Golden rule git rebase

- Transfer

Hello!

We redid our web development course a bit and added another month to learn JS. Well, and as usual with us - consider something interesting that understands our course. In this case, git rebase.

Go.

What actually happens during git rebase, and why you should care.

The basics of rebase

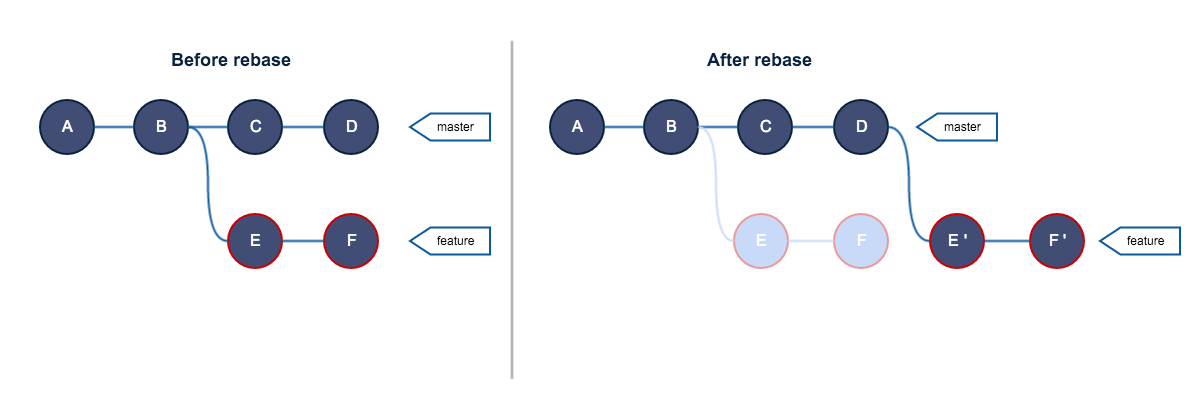

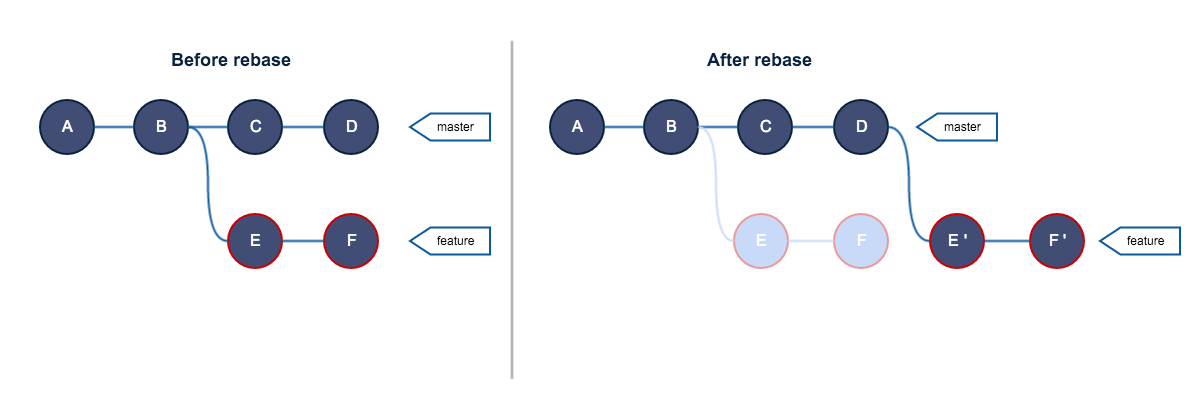

So you could imagine rebase in git:

You might think that when you rebase, you will “disconnect” the branch you want to rebase and “attach” it to the end of the other branch. This is not very far from the truth, but it is worth digging a little deeper. Here is what the rebase documentation says:

“Git-rebase: Forward-port local commits to the updated upstream head” - git documentation

Not very useful, is it? An example translation (and translation translation) could be:

git-rebase: Reapply all commits from your branch to the end of another branch.

