Antiquities: Minidisk in its natural habitat

Unlike cassettes, which were absolutely all, and CDs, MDs have not become a generally accepted, universal, ubiquitous format. You can find a lot of reasons why it happened, starting with technical difficulties in the early nineties and ending with the policy and issues of copyright protection. But the main reason: it was expensive. In the entire history of the existence of this audio format, I have never even considered it seriously, choosing first cassettes, then CDs. In the middle of the two thousandth, money appeared, but the meaning disappeared, the minidisk incredibly quickly lost all relevance as a digital medium, losing to players and smartphones without moving parts.

But I always wanted to. These small discs in multi-colored plastic cases, CD aesthetics and floppy disks in one bottle, are incredibly cool and feature-rich compact writing players. It was the format of the future that never arrived. Minidisk is a combination of complex technologies that, alas, appeared too late to make the format truly popular. Minidisk is also a story about the persistence of a Japanese company that continued to develop the ecosystem in spite of everything for two decades. And now it is a collector's delight: the devices and the discs themselves are still quite accessible, but they already have a sufficient degree of vintage. In general, we must take: for the last month I became the owner of two mini-disk decks, seven portable devices, and now I know almost everything about mini-disks. Is this a cool format? Of course. Was there any practical sense in it? This question is more difficult to answer, but let's try.

I keep the diary of the collector of old pieces of iron in real time in the Telegram . About some features of mini-disk devices there are written in more detail, in particular - about measurements and blind testing .

The minidisk as a format, as well as the first device for playback and recording, was introduced in late 1992. In 2013, Sony announced the end of the production of players: at that time it was clear that the end had come not only to the MD, but to all optical media in general, at least in the context of mass use. Twenty-one years of the format can be divided into two epochs that are seriously different from each other - before the iPod and after. Today I will talk about MDs in a natural, pre-Internet habitat, and in order to correctly assess the value of this format from 2019, let's move on to the atmosphere of the early nineties. Setting up the environment: there is no Internet, MP3 is only finalized as standard and almost unknown to anyone. The coolest processor is the 486th at 50 megahertz, but the 286th will do, The main user operating system is MS-DOS, Windows 3.x graphics mode is used strictly as needed. There are two main music carriers: CDs (buy music from the store) and tapes (also buy or record yourself).

Minidisk was developed as a replacement cassette. The idea was this: let's make a digital audio media that can be rewritten many times, repeat the success of portable cassette players, only with the obvious advantages of digital sound. In the late eighties, when the format was developed, it was a very difficult task. The CD-R standard was finalized in 1988, but until 1996, only very wealthy people could “record music on discs”. Recording equipment resembled a refrigerator and cost tens of thousands of dollars. Sony, the developer of the format, originally planned to continue cooperation with Philips, but the negotiations were deadlocked. A Dutch electronics manufacturer wanted to make digital format cheap using tape. Sony insisted on something like an incredibly successful CD. In some negotiations ended and promising digital formats to replace the audio cassette was two. More precisely, three: there was still the standard Digital Audio Tape, using the technologies used in video recorders.

