Demis Hassabis - the great intellect that created the great intellect

- Transfer

“We need an exponential improvement in human behavior or an exponential improvement in technology, and the world does not look as if it is acting on the first principle.”

For the CEO of the half-billion company Demis Hassabis, the working day starts very ordinary. No cabbage cocktail at 5 in the morning reading The Wall Street Journal, no intense training followed by breakfast. Instead, he arrives at a reasonable time in his office, located next to Kings Cross in London, spends the day at meetings, and then returns home to a family dinner with his wife and two children at 7:30 pm

There he can relax and put the children to bed at 10 pm, starting what he calls the “second working day”. And then things get a little less trivial.

“I do not sleep until 4 am,” he says. "Sometimes until 4.30, depending on how things are going."

If the first half of his working day is devoted to running a business and managing 700 employees - 400 of whom are doctors of science, trying to maintain their position as a leading global company in the field of artificial intelligence, then in the second half of the working day he reminds himself why he basically controls this company . It is about computer science, mathematics, and how to keep up with the times. "That's when I do my research work."

Translation - Diana Sheremyeva.

The translation was made with the support of the company EDISON Software , which professionally deals with security , as well as develops electronic medical verification systems .

Although he guiltily admits that in the last couple of weeks this “study” is largely associated with the analysis of chess matches. Hassabis' company, DeepMind, bought by Google in 2014 for £ 400 million, is the British equivalent of the company Ilona Mask, at least in terms of ambition. It is aimed not at increasing, but at transformation. His task: "To understand artificial intelligence, and then use it to solve the rest."

During our meeting, the 42-year-old Hassabis is very thoughtful. A few days after our interview, DeepMind will do something strange for a supposedly profitable enterprise. They will publish a scientific article describing a key part of their intellectual property — and an important step in achieving this incredible goal.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that this article left behind the last word in the most amazing story of all the time of the existence of artificial intelligence. This is a program developed by his company called AlphaGo, which was then converted to another program called AlphaZero. This program is not only a solution to one of the biggest challenges in the field of AI - to defeat a person in the strategic board game Go - it uses such a general approach that, after some rethinking, it can potentially also become the best chess program in the world.

It is possible to argue (which is what philosophers do) whether this program really "possesses intelligence". But for Hassabis, she was the climax of the journey that led him to Cambridge and University College London; that journey, thanks to which he became a chess grandmaster at the age of 13 and a software developer, selling for millions of dollars even when Hassabis himself was a teenager. And this journey began in Finchley, in the north of London, when the very young Hassabis began to think about the secrets of the human mind.

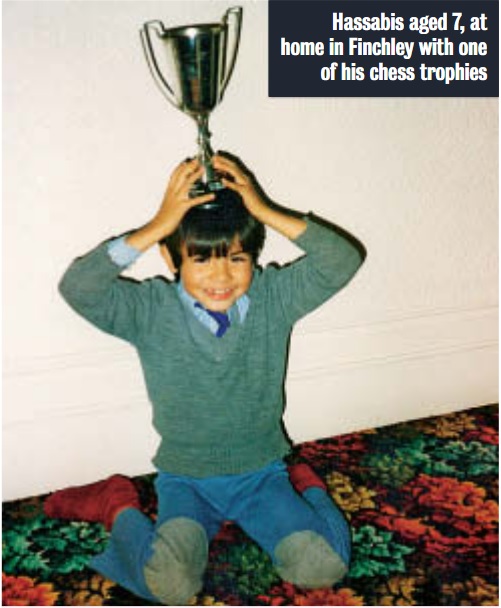

Hassabis at the age of 7 at his home in Finchley, with one of his trophies for winning the chess game.

However, Demis Hassabis spent his “second working day” until late analyzing chess matches not because of AlphaZero. He did this because some of his old friends are in the city. During our meeting with him in London, the final of the World Chess Championship is held, in which, after 12 intense games, the current Norwegian champion Magnus Carlsen eventually won.

This meant that being in the middle of a traveling circus of coaches, commentators and various grandmasters, Hassabis experienced his youth. “It was a chess festival,” he says.

