Mental models in information security

- Transfer

I previously argued why information security is in a state of cognitive crisis , and the situation is getting worse. Despite the abundance of freely available information, we do not cope well with identifying and training practical skills in the field of information security, in the whole variety of available specialties. Most of the new specialists are mostly self-taught, and universities are not able to let out specialists ready for work.

The situation is not unique to our profession. Similar problems were previously encountered by medicine, law, accounting and other areas. Using their example, one can identify several signs that determine the cognitive crisis:

Demand for specialists significantly exceeds supply. For experienced professionals, there are a huge number of vacancies. Since many organizations need experience, they are not able to invest properly in the training of their employees. The deficit greatly inflates the salaries of practitioners with relevant skills, and hyperspecialization occurs.

Most of the information is unreliable and unverifiable . There are few authoritative sources of knowledge about critical components and procedures. Practitioners rely heavily on personal experience and observations that are unverified and objectively unverified. This makes it difficult to reliably learn new information and makes it even more difficult to develop best practices and measure success.

Major industry problems persist that cannot be resolved systematically. The industry is not able to organize or effectively deal with the biggest problems that it faces. In medicine, these are epidemics and crises, in accounting, large-scale uncontrolled thefts through falsification of reporting. And the worms of the 2000s are still rampant on computer networks: there are hundreds of thousands of hosts with vulnerable SMB ports on the Internet, and there are no signs that the crypto ransomware epidemic is on the decline. Many of the main problems that we faced twenty years ago have survived or become even worse.

As other areas emerged from the cognitive crisis more formalized and effective, information security has hope. We can learn from them and make our own cognitive revolution . Three things must happen:

As other areas emerged from the cognitive crisis more formalized and effective, information security has hope. We can learn from them and make our own cognitive revolution . Three things must happen:

At the center of all three pillars of the cognitive revolution is the concept of the mental model.

The mental model is just a way of looking at the world. We are surrounded by complex systems, so the brain creates models to simplify.

You use mental models all the time. Here are a few examples:

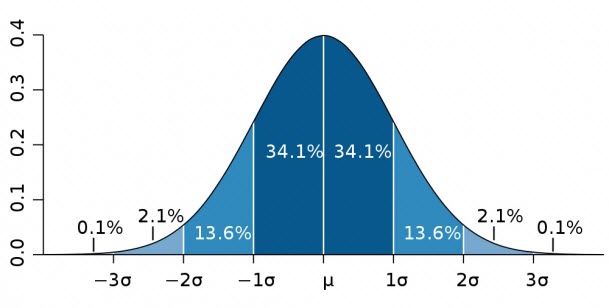

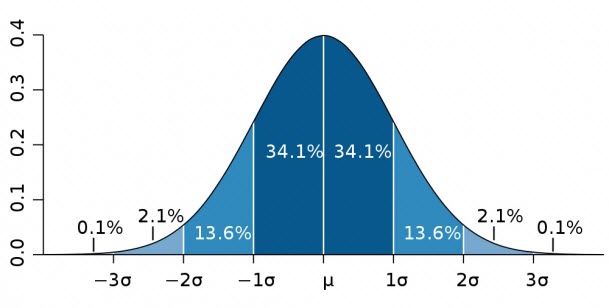

Distribution and bell-shaped curve . In normally distributed data, most points are grouped around the middle. Thus, most people have medium intelligence, and only a few are extremely low or high.

Distribution and bell-shaped curve . In normally distributed data, most points are grouped around the middle. Thus, most people have medium intelligence, and only a few are extremely low or high.

Operant conditioning . In many cases, the reflex does not arise because of the previous stimulus, but because of the consequences. If a mouse receives food whenever it presses a lever, it is more likely to press it. If you are sick every time you eat pineapple, you are unlikely to continue to eat them often.

Operant conditioning . In many cases, the reflex does not arise because of the previous stimulus, but because of the consequences. If a mouse receives food whenever it presses a lever, it is more likely to press it. If you are sick every time you eat pineapple, you are unlikely to continue to eat them often.

