MIT course "Security of computer systems". Lecture 23: "The Economics of Security", part 3

- Transfer

- Tutorial

Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Lecture course # 6.858. "Security of computer systems." Nikolai Zeldovich, James Mykens. year 2014

Computer Systems Security is a course on the development and implementation of secure computer systems. Lectures cover threat models, attacks that compromise security, and security methods based on the latest scientific work. Topics include operating system (OS) security, capabilities, information flow control, language security, network protocols, hardware protection and security in web applications.

Lecture 1: “Introduction: threat models” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 2: “Control of hacker attacks” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 3: “Buffer overflow: exploits and protection” Part 1 /Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 4: “Privilege Separation” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 5: “Where Security System Errors Come From” Part 1 / Part 2

Lecture 6: “Capabilities” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 7: “Native Client Sandbox” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 8: “Network Security Model” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 9: “Web Application Security” Part 1 / Part 2/ Part 3

Lecture 10: “Symbolic execution” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 11: “Ur / Web programming language” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 12: “Network security” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 13: “Network Protocols” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 14: “SSL and HTTPS” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 15: “Medical Software” Part 1 / Part 2/ Part 3

Lecture 16: “Attacks through a side channel” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 17: “User authentication” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 18: “Private Internet viewing” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 19: “Anonymous Networks” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 20: “Mobile Phone Security” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 21: “Data Tracking” Part 1 /Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 22: “MIT Information Security” Part 1 / Part 2 / Part 3

Lecture 23: “Security Economics” Part 1 / Part 2

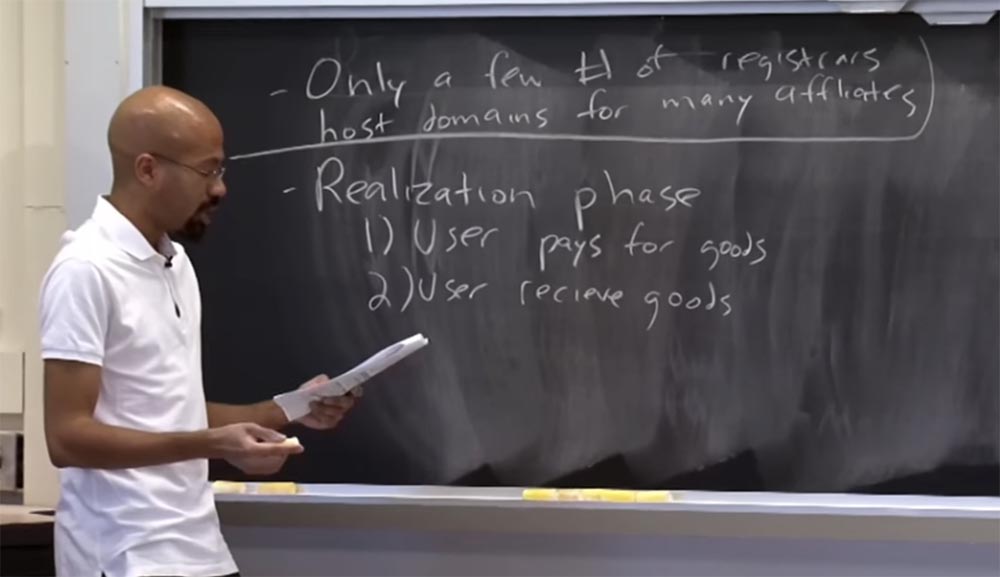

The lecture article talks about various retaliation strategies that can stop a spammer. The authors noticed that there is a limited number of domain name registrars for affiliate programs. This means that the majority of affiliate partners are individually associated with the registrar who deals with their domain names and infrastructure. It is very rare when one domain name registrar is associated with a bunch of different affiliate programs.

This means that there is no common center, common registrar, striking a blow at which one could disable the entire spam infrastructure. A similar scheme applies to things like web servers. It’s rare for one ISP provider to own a bunch of web servers with a bunch of affiliate programs. This business has a distributed nature, so it is very difficult to say that if we “take” these 3 providers, the entire spam ecosystem will be destroyed.