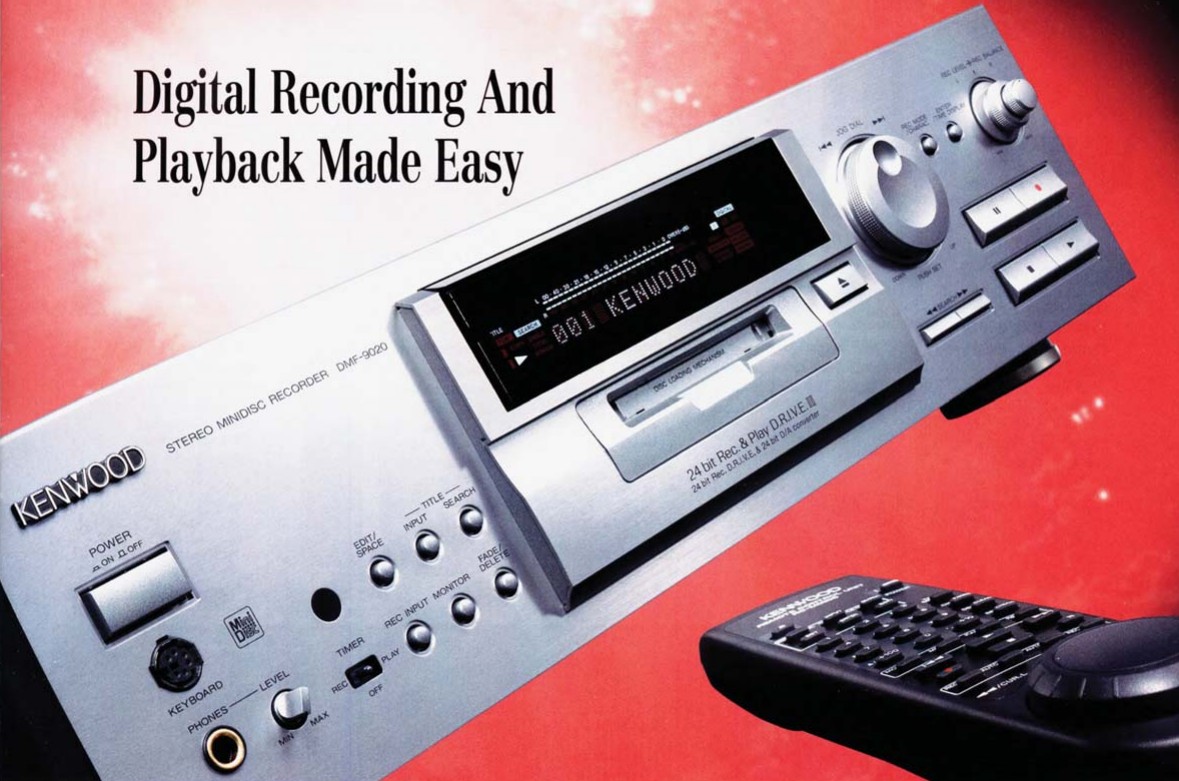

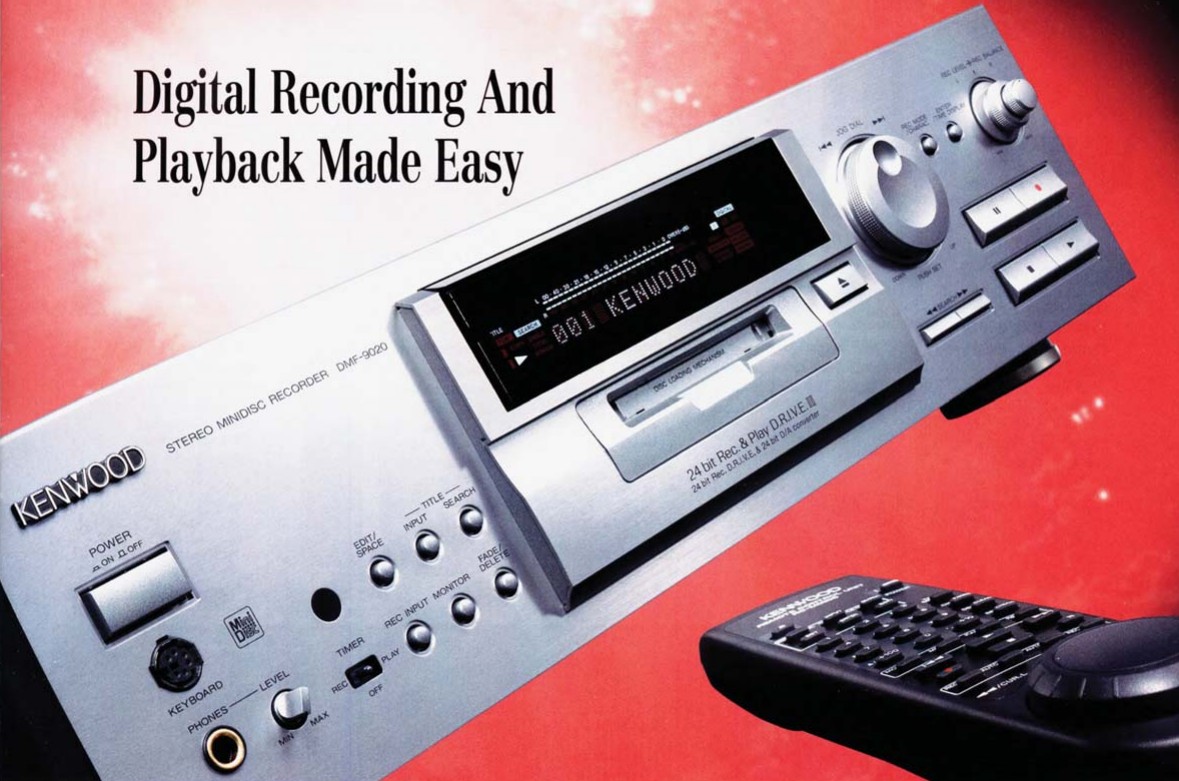

In early December, I decide to purchase my first minidisc device. The choice is both big and not so much. I spend hours looking at the technology database on the incredibly useful site minidisc.org : it was created in 1995, was last updated in 2011, and is itself a museum piece. As usual, really cool devices from the past are expensive, copies of life-beaten copies with incomprehensible performance sell for cheap. I make the first deal about a non-portable, but a stationary device: Kenwood DMF-9020 mini-disk deck . This is the coolest Kenwood model of 1999, according to its characteristics it is not inferior to very expensive (and then, and now) Sony models of the “elite series”. Included with it, they give me 10 pieces of minidisc beaten with life, enough for a start.

I bring the deck home, and, naturally, I try to insert a minidisk into it like a floppy disk, with a protective shutter in front. It is necessary to insert so that the curtain looks to the right. For some reason, all the disks are defined as clean, and after a couple of hours of work with a screwdriver, I understand that the deck is broken. More precisely not so, it works, if you put it vertically: a clear sign of problems with the mechanism responsible for ensuring that the laser shines where necessary. In order not to use the deck in such a strange position, I unscrew and put upright the drive itself for reading minidisks.

If you already had to disassemble, you can see how it works. Reading data from the MD does not differ much from that of a CD. But the recording is made using a magnetic head: if necessary, it “falls” onto the disk from above, coming into direct contact with the magnetic layer. The laser is also used during recording: its power increases about 10 times, and it heats the disk surface to a temperature corresponding to the Curie point - about 200 degrees. At this temperature, it becomes possible to overwrite information on the magnetic layer. Data reading is possible using a laser head, due to the Faraday effect , in which differently magnetized areas of the disk have different polarization.

Why didn't they use the laser for recording too? In the late eighties, CD technology existed, but was prohibitively expensive, and without the possibility of rewriting. Magneto-optical media in computer technology are generally the forerunners of CDs; at the time of development, this technology was cheaper and allowed devices to be made compact. Wait, what about the Digital Audio Tape? This format, although it allows you to store more data on the media, requires a complex tape drive mechanism, which is incredibly difficult to implement in a portable device. In the entire history of DAT, asingle portable player has been released , and if you find it now, most likely it will not work - too unreliable . Amendment: the player was not the only one; examples of DAT player models are given in this.comments, thanks twelve .

Minidisk was created with an eye on portable use and was supposed to replace the portable cassette players popular in the eighties and nineties. Therefore, the size of the disk is almost two times smaller than that of the CD (64 mm vs. 120). The disk itself is placed in a cartridge with a protective shutter, and outside the device is fully protected from external influence. Small size led to a smaller capacity compared to CD. At the same time, it was necessary to ensure a sound duration comparable to CD - 74 minutes - which means that you need to apply lossy audio data compression.

Although Sony had the ability to use standardized digital audio compression algorithms (Philips took this path), the Japanese company developed its own format - Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding or ATRAC. In its original version, this is a format with a fixed bit rate of 292 kilobits per second or a little more than two megabytes per minute of sound. Compared with the original CD bitrate (1411 kilobits per second), the compression is about five times.

It looks good on paper, but in fact the very first device for recording and playing mini discs turned out to be very controversial. This is a Sony MZ-1 player that went on sale in November 1992. First, it was huge, weighed about 700 grams and definitely did not fit in a pocket. Secondly, the charge of a proprietary nickel-cadmium battery was enough for 60 minutes of recording or 75 minutes of playback. Thirdly, it cost incredibly expensive: 750 dollars (1350 modern, taking into account inflation). Finally, the 74-minute minidisks did not work out at first, only the 60-minute ones were available, and they cost more than $ 15 apiece. Not surprisingly, with the exception of Japan, the first entry of the MD to the market was a failure.

