What does boredom do to a man: the science of the wandering consciousness

- Transfer

“Every emotion has a goal from an evolutionary point of view,” says Sandy Mann, a psychologist and author of The Positive Side of Rest: Why Boredom Is Good [The Upside of Downtime: Why Boredom Is Good]. "I wanted to find out why we need such an emotion as boredom, seemingly negative and useless emotion."

So Mann began working in her specialty: boredom. Studying the emotions that appear in the workplace in the 1990s, she found that the second most often suppressed emotion after anger was - yes, yes - boredom. “They write bad things about her,” she says. “Almost everything is blamed for boredom.”

Immersed in the topic of boredom, Mann discovered that it is, in fact, "very interesting." And certainly not meaningless. Vizhnand van Tilburg of the University of Southampton explained the important evolutionary function of this disturbing and disgusting sensation: "Boredom makes people do things that they see more sense than the ones they have at their fingertips."

“Imagine a world in which we would not be bored,” says Mann. “We would constantly be pleased with anything — falling raindrops, cornflakes at breakfast.” Having dealt with the evolutionary sense of boredom, Mann wondered if she had any advantages other than a contribution to survival. “Instinctively,” she says, “I felt that everyone in life must be a bit bored.”

Mann developed an experiment in which a group of participants was given the most boring task she could come up with: copying phone numbers from the phone book manually. (If someone has never seen phone books in their lives, google them). The test was based on the classical verification of creativity, developed in 1967 by J. P. Guilford, an American psychologist, one of the first researchers of creativity. In the original test by Guilford “checking alternative uses”, the subject is given two minutes to come up with as many alternative ways of using everyday objects as possible - cups, paper clips, chairs. In the Mann version, she anticipated a test of creativity by a 20-minute meaningless task - copying phone numbers. After that, the subjects were asked to come up with as many ways as possible to use two paper cups. They gave a few ideas of average originality, such as flowerpots and sandbox toys.

In the next experiment, Mann boosted the boring part. Instead of copying numbers from the phone book, the subjects had to read the numbers out loud. And although some of them did it with pleasure, after which they were removed from the room, most of the participants considered this activity extremely, utterly boring. Getting into prostration is more difficult when you are busy with something active, like writing numbers, than when you are busy with such a passive act as reading. As a result, as Mann assumed, the subjects gave more creative ideas on the use of paper cups: earrings, telephones, musical instruments, and what she liked most was a Madonna-style bra. This group has already considered cups not only as containers.

With these experiments, Mann proved her point of view: bored people think more creatively than others.

But what happens during boredom that triggers your imagination? “Missing, we are looking for some kind of stimulus that is not in close proximity to us,” explains Mann. - Therefore, we begin to look for incentives, sending our consciousness to travel to various places that are in our heads. This is capable of stimulating creativity, because when you start dreaming and letting your mind wander, you go beyond the bounds of the conscious and go into the subconscious. This process allows you to create various links. And it's awesome. ”

Boredom opens the way to the wanderings of the mind, which helps our brain to create the very connections that can solve anything from planning a dinner to a breakthrough in the fight against global warming. Researchers have only recently begun to deal with the phenomenon of wandering consciousness, the activity that our brain does when it does something boring, or does nothing. Most of the research on dreams in reality was carried out over the past 10 years. With modern technologies of taking pictures of the brain, every day there are new discoveries of what our brain does not only when we are busy with something, but also when we are in prostration.

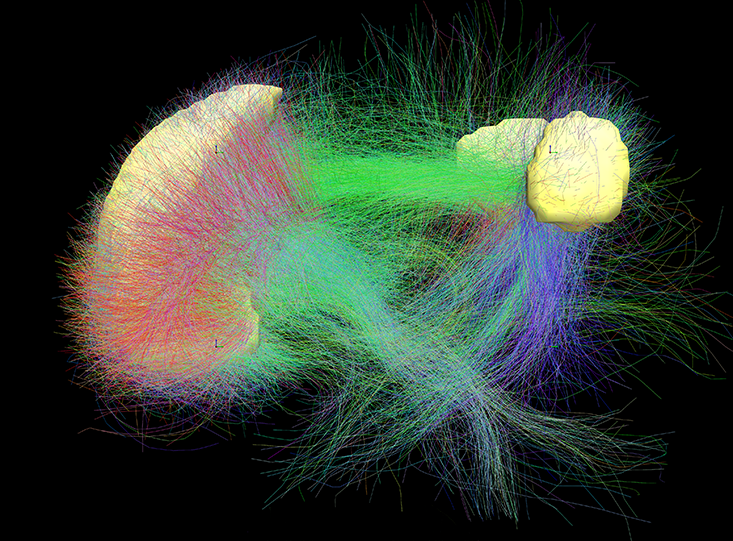

When we do something consciously - even if we write down numbers from the phone book - we use the “executive attention network] - the parts of the brain that control and suppress attention. As neuroscientist Markus Rachel says : “The attention network allows us to communicate directly with the world, here and now.” Conversely, when our mind wanders, we activate a part of the brain called the " network of the passive mode of the brain, " opened by Rachel. The passive mode of operation, so named Rachel, is used to describe the "resting brain"; that is, when we are not focused on an external task with clear goals. Therefore, unlike the generally accepted point of view, when we withdraw into ourselves, our mind does not turn off.

