Part 4. A graph model for calculating logical functions for asynchronous parallel processes

We proceed to the calculation of logical functions according to the graph for a wider class of behaviors. We consider cyclic autonomous behaviors that do not contain multiple signals (or in another way: do not contain indexed events). Another limitation: for convenience, we will not consider the connection of parallel branches in OR. We consider only a connection by AND, that is, an event is triggered only when all its predecessor events are triggered.

We will use STG to describe the behavior, but with additional restrictions. For each place, the number of arcs entering and leaving it is strictly equal to one each. Accordingly, a place with incoming and outgoing arcs can be considered as one arc connecting two events (transitions). Accordingly, the marking moves along arcs. Since behaviors with multiple signals are not considered now, event indices are prohibited, they are not needed. Empty events are prohibited. The situation is also forbidden when two arcs included in one event come out of events that are not parallel to each other (a special case is from the same event). The purpose of this is to get rid of arcs that do not carry a semantic load. The rest is considered correct (normal, live, safe) from the point of view of STG behavior, taking into account the above limitations.

Definition 1. The event into which the arc enters is a consequence of the event from which this arc exits. Conversely, the event from which the arc exits is the cause of the event into which this arc enters.

Definition 2. A path - an endless sequence of events - the result of changes in the labeling of a graph, starting with a specific one. Each event enters the sequence an infinite number of times. Each such entry is unique.

Definition 3. The trace of event A is the path in which all events are either the direct consequence of event A, or the result of the transitive closure of the relationship of the consequence of events with respect to event A. The initial marking for the trace of event A is established as follows. If the marking is arbitrarily changed, after event A is triggered, the markers in the output arcs of event A are fixed. Then the rest of the markers move until the movement of the markers becomes impossible without releasing the markers in the output arcs of event A. The resulting marking is the initial marking for the trace of event A.

Definition 4. We introduce the ordering relation for three events (A, B, C). Three events are ordered (written A> B> C) if and only if, for any trace of event A, the first occurrence of event B in the sequence will always occur earlier than the first occurrence of event C.

Remark. Event A can be parallel to both events B and C (or only C), or both events A and B can be parallel to event C.

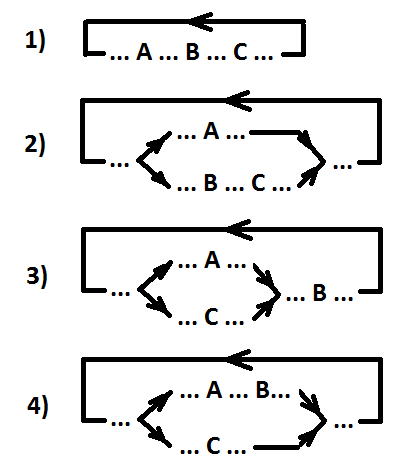

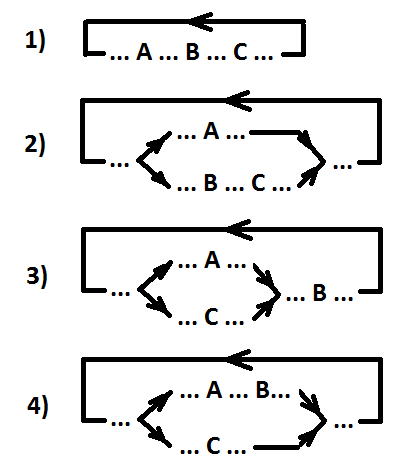

Variants of arrangement of ordered events A, B and C (A> B> C).

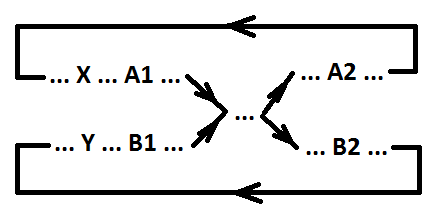

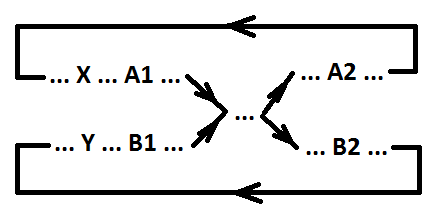

Definition 5. Signal b (switching B1 and B2) picks up signal a (switching A1 and A2) with respect to events X and Y (events X and Y are parallel or coincide) if the following conditions are satisfied:

1) X> A1> A2;

2) if event A2 is parallel to event X and not parallel to event Y, then X>

3) Y> B1> B2;

4) if event B2 is parallel to event Y and not parallel to event X, then Y> B2> X;

5) Y> B1> A2;

6) if event A2 is parallel to event Y and not parallel to event X, then Y> A2> X.

