How Edison invented wireless and understood nothing

We are so used to associating wireless with radio waves that it seems impossible for us to invent a wireless telegraph before the famous Hertz experiments of 1887. Wireless electromagnetic communication as if automatically implies radio and brings us back to the eternal debate about the priority of Marconi-Lodge-Popov.

However, since 1831, physicists have known the law of electromagnetic induction. Although it is a necessary condition for the existence of radio waves, it can also be used independently, even if nothing is known about the waves. In particular, it can be used to create a wireless telegraph. One of the pioneers of this type of communication, long before Marconi, was Edison, proving himself to be a brilliant practitioner - and, alas, a completely hopeless theorist.

Scientific American

Scientific American

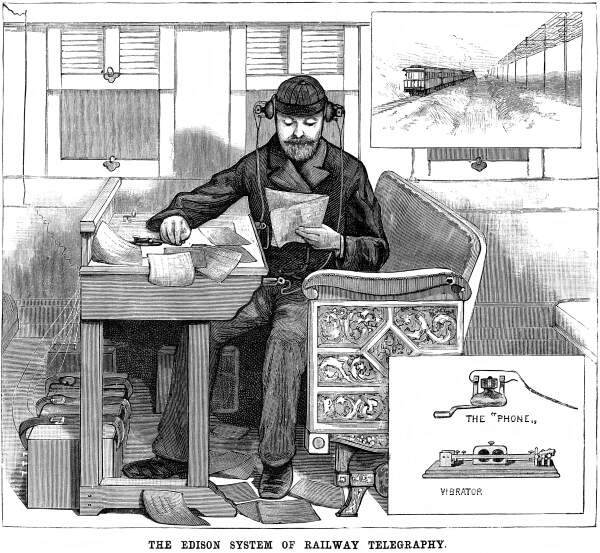

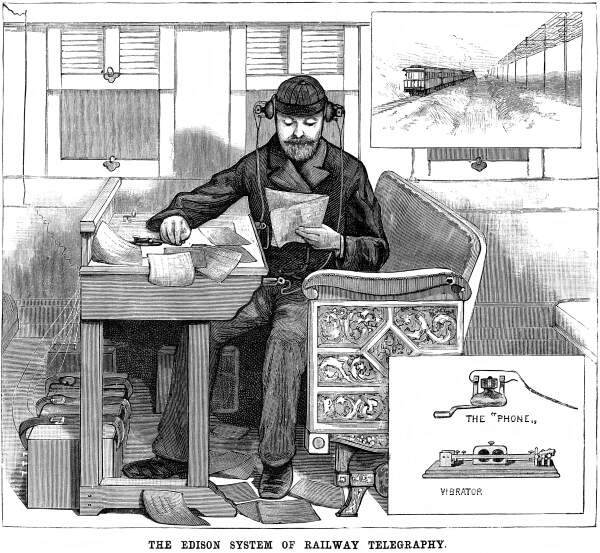

In 1886, Scientific American magazine published an amazing article , The Edison Rail Telegraph System , which describes not just a demo installation, but a fully functional wireless telegraph. It is still difficult to call it completely wireless, because he used ordinary telegraph wires stretched along the railway. But the transmission of messages from a moving train to these wires and back occurred exclusively due to the electromagnetic field.