The most important word here is “reapply,” because rebase is not just ctrl-x / ctrl-v from one branch to another. Rebase will consistently take all the commits from the branch you are in and reapply them to another branch. This has two important consequences:

Thus, this may be a more accurate idea of what actually happens during rebase:

As you can see, the feature branch has completely new commits. As already mentioned, it has the same set of changes, but completely different objects in terms of git. And you can also see that previous commits are not destroyed. They are simply not available directly. If you remember, a branch is just a pointer to commits. Therefore, if neither branches nor tags indicate commits, it becomes almost impossible to get them, but commits still exist.

Now let's talk about the famous golden rule.

The golden rebase rule is

“Do not rebase a common branch” - Everything about rebase

You have probably already come across this rule, perhaps formulated differently. For those who are not lucky, this rule is quite simple. Never, NEVER, NEVER rebase a shared branch. By common branch I mean a branch that exists in a remote repository and which other people from your team can fool themselves.

Too often, this rule is presented as divine truth, and I think you should understand it if you want to improve your understanding of git.

To do this, let's imagine a situation where a developer violates this rule and see what happens.

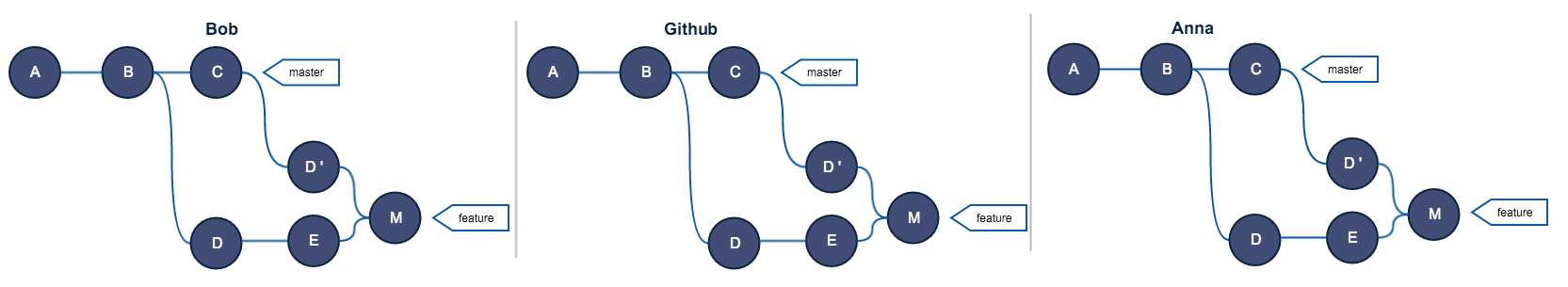

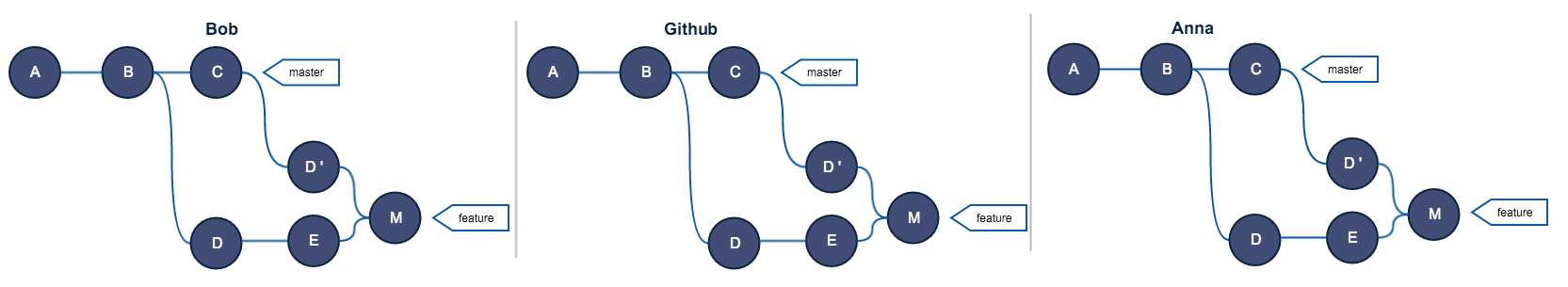

Let's say Bob and Anna are working on the same project. Here is the repository of Bob, Anna, and the remote repository on GitHub:

Everyone is in sync with the remote repository (GitHub)

Now Bob innocently breaks the golden rebase rule, at the same time Anna decides to work on this feature and creates a new commit:

Guess what will happen?