Why did this happen? There are many reasons, and you can start with the difficulties in creating a truly compact (and economical) mechanism for reading and writing MDDs. There was also the problem of computing power, which can be fully appreciated thanks to this excellent post about 32-bit Intel processors. Two years before the release of MD, the coolest desktop processor was the Intel 486 with a frequency of 20 MHz. In the test, by reference, he encodes the five-minute track into ogg format for three hours ! Of course, this is slightly unfair:

Ogg Vorbis is a modern lossy compression format designed for other computational powers. Nevertheless, the complexity of the task that Sony engineers faced can be imagined: they needed to provide audio compression with real-time losses in a portable device, when even large computers did not cope with this task very well.

In addition to all other troubles, the very first version of the ATRAC codec has serious problems with sound quality: eyewitnesses call clearly audible artifacts the "sound of champagne" for the characteristic crackle in the high frequency range. Lossy audio compression involves decomposing the signal into frequencies and amplitudes, and the smaller the individual slices, the better, and the more computing power is required. The rougher the analysis of the original signal, the more information you have to throw out in the process, the higher the distortion. Hence the high-frequency crash.

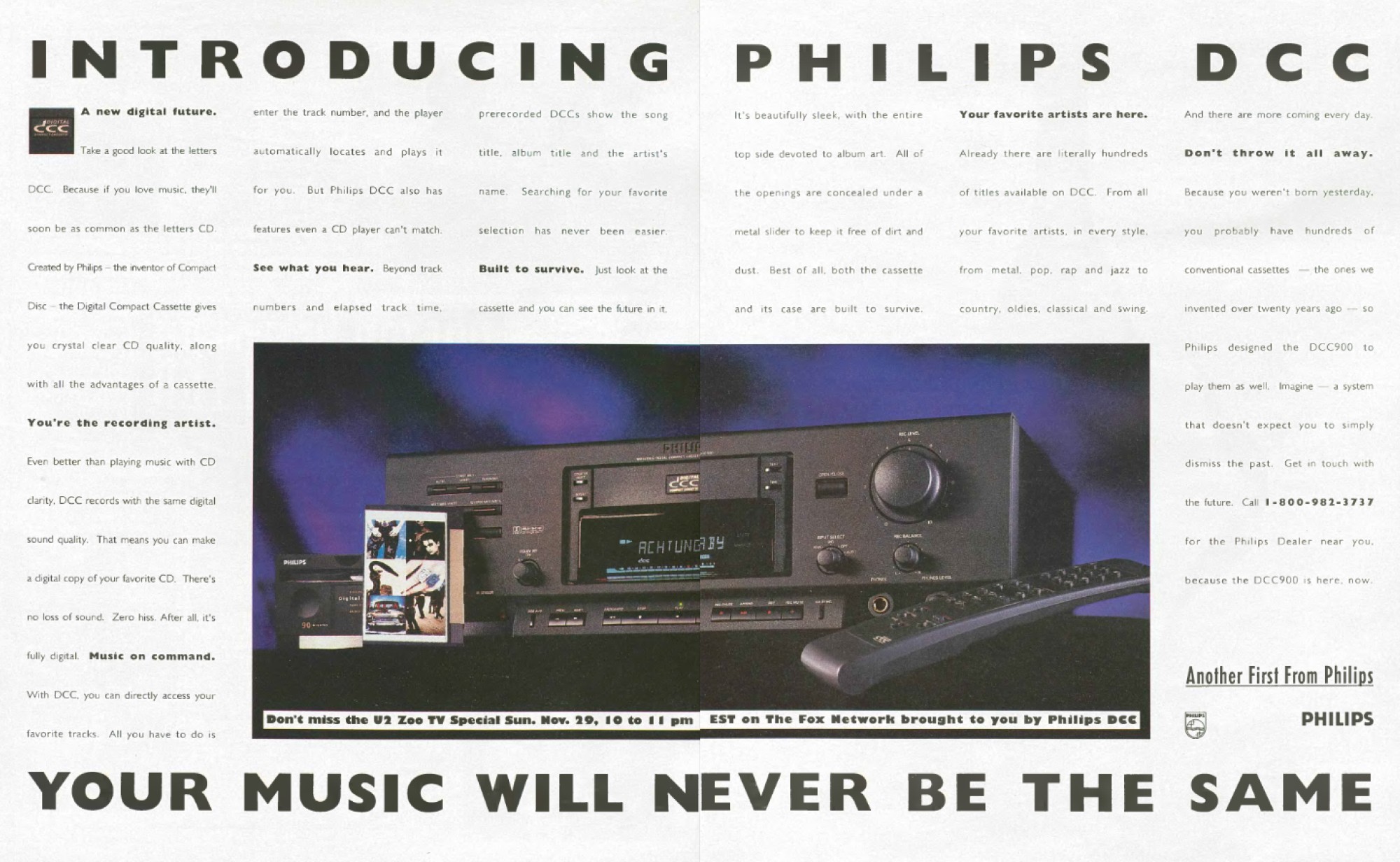

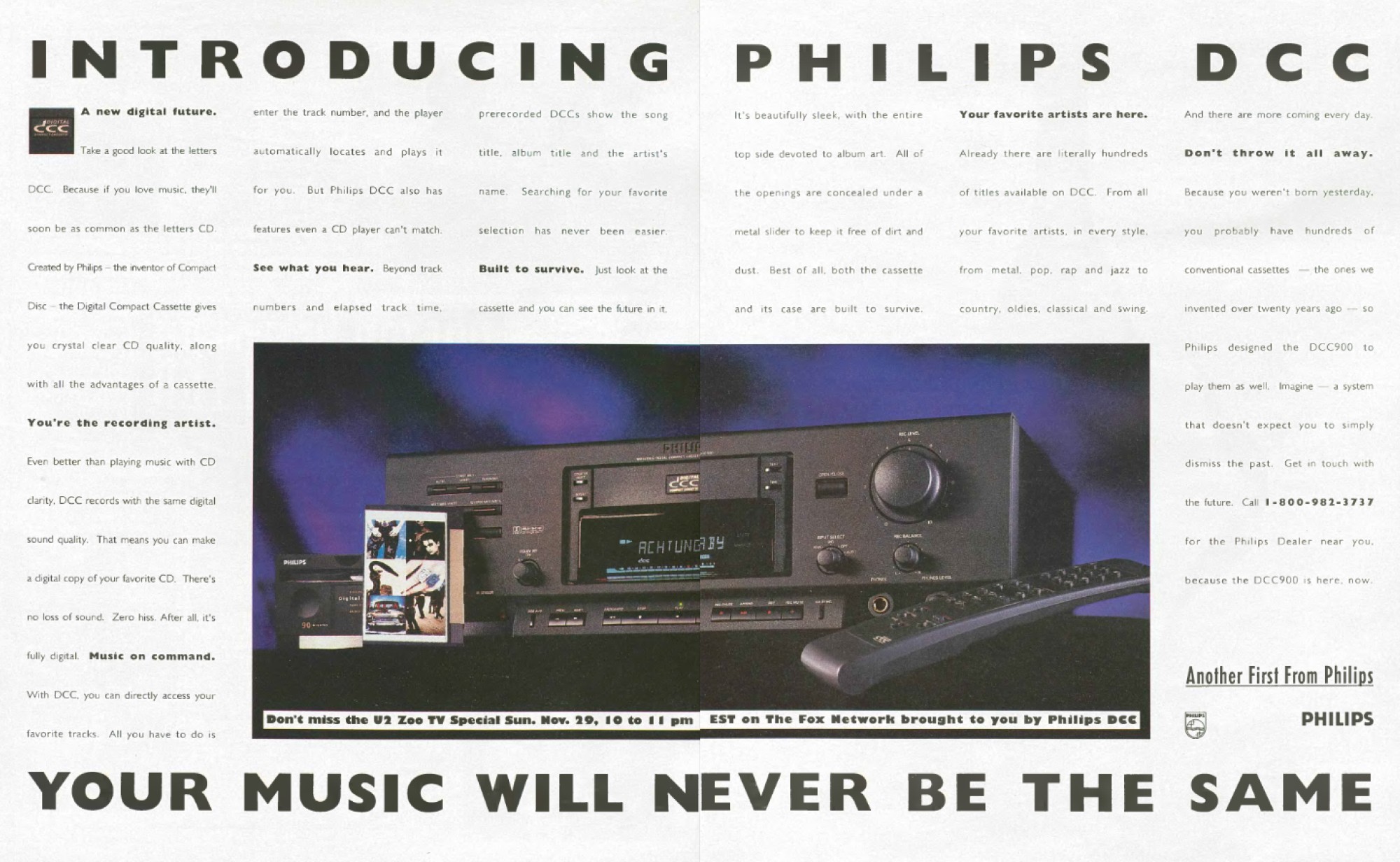

Oh yeah, forget about the competition. Philips finished its “cassette” digital format and presented it almost simultaneously with the mini disc. Digital Compact Cassette used a slightly modified mechanism of a conventional tape recorder, due to which the media were cheaper - they were essentially