Remark 1. Conditions 1, 2, and 3, 4 determine the ordering of the switching of signals a and b, respectively. Conditions 5, 6 specify the ordering of the catch event B1 and the catch event A2.

Remark 2. Event X can be event A1. In this case, conditions 1 and 2 degenerate.

Remark 3. Event Y can be event B1. In this case, conditions 3, 4, and 5 degenerate.

Remark 4. Event X can be event A1, and also event B1 can be event Y. In this case, conditions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 degenerate.

Now we begin to consider what an implant is. The implicant is characterized by events, as a result of which the implicant changes its meaning.

Definition 6. An event, as a result of which the implicant AND (OR) changes its value from 1 (0) to 0 (1), we will call the right boundary of the implicant. The signal corresponding to this event will be called switching on. The implicant turns on.

Definition 7. An event, as a result of which the implicant AND (OR) changes its value from 0 (1) to 1 (0), we will call the left border of the implicant. The signal corresponding to this event will be called off. The implicant turns off.

Definition 8. An implicant in which any two right (or any two left) boundaries are not parallel to each other will be called discontinuous.

For now, we will not consider interrupted implants. We will return to their consideration below.

So, we have: all the right borders of the implicants are pairwise parallel to each other, as well as the left borders of the implicants are pairwise parallel to each other.

An important property. The implicant turns on when at least one event occurs, which is the right border of the implicant. The implicant turns off only when all events that are the left boundaries of the implicant occur.

Now it remains to identify the properties of the signals forming the implant.

Definition 9. The signal included in the implant will be called a variable.

The first property of variables. Turning on and off signals are variable.

The second property of variables. For any switching variable (one of whose switches is the left border of the implicant L, the other is some event X), there must be an event - some right border R of the same implicant is such that either X and R are the same event, or R > X> L.

The third property of variables. For any inclusive variable (one of whose switches is the right border of the implicant R, the other is some event X), there must be an event - some left border L of the same implicant is such that either X and L are the same event, or R > X> L.

The fourth property of variables. For any variable (switching X1 and X2) that is not turning on or off, there must be two events: some left border of the implicant L and some right border of the implicant R such that R> X1> L and R> X2> L . Otherwise, the implicant could not maintain a constant value in the off position.

The fifth property of variables. For any pair: some switching variable and some switching variable, there must be a sequence of variables picking up each other relative to some right borders of the implicant (for different pickups, the right borders may vary), starting with this switching variable and ending with this switching variable . Otherwise, the implicant could not maintain a constant value in the on position.

Sixth property of variables. For any inclusive variable a, if the right boundary of the implicant is the event a + (a-), then such a variable is included in the record of the implicant AND (OR) with inversion, and in the record of the implicant OR (AND) without inversion. For any switching variable a, if the left border of the implicant is the event a- (a +), then such a variable a is included in the record of the implicant AND (OR) with inversion, and in the record of the implicant OR (AND) without inversion.

The seventh property of variables. By virtue of the fourth property of variables, for every variable a that is not turning on or off, there is a right boundary for the implicants R and a left border for the implicants L such that R> a +> L and R> a-> L. If R> a +> a-, then such a variable enters the implicant of And with inversion, and the implicant of OR without inversion. If R> a-> a +, then such a variable enters the implicant AND without inversion, and the implicant OR with inversion.

The seven listed properties of variables are necessary properties of the implicant. Also, these properties are sufficient to describe the implants.

Comment. The above description of the implant does not prohibit the situation when some left border of the implant can be parallel to some right border of the same implicant. The meaning of this phenomenon is that, depending on the speed of parallel processes, such an implant in real time may not be necessary for the implementation of the corresponding signal and in real time it may not turn off (if the right boundary works earlier than the left boundary).

Now we will consider how the normal form of a logical function is built from the implicant.

Definition 10. If for some state the implicant is in the off position (the value of the implant AND (OR) is 1 (0)), we say that the implicant covers this state.