Therefore, it is a pity that there is no single server that could be hit to stop spamming. Later we will see that this may work in relation to some shadow banking schemes, so maybe we can still put pressure on the spammer.

Let's go back to reviewing the spam implementation stage and see what happens after you, the user, decide to buy something. The implementation phase consists of two parts.

The user pays for any goods that he buys or wants to buy, and then, I hope, receives these goods either by mail, as in the case of buying fake drugs, or downloads from the Internet if he wants to get a pirated Photoshop or something like that.

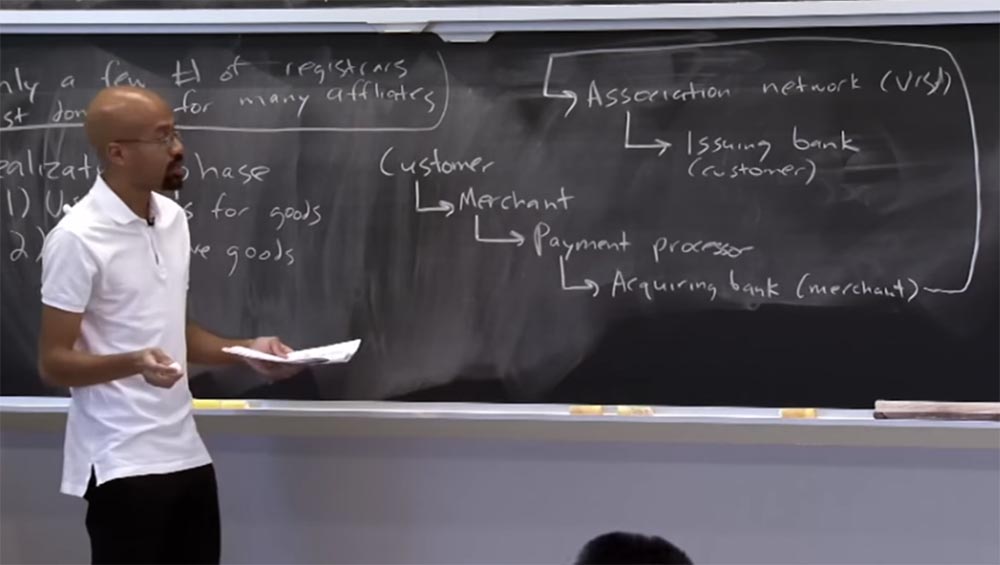

Cash flow looks like this. The customer turns to the seller and tells him that he wants to buy something. It sends credit card information, after which the merchant communicates with the payment processor. This is an important mediator who helps the seller, the spammer, to deal with some of the subtleties of interaction with the credit card system. The payment processor is associated with the service bank.

The servicing bank carries out all operations related to the execution of settlements and payments by bank cards. He associates himself with what is called an “associated network” in the article, but we will think of it simply as a Visa or MasterCard payment system, so these are just credit card networks.

Finally, these Association networks, or card networks, communicate with the issuing bank of the buyer. In fact, they ask for information whether the transaction is legal, that is, it happens with the consent of the cardholder. If so, the money goes through the whole system and goes to the seller. This is what the end-to-end financial workflow looks like. This workflow can handle a lot of money. One of the articles mentioned in the lecture material says that one partner can receive more than $ 10 million dollars as a result of such a transaction. The question arises why the acquiring bank or the issuing bank will not report that there is something wrong here? As it turns out, in many cases they don’t really report anything.