regular tapes in a new package and with modified tape chemistry. Compression based on MPEG-1 with slightly better characteristics than ATRAC was used - a bitrate of 384 kilobits per second, up to 90 minutes of music was placed on the tape. With this format, too, everything was not perfect: at the time of launch, it was possible to develop stationary devices, but not portable ones. Unlike MDs, digital cassettes did not have random access to tracks, and “rewinding the tape” was perceived as something old-school and unfashionable, whether you were at least a hundred times digital.

The first MD recorder, however, showed two major advantages of the format. This is a 10-second data buffering, due to which the playback was not interrupted while walking or running. In portable CD players from 1993 to 1997, the standard would be “anti-shock” for three seconds - memory chips are still expensive, and a CD buffer is needed more spaciously. The second advantage: the ability to arbitrarily edit the recording on the disk, swap and delete tracks, record new ones, divide the tracks into parts. Finally, you could enter and save titles for individual tracks and the entire disc.

From 1993 to 1996, Sony consistently doped portable devices, each year releasing a pair of recording device and a clean player. Players, thanks to a simpler design, become moderately compact already in 1994. In 1996, even the recorder is almost as big as cassette devices. So far, the oldest device in my collection is the Sony MZ-R30 still working on a tricky battery (already Li-Ion), but it is already able to last eight hours in playback mode and five in recording mode: quite decent for the mid-nineties. The recorder is still expensive, about $ 550 at the beginning of sales. Minidisks can be bought for about $ 8-10 for the 74-minute version and $ 7 for the 60-minute one.

