The lack of copyright contributed to the technological revolution in Germany in the 19th century

In the 19th century, the German state experienced strong industrial growth, which was accompanied by a multiple increase in scientific publications and the total number of books published in the country. The unexpected love of the Germans for books made the literary critic Wolfgang Menzel in 1836 call Germany "a nation of poets and thinkers."

For example, in 1843, German publishers published about 14,000 new books, most of which were scientific publications. If we take into account the number of population, then this is the same as it is published today, in the 21st century. For comparison, about 1,000 new works were published in the British Empire that year.

What is the reason for such a rapid economic and scientific development? Economic historian Eckhard Höffner believesthat the whole point is the lack of copyright.

Great Britain adopted copyright in 1710, and the largest German state, Prussia, only in 1837. At that time, Germany was divided into many lands and many years passed until the new concept became widespread.

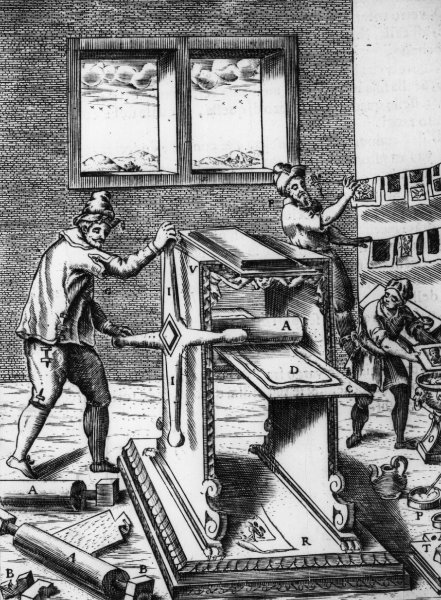

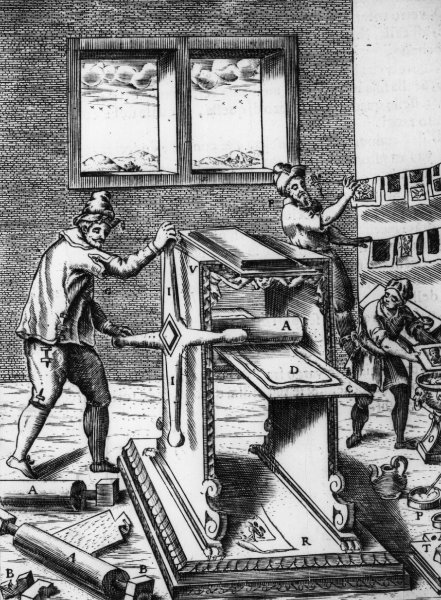

Printing press in the 17th century. At that time there was no strict copyright even in England, and printers could plagiarize and print any kind of literature in any quantity. They also made large print runs of cheap publications for the mass market ..

Hoffner's economic work is the world's first serious scientific study on how copyright affects a country's development over a long time period. It is based on a direct comparison of two neighboring countries, and the conclusions reached have already caused an unhealthy liveliness in the academic environment. Until now, it was believed that copyright guarantees the prosperity of the book market. Like, authors get motivation to write only if they are fully confident in protecting their rights. History shows that this is not entirely true.

English publishers have tried to maximize the benefits of obtaining the right to an exclusive publication. They published a circulation of no more than 750 copies and sold it at maximum prices, the cost of the book often exceeded the weekly salary of an educated worker. Publishers made very good money on such a scheme. It is known that so far the first edition of the book in the premium version brings the lion's share of revenue to the publisher, while the next circulation in the paperback is sold at the cost of it. London publishers were limited to the first edition. Book buyers were wealthy aristocrats, wealthy and noble, and books were equated with elements of luxury. In a few libraries, the most valuable volumes were bolted to shelves in chains to protect against thieves.

In those same years, publishers and plagiarists operated in Germany who could cheaply reprint any book without fear of punishment. Book publishers made not only expensive publications for a wealthy public, but also cheap paperback books for the mass buyer. As a result, a book market has developed that is completely unlike the British. Bestsellers and scientific papers came out in Germany in huge print runs at extremely low prices, so that even in the farthest corners of the country, the poorest people could get a hold of books and make up a small library of pirated publications.

The presence of a huge readership encouraged scientists to publish the results of their work. According to Hoffner, an entirely new form of disseminating knowledge was born instead of the previously existing system of education at school or university or the transfer of knowledge from teacher to student.

Students throughout Germany received a host of the latest scientific treatises on chemistry, mechanics, engineering, optics and steel production. In England, at the same time, the classical education system based on literature, philosophy, theology, philology and historiography was preserved. Practical science textbooks from Germany were in short supply here.

