Engineers have created a flexible sensor that mimics the skin

The joint work of American engineers from Stanford University and the Palo Alto Research Center led to the creation of a sensor on a flexible basis that can distinguish between pressing force. The sensor sends out electrical impulses similar to those coming from the skin - while, like the skin, their number increases with the force of pressing. This material will be used to create new-generation prostheses.

As the study leader explainsProfessor Zhenan Bao, the main advantage of the sensor is that it emits impulses that the nervous system can process directly. According to him, pressure sensors have already been created for prostheses, but the impulses issued by them were not in the format in which the brain could perceive them. In this regard, the prosthesis needed a computer to convert signals.

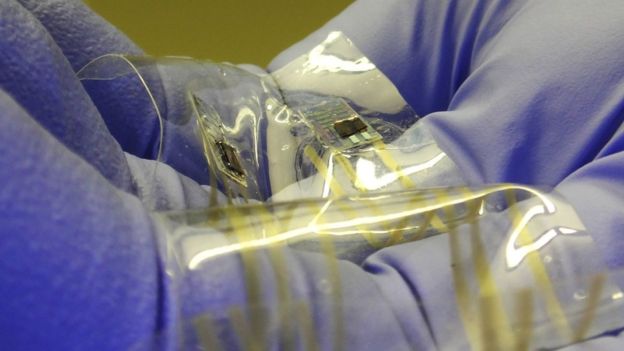

The new sensor is equipped with a simple electronic circuit, allowing you to issue pulses of the desired format. Since the sensors are located on flexible and extensible material, they can also be useful in wearable electronics. For example, fixing them on clothes, you can use them to read the heartbeat or pressure.

One of the sensor layers is made of a polymer penetrated by carbon nanotubes and formed in the form of pyramids. When the flexible base is compressed, the pyramids are deformed, which leads to a change in the conductivity of the compressible area. And under this layer is a printed circuit of an oscillator that converts alternating current into a train of pulses. The larger the press, the greater the current and the faster the pulses go.

To demonstrate the capabilities of the sensors, Professor Bao associates applied the achievements of optogenetics , and converted the electrical impulses from the sensors into light. Experiments in mice whose brain cells have been modified appropriately have shown that neurons successfully respond to impulses transmitted in this way, even if their frequency reaches 200 Hz.

The problem with delivering pulses to the brain through electrodes is that hard electrodes damage neurons. Optogenetics allows you to act on neurons without coming into direct contact with them. In the future, it will be possible for such sensors to create optogenetic interfaces using genetic engineering, or to create soft electrodes that do not damage cells.