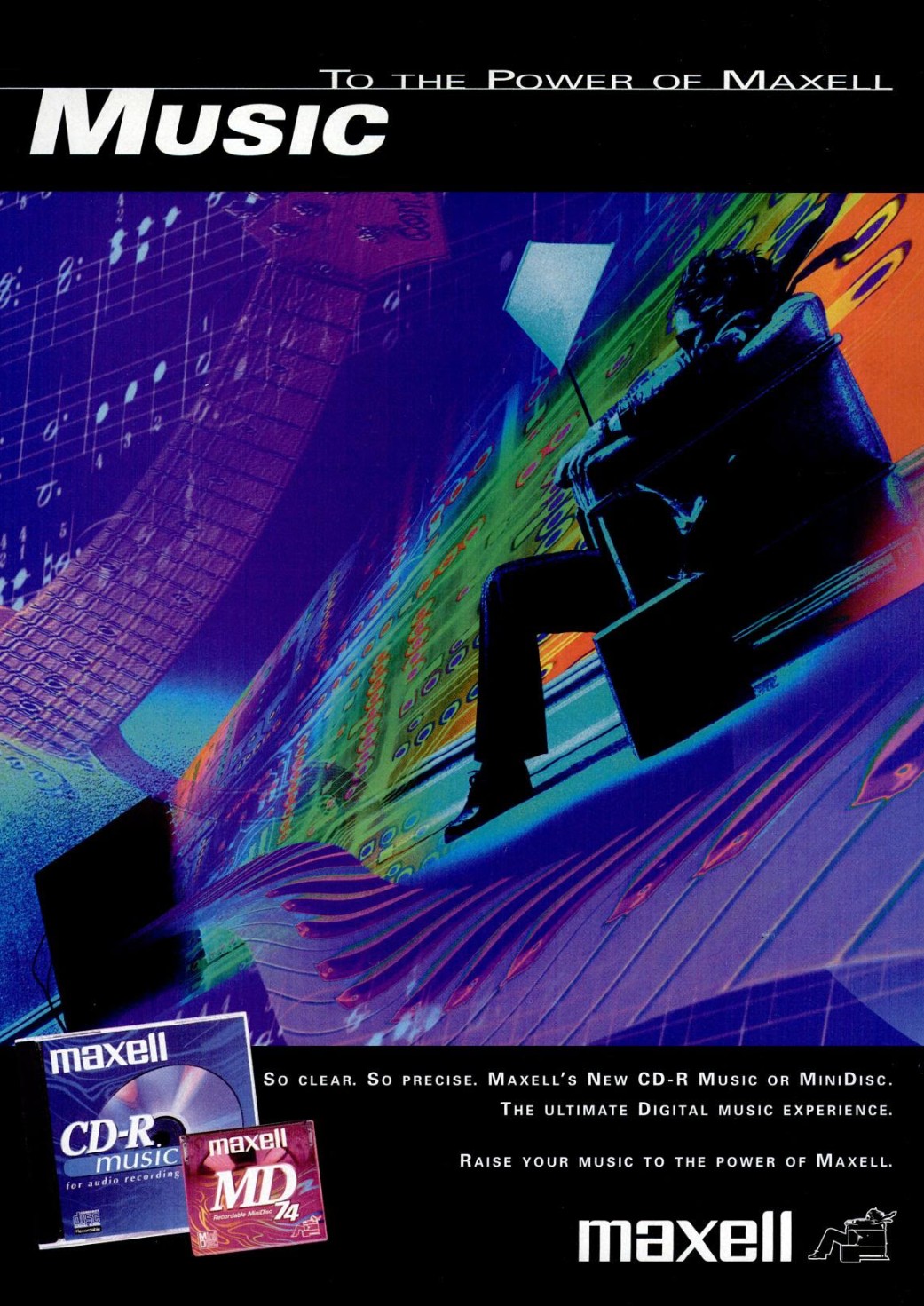

The cost of devices is not conducive to the spread of minidisks among young people - the main consumers of portable equipment. They are trying to reorient the format to an adult consumer with money: home decks and car stereos are produced, kits from stationary and portable devices are sold at a discount to write discs at home and listen on the go.

What is it like to record minidisks? The advantage of the format is that it is digital, and since the very first device all recorders are equipped with a digital optical input. My Kenwood deck is also equipped with a coaxial digital interface, which I connect to an external sound card. Further simple: turn on the playback on the computer, turn on the recording on the MD recorder. Beginning in 1997, recorders are able to start recording automatically at the start of data transmission in digital. The recorder independently divides the recording into tracks, by pauses between them, and if there is a compatible CD player and by exact markers of the original recording.

In modern conditions, recording on optical media in a real-time mode looks rather strange, because even a CD-R disc can be cut in a couple of minutes. After the recording, I edit: according to the information from the computer I divide the soundtrack into tracks in the right places. Almost all the decks are equipped with an encoder - it allows you to accurately select the starting point for a new song, and then it is used to enter track names. If two tracks were divided erroneously, you can connect them back to one, the main thing is not to confuse the sequence - by default, the current track is connected to the next, and not the previous one. All changes are written to the memory of the recorder, and upon completion the disk must be removed from the device. When you click the Eject button, all entered information is recorded in the TOC section - an analogue of the file allocation table on a hard disk or diskette.

How does this sound? In 1996, the fourth version of the ATRAC format was released, and many sources claim that it is very difficult or almost impossible to distinguish it from the sound of the original uncompressed CD. My deck supports ATRAC version 4.5 and processes audio in 24-bit format. With objective measurements in the RightMark Audio Analyzer program, the Kenwood device shows the parameters even “slightly better than CDs”.

But wait, how much better is a CD if we have a bitrate five times less? ATRAC, like other lossy audio compression algorithms, uses the characteristics of human hearing: the sensitivity of our ears changes depending on the frequency of the sound, and in certain cases we will hear only one of the two tones of different frequencies.

This is what the spectrogram of original music looks like and after compression in ATRAC format. The high frequencies that we hear the worst of all suffer the most. But if there is only high-frequency content in the phonogram, as it happens during measurements (a sinusoidal signal is reproduced at a certain frequency), the compression algorithm will direct all forces there, and the audio information will be saved. Music is not a test sound, and the complexity of the compression process is to throw out the unnecessary and save what we are sure to hear. There are examples of complex sound fragments in which a compression algorithm breaks down and generates a well-audible noise.

How to evaluate it for your own ears and reproducing equipment? The perception of sound is an extremely subjective thing, and in general you need to have a very well-trained ear, it is good to know the theory in order to hear the problems where they are. It is difficult for me, as a non-professional, to do this, but it is easy to persuade myself that I can hear the difference when there really isn’t. Only blind testing can help you figure it out: a comparison of two pieces of music in a situation where you don’t know if this is the original or a compressed copy. I record the same piece from a well-known album, in its original form, and with compression in ATRAC, and use the ABX Comparator pluginfor comparison. 16 times I make a decision which of the two musical fragments is recorded with digital compression, and which without. 9 times I make the right choice, 7 times I am mistaken - it turns out that with high probability I just try to guess. My ears and my (quite good) technique do not allow me to hear the difference between a MD and a CD.

In 1998, Sony is launching a new offensive on the digital music market. In the United States alone, $ 30 million is invested in advertising and special promotions, a huge sum for the consumer electronics market. New models of players are being developed and produced, partners are catching up - the devices are also manufactured by Sharp, Panasonic, Kenwood and other mainly Japanese companies. Minidisc pop stars are promoted, and cameo movies are being organized through Sony's entertainment division. Probably the most famous "role" of the minidisk takes place in the first part of the "Matrix" trilogy.

But this is 1999, and in 1998, Sony played almost the main role in the clip for Freestyler’s Finnish Bomfunk MC’s composition.