Bob tries to start, he gets a refusal and sees this message:

Oh My Zsh with the theme agnoster for those who are interested.

Git is not happy because he does not know how to merge the feature Bob branch with the feature GitHub branch. Usually, when you push your branch to a remote repository, git merges the branch you are trying to push with the branch located in the remote repository. To be precise, git is trying to rewind (fast-forward) your branch, and we will talk about this in a future post. What you need to remember is that the remote repository cannot, in a simple way, handle the relocated branch that Bob is trying to push.

One solution for Bob would be to make git push-force, which tells the remote repository:

“Don’t try to merge or do whatever work between what I push and what you already have. Erase your version of the feature branch, what I push is now the new feature branch ”

And this is what we end up with:

“Do not try to combine or do any other work between what I push and what you already have. Erase your version of the feature branch: what I push is now the new feature branch. ”

And this is what we get:

If Anna knew what was going to happen, she would not go to work this morning.

Now Anna wants to push her changes:

This is normal, git simply told Anna that she does not have a synchronized version of the feature branch, i.e. its version of the branch and the version of the GitHub branch are different. Naturally, Anna bullets. Just like git tries to merge your local branch with what is in the remote repository when pushing, git tries to combine what is in the remote repository with what is in your local branch when you pull.

This is how commits in the remote and local feature look in front of the pool:

When you bullet, git has to do a merge to resolve this problem. And here's what happens:

Commit M is a merge commit - a commit in which the Anna and GitHub branches finally reunited. Anna, finally, sighs with relief, she managed to resolve all the merger conflicts, and now she can start up her work. Bob decides to fire, and now everything is in sync.

One glance at this mess should be enough to convince you of the fairness of the golden rule. You should keep in mind that you are facing a mess created by only one person in a branch shared by only two people. Imagine doing this with a team of 10 people. One of the many reasons people use git is that you can easily “go back in time,” but the more messy your story is, the harder it gets.

You can also notice duplicate commits in the repository - D and D ', which have the same set of changes. The number of duplicate commits can be as large as the number of commits inside your rebased branch.

If you're still not sure, try introducing Emma, the third developer. She worked on feature before Bob ruined everything, and now wants to push the changes. Please note that she pushes after our previous mini-script.

hell bob!

update: As one reddit user noted, this post may make you think that rebase can only be used to rebase a branch to the top of another branch. This is not so, you can re-base the same branch, but that's another story.

Thanks for attention.

THE END

As always, we are waiting for your questions, comments here or on you can torment teachers in an open lesson.

We redid our web development course a bit and added another month to learn JS. Well, and as usual with us - consider something interesting that understands our course. In this case, git rebase.

Go.

What actually happens during git rebase, and why you should care.

The basics of rebase

So you could imagine rebase in git:

You might think that when you rebase, you will “disconnect” the branch you want to rebase and “attach” it to the end of the other branch. This is not very far from the truth, but it is worth digging a little deeper. Here is what the rebase documentation says:

“Git-rebase: Forward-port local commits to the updated upstream head” - git documentation

Not very useful, is it? An example translation (and translation translation) could be:

git-rebase: Reapply all commits from your branch to the end of another branch.

The most important word here is “reapply,” because rebase is not just ctrl-x / ctrl-v from one branch to another. Rebase will consistently take all the commits from the branch you are in and reapply them to another branch. This has two important consequences:

- By re-applying commits, git creates new ones. These new commits, even if they make the same set of changes, will be considered by git as completely different and independent.