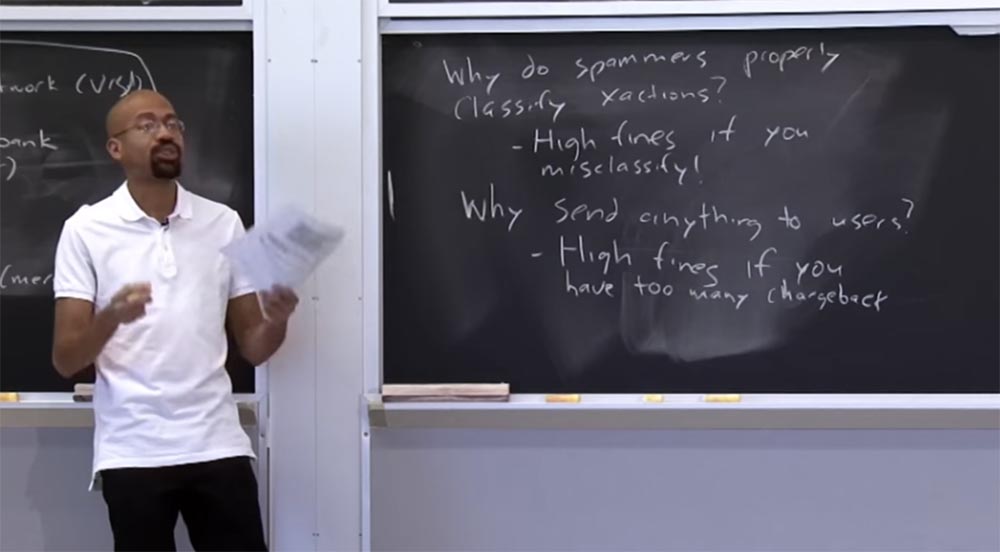

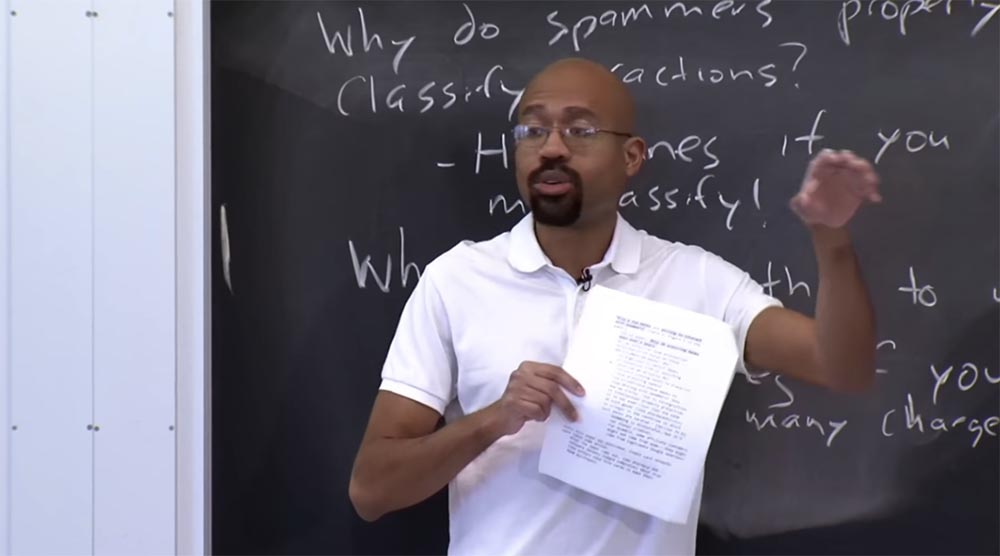

I wonder why the financial system tolerates such processes. For example, why do spammers correctly classify their transactions? When you want to send something through this system, you must correctly identify the type of transaction being conducted, indicating that you sell pharmaceuticals, software, anything, it does not matter. It can be assumed that a spammer selling fake vitamins will not want to indicate that he is in the pharmaceutical business. However, it is interesting that spammers in most cases correctly classify transactions. The reason is that for a wrong classification may award a high fine.

Therefore, associated networks such as Visa or Mastercard consider that everything is in order with such transactions, even if they look a bit suspicious. But they do not want to be accused of money laundering or trying to deceive the authorities. As long as you properly classify what you are doing, then you are in a certain sense defending yourself. Because you can always tell the authorities that you did not understand the law a bit, but at least you did not try to hide the purpose of this transaction. Thus, spammers often correctly classify their transactions, that is, they play a certain measure within the system.

Another question I mentioned earlier is why should a spammer send something to customers? Presumably, if you're a spammer, then you're a criminal, right? So why not just collect money from the people and not run away with them? It turns out that they actually send things to customers, because they do not want to run into heavy fines. This is a very interesting system in which spammers want to do something legally, and while they still cannot use bitcoins, they actually have to work within the constraints of an already existing system.