To control the reality in the clip, the remote control from the Sony MZ-R55 player is used and I just could not get past this exhibit.

The player came to me in almost perfect condition, in a box, but with corrosion in the battery compartment, this is where the discount came from. This is the first Sony player, the dimensions of which are not much larger than the actual media. The power supply has been redone by 1.5 volts, a (rather short-lived) flat battery like gumstick is used. With him, the player works only 4 hours in playback mode. Not much. You can fasten an external container to it on two finger-type batteries and increase the operating time to 16 hours, but then the device’s dimensions will be almost equal to the MZ-R30 model from 1996.

The control panel is a super fashionable piece of portable technology from the mid-nineties to the mid-two thousandth: with it you can never get the device out of your pocket. It is very convenient, and starting with the model MZ-R55, the track name and other information is also displayed on the remote.

In 1998, I study at an American school and for the first time I see a minidisk with classmates. They give me a listen, it looks and sounds amazing. Nevertheless, having saved money, I still buy another cassette player. Why? Firstly, there is little money: I spend $ 80, and the cheapest MD recorder costs 250. Secondly, well, I will buy a recorder. We need wheels, and at that time they cost 5-7 dollars apiece. Of course, with a mini-disc device, you can have only one disc, and record new music on it at least every evening. But this is inconvenient, and I have about fifty cassettes at that time, and you can always buy a new album in the store: I spend pocket money on Prodigy and the soundtrack for that very Matrix. Branded albums are also sold on minidisks too, but there are relatively few of them - Sony has never been able to sign anyone on the format, apart from Sony's own label and satellites. They are expensive - $ 15 - as a CD, and cassettes are cheaper. Net cassettes cost less than a dollar for a 90-minute tape. As a result, even though I like the technology, I don’t even consider buying a mini-disc player.

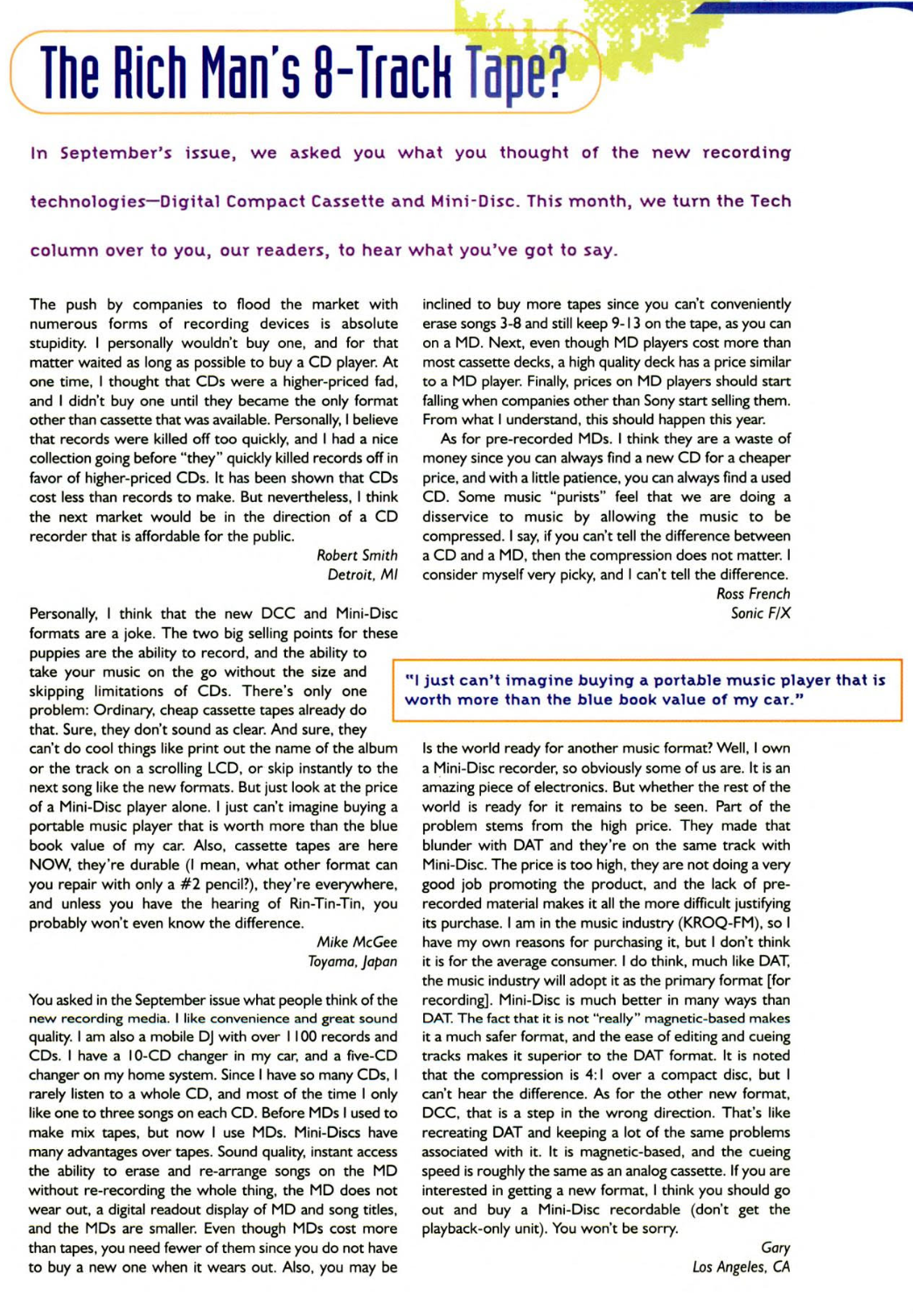

In 1995, the music magazine CMJ New Music Monthly conducted a survey of readers about the format of mini discs. The answers are very characteristic. Youth reports that there is no money. Professionals are positive: it is an inexpensive digital recorder for field work. Older consumers at the time are already a bit tired of the leapfrog of music formats. Imagine: if in 1995 you were thirty, then you still caught Daddy's bobby with ribbons. A schoolboy was buying singles on records, and maybe was 8-Track. Then the tape. Then the CD - it took about 10 years for this format to become really popular. And just 10 years after the CD, does Sony release another type of digital format? Yes, how much can you! The media often criticizes Sony for the wrong marketing policy: it could not explain to the consumer that the minidisk is not a CD replacement, but an addition.