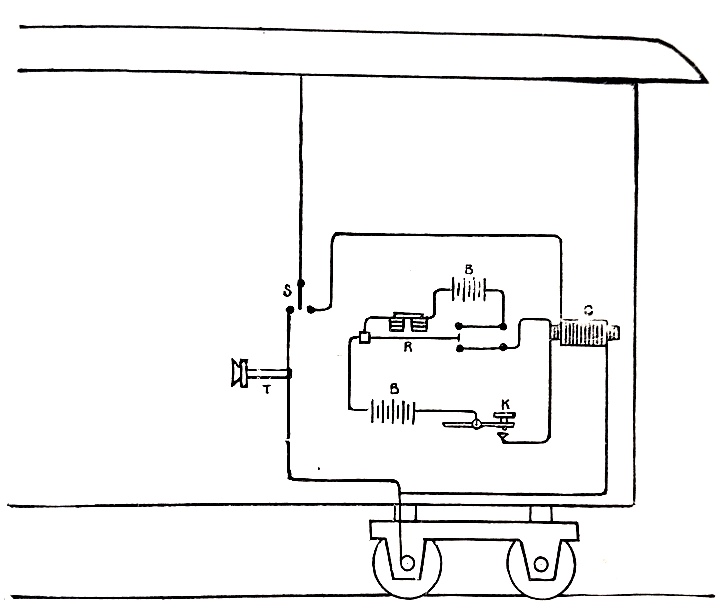

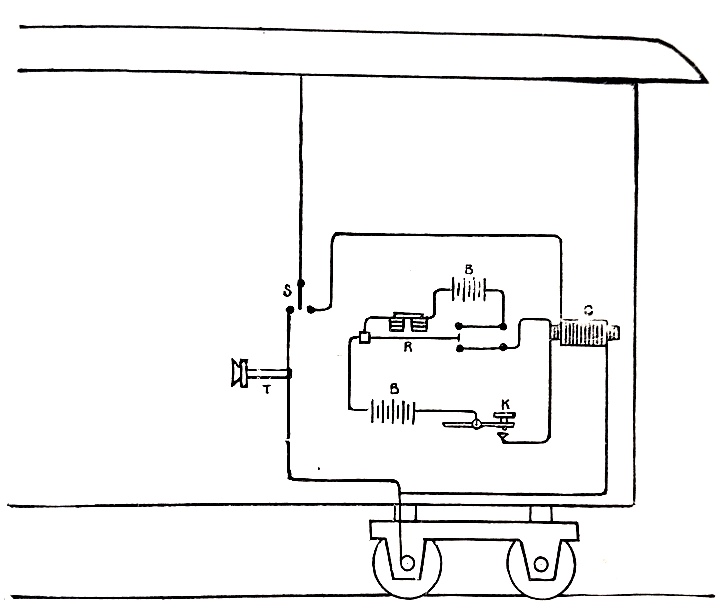

As an antenna, sheets of tin were used, which covered the roofs of four cars. In the reception mode, the wire from the antenna was directly connected by the S key through the T speaker to the ground, for which a copper plate served, pressed by the spring to the wheel axis of the car. In transmission mode, key S closed another circuit, consisting of battery B, telegraph key K, reed switch R and transformer C. The reed switch worked on the basis of an electric bell and, when the telegraph key was closed, converted the DC voltage from the battery to alternating voltage with a frequency of 500 Hz . This voltage was then increased by a transformer and supplied to the antenna.

Scientific american

It can be calculated that the length of the electromagnetic wave at a frequency of 500 Hz would be 600 km. At the same time, the distance of wireless transmission in railway experiments was 5-6 m. The journal also reported on other Edison experiments, where the distance reached 175 m. However, all these ranges are much shorter than the wavelength, and therefore, wave phenomena proper (mutual generation of electric and magnetic fields) and explain the operation of the telegraph by the law of induction alone. Apparently, this circumstance does not allow Edison to be ranked among the inventors of the radio.

Be that as it may, the magazine proudly concluded that Edison’s telegraph, at a modest cost, offers tremendous opportunities to prevent railroad accidents and capture criminals. It is known that in 1888 this telegraph was used to maintain communication with trains stuck in snowdrifts during a snowstorm.

However, the most incomprehensible is the theoretical explanation that Edison gave his invention at the request of the correspondent. It should be quoted verbatim:

It turns out that not even the "world ether", but the most ordinary air forced Edison to apply alternating current. It is curious to imagine how Edison imagined the work of his telegraph in a vacuum. Should communication cease altogether? Or vice versa, to work flawlessly even with direct current, without encountering any resistance of an insidious dielectric in its path? But it seems that Edison was too convinced a pragmatist to be distracted by idle questions about the telegraph in a vacuum.

However, since 1831, physicists have known the law of electromagnetic induction. Although it is a necessary condition for the existence of radio waves, it can also be used independently, even if nothing is known about the waves. In particular, it can be used to create a wireless telegraph. One of the pioneers of this type of communication, long before Marconi, was Edison, proving himself to be a brilliant practitioner - and, alas, a completely hopeless theorist.

In 1886, Scientific American magazine published an amazing article , The Edison Rail Telegraph System , which describes not just a demo installation, but a fully functional wireless telegraph. It is still difficult to call it completely wireless, because he used ordinary telegraph wires stretched along the railway. But the transmission of messages from a moving train to these wires and back occurred exclusively due to the electromagnetic field.

As an antenna, sheets of tin were used, which covered the roofs of four cars. In the reception mode, the wire from the antenna was directly connected by the S key through the T speaker to the ground, for which a copper plate served, pressed by the spring to the wheel axis of the car. In transmission mode, key S closed another circuit, consisting of battery B, telegraph key K, reed switch R and transformer C. The reed switch worked on the basis of an electric bell and, when the telegraph key was closed, converted the DC voltage from the battery to alternating voltage with a frequency of 500 Hz . This voltage was then increased by a transformer and supplied to the antenna.

Scientific american

It can be calculated that the length of the electromagnetic wave at a frequency of 500 Hz would be 600 km. At the same time, the distance of wireless transmission in railway experiments was 5-6 m. The journal also reported on other Edison experiments, where the distance reached 175 m. However, all these ranges are much shorter than the wavelength, and therefore, wave phenomena proper (mutual generation of electric and magnetic fields) and explain the operation of the telegraph by the law of induction alone. Apparently, this circumstance does not allow Edison to be ranked among the inventors of the radio.

Be that as it may, the magazine proudly concluded that Edison’s telegraph, at a modest cost, offers tremendous opportunities to prevent railroad accidents and capture criminals. It is known that in 1888 this telegraph was used to maintain communication with trains stuck in snowdrifts during a snowstorm.

However, the most incomprehensible is the theoretical explanation that Edison gave his invention at the request of the correspondent. It should be quoted verbatim:

Mr. Edison believes that he made a new discovery in physics. He finds that bodies that were still considered non-conductive, such as air, actually become such only after some time has passed. In the first instant of discharge, air does not create any resistance to the passage of current, but almost immediately becomes polarized, and communication is interrupted. Therefore, the idea contained in these very short high-voltage waves is to allow them to reach the wires before the air has any resistance. However, the period between them is made sufficient to allow air to return to its normal state and, therefore, to allow subsequent waves to pass.Edison cannot be denied some talent for “simple” explanations. In his discussion of the non-instantaneous nature of the polarization of dielectrics, one can see a reasonable grain. However, the explanation as a whole does not hold water. Apparently, the passage of the signal through the air seemed to Edison to be a discharge in the literal sense of the word, a kind of lightning, but extremely short. The correspondent timidly adds that the word "discharge" probably should be understood conditionally, since we are talking about induction, and not about charge flow. However, this idea does not find any development in the article and is not confirmed by the words of Edison himself.

It turns out that not even the "world ether", but the most ordinary air forced Edison to apply alternating current. It is curious to imagine how Edison imagined the work of his telegraph in a vacuum. Should communication cease altogether? Or vice versa, to work flawlessly even with direct current, without encountering any resistance of an insidious dielectric in its path? But it seems that Edison was too convinced a pragmatist to be distracted by idle questions about the telegraph in a vacuum.