“From a scientific point of view, day-to-day dreams are an interesting phenomenon, because it determines the ability of people to create thoughts in a clean way, unlike thoughts that appear as a reaction to the events of the outside world,” says Jonathan Smallwood, who has studied mind wandering from the very beginning career neurobiologist, started 20 years ago. It may not have been a coincidence that he received his doctorate that year, when the passive brain mode was discovered.

Smallwood - so keen on wandering minds that he picked up a nickname with that name on Twitter- explained why this area is still not very developed. “She has an interesting place in the history of psychology and neuroscience because of how cognitive science is organized. In most of the experiments and theories, we demonstrate something to the brain and see what happens. " In the past, for the most part, this task-based method has been used to understand how the brain works, and it has generated a wealth of knowledge about how to adapt to external stimuli. “Mind wandering holds a special place, as it does not fit into this series of phenomena,” says Smallwood.

We are at a key point in the history of neuroscience, according to Smallwood, because with the advent of neuroimaging systems and other comprehensive tools for figuring out what is happening in the brain, we begin to understand the functioning that has eluded us. This includes our feelings during idleness.

The key role of dreams in reality became apparent to Smallwood as soon as he began to study it. Prostration is so important for us that “it can be the answer to the question that distinguishes us, humans, from less complex animals”. She participates in the work of a large number of skills, from creativity to predicting the future.

The network of the passive mode of the brain turns on when it is not concentrated on any task.

There is still so much to discover in this area, but what is already clear is that the passive mode does not mean the inaction of the brain. Smallwood uses functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study the nerve changes that occur when the test subjects lie in scanners and do nothing but consider a still image.

It turns out that in the passive mode, we use about 95% of the amount of energy that we spend with active thinking. Despite the lack of attention, our brain still does a lot of work. While people were lying in the scanners in the Smallwood experiment, their brains continued to "demonstrate very organized spontaneous activity."

“In principle, we do not understand why he is doing this,” he says. - When you have nothing to do, your thoughts do not stop. You continue to generate thoughts, even if you have nothing to do with them. ”

Smallwood and the team in particular are working to unite this state of unlimited arbitrary thoughts and the state of organized spontaneous brain activity, since they consider them to be “two sides of the same coin”.

The areas of the brain that make up the passive-mode network — the mid-temporal lobe, the mid-prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex — turn off when we switch to tasks that need attention. But they take a very active part in the work of autobiographical memory, models of the human psyche (in fact, our ability to represent what other people think and feel), and what is unique is the processing of an image of oneself, that is, the creation of a coherent view of oneself.

When we digress from the outside world and dive into ourselves, we do not turn off. We are connecting to a huge amount of memory, presenting future opportunities, analyzing our interaction with other people, reflecting on who we are. It seems that we are wasting time, looking at the longest red light in the world, waiting for it to switch to green, but our brain builds ideas and events in the right order.

This is the essence of the differences between the wandering of consciousness and other forms of the work of thought. Instead of feeling, sorting and understanding things based on how they come to us from the outside, we do it within our own cognitive system. This gives us the opportunity to think and better understand everything after the urgency of the moment has passed. Smallwood gives the argument as an example: while the argument is going on, it is difficult to be objective or to look at everything from the point of view of another person. Anger, adrenaline, the physical and emotional presence of another person interfere with the analysis. But in the shower or at the wheel the next day, when your brain experiences what has happened, your thoughts become deeper. You not only think about a million variants of your answers, but, possibly, without “the stimulus that is the person with whom you argued”, you can look at everything from a different point of view and generate some ideas. Reflections about interpersonal interaction in a different way than what happens during a meeting in the real world are an excellent form of creativity, stimulated by the wandering mind.

“Daydreaming dreams are especially important for a species like us, with a high importance of social interaction,” Smallwood says. “All because the most unpredictable phenomenon in your daily life will be other people.” Our world, from traffic lights to cash desks in grocery stores, works according to a simple set of rules. Unlike people. “Dreams in reality reflect the need to understand the complex aspects of life that are almost always associated with other people.”

After talking with Professor Smallwood, I was even more convinced that filling in the free minutes of the day with email checks, Twitter updates or continuous phone checks is destructive. I understood why the willingness to let go of my mind to wander a little is the key to creativity and productivity.