High fines are also awarded if the spammer has a lot of chargebacks. Refundable payment means that the client declares to the financial company that he did not receive the paid goods or the quality of the goods received does not suit him. Therefore, if a spammer has too many clients demanding a return of payments, very, very high fines are levied on him. Therefore, the percentage of chargeback for spam deals is quite small. The fact is that the conversion rates of their profits are super low, so even one or two fines can destroy the entire monthly profit. So spammers are really interested in avoiding fines in both of the above cases.

Audience: Does PayPal use a more hidden bank relationship?

Professor:Yes and no. PayPal is in many ways very similar to Visa or MasterCard. Its activity is governed by similar rules, because these payment systems have the same types of risks. I think that some things Visa has more stringent restrictions, which we will discuss in a second. But as a payment system, Paypal has similar goals.

Audience: is there an idea to organize a group in which you create an account, and then intentionally go to the spammer's website, buy a bunch of things, and then make repayments to collect a fine? Or report that spammers misclassify transactions so that they are fined?

Professor: interesting idea, just like vigilantes!

Audience: yes, spam spammers.

Professor:Yes, exactly, but I have never heard of it. I know that spammers are trying to find people who troll them. The article says how the authors identified spammers. They received a bunch of spam messages, went through a bunch of links, issued a special Visa card that they used to buy these things, and so on. They call it "test purchases." However, spammers tend to prevent test purchases of people trying to figure out what is going on. Therefore, some spammers require you to confirm your identity before you sell something. They may ask you to send a photo of your ID card or something like that. Some people began to do this after Visa tightened the rules regarding spam. Now spammers have problems because people who click on spam links, They do not want to send a scan of their identity to some random person. The article contains excerpts from the correspondence of spammers on the forum, where they complain that Visa got them - they have to ask people to send them a personal identification, but they don’t want to do that. It is strange that people are afraid of sending scans of documents to spammers, but they are not afraid to tell them their credit card numbers. In any case, spammers are interested in timely detection of people trying to bring them to clean water. but don't be afraid to give them your credit card numbers. In any case, spammers are interested in timely detection of people trying to bring them to clean water. but don't be afraid to give them your credit card numbers. In any case, spammers are interested in timely detection of people trying to bring them to clean water.

Audience: with regard to chargebacks - perhaps if people do not want their bank to know that they are buying illegal items, then they will hesitate to demand a refund even if they did not receive the goods?

Professor: good question. I do not know how many people who bought all sorts of dietary supplements were disappointed by them and reported this to their bank. Interestingly, the bank must first of all know where it directs the money, but I think you do not need to disclose any additional information about the transaction to it in order to issue a refund.

Audience: What percentage of chargebacks make a spammer anxious?

Professor:Call numbers on the order of 1% of all transactions. In other words, if you are a spammer and you have more than 1% of transactions require a refund, this is a cause for concern. I would not be surprised at the lower numbers, but I heard exactly about one percent.

As I have already said, for me it was one of the most interesting parts of the article, because I always believed that open fraud was a mandatory feature of spam. That is, people went through the links, sent the money and did not receive anything. But as it turned out, spammers have to go through this entire network, which has mechanisms to prevent fraud, and ultimately they have to send things to customers.

Another reason spammers choose to act carefully, classify transactions correctly and actually send things to customers is that only a few banks are willing to cooperate with spammers. This means that if a spammer receives a lot of chargebacks, or creates problems with banking operations and credit cards, then some bank can break off relations with it. At the same time there are not so many other banks that agree to meet the spammer, so that he continues to deal with his "pranks".

Research on this topic has shown that there are only about 30 acquirers, whose services spammers have used for more than two years. In fact, this is a very small number of banks. So the lack of banks serves as an incentive not to fool with the financial system, because the spammer simply has no one to turn to if he breaks the established partnership.