The difference in the book market in Germany and the UK was so big that it came to oddities. For example, the German professor of chemistry and pharmaceuticals Sigismund Hermbstädt published a book on tissue bleaching in 1806. Even in the absence of copyright, he received a greater fee than the English writer Mary Shelley from his bestselling novel Frankenstein, which is still published today.

Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, The

demand for technical literature in Germany was so great that publishers lacked authors and invited even less-than-gifted scholars to publish, so many German professors earned extra income from publishing information brochures and reference books on various topics.

According to Hoffner, the lack of copyright and the book publishing boom of that time led to a powerful industrial upsurge of the country, to the emergence in the 19th century of such industrial magnates as Alfred Krupp (at the end of the 19th century he owned the largest enterprise in Europe) and Werner von Siemens (founder of Siemens) .

The Krupp steel mill in Essen

The market for scientific literature has not collapsed even after the widespread introduction of copyright, which happened in Germany in the 1840s. However, German publishers went the British way: they increased prices and reduced the number of publications in paperbacks, to the displeasure of many authors.

For example, in 1843, German publishers published about 14,000 new books, most of which were scientific publications. If we take into account the number of population, then this is the same as it is published today, in the 21st century. For comparison, about 1,000 new works were published in the British Empire that year.

What is the reason for such a rapid economic and scientific development? Economic historian Eckhard Höffner believesthat the whole point is the lack of copyright.

Great Britain adopted copyright in 1710, and the largest German state, Prussia, only in 1837. At that time, Germany was divided into many lands and many years passed until the new concept became widespread.

Printing press in the 17th century. At that time there was no strict copyright even in England, and printers could plagiarize and print any kind of literature in any quantity. They also made large print runs of cheap publications for the mass market ..

Hoffner's economic work is the world's first serious scientific study on how copyright affects a country's development over a long time period. It is based on a direct comparison of two neighboring countries, and the conclusions reached have already caused an unhealthy liveliness in the academic environment. Until now, it was believed that copyright guarantees the prosperity of the book market. Like, authors get motivation to write only if they are fully confident in protecting their rights. History shows that this is not entirely true.

English publishers have tried to maximize the benefits of obtaining the right to an exclusive publication. They published a circulation of no more than 750 copies and sold it at maximum prices, the cost of the book often exceeded the weekly salary of an educated worker. Publishers made very good money on such a scheme. It is known that so far the first edition of the book in the premium version brings the lion's share of revenue to the publisher, while the next circulation in the paperback is sold at the cost of it. London publishers were limited to the first edition. Book buyers were wealthy aristocrats, wealthy and noble, and books were equated with elements of luxury. In a few libraries, the most valuable volumes were bolted to shelves in chains to protect against thieves.

In those same years, publishers and plagiarists operated in Germany who could cheaply reprint any book without fear of punishment. Book publishers made not only expensive publications for a wealthy public, but also cheap paperback books for the mass buyer. As a result, a book market has developed that is completely unlike the British. Bestsellers and scientific papers came out in Germany in huge print runs at extremely low prices, so that even in the farthest corners of the country, the poorest people could get a hold of books and make up a small library of pirated publications.

The presence of a huge readership encouraged scientists to publish the results of their work. According to Hoffner, an entirely new form of disseminating knowledge was born instead of the previously existing system of education at school or university or the transfer of knowledge from teacher to student.

Students throughout Germany received a host of the latest scientific treatises on chemistry, mechanics, engineering, optics and steel production. In England, at the same time, the classical education system based on literature, philosophy, theology, philology and historiography was preserved. Practical science textbooks from Germany were in short supply here.

The difference in the book market in Germany and the UK was so big that it came to oddities. For example, the German professor of chemistry and pharmaceuticals Sigismund Hermbstädt published a book on tissue bleaching in 1806. Even in the absence of copyright, he received a greater fee than the English writer Mary Shelley from his bestselling novel Frankenstein, which is still published today.

Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein, The

demand for technical literature in Germany was so great that publishers lacked authors and invited even less-than-gifted scholars to publish, so many German professors earned extra income from publishing information brochures and reference books on various topics.

According to Hoffner, the lack of copyright and the book publishing boom of that time led to a powerful industrial upsurge of the country, to the emergence in the 19th century of such industrial magnates as Alfred Krupp (at the end of the 19th century he owned the largest enterprise in Europe) and Werner von Siemens (founder of Siemens) .

The Krupp steel mill in Essen

The market for scientific literature has not collapsed even after the widespread introduction of copyright, which happened in Germany in the 1840s. However, German publishers went the British way: they increased prices and reduced the number of publications in paperbacks, to the displeasure of many authors.