Xiangqi: Chinese chess game

If you visit China and decide to look at the life of ordinary Chinese, then you will definitely come across such a picture.

Men enthusiastically play a board game in appearance resembling ... checkers. Yes, yes it is CHECKERS, but you are mistaken, this game is a chess type. Before us is the classic confrontation between two armies of figures of different ranks.

Many European researchers call this game CHINESE CHESS, which in my opinion is not entirely true. This is XIANCI, a Chinese chess game with a long history and unique identity.

Western scholars usually see xiangqi as one of the branches of the development of the class of games, the root of which is shaturanga (chaturanga). According to this version, it is believed that the shaturanga (chaturanga) is the common ancestor of all chess games known now. Moving west, the shaturanga (chaturanga) gave rise to the Arab shatranj, which became the ancestor of modern classical chess. Spreading east and reaching China, the shaturanga (chaturanga), and possibly even the shatranj, were modified in accordance with Chinese traditions and turned into xiangqi.

Here is how Robert Bell describes the emergence and purpose of the game in his book: “Shatrange has undergone significant changes in a new form, and already elephants, horsemen, foot soldiers, a cannon with war chariots fought for the capture of the enemy general. Each army had a fortress, sitting in which the general and his tangerines hatched their plans. To win the party, it was necessary to storm the enemy’s fortress. A river flowed between the two armies, which heavy elephants could not overcome. Other light figures freely forced her. ”

Chinese scholars strongly disagree with the theory of the origin of Xiangqi from shaturanga (chaturanga). Based on documents, the oldest of which date back to the Han era, they claim that the game, which became the ancestor of Xiangqi, appeared in ancient China about 3,500 years ago and was originally called ANYWHERE. In this game, chips were also moved along the board, among which there were pawns and a general with different rules of the move, but they used dice to determine the move, thus introducing an element of randomness into the game. Just like the progenitor of shaturanga (chaturanga) was the game TAAYAM. Later, the bones were abandoned, having received the game of GEUILI SAYZHZHAN.

In the era of the Tang, the rules of the game were modified, and the variety of figures was increased, which led to the emergence of the rules of the Xiangqi, close to modern. It was definitely proved that in the 8th century China had XIANCI, two players played in it, the dice were no longer used, and the set of figures corresponded to the set of figures of the shaturanga (chaturanga) - general (king), horse, elephant, chariot (boat) and soldiers (pawns).

So consider the game itself.

