ITSM educational program: 7 ways to diagnose the causes of IT incidents and problems

- Transfer

Translation of a curious article by Stuart Raines, providing an overview of some approaches and techniques for finding the causes of incidents and problems. The review is superficial, but such a level of immersion is enough to generate interest in the subject.

Translation of a curious article by Stuart Raines, providing an overview of some approaches and techniques for finding the causes of incidents and problems. The review is superficial, but such a level of immersion is enough to generate interest in the subject. Author: Stuart Rance

Published on 10/31/2017 in the SysAid blog ITSM section

Link to the original: 7 Ways to Diagnose IT Incidents and Problems

It is necessary to train support staff and other IT personnel in the techniques of diagnosing incidents and problems, as well as to accompany their application. The presence of sufficient technical knowledge and work skills in ITSM processes without the skills of these techniques is not enough for the effective performance of diagnostic tasks.

Diagnostics of IT incidents and problems

Every IT organization has processes for managing incidents and problems. Often they are based on ideas from ITIL, whose best practice descriptions of IT service management are now most commonly used in the world. According to ITIL, an incident is “an unplanned interruption of an IT service or a deterioration in its quality ...”, and a problem is “any cause causing one or more incidents ...”. The goal of incident management is to restore the planned state of the service, and problem management helps reduce the consequences of future incidents.

Incident and problem management processes determine the steps that employees take to plan and implement tasks. As part of these steps, there is almost always one called “Examination and Diagnostics” (or something very similar to this), during which the magic of discovering the cause is accomplished.

For people whose job it is to correct the situation when something goes wrong, the most important thing is to identify the causes of errors and determine the result of a way to eliminate them. Of course, many other actions are performed within the process itself, such as keeping the information in the record of the appeal up to date and informing the user when there is a solution, but most of the time is spent on “Examination and Diagnostics”.

When we train IT support staff and other IT staff, we often send them to technical courses to be sure that they understand the technologies they work with, then we send them to ITIL courses (or other industry best practices) to be sure that they understand how processes work and how they fit in with other IT activities. But we very rarely really teach people how to examine and diagnose incidents and problems. Often a mentor is not even provided to give work skills to identify the causes of malfunctions. We believe that they already know how to do it. A very unfortunate fact is that in fact inexperienced personnel with a high probability have no idea how to approach these examinations and diagnostics, and really know what to do,

And so, whether you yourself perform the diagnosis of incidents and problems or manage those who make them, read on, where I will talk about the features of the approaches that allow us to solve these problems. Explore these approaches and you can apply them if necessary. The most useful practices will be presented, but their current list does not exhaust all possible options.

Diagnostic Approaches for Incidents and Problems

Some of the described approaches allow you to perform only diagnostics, while the rest can solve a wider range of tasks. Understanding all of their features will allow you to decide for yourself which approach is best suited in a particular situation.

1 Richard Feynman Approach

The famous physicist Richard Feynman proposed a process for solving physical problems, which is as follows:

- Describe the task

- Think hard

- to write an answer

This method is beautiful in its simplicity, but perhaps it will not work for those who are not smart enough to receive the Nobel Prize. So, I am sure that this approach can be used if you are VERY smart or working with a simple task and have access to all the knowledge and information that may be required. It is worth using this approach in conjunction with others, which will be discussed below, but think carefully before drawing conclusions - this is always a good practice.

2. Analysis of the history of observations

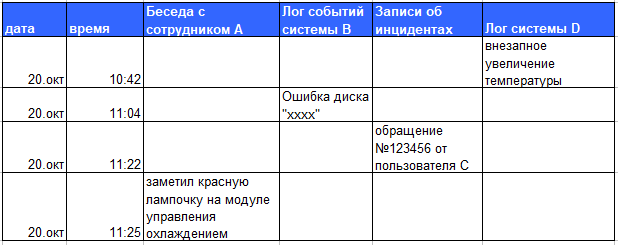

This is such an easy way to investigate an incident or problem that it’s hardly worth talking about. You just need to put on the timeline a list of everything that happened to the object of analysis and examine the resulting list. It is important that all received records contain, regardless of the data source, the date and time when the event occurred and are sorted by them. Your timeline may contain data from the logs of systems, letters, entries in the database of user requests and many other sources. This approach is surprisingly effective in building a general picture of what is happening.

Figure 1 - An example of the analysis of the history of observations.

I myself almost always start the survey with an analysis of the history of events, because this often allows us to understand what exactly happened, and also it allows us to obtain all the required information for applying more sophisticated approaches, if necessary.

3. Solving problems using the Kepner-Trego method

Despite the fact that I sincerely believe that this approach is extremely effective, according to the license agreement, when using this proprietary approach for training, I must voice my interest in it.

This is a structured approach to solving problems, in which a problem is defined through a number of different aspects (what, where, when, how much) and also connect the problem with aspects in which failures did not occur. And then you can see the difference with these specific possible situations.

Figure 2 - A simplified example of the use of problem solving by the Kepner-Trego method

4 Ishikawa diagram or fish skeleton

The Ishikawa diagram is a way to gradually eliminate the potential causes of problems. Reasons are grouped into categories and allow you to understand and visualize their relationships. You can create such charts to simplify the identification of all potential causes of problems during the diagnosis. And they can also be created as part of the product documentation, which makes it possible to immediately use them in solving any emerging issues.

Figure 3 - A simplified example of an Ishikawa diagram for an email service.

5. Knowledge oriented support

This is primarily a methodology for collecting and managing information that meets the needs of IT staff and Service Desk employees. If the requested information becomes available to someone who needs it, the time it needs, then this can lead to a quick awareness of what is happening and a quick solution to incidents and problems. And people with access to the right knowledge are much more likely to be able to use Richard Feynman’s problem solving method!

6. “Anthill” (Swarming)

This is a collective approach, different from the classical incident management, not only in the diagnostic phase, but also in many other aspects. There is no escalation to higher levels of support, and instead of a specific person who can help, participation in the “anthill” is included, which means there are many people from various parts of the organization who have an extensive range of relevant knowledge and skills for jointly resolving the issue. The Anthill may also apply some of the approaches described in this blog, but its key feature is the collaboration between many people with diverse skills, resulting in faster and more accurate diagnostics, as well as solving incidents and problems.

Read more about the “anthill” on this John Hall blog.

7. As always + on occasion (Standard + Case)

This is another approach in which many familiar aspects of incident management have been replaced. It was developed by Rob England and is described in this article and other publications that can be found by the name of the method. The main idea of the approach is that typical activities should be controlled by clearly defined processes, while more rare and complex (complex) ones require situational management using techniques developed in such areas as healthcare, social services, law and order policing. This technique is highly effective in incident management and at the same time provides a flexible approach to solving complex (complex) incidents.

Conclusion

It is necessary not only to train support staff and the rest of the IT staff in how to diagnose incidents and problems, but also to accompany their application. It will not be effective only because the performers possess sufficient technical knowledge and skills in ITSM processes.

There are many techniques and methodologies that can be used, and your task is to try to evaluate the whole variety of different approaches. Part will simply not be applicable for your environment, but the more diverse approaches you know, the more likely you will be able to choose the best one when needed.