Consider a certain signal x, for which we need to calculate a logical function. To construct a DNF (CNF), it is necessary to AND (OR) -implicants cover all the states at which the function x is 1 (0). In this case, it is necessary that none of these AND (OR) -implicants cover states in which the function x is 0 (1). Also, when calculating logical functions, it is necessary to take into account the specifics of circuitry: implicants should “overlap”. That is, if in some state the implicant can turn on (that is, an event can be triggered that is the right boundary of this implicant) and the value of the signal function x does not change during this switching, then there must be another implicant that covers this state and does not turn on when this event is triggered.

Now we need to clarify three questions. What is a state in terms of a graph? How to determine the states at which the signal function x is 1 (0)? How to determine the conditions that the implant covers?

Let's start with the states. Any achievable labeling is a condition. Since there are no CSC conflicts, each achievable label corresponds to a unique state (achievable). In unattainable states, the value of the function is arbitrary and there is no need to consider them. Thus, each state that we consider is uniquely described by the corresponding labeling. The position of each marker is uniquely determined by the arc that it marks. Each arc is uniquely associated with a pair of (ordered) events: the event from which the arc exits and the event into which the arc enters. Thus, any attainable state is uniquely described by a set consisting of ordered pairs of events.

Definition 11. A pair of events denoting a marked arc will be written {P, S}, where P is the cause event, and S is the consequence event.

Definition 12. MM will be called the set of ordered pairs {P, S}, which describes some attainable state.

Now let us determine for which states the value of the function x is 1, and for which it is 0. Let the events x + be caused by n events A1, A2, ..., An, and the events x- caused by m events B1, B2, ..., Bm.

The value of the function x is 1 if:

either 1) for each i from 1 to n, the pair {Ai, x +} belongs to the set MM;

or 2) a pair {x +, S} such that x +> S> x- belongs to the set MM;

or 3) a pair {P, S} such that x +> P> x- and x +> S> x- belongs to the set MM;

or 4) a pair {P, x-} such that x +> P> x- belongs to the set MM and there exists i from 1 to m such that the pair {Bi, x-} does not belong to the set MM.

The value of the function x is 0 if:

either 1) for each i from 1 to m, the pair {Bi, x-} belongs to the set MM;

or 2) a pair {x-, S} such that x-> S> x + belongs to the set MM;

or 3) a pair {P, S} such that x-> P> x + and x-> S> x + belongs to the set MM;

or 4) a pair {P, x +} such that x-> P> x + belongs to the set MM and there exists i from 1 to n such that the pair {Ai, x +} does not belong to the set MM.

Now we find out what conditions the implant covers. Let the implicant have n left boundaries L1, L2, ..., Ln and m right boundaries R1, R2, ..., Rm.

The implicant does not cover the state described by the set MM if at least one of the pairs {P, S} belonging to the set MM satisfies the following condition: there exist i from 1 to n and j from 1 to m such that

1) Li and S is the same event and Rj> P> Li,

either 2) Rj and P is the same event and Rj> S> Li,

or 3) Rj> P> Li and Rj> S> Li.

This statement is true by virtue of the fifth property of variables.

The implicant covers the state described by the set MM if for none of the pairs {P, S} belonging to the set MM the following condition is satisfied: there exist i from 1 to n and j from 1 to m such that

1) Li and S this is the same event and Rj> P> Li,

either 2) Rj and P is the same event and Rj> S> Li,

or 3) Rj> P> Li and Rj>

This statement is true by virtue of the second, third, and fourth properties of variables.

Figuratively speaking, an implicant covers the state if all markers are between the left and right boundaries of the implicant. If at least one marker is located outside these boundaries, then the implant does not cover this state.