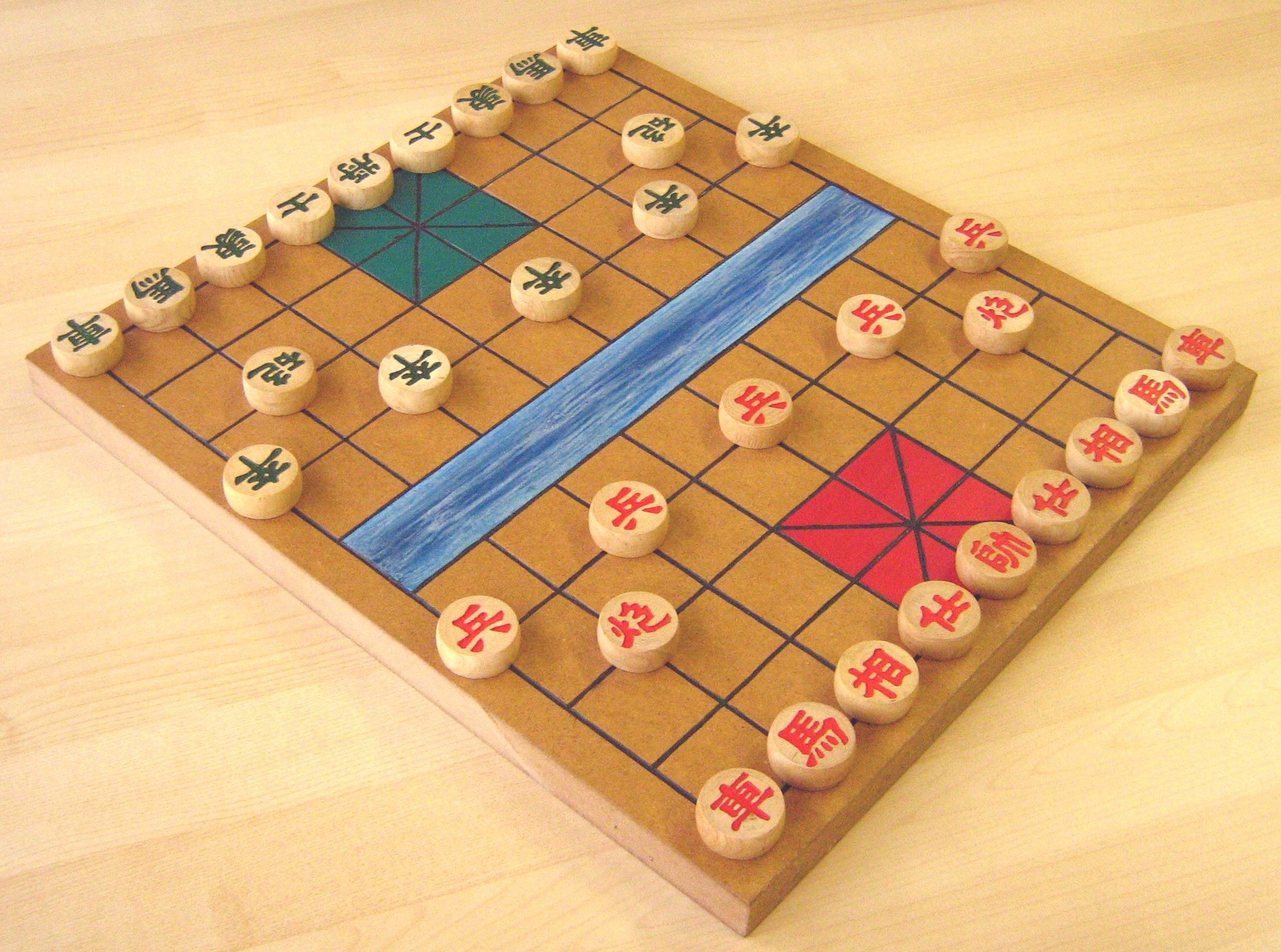

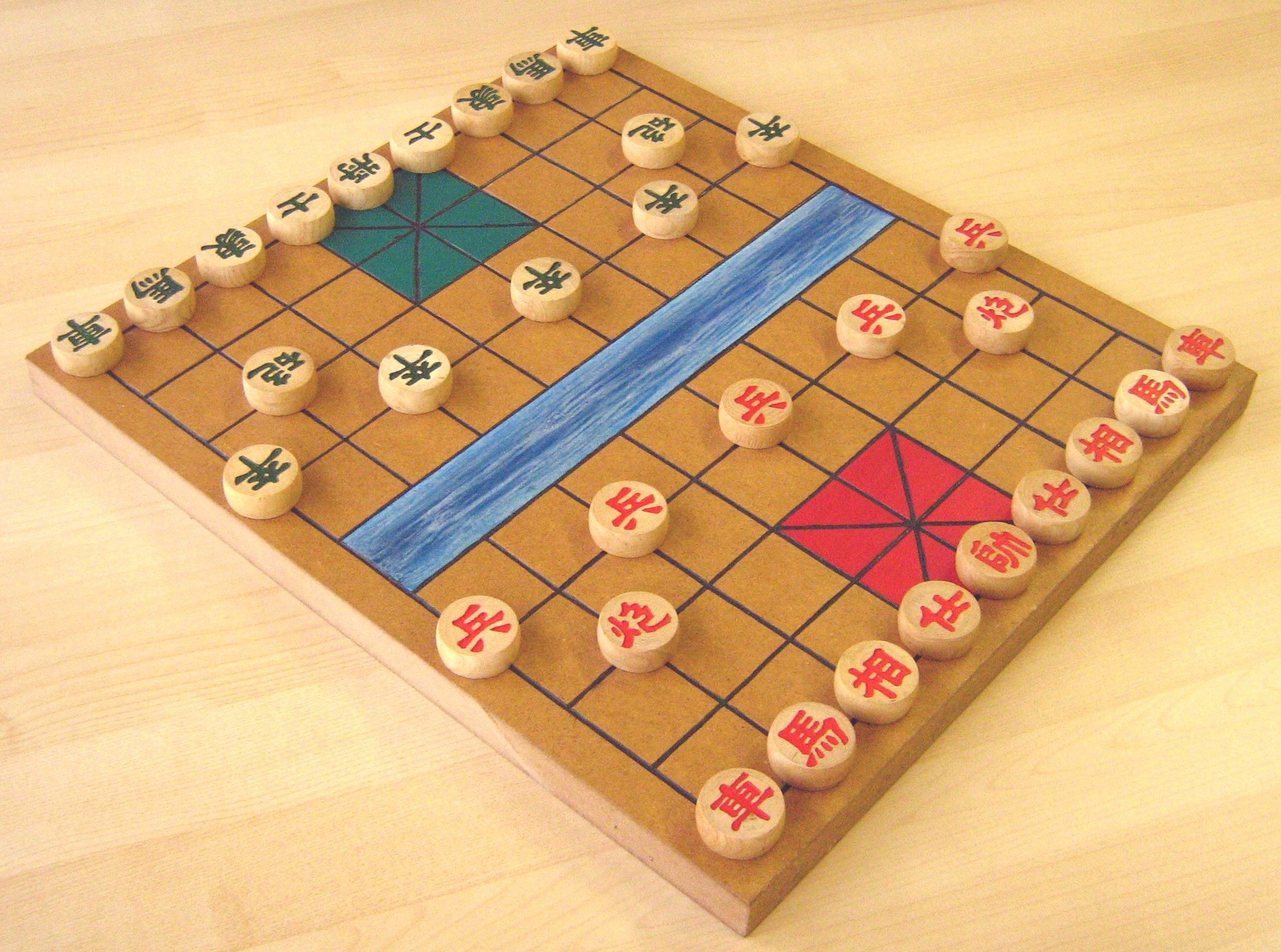

The XIANCI game board consists of two halves with 8 by 4 squares, which are separated by a space of one square width, known as the RIVER (or POND). Each half of the board has four squares marked with diagonals, thus formed a square of nine points represents a FORTRESS (LOCK). When playing, the figures are placed at the intersections of the lines, and not in the squares themselves. Therefore, the board is considered as one large space of points in the amount of 9 to 10.

In the classic game, the pieces are round disks of the same size. On the upper side of the figure is written its meaning. Typically, labels are made in red and green (sometimes black) color. When writing equivalent figures, various Chinese characters are used to denote them, for example, if on some figures the inscriptions were in English, and on others - in German.

The following figures are presented on the game board in the SYNCI (taking into account the rules for their movement during the move):

GENERAL for the "green" ("black") / MARSHAL for the reds - a piece similar to the chess KING, his loss means losing the player in the game. It can move one point in the vertical or horizontal direction, but in its movements it is limited to nine points of its fortress (castle). Generals cannot look at each other face to face (when there are no pieces between them in a vertical line), in this case, in response to the move that frees the line, the general can attack through the whole field and kill the enemy general with his “look” (a very funny rule with oriental flavor, images from Chinese historical films with piercing looks of actors playing the role of some generals immediately come to mind).

GOVERNOR for the "green" ("black") / Mandarin for the red - the piece can move one point diagonally, but they are also limited in their actions by the borders of the fortress, i.e. five dots marked in bold lines.

Bishop for the “green” (“black”) / MINISTER for the red - the figure can go diagonally to only one next point, except that the figure cannot cross the river (pond) and invade enemy territory.

HORSE / HORSE - a figure can move one point vertically or horizontally with subsequent movement to a point diagonally. Unlike a chess knight, a knight in xiangqi is an ordinary linear piece - during the move he does not “jump” from the starting point to the final one, but moves in the plane of the board, first horizontally or vertically, and then diagonally. If at the intermediate point of the horse’s move there is its own figure or the opponent’s, then it blocks the corresponding move.

Chariot / Rook - an analogue of a chess rook, can move any distance vertically or horizontally.

CATAPULT for the "green" ("black") / GUN for the red - can walk like a chess rook. It captures enemy figures only if there is some third figure called the screen between it and the attacked figure.