Thus, it seems that the requirements of strict adherence to financial rules can reduce spam. We discussed that things like a botnet provide a lot of IP addresses to spammers, there are enough providers ready to run web servers for them and so on, but the number of servicing banks actually seems small. So maybe we can really attack spam right here.

But, as I have already said, this is difficult to do because it is difficult to prove the fact of the illegality of spamming. For example, if you use spam messages to sell, say, sugar, there is nothing illegal in it, because selling sugar does not violate any laws. You can somehow deceive the buyer in the sale process, but the sale of sugar itself is not illegal.

As it turns out, a lot of spam falls into this “gray area”, where the things that spammers make can be unpleasant, but it does not necessarily violate the law. For things like pirated software, legislation more clearly delineates the limits of legality. However, you cannot simply point to one of these banks and say “hello, your customers are criminals!” Because this is not always true, especially if there is no clear paper evidence that links the financial transaction to the URL of the spammer is the origin of this transaction. It is often very difficult to prove the connection of these links in the spamming chain.

Since the article under review was published, the credit card industry has taken some response, because this article created quite a stir at the time of its release. After that, the associations of payment systems Visa and MasterCard wondered what they could do to cut off some of the spam. Interestingly, after the article was published, some pharmaceutical companies and software vendors filed complaints against Visa.

If you remember from the article, Visa was an associated network through which spam researchers made trial or bogus purchases, so some companies felt that Visa could be used as a system for financing spammers and decided to complain about it.

In response to these complaints, Visa has made some changes to its payment policy. For example, now all transactions with pharmaceutical products Visa marks as high-risk sales. This means that if the bank acts as an acquirer for these transactions, then Visa will establish more stringent transaction conditions for it, for example, it will require the bank to participate in the risk management program or will check it more often.

Visa also changed its internal regulations. Now they have unequivocally defined the list and banned the illegal sale of medicines and goods that are protected by registered trademarks.

This helps to introduce more aggressive fines against banks and merchants who, in the opinion of this payment system, are involved in the illegal sale of drugs, watches of counterfeit brands and so on. I repeat once again - there is still a lot of spam in the “gray area”, and this is not necessarily illegal. It is just that customers are required to use certain techniques. But now Visa can have a greater impact on people.

To avoid fake purchases, which are not only for spam researchers, but also for associated networks, spammers began to require identity scans from buyers, and this is usually not very good.

At least a few years after the payment systems made changes to the rules for conducting transactions, this had an impact. Nice to see that this article has had a big impact on real life.

Another interesting thing that is mentioned in the article is the ethical aspects of conducting security research, in particular, spam chain research. To understand how some of the banking mechanisms work, researchers actually had to make purchases. They had to pay the spammer for these goods. The authors write that they destroyed everything they bought without using anything, and talked with software companies about buying pirated versions of their software before buying it.

In fact, the origin of such things is of great importance, especially in a university environment. Because if you want to do something that includes personality research, everything that may have ethical aspects, you must get permission from lawyers from the Ethical Assessment Commission of IRB research projects and the like. It is very important for researchers to be sure that by their actions they will not support intruders in some remote corner of the world. This is also an interesting part of the lecture materials, because we have already discussed how ethical it is to develop zero-day exploits if you know that they cannot be corrected by someone? So this is a really interesting aspect of security research.

Lecture hall:Is there any oversight of security ethics? Because the article says that the IRB is not interested in this.

Professor:Yes, it was very interesting. They argue that the IRB was not interested, I think, because there was no obvious human subject in these studies. However, for most universities, one cannot simply say that there is no direct human subject, so just let me buy some spam links. In the article, they express appreciation to various people and organizations who have assisted in conducting research. I do not think that there is any American standard for this type of research. I know that the IRB of each university has a slightly different policy regarding what can and cannot be done, so I do not think that there is any general policy.

Lecture hall:If we consider that 350 million spam addresses were tracked, and only 28 contacted spammers, is there a possibility that a significant number of these 28 were researchers who studied the chain of spam?

Professor: I think that these results were one of the reasons why the authors made so much effort to protect themselves from accusations of bias. Because if you think about how fun this statistic is, where adding 5 or taking five will actually affect whether a spammer can give his children a real gift or give them a piece of coal, because there were so few good purchases.