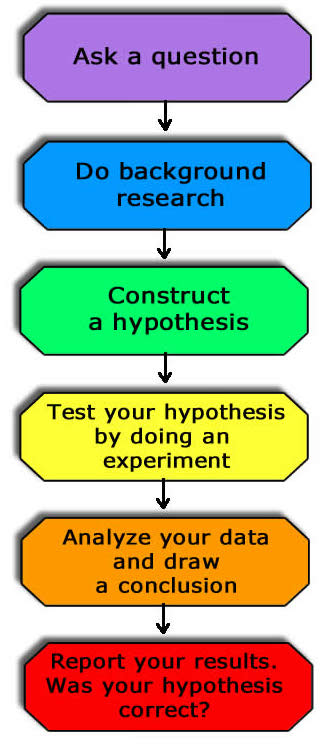

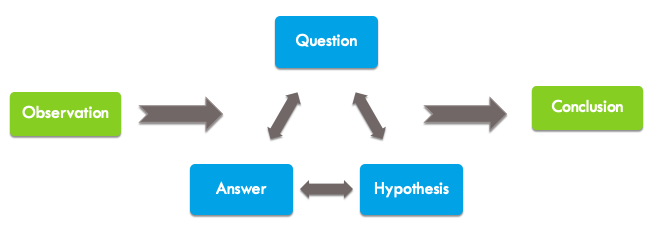

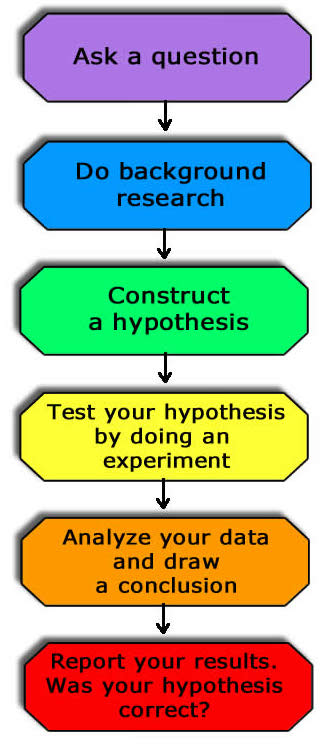

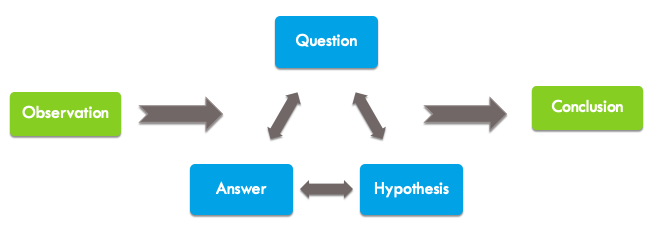

Scientific method. A scientific discovery usually follows a standard process: ask a question, form a hypothesis, conduct an experiment to test this hypothesis and report the results. We use this not only in our research, but also to test the research of others by assessing the correspondence between key questions, hypotheses, experimental procedures and conclusions.

Scientific method. A scientific discovery usually follows a standard process: ask a question, form a hypothesis, conduct an experiment to test this hypothesis and report the results. We use this not only in our research, but also to test the research of others by assessing the correspondence between key questions, hypotheses, experimental procedures and conclusions.

Each of these models simplifies something complicated in such a way that it can be useful for practitioners and teachers alike. This thinking is focused on the interpretation of problems and decision making. Models, on the other hand, are tools. The more tools you have, the better prepared you are for solving many problems.

Mental models are special tools for a particular profession. Over the past hundred years, medicine has gone through its cognitive revolution, creating advanced mental models. Even with 60,000 possible diagnoses and 4,000 procedures, doctors effectively use such simple models:

13 organ systems . There are many components in the body, but they can be considered as separate, mostly autonomous systems. Specialists usually focus on in-depth study of one of these systems. This makes learning more manageable.

13 organ systems . There are many components in the body, but they can be considered as separate, mostly autonomous systems. Specialists usually focus on in-depth study of one of these systems. This makes learning more manageable.

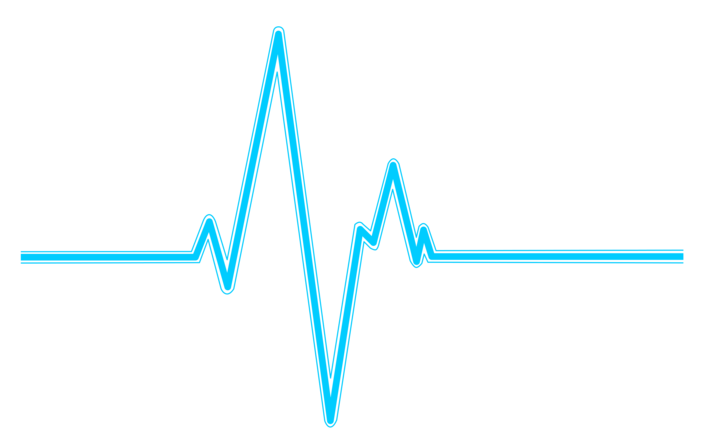

Four vital indicators. The entropy of the human body is enormous. There are four basic vital signs for detecting significant changes: temperature, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and heart rate. Medical workers of all levels are able to continuously collect this information as a permanent means of preliminary diagnostic assessment.