WARRIOR / Pawn - on its half of the board it can only go vertically one point forward, in the territory of the enemy it can move one point forward or sideways. When reaching the opponent’s back line, he can only move horizontally. The ability to transform into other pieces, like in chess, does not possess.

The goal of the game is to declare MAT to an enemy general or achieve a stalemate. At the same time, the player cannot give an eternal check, he must vary his moves.

The general is under the check under the following conditions:

- being attacked by any figure, he can be captured during the next move, if measures are not taken to repel an attack on him;

- when the generals oppose each other on the same vertical and there are no figures between them (that same piercing look).

When a shah is declared to the general, three answers are possible:

- the attacking general’s figure can be taken by the opponent’s figure;

- the general may withdraw from the shah;

- the check can be averted using “specific” rules for the movement of pieces (for example, add / remove the screen in front of the cannon, fend off / block the rider).

Unfortunately, in our country and in Europe, the Xiangqi could not achieve great popularity, although this is the most popular game in China (there is a game in almost every house). But there are objective reasons for this:

Firstly, in order to understand the figures themselves, it is necessary to understand Chinese characters at least at the initial level and be able to read the characters marked on them.

Secondly, there is practically no translated professional literature on this topic (dissimilar articles, including this one) that will not allow full penetration into the world of this fascinating game.

Now a lot is being done to popularize this game, for example, you can buy just such a set with figures close to chess.

Or here’s such a souvenir set of the Xiangqi game in ethnic style

Before writing this article I personally “crossed” the expanses of various markets and found some wonderful Xiangqi game simulators for IOS and Android to get an idea about it.

For the sake of interest, I suggest you enter “xianqi”, “xianci” or “xiangqi” in the search engine to try yourself in this game.

I hope, given the growing interaction between Russia and China, more literature will begin to appear in Russian, not only on the history of this game, but also with clarifications of the rules and examples of parties.

Men enthusiastically play a board game in appearance resembling ... checkers. Yes, yes it is CHECKERS, but you are mistaken, this game is a chess type. Before us is the classic confrontation between two armies of figures of different ranks.

Many European researchers call this game CHINESE CHESS, which in my opinion is not entirely true. This is XIANCI, a Chinese chess game with a long history and unique identity.

Western scholars usually see xiangqi as one of the branches of the development of the class of games, the root of which is shaturanga (chaturanga). According to this version, it is believed that the shaturanga (chaturanga) is the common ancestor of all chess games known now. Moving west, the shaturanga (chaturanga) gave rise to the Arab shatranj, which became the ancestor of modern classical chess. Spreading east and reaching China, the shaturanga (chaturanga), and possibly even the shatranj, were modified in accordance with Chinese traditions and turned into xiangqi.

Here is how Robert Bell describes the emergence and purpose of the game in his book: “Shatrange has undergone significant changes in a new form, and already elephants, horsemen, foot soldiers, a cannon with war chariots fought for the capture of the enemy general. Each army had a fortress, sitting in which the general and his tangerines hatched their plans. To win the party, it was necessary to storm the enemy’s fortress. A river flowed between the two armies, which heavy elephants could not overcome. Other light figures freely forced her. ”

Chinese scholars strongly disagree with the theory of the origin of Xiangqi from shaturanga (chaturanga). Based on documents, the oldest of which date back to the Han era, they claim that the game, which became the ancestor of Xiangqi, appeared in ancient China about 3,500 years ago and was originally called ANYWHERE. In this game, chips were also moved along the board, among which there were pawns and a general with different rules of the move, but they used dice to determine the move, thus introducing an element of randomness into the game. Just like the progenitor of shaturanga (chaturanga) was the game TAAYAM. Later, the bones were abandoned, having received the game of GEUILI SAYZHZHAN.

In the era of the Tang, the rules of the game were modified, and the variety of figures was increased, which led to the emergence of the rules of the Xiangqi, close to modern. It was definitely proved that in the 8th century China had XIANCI, two players played in it, the dice were no longer used, and the set of figures corresponded to the set of figures of the shaturanga (chaturanga) - general (king), horse, elephant, chariot (boat) and soldiers (pawns).