“I was joking with Judith Polgar [a famous grandmaster] just now, in fact. I have not seen her for 30 years. ” He and Polgar are almost the same age, and when they were 12 they were fierce competitors. “She was No. 1 when I was No. 2.” When he says “No. 2,” he means in the world — Polgar from Hungary. They were the best in their age group.

Alas, it was the peak of his chess career. Suddenly, for all he threw chess. He never reached the level of a grandmaster and watched as Polgar became the best female player in history. Chess, he decided, was not for him. “I like what these people do. There is some professional integrity in devoting your brain and your consciousness to this, ”he says. "I knew from the very beginning that I was much better as a station wagon."

For a former child prodigy, a person with a terribly frightening intelligence and superhuman work schedule, Hassabis does not even bother to be socially inferior. Although his short stature and glasses make him live make him look a little like suave Pinfold from the Dangerous Mouse series, he doesn’t have strange ticks, he doesn’t hide his eyes on the floor when talking to you. It is not only normal for a programmer, but, unfortunately, it seems quite normal for an ordinary person.

In a sense, that's why he threw chess. “There are too many fascinating things in the world to spend your whole life on obsession,” he says. “That's how I felt when I was young. I loved physics, art, a lot of things. To become Magnus Carlsen, you must be seriously obsessed. I'm crazy, but all at once - if it's not an oxymoron. ”

At first, because of his life journey, Hassabis seems to be one of the most eminent lovers. He moves from discipline to discipline, from business to university, from university to business, without stopping at all - at least not until now. But perhaps the most surprising thing is (and you will soon see that this is not an indulgent assertion) that this was planned.

The most logical thing to begin the story of his career with - I'm not kidding - the times when Demis was 4 years old. It was then that he first became interested in a chessboard. “For me, it all started with chess. Chess is an improvement in decision making. Until I was 12 or 13, I considered myself a professional chess player. Although it was a child. You study hard, talk with coaches, analyze your own games, think about how you can improve your skills.

“It made me think about the process of thinking: what is intelligence, how does my brain come up with these ideas?” That's how he abandoned his chess career.Or, at least, he threw professional chess. David Silver, a fellow programmer and computer scientist, first met him several years later, when they were both 15 years old. “I participated in a junior chess competition in Suffolk,” says Silver. “Demis was a child returning from London and in need of pocket money. He will win the local tournament, take a £ 50 prize pool - that’s how he will earn his pocket money that weekend. ” Today, Silver works as a programmer at DeepMind, where he manages the AlphaZero project.

Most of this prize money went to what quickly became the new hobby of Hassabis. “I bought my first computer when I was 8 years old, with the money I received from winning a chess tournament,” he said. “My parents did not understand anything in computers, still do not understand. But they said nothing, it was my money. I started programming. I realized that a computer is an amazing, almost magical device to empower your mind. ”

You probably think what role his parents played in all this? What was his home education? Who made him learn? And when did he have the inevitable teenage breakdown?

At the age of 16 he worked on the initial version of artificial intelligence. “I knew it would be the greatest adventure in which to participate.But the truth is that his parents were not involved at all. His father, a Greek Cypriot, was a toy seller, and his mother was a Singaporean Chinese woman who worked for John Lewis. He describes them as “pretty bohemian” people and says that they always encouraged him and his brother and sister to pursue their interests. For his brother and sister, this meant music and literary work; for him, it meant something that they simply did not understand. "My parents lost the idea of what the hell I was doing when I was 14 or 15 years old."

It was the same when he moved away from them. There was a break between early final exams and university admission. He was accepted at Cambridge, but they said they would not allow him to study with them until he was older. Therefore, he took part in the programming competition with the game company Bullfrog and took second place.

Hassabis at 23 runs his second game development company, 1999

"They invited me to summer work." At that moment, they learned - like Cambridge - that he was a minor. "They said:" You can not work here. Hiring you illegally. " I asked: “Can I work anyway? "I was paid 200 pounds a week in brown paper envelopes. I paid for a room at the YMCA (* from the Young Men's Christian Association) - a youth volunteer organization. ) cash.