Four vital indicators. The entropy of the human body is enormous. There are four basic vital signs for detecting significant changes: temperature, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and heart rate. Medical workers of all levels are able to continuously collect this information as a permanent means of preliminary diagnostic assessment.

Ten point scale of pain . Pain is an important diagnostic measurement because it indicates the effectiveness of treatment or therapy. But pain is difficult to objectively measure. At the same time, a simple graphical pain scale helps doctors communicate effectively with patients and notice pain changes from a baseline.

Ten point scale of pain . Pain is an important diagnostic measurement because it indicates the effectiveness of treatment or therapy. But pain is difficult to objectively measure. At the same time, a simple graphical pain scale helps doctors communicate effectively with patients and notice pain changes from a baseline.

There are also mental models in the computer industry that we rely heavily on, although we usually don’t call them mental models. For instance,

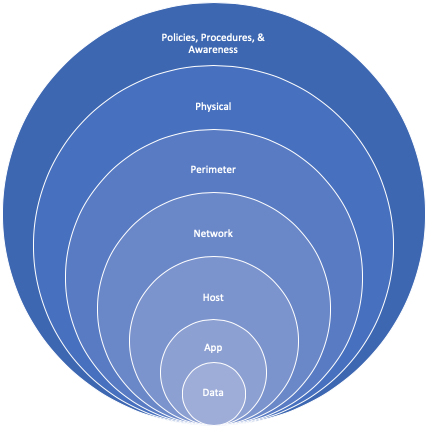

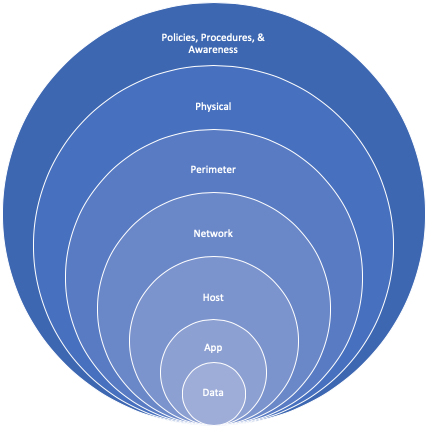

Defense in depth (defense in depth, DID). An approach to security architecture where additional categories (investigation, defense, response, etc.) are layered to provide an extensive comprehensive position.

Defense in depth (defense in depth, DID). An approach to security architecture where additional categories (investigation, defense, response, etc.) are layered to provide an extensive comprehensive position.

OSI model . Hierarchical classification of network communication functions used to develop and analyze communication protocols and their interaction. OS and application developers use the OSI model to develop functionality and set boundaries. Administrators and analysts use it to troubleshoot and investigate network problems and incidents.

OSI model . Hierarchical classification of network communication functions used to develop and analyze communication protocols and their interaction. OS and application developers use the OSI model to develop functionality and set boundaries. Administrators and analysts use it to troubleshoot and investigate network problems and incidents.

Investigation process. An investigation of security threats usually follows this process: detect suspicious input data, ask questions, form a hypothesis, start searching for answers - and repeat the procedure until it comes to a conclusion. Security analysts use this process to chronicle events and decide what evidence to analyze.

Investigation process. An investigation of security threats usually follows this process: detect suspicious input data, ask questions, form a hypothesis, start searching for answers - and repeat the procedure until it comes to a conclusion. Security analysts use this process to chronicle events and decide what evidence to analyze.

You constantly use all kinds of mental models, but they do not exist in a vacuum. Each of us perceives the world through the prism of our own unique perception, created under the influence of life experience. Although the prism is constantly changing, these models are not applied one after another. Instead, perception consists of layering many models .