Now we have a tool for calculating normal forms (it is still not clear, however, there is still a question with intermittent implants). But we are interested in minimal normal forms (taking into account the specifics of circuitry). Before proceeding further, let us return to the consideration of intermittent implicants. Consider the I-implicant for DNF signal x (the case with the OR-implicant for CNF is similar). Suppose that the two left boundaries of the same implicants L1 and L2 are not parallel to each other and L1> L2> x- (the case for two right boundaries is considered similarly). Then there must be two right boundaries of the implicants R1 and R2 such that for pairs of both L1 and R2, and L2 and R1, the second, third, fourth and fifth properties of the variables must be satisfied. If there is a left boundary L3 parallel to L1, then for the pair L3 and R2 the above properties must also be fulfilled (similarly, in the case of the existence of corresponding boundaries of the implicants that are parallel to the boundaries of L2, R1 and R2). But, since multiple signals are not used, there must be a non-discontinuous implicant with boundaries L1 and R2 (and with parallel corresponding boundaries, if any of the interrupted implicants had them). In this case, the non-discontinuous implicant consists of fewer variables and covers all states covered by the discontinuous implicant, on which the value of the signal function x is 1. Hence the conclusion: discontinuous implicants are not extremals and they cannot be used to calculate minimal functions. there must be a non-discontinuous implicant with boundaries L1 and R2 (and with parallel corresponding boundaries, if any of the interrupted implicants had them). In this case, the non-discontinuous implicant consists of fewer variables and covers all states covered by the discontinuous implicant, on which the value of the signal function x is 1. Hence the conclusion: discontinuous implicants are not extremals and they cannot be used to calculate minimal functions. there must be a non-discontinuous implicant with boundaries L1 and R2 (and with parallel corresponding boundaries, if any of the interrupted implicants had them). In this case, the non-discontinuous implicant consists of fewer variables and covers all states covered by the discontinuous implicant, on which the value of the signal function x is 1. Hence the conclusion: discontinuous implicants are not extremals and they cannot be used to calculate minimal functions.

More on calculating minimal functions in the next part.

We will use STG to describe the behavior, but with additional restrictions. For each place, the number of arcs entering and leaving it is strictly equal to one each. Accordingly, a place with incoming and outgoing arcs can be considered as one arc connecting two events (transitions). Accordingly, the marking moves along arcs. Since behaviors with multiple signals are not considered now, event indices are prohibited, they are not needed. Empty events are prohibited. The situation is also forbidden when two arcs included in one event come out of events that are not parallel to each other (a special case is from the same event). The purpose of this is to get rid of arcs that do not carry a semantic load. The rest is considered correct (normal, live, safe) from the point of view of STG behavior, taking into account the above limitations.

Definition 1. The event into which the arc enters is a consequence of the event from which this arc exits. Conversely, the event from which the arc exits is the cause of the event into which this arc enters.

Definition 2. A path - an endless sequence of events - the result of changes in the labeling of a graph, starting with a specific one. Each event enters the sequence an infinite number of times. Each such entry is unique.

Definition 3. The trace of event A is the path in which all events are either the direct consequence of event A, or the result of the transitive closure of the relationship of the consequence of events with respect to event A. The initial marking for the trace of event A is established as follows. If the marking is arbitrarily changed, after event A is triggered, the markers in the output arcs of event A are fixed. Then the rest of the markers move until the movement of the markers becomes impossible without releasing the markers in the output arcs of event A. The resulting marking is the initial marking for the trace of event A.

Definition 4. We introduce the ordering relation for three events (A, B, C). Three events are ordered (written A> B> C) if and only if, for any trace of event A, the first occurrence of event B in the sequence will always occur earlier than the first occurrence of event C.

Remark. Event A can be parallel to both events B and C (or only C), or both events A and B can be parallel to event C.

Variants of arrangement of ordered events A, B and C (A> B> C).

Definition 5. Signal b (switching B1 and B2) picks up signal a (switching A1 and A2) with respect to events X and Y (events X and Y are parallel or coincide) if the following conditions are satisfied:

1) X> A1> A2;

2) if event A2 is parallel to event X and not parallel to event Y, then X>

3) Y> B1> B2;

4) if event B2 is parallel to event Y and not parallel to event X, then Y> B2> X;

5) Y> B1> A2;

6) if event A2 is parallel to event Y and not parallel to event X, then Y> A2> X.

Remark 1. Conditions 1, 2, and 3, 4 determine the ordering of the switching of signals a and b, respectively. Conditions 5, 6 specify the ordering of the catch event B1 and the catch event A2.

Remark 2. Event X can be event A1. In this case, conditions 1 and 2 degenerate.

Remark 3. Event Y can be event B1. In this case, conditions 3, 4, and 5 degenerate.

Remark 4. Event X can be event A1, and also event B1 can be event Y. In this case, conditions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 degenerate.

Now we begin to consider what an implant is. The implicant is characterized by events, as a result of which the implicant changes its meaning.

Definition 6. An event, as a result of which the implicant AND (OR) changes its value from 1 (0) to 0 (1), we will call the right boundary of the implicant. The signal corresponding to this event will be called switching on. The implicant turns on.