- Git rebase reapplies commits without destroying old ones. This means that even after rebase, the old commits will still be in the / objects folder in your .git directory. If you're still unfamiliar with how git views and saves commits, there are a few interesting things you can learn.

Thus, this may be a more accurate idea of what actually happens during rebase:

As you can see, the feature branch has completely new commits. As already mentioned, it has the same set of changes, but completely different objects in terms of git. And you can also see that previous commits are not destroyed. They are simply not available directly. If you remember, a branch is just a pointer to commits. Therefore, if neither branches nor tags indicate commits, it becomes almost impossible to get them, but commits still exist.

Now let's talk about the famous golden rule.

The golden rebase rule is

“Do not rebase a common branch” - Everything about rebase

You have probably already come across this rule, perhaps formulated differently. For those who are not lucky, this rule is quite simple. Never, NEVER, NEVER rebase a shared branch. By common branch I mean a branch that exists in a remote repository and which other people from your team can fool themselves.

Too often, this rule is presented as divine truth, and I think you should understand it if you want to improve your understanding of git.

To do this, let's imagine a situation where a developer violates this rule and see what happens.

Let's say Bob and Anna are working on the same project. Here is the repository of Bob, Anna, and the remote repository on GitHub:

Everyone is in sync with the remote repository (GitHub)

Now Bob innocently breaks the golden rebase rule, at the same time Anna decides to work on this feature and creates a new commit:

Guess what will happen?

Bob tries to start, he gets a refusal and sees this message:

Oh My Zsh with the theme agnoster for those who are interested.

Git is not happy because he does not know how to merge the feature Bob branch with the feature GitHub branch. Usually, when you push your branch to a remote repository, git merges the branch you are trying to push with the branch located in the remote repository. To be precise, git is trying to rewind (fast-forward) your branch, and we will talk about this in a future post. What you need to remember is that the remote repository cannot, in a simple way, handle the relocated branch that Bob is trying to push.

One solution for Bob would be to make git push-force, which tells the remote repository:

“Don’t try to merge or do whatever work between what I push and what you already have. Erase your version of the feature branch, what I push is now the new feature branch ”

And this is what we end up with:

“Do not try to combine or do any other work between what I push and what you already have. Erase your version of the feature branch: what I push is now the new feature branch. ”

And this is what we get:

If Anna knew what was going to happen, she would not go to work this morning.

Now Anna wants to push her changes:

This is normal, git simply told Anna that she does not have a synchronized version of the feature branch, i.e. its version of the branch and the version of the GitHub branch are different. Naturally, Anna bullets. Just like git tries to merge your local branch with what is in the remote repository when pushing, git tries to combine what is in the remote repository with what is in your local branch when you pull.

This is how commits in the remote and local feature look in front of the pool:

A--B--C--D' origin/feature // GitHub

A--B--D--E feature // AnnaWhen you bullet, git has to do a merge to resolve this problem. And here's what happens:

Commit M is a merge commit - a commit in which the Anna and GitHub branches finally reunited. Anna, finally, sighs with relief, she managed to resolve all the merger conflicts, and now she can start up her work. Bob decides to fire, and now everything is in sync.

One glance at this mess should be enough to convince you of the fairness of the golden rule. You should keep in mind that you are facing a mess created by only one person in a branch shared by only two people. Imagine doing this with a team of 10 people. One of the many reasons people use git is that you can easily “go back in time,” but the more messy your story is, the harder it gets.

You can also notice duplicate commits in the repository - D and D ', which have the same set of changes. The number of duplicate commits can be as large as the number of commits inside your rebased branch.

If you're still not sure, try introducing Emma, the third developer. She worked on feature before Bob ruined everything, and now wants to push the changes. Please note that she pushes after our previous mini-script.

hell bob!

update: As one reddit user noted, this post may make you think that rebase can only be used to rebase a branch to the top of another branch. This is not so, you can re-base the same branch, but that's another story.

Thanks for attention.

THE END

As always, we are waiting for your questions, comments here or on you can torment teachers in an open lesson.