Sometimes these are auxiliary extraneous models. For example, the Occam razor model assumes that the simplest explanation is usually correct. The doctor can use this principle together with mental models for deductive reasoning and assessment of mental state. For example, rapid weight loss may not be due to pancreatic cancer or hundreds of other diseases, but simply because the person does not eat enough, possibly due to depression. It sounds simple, but to draw such a conclusion requires tremendous thoughtfulness and awareness.

In other cases, we take into account competing mental models that contradict each other: for example, religion and state citizenship. Christianity dictates “do not kill”, but a democratic state offers citizens to go to war in order to preserve their freedoms. These conflicts give rise to internal strife, during which often compromises are required.

When confronted with a new suitable mental model, we include it in our personal set. Everything that we think about, each of our actions passes through the filter from these mental models, which push towards actions or contradict each other.

Information security practitioners are desperate for new models, further emphasizing the cognitive crisis. In fact, we often take good models and abuse them or expand them beyond their practical purpose.

The MITER ATT & CK attack knowledge base is a list of common methods for describing network attacks. This is a great model that is useful in many ways, and frankly, at some point, something like that was necessary.

But since the models are so lacking, some organizations began to abandon other security principles and successful initiatives, limiting themselves to checking on the MITER ATT & CK list. In the same way, I saw how new security organizations focus all their detection and prevention strategies only on the basis of ATT & CK without first formulating a threat model, without understanding valuable assets and assessing risks. This is the road to nowhere. This is not MITRE's fault: the developers of this framework themselves are actively trying to explain when to and when to not use ATT & CK, emphasizing the limitations of the framework.

The problem is that we lack models, so we immediately use and abuse any reasonable model as soon as it appears. Ultimately, good models are needed. A robust toolbox is required. But not everywhere you can use a hammer, and we do not need fourteen circular saws.

I already mentioned several models that help simplify education and practice in IT, but useful and generally accepted models are still not enough. What determines a good model?

A good model is simple . Models help deal with the complexity of problems. If they themselves are more complex than problems, then the benefits are diminished. The brevity of the wording is important. A 20-page description of the purpose and application of the model is useful, but simple graphics that convey the essence greatly simplify the perception and use. The model can be represented in the form of a diagram, table or even a simple list.

Good model is useful. The model should be wide enough to apply to well-known people and situations, but specific enough to use it for a practical understanding of specific scenarios. Imagine it as a highway junction exit. The exit is clearly visible, it is easy to drive to it at low speed. Once inside, the track should provide maximum acceleration so that you move at a convenient pace. Excellent models provide a person with a path from existing knowledge to complex concepts.

A good model is imperfect. Most models are generalizations created by inductive reasoning. There are always borderline situations, and these exceptions are important because they provide a mechanism for refuting the model. The key to understanding a theory or system is knowing when it does not work. Since the models are imperfect, they cannot be applied to any situation. The model should have clear criteria for use so that it is not used in inappropriate situations.

Most models are created by inductive reasoning . Inductive reasoning is the process of forming generalizations based on life experience, observations, or collected data. If you come across several malicious obfuscated PowerShell scripts, then you can generalize that obfuscation is a sign of a malicious script. This is not a model, but a heuristic (rule of thumb) that is potentially useful in research. It combines with several others and forms a model for research, evidence, or something else.

The strength of inductive reasoning depends on the number and variety of observations on which the conclusions are based.. I once worked with an analyst who saw a couple of times how attackers use the Nginx web server in their infrastructure. However, he never saw that Nginx was used for legitimate purposes, so he made the inductive conclusion that this web server is usually used by cybercriminals. Of course, Nginx is used by everyone, and this inductive heuristic is not based on the corresponding pattern, which led to poor conclusions and lost time.

When creating a model, the bar of evidence is even higher. The model should be based on a huge number of observations in a wide range of measurements.

I believe most models start with the right question. For example, is a hot dog a sandwich?

This is the wrong question. But it allows you to come to the right question. Regardless of your opinion, even a brief discussion ultimately leads you to the right question: “What is the definition of a sandwich?”

This is the wrong question. But it allows you to come to the right question. Regardless of your opinion, even a brief discussion ultimately leads you to the right question: “What is the definition of a sandwich?”

This is the right question. In the answer, you list the properties of the sandwich and the relationship between these properties.

A sandwich has several layers, the outer layer is usually based on carbohydrates, etc. ...

You clarify these properties by highlighting clear examples of sandwiches and non-sandwiches, taking into account the discussion of borderline situations.

Italian Hero is definitely a sandwich. Pizza - obviously not. What is the difference? How to apply this to a hot dog?