So consider the game itself.

The XIANCI game board consists of two halves with 8 by 4 squares, which are separated by a space of one square width, known as the RIVER (or POND). Each half of the board has four squares marked with diagonals, thus formed a square of nine points represents a FORTRESS (LOCK). When playing, the figures are placed at the intersections of the lines, and not in the squares themselves. Therefore, the board is considered as one large space of points in the amount of 9 to 10.

In the classic game, the pieces are round disks of the same size. On the upper side of the figure is written its meaning. Typically, labels are made in red and green (sometimes black) color. When writing equivalent figures, various Chinese characters are used to denote them, for example, if on some figures the inscriptions were in English, and on others - in German.

The following figures are presented on the game board in the SYNCI (taking into account the rules for their movement during the move):

GENERAL for the "green" ("black") / MARSHAL for the reds - a piece similar to the chess KING, his loss means losing the player in the game. It can move one point in the vertical or horizontal direction, but in its movements it is limited to nine points of its fortress (castle). Generals cannot look at each other face to face (when there are no pieces between them in a vertical line), in this case, in response to the move that frees the line, the general can attack through the whole field and kill the enemy general with his “look” (a very funny rule with oriental flavor, images from Chinese historical films with piercing looks of actors playing the role of some generals immediately come to mind).

GOVERNOR for the "green" ("black") / Mandarin for the red - the piece can move one point diagonally, but they are also limited in their actions by the borders of the fortress, i.e. five dots marked in bold lines.

Bishop for the “green” (“black”) / MINISTER for the red - the figure can go diagonally to only one next point, except that the figure cannot cross the river (pond) and invade enemy territory.

HORSE / HORSE - a figure can move one point vertically or horizontally with subsequent movement to a point diagonally. Unlike a chess knight, a knight in xiangqi is an ordinary linear piece - during the move he does not “jump” from the starting point to the final one, but moves in the plane of the board, first horizontally or vertically, and then diagonally. If at the intermediate point of the horse’s move there is its own figure or the opponent’s, then it blocks the corresponding move.

Chariot / Rook - an analogue of a chess rook, can move any distance vertically or horizontally.

CATAPULT for the "green" ("black") / GUN for the red - can walk like a chess rook. It captures enemy figures only if there is some third figure called the screen between it and the attacked figure.

WARRIOR / Pawn - on its half of the board it can only go vertically one point forward, in the territory of the enemy it can move one point forward or sideways. When reaching the opponent’s back line, he can only move horizontally. The ability to transform into other pieces, like in chess, does not possess.

The goal of the game is to declare MAT to an enemy general or achieve a stalemate. At the same time, the player cannot give an eternal check, he must vary his moves.

The general is under the check under the following conditions:

- being attacked by any figure, he can be captured during the next move, if measures are not taken to repel an attack on him;

- when the generals oppose each other on the same vertical and there are no figures between them (that same piercing look).

When a shah is declared to the general, three answers are possible:

- the attacking general’s figure can be taken by the opponent’s figure;

- the general may withdraw from the shah;

- the check can be averted using “specific” rules for the movement of pieces (for example, add / remove the screen in front of the cannon, fend off / block the rider).

Unfortunately, in our country and in Europe, the Xiangqi could not achieve great popularity, although this is the most popular game in China (there is a game in almost every house). But there are objective reasons for this:

Firstly, in order to understand the figures themselves, it is necessary to understand Chinese characters at least at the initial level and be able to read the characters marked on them.

Secondly, there is practically no translated professional literature on this topic (dissimilar articles, including this one) that will not allow full penetration into the world of this fascinating game.

Now a lot is being done to popularize this game, for example, you can buy just such a set with figures close to chess.

Or here’s such a souvenir set of the Xiangqi game in ethnic style

Before writing this article I personally “crossed” the expanses of various markets and found some wonderful Xiangqi game simulators for IOS and Android to get an idea about it.

For the sake of interest, I suggest you enter “xianqi”, “xianci” or “xiangqi” in the search engine to try yourself in this game.

I hope, given the growing interaction between Russia and China, more literature will begin to appear in Russian, not only on the history of this game, but also with clarifications of the rules and examples of parties.