In 1998, the minidisk is clearly advertised as a replacement for an audio cassette. It is assumed that you have a collection of music on a CD, and on the minidisc you make collections, rewrite the albums for listening in the car and on the go, so as not to scratch expensive originals. Damn, if I had a mini-disk device, a CD, and music in 1998, I would certainly enjoy using it all. But I only had tapes. If I considered the digital format at that moment, I would rather choose a portable CD player, but even for me it was unnecessarily expensive. Perhaps I would choose the Philips Digital Compact Cassette format - it provides backward compatibility with conventional cassettes, they can be listened to on new devices (but not recorded). But I could not do it:

The advertisement worked: in 1998 in the USA as many players were sold as in the previous five years of the format. In pieces, this is about a million devices - a bit. CD burners for computers in the same year sold more than five million. The format is well received in Japan, but the situation is different there. First, the population has relatively high incomes and a lot of free money - housing is expensive, cars, too, there is more money left for everyday purchases. Secondly, the price of a CD is historically higher than American and European almost doubled, but the business of rental music on CDs is flourishing. I took a new album in the evening, rewrote, returned it in the morning, and listen - beauty!

The culture of using minidisc devices not according to the instructions basically solved two problems: how more convenient to enter track names, and how to circumvent copy protection. Serial Copy Management System ( SCMS) - the result of a legal battle around the first conditionally home digital recording format - Digital Audio Tape. The American recording industry took the technology of digital copying music from CDs into bayonets, threatened lawsuits, and in 1992 sponsored a law imposing a tax on digital recordable media and obligating manufacturers to restrict copying of digital phonograms. The principle of protection in MD technology is simple: a digital copy of any source can be made only once. Rewrite the CD by number - you can. It’s impossible to make a digital copy of this MD, when you try to record, the device will simply refuse to work. Without restrictions, you can make copies through an analog connection, with a slight loss in quality.

In 2019, this restriction does not bother me at all, but if we restore the experience twenty years ago, it will be entirely. The easiest way to use for the digital rewriting of protected content is the interface that the SCMS flags simply ignore, and the professional technique that existed at that time allowed it. In some models, SCMS could be circumvented due to manufacturer errors. For example, in the Sony MZ-R50 recorder of the early series, the protection system was simply turned off in the service menu. I do not have such a player, so my choice is an operation known as TOC Cloning.

Cloning a record on the contents of the MDD exploits the fact that this TOC is updated last. Let's make a digital recording on the MD, which can then be rewritten to another MD, without any restrictions. To do this, I take a clean minidisk and on my Kenwood deck I record a few minutes of silence over it via analogentrance. I save the changes, now it is recorded in the TOC that there is one track on this disc, which, according to the SCMS logic, can be copied without any problems. Now I erase the information on the disc, and overwrite another track, this time through the digital input. And then the magic happens: after recording, but before updating the information in the TOC, I turn off the device. If you turn it back on, the recorder will remember that it has unsaved changes, but I reset the device settings with a key combination. As a result, the TOC table remains old, there is still information about the unprotected track, but the record is digital instead!

Manipulations with TOC also made it possible to record a bit more music than allowed on 60 and 74-minute discs, in some cases they helped to restore information from a dead MD, or roll back erroneous changes. Not all devices support this operation. The ability to enter track names is supported by absolutely all MD recorders, but not all allow you to do so conveniently. To improve convenience, a variety of methods were used, not counting the standard ones (for example, a serial interface and proprietary computer software for very expensive home Sony recorders). Pocket computers with an infrared port or infrared adapters for a computer were used: they made it possible to enter information about tracks in advance, and then quickly transfer it to the device, emulating keystrokes on the remote. For portable players that support character input from a wired remote, did special adapters. If there were no other options, complex PC-controlled constructions were built, quickly pressing the buttons of the portable recorder in the desired sequence.

In my case, everything is much simpler: the Kenwood deck is one of the few equipped with a PS / 2 port for a conventional computer keyboard. In total, up to 1785 characters can be recorded for one minidisk: if there are a lot of tracks, you will have a choice - several tracks with long names or all with short ones. After recording a disc and dividing it into tracks, I plug in the keyboard, enter text input mode, drive in titles for the entire disc, and for individual tracks. In some recorders, you can also automatically or manually enter the date and time of the recording, which is useful when using the device as a voice recorder. Impressions of connecting the keyboard to a non-computer device are, of course, strange, but you can arrange a minidisk on the highest level. There is little use for the titles - the screens of portable players are small, but at least you should keep the disc name,

For 1998, the minidisk looks like a quite good and promising format. The devices are compact, the recording quality is excellent, the discs are getting cheaper and by the end of the millennium they are already selling for 3-5 dollars. And that sales are small - so this is nothing, CDs won only 9-10 years after launch, they were able to overcome audio cassettes in terms of sales. Recordable CDs pose a certain threat: as early as 1996, the cost of drives drops to $ 1,000, and carriers to $ 10. Sony expected that such prices would last for several more years, but in 1997 a rewritable CD-RW format appeared, and prices for regular discs by 1999 would fall to a half dollars. But this is not even the main thing. In 1997 this is also happening:

The world's first MP3 player, the South Korean MPMan F10, is of course not a competitor to the minidisc. It costs 600 dollars and for this money you get 64 megabytes of memory, enough for an hour of music with a bitrate of 128 kilobits per second. But it was the future, which, for the present imperceptibly, but sent a minidisk to the past. In 1997, I first became acquainted with the MP3 format, and was very impressed with the ability to store music directly on your hard drive, and not just play it from a CD. There is a culture of "music on the computer", which will be stimulated by piracy: in 1999, the file-sharing network Napster began to work.

Sony is not that completely ignoring the miniDisc computer potential. In 1995, Sony's external MDH-10 SCSI drive came out ( hereit has a good video review). The MD-Data format allows you to store up to 140 megabytes on one minidisk. A year earlier, Iomega released magnetic disks and Zip drives with a capacity of 100 megabytes. It seems that minidisc has an advantage, but Sony behaved in the traditional Sony-style here. A computer drive could only play music from ordinary mini discs. He couldn’t record music, he couldn’t even record data - for MDH-10, his own separate format was invented, incompatible with the existing one. User studies have shown that music and data mini-disks are almost the same, and why this slingshot was put on the path of progress is not clear. Apparently in order to sell MD-Data discs with a premium.