Discussions must be rich and varied in order to get a unique perspective. They reveal a host of borderline situations and cultural differences that you have not thought of.

How about tacos? This is a variant of a sandwich in a particular culture. How to apply it in the model?

Discussion creates value. The right questions and answers to them are a lot of work to come to a useful model.

By the way, a cube rule is one way to determine if a hot dog is a sandwich. Just don’t swear, it's just an option.

Mental models allow you to make better decisions and learn faster. These are tools that simplify complexity and are crucial in any profession. For information security to overcome the cognitive crisis, we must become more skilled in developing, using, and teaching good models. If you want to know more about specific information security models, some of them are listed below.

The situation is not unique to our profession. Similar problems were previously encountered by medicine, law, accounting and other areas. Using their example, one can identify several signs that determine the cognitive crisis:

Demand for specialists significantly exceeds supply. For experienced professionals, there are a huge number of vacancies. Since many organizations need experience, they are not able to invest properly in the training of their employees. The deficit greatly inflates the salaries of practitioners with relevant skills, and hyperspecialization occurs.

Most of the information is unreliable and unverifiable . There are few authoritative sources of knowledge about critical components and procedures. Practitioners rely heavily on personal experience and observations that are unverified and objectively unverified. This makes it difficult to reliably learn new information and makes it even more difficult to develop best practices and measure success.

Major industry problems persist that cannot be resolved systematically. The industry is not able to organize or effectively deal with the biggest problems that it faces. In medicine, these are epidemics and crises, in accounting, large-scale uncontrolled thefts through falsification of reporting. And the worms of the 2000s are still rampant on computer networks: there are hundreds of thousands of hosts with vulnerable SMB ports on the Internet, and there are no signs that the crypto ransomware epidemic is on the decline. Many of the main problems that we faced twenty years ago have survived or become even worse.

As other areas emerged from the cognitive crisis more formalized and effective, information security has hope. We can learn from them and make our own cognitive revolution . Three things must happen:

As other areas emerged from the cognitive crisis more formalized and effective, information security has hope. We can learn from them and make our own cognitive revolution . Three things must happen:- We must thoroughly understand the processes on the basis of which conclusions are drawn.

- Experts should develop reliable, repeatable teaching methods and techniques.

- Teachers should build and promote practical thinking.

At the center of all three pillars of the cognitive revolution is the concept of the mental model.

Mental models

The mental model is just a way of looking at the world. We are surrounded by complex systems, so the brain creates models to simplify.

You use mental models all the time. Here are a few examples:

Distribution and bell-shaped curve . In normally distributed data, most points are grouped around the middle. Thus, most people have medium intelligence, and only a few are extremely low or high.

Distribution and bell-shaped curve . In normally distributed data, most points are grouped around the middle. Thus, most people have medium intelligence, and only a few are extremely low or high.  Operant conditioning . In many cases, the reflex does not arise because of the previous stimulus, but because of the consequences. If a mouse receives food whenever it presses a lever, it is more likely to press it. If you are sick every time you eat pineapple, you are unlikely to continue to eat them often.

Operant conditioning . In many cases, the reflex does not arise because of the previous stimulus, but because of the consequences. If a mouse receives food whenever it presses a lever, it is more likely to press it. If you are sick every time you eat pineapple, you are unlikely to continue to eat them often.  Scientific method. A scientific discovery usually follows a standard process: ask a question, form a hypothesis, conduct an experiment to test this hypothesis and report the results. We use this not only in our research, but also to test the research of others by assessing the correspondence between key questions, hypotheses, experimental procedures and conclusions.

Scientific method. A scientific discovery usually follows a standard process: ask a question, form a hypothesis, conduct an experiment to test this hypothesis and report the results. We use this not only in our research, but also to test the research of others by assessing the correspondence between key questions, hypotheses, experimental procedures and conclusions. Each of these models simplifies something complicated in such a way that it can be useful for practitioners and teachers alike. This thinking is focused on the interpretation of problems and decision making. Models, on the other hand, are tools. The more tools you have, the better prepared you are for solving many problems.

Applied models

Mental models are special tools for a particular profession. Over the past hundred years, medicine has gone through its cognitive revolution, creating advanced mental models. Even with 60,000 possible diagnoses and 4,000 procedures, doctors effectively use such simple models:

13 organ systems . There are many components in the body, but they can be considered as separate, mostly autonomous systems. Specialists usually focus on in-depth study of one of these systems. This makes learning more manageable.