Definition 7. An event, as a result of which the implicant AND (OR) changes its value from 0 (1) to 1 (0), we will call the left border of the implicant. The signal corresponding to this event will be called off. The implicant turns off.

Definition 8. An implicant in which any two right (or any two left) boundaries are not parallel to each other will be called discontinuous.

For now, we will not consider interrupted implants. We will return to their consideration below.

So, we have: all the right borders of the implicants are pairwise parallel to each other, as well as the left borders of the implicants are pairwise parallel to each other.

An important property. The implicant turns on when at least one event occurs, which is the right border of the implicant. The implicant turns off only when all events that are the left boundaries of the implicant occur.

Now it remains to identify the properties of the signals forming the implant.

Definition 9. The signal included in the implant will be called a variable.

The first property of variables. Turning on and off signals are variable.

The second property of variables. For any switching variable (one of whose switches is the left border of the implicant L, the other is some event X), there must be an event - some right border R of the same implicant is such that either X and R are the same event, or R > X> L.

The third property of variables. For any inclusive variable (one of whose switches is the right border of the implicant R, the other is some event X), there must be an event - some left border L of the same implicant is such that either X and L are the same event, or R > X> L.

The fourth property of variables. For any variable (switching X1 and X2) that is not turning on or off, there must be two events: some left border of the implicant L and some right border of the implicant R such that R> X1> L and R> X2> L . Otherwise, the implicant could not maintain a constant value in the off position.

The fifth property of variables. For any pair: some switching variable and some switching variable, there must be a sequence of variables picking up each other relative to some right borders of the implicant (for different pickups, the right borders may vary), starting with this switching variable and ending with this switching variable . Otherwise, the implicant could not maintain a constant value in the on position.

Sixth property of variables. For any inclusive variable a, if the right boundary of the implicant is the event a + (a-), then such a variable is included in the record of the implicant AND (OR) with inversion, and in the record of the implicant OR (AND) without inversion. For any switching variable a, if the left border of the implicant is the event a- (a +), then such a variable a is included in the record of the implicant AND (OR) with inversion, and in the record of the implicant OR (AND) without inversion.

The seventh property of variables. By virtue of the fourth property of variables, for every variable a that is not turning on or off, there is a right boundary for the implicants R and a left border for the implicants L such that R> a +> L and R> a-> L. If R> a +> a-, then such a variable enters the implicant of And with inversion, and the implicant of OR without inversion. If R> a-> a +, then such a variable enters the implicant AND without inversion, and the implicant OR with inversion.

The seven listed properties of variables are necessary properties of the implicant. Also, these properties are sufficient to describe the implants.

Comment. The above description of the implant does not prohibit the situation when some left border of the implant can be parallel to some right border of the same implicant. The meaning of this phenomenon is that, depending on the speed of parallel processes, such an implant in real time may not be necessary for the implementation of the corresponding signal and in real time it may not turn off (if the right boundary works earlier than the left boundary).

Now we will consider how the normal form of a logical function is built from the implicant.

Definition 10. If for some state the implicant is in the off position (the value of the implant AND (OR) is 1 (0)), we say that the implicant covers this state.

Consider a certain signal x, for which we need to calculate a logical function. To construct a DNF (CNF), it is necessary to AND (OR) -implicants cover all the states at which the function x is 1 (0). In this case, it is necessary that none of these AND (OR) -implicants cover states in which the function x is 0 (1). Also, when calculating logical functions, it is necessary to take into account the specifics of circuitry: implicants should “overlap”. That is, if in some state the implicant can turn on (that is, an event can be triggered that is the right boundary of this implicant) and the value of the signal function x does not change during this switching, then there must be another implicant that covers this state and does not turn on when this event is triggered.

Now we need to clarify three questions. What is a state in terms of a graph? How to determine the states at which the signal function x is 1 (0)? How to determine the conditions that the implant covers?

Let's start with the states. Any achievable labeling is a condition. Since there are no CSC conflicts, each achievable label corresponds to a unique state (achievable). In unattainable states, the value of the function is arbitrary and there is no need to consider them. Thus, each state that we consider is uniquely described by the corresponding labeling. The position of each marker is uniquely determined by the arc that it marks. Each arc is uniquely associated with a pair of (ordered) events: the event from which the arc exits and the event into which the arc enters. Thus, any attainable state is uniquely described by a set consisting of ordered pairs of events.

Definition 11. A pair of events denoting a marked arc will be written {P, S}, where P is the cause event, and S is the consequence event.

