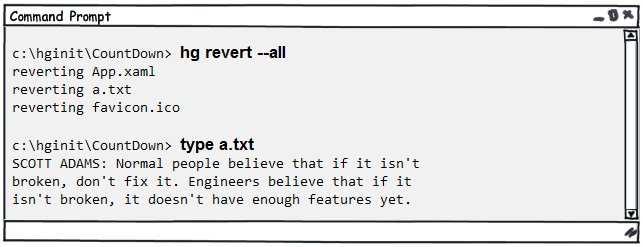

Thanks to Mercurial, if you don’t like what you did, you can execute a convenient command

hg revertthat immediately returns your directory to the form it was in at the time of the last commit.

hg revert

returns the changed files to the view fixed in the repository.

I used the argument

--allbecause I wanted to return all the files to their previous state. Thus, when you work on source code using Mercurial, you:

- Make changes

- Evaluate if they fit

- If suitable, then do

commit - If not suitable, then do

revert - Goto 1

(I know. I use the command line on Windows, and even the GOTO operator - I am the worst programmer of all who have ever lived.)

Over time, you may forget what you stopped at and what you changed since the last commit. Mercurial keeps track of all this for you. All you need to do is execute

hg statusand Mercurial will give you a list of modified files.hg status

displays a list of modified files.

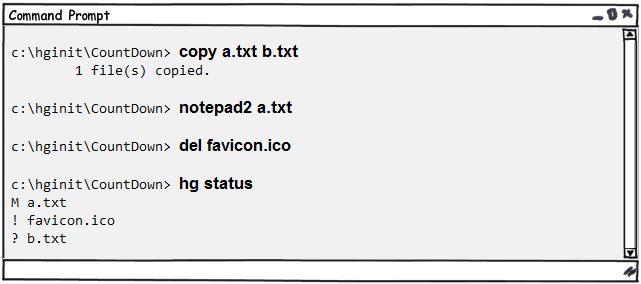

Suppose I created one file, edited another, and deleted the third.

hg statusdisplays a list of modified files by adding an icon at the beginning of each line. This icon indicates what happened. “M” means “Modified” - the file has been modified. "!" means no - the file should be here, but somewhere gone. "?" means that the state is undefined - Mercurial knows nothing about this file. Doesn't know yet. Let's deal with the changes one by one. Here's what has changed in the a.txt file ? You can forget that you have changed. Hell, I barely remember what I usually eat for breakfast. And it is especially worrying that these are always CHEERIOS crispy rings . In any case, a.txt is changed. What has changed?

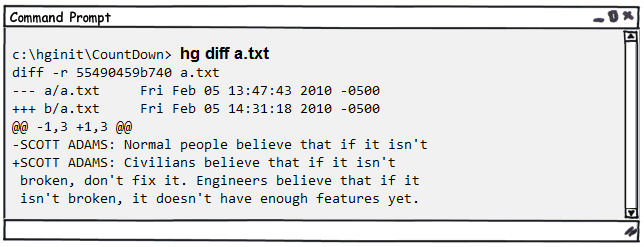

And there is a command for this:

hg diff will tell you exactly what happened to the file from the last commit.hg diff

shows what has changed in the file.

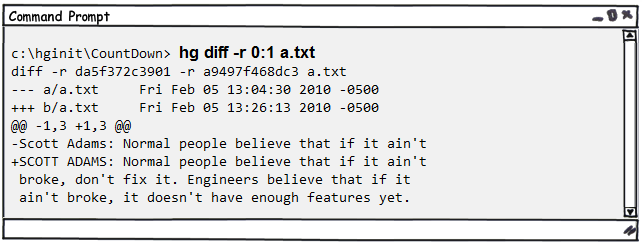

The format of the result is a little incomprehensible, but the most important is that you can see the lines starting with a minus (this is what was deleted) and the lines starting with a plus (this is what is added). So you can see that “Normal people” has been replaced by “Civilians”.

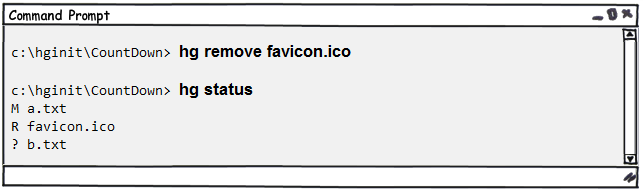

Now about that missing favicon.ico file . As already mentioned, if you really did not plan to delete it, then you can execute the command

hg revertto restore it. But suppose you really wanted to delete it. Each time you delete (or add) a file, you must report this Mercurial event.hg remove

Marks files as scheduled for removal from the repository. Files on the disk will not be deleted until you commit the changes.