13 organ systems . There are many components in the body, but they can be considered as separate, mostly autonomous systems. Specialists usually focus on in-depth study of one of these systems. This makes learning more manageable.  Four vital indicators. The entropy of the human body is enormous. There are four basic vital signs for detecting significant changes: temperature, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and heart rate. Medical workers of all levels are able to continuously collect this information as a permanent means of preliminary diagnostic assessment.

Four vital indicators. The entropy of the human body is enormous. There are four basic vital signs for detecting significant changes: temperature, respiratory rate, blood pressure, and heart rate. Medical workers of all levels are able to continuously collect this information as a permanent means of preliminary diagnostic assessment.  Ten point scale of pain . Pain is an important diagnostic measurement because it indicates the effectiveness of treatment or therapy. But pain is difficult to objectively measure. At the same time, a simple graphical pain scale helps doctors communicate effectively with patients and notice pain changes from a baseline.

Ten point scale of pain . Pain is an important diagnostic measurement because it indicates the effectiveness of treatment or therapy. But pain is difficult to objectively measure. At the same time, a simple graphical pain scale helps doctors communicate effectively with patients and notice pain changes from a baseline. There are also mental models in the computer industry that we rely heavily on, although we usually don’t call them mental models. For instance,

Defense in depth (defense in depth, DID). An approach to security architecture where additional categories (investigation, defense, response, etc.) are layered to provide an extensive comprehensive position.

Defense in depth (defense in depth, DID). An approach to security architecture where additional categories (investigation, defense, response, etc.) are layered to provide an extensive comprehensive position.  OSI model . Hierarchical classification of network communication functions used to develop and analyze communication protocols and their interaction. OS and application developers use the OSI model to develop functionality and set boundaries. Administrators and analysts use it to troubleshoot and investigate network problems and incidents.

OSI model . Hierarchical classification of network communication functions used to develop and analyze communication protocols and their interaction. OS and application developers use the OSI model to develop functionality and set boundaries. Administrators and analysts use it to troubleshoot and investigate network problems and incidents.  Investigation process. An investigation of security threats usually follows this process: detect suspicious input data, ask questions, form a hypothesis, start searching for answers - and repeat the procedure until it comes to a conclusion. Security analysts use this process to chronicle events and decide what evidence to analyze.

Investigation process. An investigation of security threats usually follows this process: detect suspicious input data, ask questions, form a hypothesis, start searching for answers - and repeat the procedure until it comes to a conclusion. Security analysts use this process to chronicle events and decide what evidence to analyze. You constantly use all kinds of mental models, but they do not exist in a vacuum. Each of us perceives the world through the prism of our own unique perception, created under the influence of life experience. Although the prism is constantly changing, these models are not applied one after another. Instead, perception consists of layering many models .

Sometimes these are auxiliary extraneous models. For example, the Occam razor model assumes that the simplest explanation is usually correct. The doctor can use this principle together with mental models for deductive reasoning and assessment of mental state. For example, rapid weight loss may not be due to pancreatic cancer or hundreds of other diseases, but simply because the person does not eat enough, possibly due to depression. It sounds simple, but to draw such a conclusion requires tremendous thoughtfulness and awareness.

In other cases, we take into account competing mental models that contradict each other: for example, religion and state citizenship. Christianity dictates “do not kill”, but a democratic state offers citizens to go to war in order to preserve their freedoms. These conflicts give rise to internal strife, during which often compromises are required.

When confronted with a new suitable mental model, we include it in our personal set. Everything that we think about, each of our actions passes through the filter from these mental models, which push towards actions or contradict each other.

Models from Despair

Information security practitioners are desperate for new models, further emphasizing the cognitive crisis. In fact, we often take good models and abuse them or expand them beyond their practical purpose.

The MITER ATT & CK attack knowledge base is a list of common methods for describing network attacks. This is a great model that is useful in many ways, and frankly, at some point, something like that was necessary.

But since the models are so lacking, some organizations began to abandon other security principles and successful initiatives, limiting themselves to checking on the MITER ATT & CK list. In the same way, I saw how new security organizations focus all their detection and prevention strategies only on the basis of ATT & CK without first formulating a threat model, without understanding valuable assets and assessing risks. This is the road to nowhere. This is not MITRE's fault: the developers of this framework themselves are actively trying to explain when to and when to not use ATT & CK, emphasizing the limitations of the framework.