Definition 12. MM will be called the set of ordered pairs {P, S}, which describes some attainable state.

Now let us determine for which states the value of the function x is 1, and for which it is 0. Let the events x + be caused by n events A1, A2, ..., An, and the events x- caused by m events B1, B2, ..., Bm.

The value of the function x is 1 if:

either 1) for each i from 1 to n, the pair {Ai, x +} belongs to the set MM;

or 2) a pair {x +, S} such that x +> S> x- belongs to the set MM;

or 3) a pair {P, S} such that x +> P> x- and x +> S> x- belongs to the set MM;

or 4) a pair {P, x-} such that x +> P> x- belongs to the set MM and there exists i from 1 to m such that the pair {Bi, x-} does not belong to the set MM.

The value of the function x is 0 if:

either 1) for each i from 1 to m, the pair {Bi, x-} belongs to the set MM;

or 2) a pair {x-, S} such that x-> S> x + belongs to the set MM;

or 3) a pair {P, S} such that x-> P> x + and x-> S> x + belongs to the set MM;

or 4) a pair {P, x +} such that x-> P> x + belongs to the set MM and there exists i from 1 to n such that the pair {Ai, x +} does not belong to the set MM.

Now we find out what conditions the implant covers. Let the implicant have n left boundaries L1, L2, ..., Ln and m right boundaries R1, R2, ..., Rm.

The implicant does not cover the state described by the set MM if at least one of the pairs {P, S} belonging to the set MM satisfies the following condition: there exist i from 1 to n and j from 1 to m such that

1) Li and S is the same event and Rj> P> Li,

either 2) Rj and P is the same event and Rj> S> Li,

or 3) Rj> P> Li and Rj> S> Li.

This statement is true by virtue of the fifth property of variables.

The implicant covers the state described by the set MM if for none of the pairs {P, S} belonging to the set MM the following condition is satisfied: there exist i from 1 to n and j from 1 to m such that

1) Li and S this is the same event and Rj> P> Li,

either 2) Rj and P is the same event and Rj> S> Li,

or 3) Rj> P> Li and Rj>

This statement is true by virtue of the second, third, and fourth properties of variables.

Figuratively speaking, an implicant covers the state if all markers are between the left and right boundaries of the implicant. If at least one marker is located outside these boundaries, then the implant does not cover this state.

Now we have a tool for calculating normal forms (it is still not clear, however, there is still a question with intermittent implants). But we are interested in minimal normal forms (taking into account the specifics of circuitry). Before proceeding further, let us return to the consideration of intermittent implicants. Consider the I-implicant for DNF signal x (the case with the OR-implicant for CNF is similar). Suppose that the two left boundaries of the same implicants L1 and L2 are not parallel to each other and L1> L2> x- (the case for two right boundaries is considered similarly). Then there must be two right boundaries of the implicants R1 and R2 such that for pairs of both L1 and R2, and L2 and R1, the second, third, fourth and fifth properties of the variables must be satisfied. If there is a left boundary L3 parallel to L1, then for the pair L3 and R2 the above properties must also be fulfilled (similarly, in the case of the existence of corresponding boundaries of the implicants that are parallel to the boundaries of L2, R1 and R2). But, since multiple signals are not used, there must be a non-discontinuous implicant with boundaries L1 and R2 (and with parallel corresponding boundaries, if any of the interrupted implicants had them). In this case, the non-discontinuous implicant consists of fewer variables and covers all states covered by the discontinuous implicant, on which the value of the signal function x is 1. Hence the conclusion: discontinuous implicants are not extremals and they cannot be used to calculate minimal functions. there must be a non-discontinuous implicant with boundaries L1 and R2 (and with parallel corresponding boundaries, if any of the interrupted implicants had them). In this case, the non-discontinuous implicant consists of fewer variables and covers all states covered by the discontinuous implicant, on which the value of the signal function x is 1. Hence the conclusion: discontinuous implicants are not extremals and they cannot be used to calculate minimal functions. there must be a non-discontinuous implicant with boundaries L1 and R2 (and with parallel corresponding boundaries, if any of the interrupted implicants had them). In this case, the non-discontinuous implicant consists of fewer variables and covers all states covered by the discontinuous implicant, on which the value of the signal function x is 1. Hence the conclusion: discontinuous implicants are not extremals and they cannot be used to calculate minimal functions.

More on calculating minimal functions in the next part.