Here he earned much more than he could earn on summer work. He participated in the development of Theme Park, one of the most successful games of the nineties, with a circulation of 15 million copies. In particular, he was working on an elementary AI, which meant that artificial intelligence reacted to the way people played this game. Demis was 16 years old, and he began to see his future. “When I saw how successful this project was, I realized that it would be the greatest adventure in which to participate.” Since then, “It has been a fairly coordinated plan; I always had a company like DeepMind on my mind. ”

As a chess player, thinking 15 steps ahead, he wanted to arrange the pieces, performing various career and academic gambits, until he was able to strike.

The first figure he placed was Cambridge University, where a bachelor's degree in computer engineering supplemented his practical programming skills with more theoretical ones. “It was closer to mathematics than to computer science. I loved it all. That gave me a good base. ” Although he did not agree with their approach to artificial intelligence. “Everything revolved around logic. It was obvious to me that this was a road to nowhere. You can never program enough knowledge so that they suddenly become intelligent. We do not know enough about the knowledge in our own brains to present them as a set of certain rules. ”

The second step after Cambridge is a return to the creation of computer games, this time under his leadership. The goal, however, was not programming, but business. “I needed to learn how to manage the company and the teams.

After the release of two games - fans can remember Black & White and Republic: Revolution - he learned everything he wanted and closed his gaming studio. But: “There was still no time to create DeepMind. I needed a source of ideas besides computer science. Then I defended my doctoral dissertation in cognitive neuroscience. In particular, in the fields of neurobiology, we had little idea how to adapt to artificial intelligence. He wanted to know how the brain works in order to reproduce it on a computer.

Finally, in 2010, the time has come.

DeepMind, which Hassabis founded together with friends Mustafa Suleiman and Shane Legg, still works as a separate company. Since Google bought it - Europe's largest acquisition - DeepMind is based in the British headquarters in Kings Cross.

The office is the ultimate dream, there is everything that you could hope to see in the technology giant. This is a place where you rarely stay farther than a few steps from the ping-pong table, and if it does happen, then most likely it is because you are near a smoothie. At the reception desk, studiously dressed piercing administrators shake the air, telling them that this is just a temporary job that they need before their dance career develops. The windows are decorated in retro style, pixel characters of video games.

The only thing that slightly brings this mega stylish look is the employees themselves who walk past you with tucked t-shirts, always carrying laptops, exuding this smell, unmistakably recognizable, familiar from childhood if you spent your childhood in the Games Workshop. It’s as if a computer science course at the University of Cambridge suddenly moved to a trendy hipster coffeehouse in Dalston. Which, of course, is not too far from the truth.

But you can remove all glass, steel, and wooden walls, and you still have something else left. There are as many Go boards as there are ping-pong tables, and the boards filled with equations in the halls get more attention than the table football in front of them. When I am satisfied with the tour, I go through the Turing office, the von Neumann office and the Ramanujan conference room. “It was a big progress for women,” says one of the employees when we pass by two cabinets: Mary Schelli and Somerville.

Everywhere a huge, almost palpable sense of intellectual excitement. The sensation of boiling, as if there could be anything behind the doors. For some reason, it is not surprising that once in the Gauss room you find that the grandmaster and the international master are watching the tie-break matches of the World Chess Championship using AlphaZero analysis. “He just plays exquisite games,” says Matthew Sadler, the aforementioned grandmaster, since AlphaZero recommends a move missed by Magnus Carlsen.

Then I close this door and wonder what is next.

To understand why AlphaZero games are so special, why Sadler is so excited, you need to go back 21 years ago. In 1997, the computer Deep Blue bypassed Garry Kasparov, the world chess champion, in one of the most famous games ever played. This event was announced as the final battle of the man against the car.

However, in reality there was another game that computers could not overcome: Go, a board game in the Far East, in which there are much more game positions than atoms in the universe.

Go is a game that does not respond to a rough calculation. It requires intuition and an instinctive assessment of positions and beauty. Unlike chess, where by 2016 a mobile phone could play a trustworthy game even with a grandmaster, there were no programs that were close in level to the game Go. At that moment, many thought that in Go another 20 years would be human superiority. Hassabis thought otherwise.