As for the specific number of people hooked to the spammer, I do not know how many of them were researchers. But I think that in general, as I said, spammers just want to take your money. And therefore, if they could find some kind of balance in which researchers can test the purchase of goods without affecting the total number of sales, it would be great for spammers, because the main thing for them is to get money, anyway, with who

The difficulty is that we suppose that 35 purchases were made, of which half were made by researchers, as a result of which people put pressure on banks, after which spammers made only 2 sales instead of 35 - that’s what they don’t want. Therefore, spammers are interested in stopping such research.

Lecture hall:How many of these 350 million messages are filtered? I’m sure that it’s not a problem for a spammer to send out 350 million spam messages.

Professor: it’s all about cost-benefit analysis from the spammer’s point of view. I think that there is a market for the purposeful implementation of such things. In particular, hacked email accounts become very useful because spammers are more likely to influence the target audience and view focused spam emails as promising higher profits. For example, spam focused on the preferences of a particular social group, suppose a group of followers of the Dalai Lama.

Audience: it would be interesting if there was a company looking for gullible grandmothers to insert spam into their letters.

Professor: I would not be surprised if such things exist, but I do not know about it. The last thing I would like to tell you about is companies that have taken on the responsibility of doing things they call hackback, or “hacking back”. The idea is that if you are a bank and someone is trying to hack you and steal information, then you yourself find these hackers and deal with them in the same way.

For example, in response to their attack, you are trying to disable their botnet, or steal their information, or do something similar. Today it is more common than before. One of the reasons is that the legal system is slowly adapting to some modern threats, and banks or financial institutions are tired of waiting for effective measures from it. For example, in 2013 there was a huge network of botnets to distribute pirated software and counterfeit goods, so a huge coalition of Microsoft companies, American Express, Paypal, many of which launched a botnet destruction operation, was formed to take countermeasures. In fact, they themselves, without resorting to the help of government structures, destroyed the pirate botnet. They lurked for a while and found out where the Command & Infrastructure is located. Control. Then they captured it, determined where all the end-user bots were and sent messages informing users about the need to patch their computers.

This example is very interesting from the point of view of the intersection of computer security interests and laws, because some sections of US law give companies the right to do this. For example, Microsoft lawyers said that these botnet networks violate the rules for using the Microsoft trademark.

For example, if you sell pirated copies of Windows and claim that it is Windows, without obtaining the right to dispose of these copies legally, and you cannot legalize the sources of their origin, then Microsoft claims violation of the right to trademark and its reciprocal right hack your network botnet. In this sense, there is a certain overturn of logic, but the court allowed it. And this happens more and more often.

Most of all this situation melts the banks, because they note some kind of state sponsorship of hacking banking systems. Since bankers care about money, they get very upset when they lose it.

It is therefore interesting to see how the burden of ensuring cybersecurity, in particular, offensive operations, is shifting to the private sector, because the long-term consequences of such a decision seem not entirely clear.

That's all, I think that we will see you on Wednesday on reviewing your presentation projects on the results of this course of lectures.

Full version of the course is available here .

Thank you for staying with us. Do you like our articles? Want to see more interesting materials? Support us by placing an order or recommending to friends, 30% discount for Habr's users on a unique analogue of the entry-level servers that we invented for you: The whole truth about VPS (KVM) E5-2650 v4 (6 Cores) 10GB DDR4 240GB SSD 1Gbps from $ 20 or how to share the server? (Options are available with RAID1 and RAID10, up to 24 cores and up to 40GB DDR4).

VPS (KVM) E5-2650 v4 (6 Cores) 10GB DDR4 240GB SSD 1Gbps until January for free if you pay for a period of six months, you can order here .

Dell R730xd 2 times cheaper? Only here2 x Intel Dodeca-Core Xeon E5-2650v4 128GB DDR4 6x480GB SSD 1Gbps 100 TV from $ 249 in the Netherlands and the USA! Read about How to build an infrastructure building. class c using servers Dell R730xd E5-2650 v4 worth 9000 euros for a penny?