“Well, this is a controversial statement,” said Smallwood. “People whose mind is always in prostration cannot do anything at all.”

Really. I didn’t like that Smallwood was holding back my enthusiasm, but waking dreams in reality were not always considered useful. Freud considered people with detached consciousness to be neurotic. Back in the 1960s, teachers were told that dreamer students were at risk of acquiring psychological health problems.

Obviously, there are different ways to dream in reality - and not all of them are productive or positive. In the book The Inner World of Daydreaming, which contains fruitful ideas, psychologist Jerome Singer, who has been studying the wandering mind for more than 50 years, identifies three different dream styles:

- Uncontrollable attention.

- Dysphoric prostration with guilt syndrome.

- Positive constructive prostration.

Their names speak for themselves. People who are poorly able to manage their attention, are easily excited, easily distracted, it is difficult for them to concentrate even on their dreams in reality. When our wandering mind becomes dysphoric, our thoughts become counterproductive and negative. We scold ourselves for having forgotten someone's birthday, or for not being able to fight back someone at the right moment. We are overwhelmed by such emotions as guilt, anxiety and anger. Some people easily get stuck in this circle of negative thinking. It is not surprising that this kind of mind wandering is more common in people who complain of a chronic level of unhappiness.

When dysphoric prostration turns into chronic, people may tend to destructive behavior - depending on gambling, chemicals or food. The only question is how thoughts wander in people complaining about a chronic level of unhappiness - it just manifests itself more often, or else it contributes to a worsening of mood. In a 2010 study, “Mind Wandering - Unhappy Mind,” Harvard psychologists Matthew Killingworth and Daniel Gilbert developed an iPhone app designed to monitor the thoughts, feelings, and actions of 5,000 people at any given time during the day. The application beeped at random times, and the subject answered questions that affected his actions, thoughts about these actions, the level of happiness, and other things.

This can be heard in any class in yoga - the key to happiness lies in living in the current moment. So how is it in reality? Is wandering mind productive or destroying itself? Apparently, like everything in this life, dreams come true - a complicated and many-sided thing.

Smallwood participated in a study of the relationship between mood and mind wandering, from which it was concluded that "the generation of thoughts that are not related to the current environment can be both a cause and a consequence of unhappiness." I'm sorry, what!?

A 2013 study (Florence JM Ruby, Haakon Engen, Tania Singer) states that not all types of detached reflections or dreams in reality are the same. The data collected from hundreds of participants showed whether their thoughts were related to the current task, whether they focused on the past or the future, whether they were thinking of themselves or others in a positive or negative way. The study found that negative thoughts caused a negative mood (of course). Depressed thoughts of people in depression were both the cause and effect of negative moods, and "thoughts associated with the past are particularly likely to be associated with a bad mood." But there is still hope - the study also found that "thoughts associated with the future and with oneself preceded mood improvements, even if the current thoughts were negative."

“Dream dreams have features that allow us to think about our lives in an unusual way,” Smallwood told me. “But in certain situations, you probably shouldn't keep thinking about the same thing.” Many of the states of chronic unhappiness are probably related to the wandering of the mind simply because these problems cannot be solved. ”

Dreams in reality are similar to smartphones with the fact that it is easy to overdo it with such a pastime. Smallwood argues that we don’t need to think about how our phones or our brains work in terms of "good" or "bad." The thing is how we use them. “Smartphones allow us to do amazing things - for example, to communicate with people who are at a great distance, but we can fall into the trap by dedicating our whole lives to them,” he says. “And this is not the fault of smartphones.” Dreams in reality allow us to take a different look at things - whether it is good or bad, but, most importantly, differently.

The reverse side of dysphoric prostration, a positively constructive variety, occurs when our thoughts take a creative direction. We are starting to rejoice at the possibilities that our brain can mentally evoke almost nowhere, as if by magic. This mode of mind wandering reflects our inner desire to explore ideas and feelings, plan, solve problems.

How to engage in healthy wandering mind? Let's say you quarreled with a colleague. In the evening, when you cut a salad for yourself, you find that you constantly lose this scene in your head over and over again. Waves of anger roll over you, and you scold yourself for not having come up with some smarter response to his unwarranted claim that you did not invest in the last project at 100%. By applying positive and constructive abstract thinking, you say goodbye to the past and come up with a way to show him how much you actually have to work for your joint projects. Or you decide to move to another team and no longer communicate with this goat, because life is too short.