Google bought DeepMind because it wanted to improve artificial intelligence in general, to develop programs that can be good not only in one thing - for example, in chess, but in many areas. In the end, this general intelligence can be used to solve scientific and commercial problems.

DeepMind, in fact, has already done some of these things - its software is used to recommend purchases on Google Play and it has reduced the energy consumption in Google’s server rooms. Two weeks ago, DeepMind won the competition to predict how proteins will fold — an esoteric skill that is actually crucial to all processes in the body. But a good way to prove to the whole world that artificial intelligence works is to do it in the same way as people, including Hassabis, usually do, to prove that there is intelligence through the game.

DeepMind's approach to Go was very different from the programs that were used previously. While Deep Blue needed a team of programmers and grandmasters to teach him chess tricks and pass on human knowledge accumulated over thousands of years, AlphaZero literally did not need anything. This program began life as a newborn born in the world of Go. All he knew was what he wanted to win, and all he had was a board and knowledge of the rules.

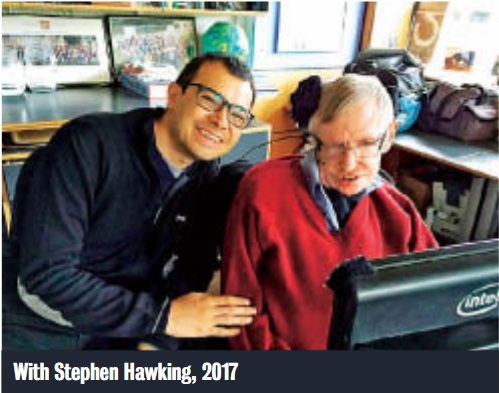

With Stephen Hawking, 2017

Then, as a child taking his first steps, for tens of thousands of games played against himself, he experimented and improved his understanding. Because of the lack of words, he learned intuition. Gradually, he independently mastered the skills of human masters, and also gained several of his own. He then used these skills to destroy the support of human intelligence. AlphaZero infancy was measured in hours, after which he was able to beat the best man in the world.

However, this was not enough. After Hassabis’s program became the undisputed computer champion of Go, he went to the conference to talk about his accomplishments. Murray Campbell, who was in the team of Deep Blue, who won Kasparov, approached him. "Murray asked:" What would he do if we tried it on chess? ". For an ordinary program, the question would be meaningless - Deep Blue knew how to play grandmaster chess, but asking them to play Go would be as ridiculous as asking them to play a pigeon. This would require starting all over again and developing a new system from scratch. For AlphaZero, this simply meant a new stage of infancy.

Thus, AlphaZero, was reborn in the world of black and white. This time, on the board were not Go flat chips, but queens, kings, elephants and queens of chess. “AlphaZero can start playing in the morning in a completely random way, then for tea he will have an inhuman level,” said Hassabis. “By lunchtime, it will be the strongest organization that has ever existed.” When he looked through the games, he realized that he was not just the best player in the world; it was not just the best computer; he also discovered a new way of playing.

“It's like chess from another planet,” said Hassabis. “You can appreciate this beauty. AlphaZero sacrifices figures, opening up new lines of attack. ” One grandmaster allowed to analyze his games, comparing this act with the search for old notebooks of the long-forgotten chess genius from the past.

In perspective, artificial intelligence will be able to think like a scientist and create discoveries of the Nobel Prize level.Because of table football and high ambitions, all this can justifiably sound like DeepMind is a parody of Silicon Valley. Only here if this is the case, then they will be in Silicon Valley for the time being. Hassabis is a programmer. In this programming of Valhalla, he achieved something that eluded Facebook, Microsoft, and all those before him: he kept collisions with the boredom of analog reality to a minimum.

Commission payments to monopolies or Senate hearings about Russia's interference in the elections are not for him. When DeepMind was bought by Google, they didn’t just make money; they got freedom.

“An important decision was made as to whether we should sell or not. Many compromises were required in both cases, ”he says. In the event of a sale, he lost one kind of autonomy — he suddenly had a boss. However, this is not the only autonomy. “One thing did not give me rest. It never seemed to me attractive to be a publicly quoted CEO. Then your life is just income and quarterly goals, not purely basic research. I prefer science.