“R” means “Removed,” that is, is marked for removal. During the next commit, Mercurial will delete this file. ( The history for this file will be saved in the repository, so of course we can always get it back.) And finally, you need to add this new b.txt file :

“A” means “Added”, that is, is marked for addition. Noticed that I spill over to write

hg statusevery time? For Mercurial, a minimal set of letters that uniquely identifies a command is sufficient, and stonly one command begins. Having sorted out the questions and exclamation points, I can continue and make changes:

What else is worth paying attention to in the output

hg log: line changesetdisplays the number of each commit. In fact, there are even two numbers: a short convenient one like “0” for the first revision and a long incomprehensible hexadecimal, which you can ignore for now. Remember that Mercurial stores enough information in the repository to recreate any version of any file.

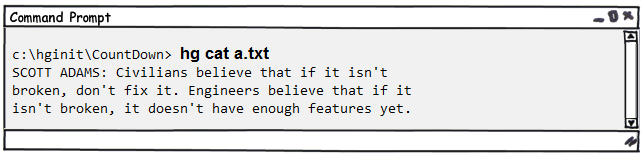

First of all, with a simple command

hg catyou can display the contents of any version of any file to the console. For example, here's how to see what is now in the a.txt file:

hg cat

displays the contents of any file for any revision.

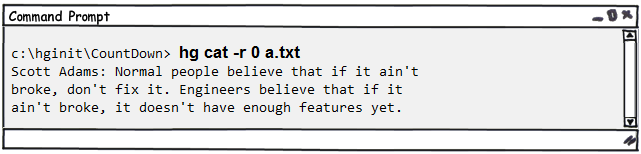

In order to see how the file looked before, I can simply specify the desired number of changeset (changeset from the log) using the argument

-r(“revision”, that is, revision):

If the file has complex contents or a large length, but it has changed only a little, then I can use the command

hg diffwith an argument rto output the difference between the two revisions. For example, here's how to see the difference between revisions 0 and 1:

And finally, - I hope that you have not fallen from fatigue yet - before finishing this part, I want to show you one more small trick : with the help of the command

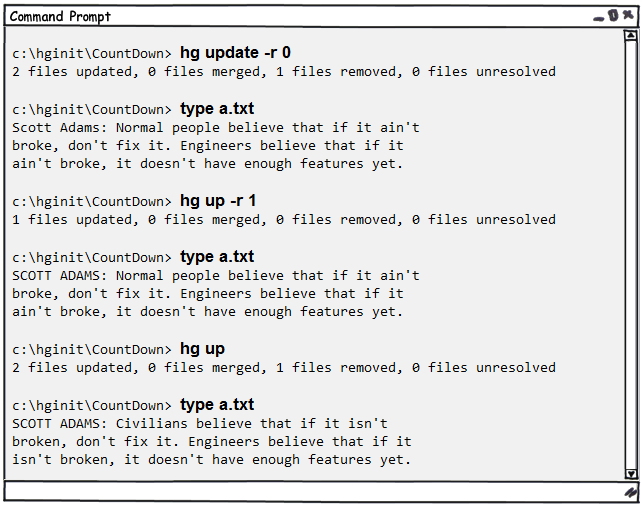

hg updateyou can move forward and back to the time of creation of any revision. Well essentiallyyou won’t be able to move into the future, although that would be super cool, yes. You, with only four revisions, could perform hg update -r 103994and get a really cool version of your source code. With gravitsapoy and other futuristic things. But of course this is not possible. What is actually possible is to return to any revision. Watch your hands:

hg update

brings the working directory to a state, like a given revision.

In fact, for moving back and forth between revisions, it

hg updatemakes memorized changes to the files. If the file was added or deleted, this command adds or removes it to disk. Execution hg updatewithout additional parameters brings the working directory to the state as in the most recent revision.check yourself

Fine! This part is finished. Here is all that you should be able to do at the moment:

- Create repository

- Add or remove files from the repository

- After making changes, review what has been done and then

- ... commit changes if you like them

- ... or roll back changes if you don't like

- View previous versions of files or bring the working directory to a state like that of some revision.

Continued here:

Hg Init: Part 3. We get used to working in a team