The problem is that we lack models, so we immediately use and abuse any reasonable model as soon as it appears. Ultimately, good models are needed. A robust toolbox is required. But not everywhere you can use a hammer, and we do not need fourteen circular saws.

What defines a good model?

I already mentioned several models that help simplify education and practice in IT, but useful and generally accepted models are still not enough. What determines a good model?

A good model is simple . Models help deal with the complexity of problems. If they themselves are more complex than problems, then the benefits are diminished. The brevity of the wording is important. A 20-page description of the purpose and application of the model is useful, but simple graphics that convey the essence greatly simplify the perception and use. The model can be represented in the form of a diagram, table or even a simple list.

Good model is useful. The model should be wide enough to apply to well-known people and situations, but specific enough to use it for a practical understanding of specific scenarios. Imagine it as a highway junction exit. The exit is clearly visible, it is easy to drive to it at low speed. Once inside, the track should provide maximum acceleration so that you move at a convenient pace. Excellent models provide a person with a path from existing knowledge to complex concepts.

A good model is imperfect. Most models are generalizations created by inductive reasoning. There are always borderline situations, and these exceptions are important because they provide a mechanism for refuting the model. The key to understanding a theory or system is knowing when it does not work. Since the models are imperfect, they cannot be applied to any situation. The model should have clear criteria for use so that it is not used in inappropriate situations.

Model creation

Most models are created by inductive reasoning . Inductive reasoning is the process of forming generalizations based on life experience, observations, or collected data. If you come across several malicious obfuscated PowerShell scripts, then you can generalize that obfuscation is a sign of a malicious script. This is not a model, but a heuristic (rule of thumb) that is potentially useful in research. It combines with several others and forms a model for research, evidence, or something else.

The strength of inductive reasoning depends on the number and variety of observations on which the conclusions are based.. I once worked with an analyst who saw a couple of times how attackers use the Nginx web server in their infrastructure. However, he never saw that Nginx was used for legitimate purposes, so he made the inductive conclusion that this web server is usually used by cybercriminals. Of course, Nginx is used by everyone, and this inductive heuristic is not based on the corresponding pattern, which led to poor conclusions and lost time.

When creating a model, the bar of evidence is even higher. The model should be based on a huge number of observations in a wide range of measurements.

I believe most models start with the right question. For example, is a hot dog a sandwich?

This is the wrong question. But it allows you to come to the right question. Regardless of your opinion, even a brief discussion ultimately leads you to the right question: “What is the definition of a sandwich?”

This is the wrong question. But it allows you to come to the right question. Regardless of your opinion, even a brief discussion ultimately leads you to the right question: “What is the definition of a sandwich?” This is the right question. In the answer, you list the properties of the sandwich and the relationship between these properties.

A sandwich has several layers, the outer layer is usually based on carbohydrates, etc. ...

You clarify these properties by highlighting clear examples of sandwiches and non-sandwiches, taking into account the discussion of borderline situations.

Italian Hero is definitely a sandwich. Pizza - obviously not. What is the difference? How to apply this to a hot dog?

Discussions must be rich and varied in order to get a unique perspective. They reveal a host of borderline situations and cultural differences that you have not thought of.

How about tacos? This is a variant of a sandwich in a particular culture. How to apply it in the model?

Discussion creates value. The right questions and answers to them are a lot of work to come to a useful model.

By the way, a cube rule is one way to determine if a hot dog is a sandwich. Just don’t swear, it's just an option.

Conclusion

Mental models allow you to make better decisions and learn faster. These are tools that simplify complexity and are crucial in any profession. For information security to overcome the cognitive crisis, we must become more skilled in developing, using, and teaching good models. If you want to know more about specific information security models, some of them are listed below.

References

- Simon, H. A. (1957). “Human models; social and rational. ”

- Page, S. (2018). “Thinking in Models: What You Need to Know for Information to Work for You,” Basic Books, NY

- Bell-shaped curve

- Operant conditioning

- Scientific method

- OSI Model

- Organ systems

- Vital signs

- Ten point pain scale

Different models of information security

- Investigation process

- Diamond invasion analysis

- MITER ATT & CK

- Defense in depth (Defense in Depth)

- Pyramid pain (Pyramid of Pain)

- Chain kiberubiystva (Cyber Kill Chain)

- The intention of the evidence (Evidence Intention)

- PICERL Incident Response Process