Google was confident that this purchase is not like buying YouTube. They did not expect DeepMind to quickly make a profit. They are needed to solve the problem of intelligence; This is the Manhattan Computing Project. “I realized that if I did this with Google, I could be behind the scenes and continue to do science,” says Hassabis.

There is still much to do. Intellect is not solved simply by winning several board games. Chess is an extremely difficult problem, but also very simple. Unlike life, it has clear rules, clear results, and everyone knows what is happening. There are similar situations in real life - where, like in chess or Go, the solution is to choose the right path from a variety of possible combinations. One of the achievements they have already achieved is an understanding of protein folding, which is essential for the development of new drugs. Our inability to model the chemistry of protein in the body is one of the reasons why the development of new drugs is so expensive.

One of the strangest things in artificial intelligence programs is that people create them, but do not understand them. As soon as they begin to work, learn and develop, their work may become as incomprehensible to outsiders as our own brain.

For Hassabis, a chess program is a way to see the brain of AlphaZero. On the chessboard, unlike proteins, you can see a striking move. “I feel that the optimization process is happening on the board,” he says. Solving a problem that he understands - chess - he can get an idea about the one he doesn’t know, for example, about proteins. “If the knight’s move is not optimal, AlphaZero can move him six positions to make it correct. If you play chess well enough, it is almost the same as if you felt that this was the right move. It's like being inside the AlphaZero mind. ”

With Hassabis, naturally, plans are not limited to the mere saving of millions on pharmaceutical research. He believes that in the future, AI could learn how to work as a scientist, develop hypotheses and develop experiments to test them, and then "make a major breakthrough of the Nobel Prize level."

Sometimes, between the dreams of Stockholm and the analysis of chess games, reality blasts roughly. One of the company's projects includes an analysis of health data. Pattern recognition, which allows you to determine the best response to the late castling on the part of the queen, can also recognize the diagnosis of, say, an early manifestation of retinal disease symptoms. However, to make such a diagnosis DeepMind needs a lot of data - it needs access to records of NHS patients.

People started to notice it. In 2017, the Information Commissioner condemned the Royal Free Hospital for not doing enough to inform patients about the partnership before transferring the data to DeepMind to process this data on its behalf. Just last month, it was announced that the company's subsidiary would go to Google, which would require additional guarantees that patient data in the UK would be protected.

Problems of this kind are inevitable and they will continue, penetrating even into the rarefied atmosphere of Plato's room into DeepMind (the “cave” - basically, like other rooms, but with bean bags). Most of them will be solved - some of them by the company itself, others by the society adapting to the new world of big data and algorithms.

The problem, which is unlikely to ever disappear, is also one of the most important. Instead of wondering if we can develop true artificial intelligence, some argue that we should start worrying about whether we should develop it.

Hassabis, like everything else in this area, has a rehearsed answer to a question that can be described as “the problem of the apocalypse of robots”. He is positioning himself as a person in a measure of concern, but not exaggerating the facts. There are ethical problems with artificial intelligence, but they can be solved, and the difficulties that it can solve are much more significant than the difficulties that it can cause.

“I would be much more pessimistic about the future if I didn’t know that artificial intelligence is on its way,” he says. “There are so many problems, from Alzheimer's disease to climate change, that are extremely complex and in solving which we seem to be making little progress. Either we need an exponential improvement in human behavior or an exponential improvement in technology, and the world does not look as if it is acting on the first principle. ”

At the moment, however, he is not obsessed with the apocalypse. Instead, he enjoys an achievement that concerns both the past and the future. At the age of 13, young Demis Hassabis made the calculation. He threw chess, although he knew that he had a chance to become the best chess player in the world.

Then he chose a path that, he admits, seems completely random. And yet, like a chess knight who made six moves to get to the right place to attack, he walked towards something that was somehow inevitable from the very beginning.

This path led him to today where, being in a room in his office, where extremely interested grandmasters work, he created the best chess player in the world. “I have come full circle. I am the world champion in the game of chess "by proxy". I think if you talk about it like Freud, ”he says,“ maybe I had some unfinished business. ”

Checkmate.