“Changing the mindset is harder than talking about it,” said Smallwood. “Dreams in reality are different from other forms of distraction because when your thoughts come up against certain topics, it shows how you are in your life and how you feel about it.” The problem is that sometimes, when a person’s life does not turn out very well, it becomes more difficult to dream in reality than when life seems easy. In any case, the point is that this pastime gives us the opportunity to understand who we are. ”

All these hours as a young mom that I spent rolling my child in a stroller, because he could not fall asleep because of colic and worried that I could be more productive or stay in touch with society and what it does actually turned out to be surprisingly useful - I unintentionally gave my mind free space and time so that it could reach previously inaccessible latitudes. I not only connected to the past experience, but also imagined myself in the future in different places, conceived by me, and was engaged in life planning.

And if chewing on an unpleasant experience or constantly returning to the past with thoughts is definitely a by-product of mind wanderings, studies by Smallwood and others have shown that after a sufficient amount of time for self-contemplation, our mind begins to lean toward "perspective thinking." Such thoughts help us to find new solutions - for example, in my case it was a completely new career. Dreams in reality by their nature help us when we are confronted with a difficult task of a personal or professional nature. And boredom is one of the best catalysts for starting this process.

At first glance, boredom and insight are opposite to each other. Boredom, if defined only as a state of fatigue and anxiety without signs of interest, has only negative connotations, and it must be avoided by all means; we strive for discernment, and it represents the quality of bright success and unusual mental abilities. Genius, intellect, talent, lightness against apathy, stupidity, despondency. This is not obvious, but these two opposite states are very closely related.

Andreas Elpidorow, a researcher at the psychological department of the University of Louisville, and, as he calls himself, a defender of boredom, explains: "Boredom motivates the pursuit of new goals when current goals are no longer satisfactory, attractive or meaningful for you." In his 2014 scientific article, The Bright Side of Boredom, Elpidorou argues that boredom “plays the role of a regulatory state that supports a person in fulfilling his goals. In the absence of boredom, a person would have been captured by unsatisfactory situations and would have missed a lot of experience that was pleasant in terms of emotions, reason and social intercourse. Boredom is both a warning that we are not doing what we want, and a push that motivates us to switch goals and projects. ”

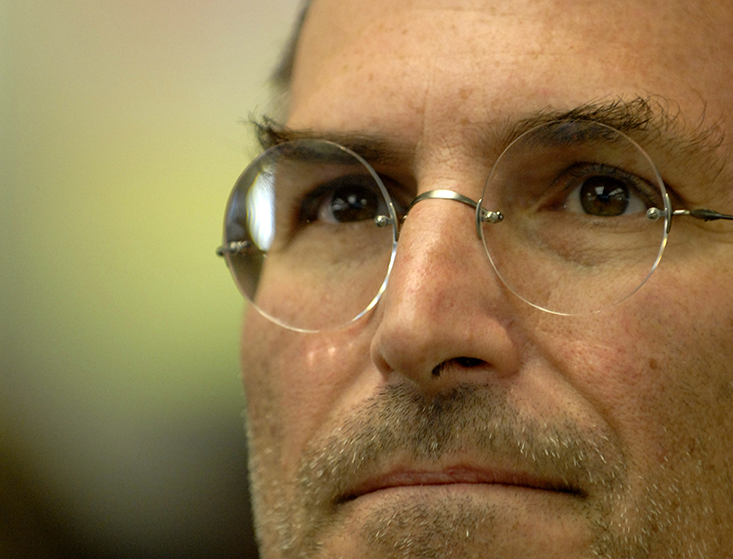

Boredom can be said to be an insight incubator. This is a disorderly, unpleasant, confusing, despairing place in which you have to spend a little time before you come up with a successful formula or equation. This idea has been repeated many times. The Hobbit was conceived when J.R.R. Tolkien, an Oxford professor, "received a huge mountain of examination papers and gave them marks in the summer, which was very difficult, and, unfortunately, also boring." When he came across a clean-sheet student’s work, he was delighted. “Amazing! There is nothing to read, ”the Air Force told Tolkien in 1968. “So I don’t know why, I sketched on it:“ In the hole there lived a hobbit in the ground ”. So the first line of one of the most beloved fantasy books was born. The statement of Steve Jobs who changed the world with his technological ideas is well known: “I truly believe in boredom. Technological things are great, but when you have nothing to do, it can also be beautiful. ” Stephen Levy, co-founder of Apple, wrote in Wired magazine, as he nostalgically recalls the long, boring summer months of his youth, feeding his curiosity, because “everything else grows out of curiosity,” and expressed concern about the erosion of boredom emanating from devices that he helped create.

Steve Jobs was a master of insight. So use his advice happily to welcome boredom. Give your knowledge of the science and history of boredom to inspire you to bring boredom back into your life. At first, it will seem uncomfortable, annoying, you may even get angry, but who knows what you can achieve when you overcome the first phases of boredom and its amazing side effects start to turn on?

From the book Manush Zomorodi "Bored and insightful" [Bored and Brilliant], 2017.