The idea did not take off: the next attempt to adapt the minidisk for files will be made only in 2004. In the late nineties, Sony developed 650 MB MD-Data disks, but they are completely incompatible with conventional MDs. And this idea also failed. But it would seem that this was the potential: back in 1992, Sony could replace the MiniDisc floppy disk and cover the competing Iomega Zip and LS-120 formats with a copper basin. But this is such a backstage mind: in the early nineties there was not even a web, and it was not easy to imagine what popularity the Internet in general and computers in particular would gain by the end of the decade. Even if Bill Gates managed to ignore the Internet in the release of Windows 95, then what about the initially non-computer company Sony.

In 1998, Xitel launched the MDPort device - in fact, it is a simple external sound card with a USB connector on one end and an optical digital (later also analog) output on the other. Sony is aware of the popularity of the device and begins to trade sets of mini-disk recorder and "computer" adapter. Now you can burn your MP3s to minidisk! Yes, but it's still a half decision. The ideal option would be the presence of a slot for a mini-disk in every computer and laptop and direct recording of music, data, without intermediaries. But for this, the format should be a little more open than the proprietary MD and ATRAC.

And what is the result? First, you convert one lossy compression format to another, and in the late nineties you probably only have a bunch of badly encoded MP3s with bitrates (at best!) 128 kilobits per second. Many sound cards of those times, if they had a digital output, usually worked at a sampling rate of 48 kilohertz. That is, there was also a double conversion - 44 kilohertz of the source code were converted to 48, received on the MD recorder, and there they were converted back to 44 kHz native format. Nothing good came of it, and the main thing was still the cassette approach: I inserted the media, connected the wiring, pressed the record and waited. The future is when you transfer music to where you want to, in the form in which it is preserved.

In 1999, Sony could buy the cheapest Sony recorder for $ 200, for example, the MZ-R37. It is not as fashionable as the MZ-R55, and it has a remote without a display, but it works on two 15-hour finger-type batteries, has an iron case and a full set of connectors. Although the minidisk was too expensive for the average consumer all its life, the format was actively used by professionals who needed a portable and sufficiently high-quality tool for recording and playing sound. Minususes for pop artists, recording bird songs for scientists, creatingnasal translations of films in post-Soviet Russia - for all this minidisc was actively used, and for a long time there was no alternative to it (in terms of recording quality and autonomy).

Even in 2019, I like the minidisk in its original form. I haven’t been able to repair Kenwood's deco yet, even replacing the laser module helped for a short while - I’m waiting for the new mechanism to be delivered. In the meantime, he reads disks well, but writes with errors, and I use the deck to convert the digital signal from electrical to optical, write the discs to a portable device, then insert the disc back into the deck to enter letters. And recently, simply because I can, I connected a smartphone and a portable recorder with wires, and recorded a disc right from Google Play Music. At the same time, I appreciated the advantage of minidisks over streaming services - the old technology can switch between tracks without pauses, but the new one does not.

Of course, the charm of modernity is that nothing needs to be written down: take it and listen, at least from the phone, at least from the computer. But in the context of the pre-Internet era, the minidisk is quite good, and it certainly has its own unique style, with a buzzing mechanism, elegant design of both carriers and players. My favorite device is a fairly simple Sony MZ-E20 player, with convenient buttons and a relatively powerful headphone amplifier (15 milliwatts per channel versus the standard five). Will minidisk be my favorite outdated music format? Well no. Cassettes heartier .

In the twenty-first century, Sony will three times try to adapt the format to the MP3 era, and will be defeated three times. The devices of the new century are also interesting in their own way, but I have more frustration from them than pleasure. About minidisc with the ability to directly connect to a computer, I will tell in the second episode of this miniseries on January 7. Stay in touch!

But I always wanted to. These small discs in multi-colored plastic cases, CD aesthetics and floppy disks in one bottle, are incredibly cool and feature-rich compact writing players. It was the format of the future that never arrived. Minidisk is a combination of complex technologies that, alas, appeared too late to make the format truly popular. Minidisk is also a story about the persistence of a Japanese company that continued to develop the ecosystem in spite of everything for two decades. And now it is a collector's delight: the devices and the discs themselves are still quite accessible, but they already have a sufficient degree of vintage. In general, we must take: for the last month I became the owner of two mini-disk decks, seven portable devices, and now I know almost everything about mini-disks. Is this a cool format? Of course. Was there any practical sense in it? This question is more difficult to answer, but let's try.

I keep the diary of the collector of old pieces of iron in real time in the Telegram . About some features of mini-disk devices there are written in more detail, in particular - about measurements and blind testing .

The minidisk as a format, as well as the first device for playback and recording, was introduced in late 1992. In 2013, Sony announced the end of the production of players: at that time it was clear that the end had come not only to the MD, but to all optical media in general, at least in the context of mass use. Twenty-one years of the format can be divided into two epochs that are seriously different from each other - before the iPod and after. Today I will talk about MDs in a natural, pre-Internet habitat, and in order to correctly assess the value of this format from 2019, let's move on to the atmosphere of the early nineties. Setting up the environment: there is no Internet, MP3 is only finalized as standard and almost unknown to anyone. The coolest processor is the 486th at 50 megahertz, but the 286th will do, The main user operating system is MS-DOS, Windows 3.x graphics mode is used strictly as needed. There are two main music carriers: CDs (buy music from the store) and tapes (also buy or record yourself).

Minidisk was developed as a replacement cassette. The idea was this: let's make a digital audio media that can be rewritten many times, repeat the success of portable cassette players, only with the obvious advantages of digital sound. In the late eighties, when the format was developed, it was a very difficult task. The CD-R standard was finalized in 1988, but until 1996, only very wealthy people could “record music on discs”. Recording equipment resembled a refrigerator and cost tens of thousands of dollars. Sony, the developer of the format, originally planned to continue cooperation with Philips, but the negotiations were deadlocked. A Dutch electronics manufacturer wanted to make digital format cheap using tape. Sony insisted on something like an incredibly successful CD. In some negotiations ended and promising digital formats to replace the audio cassette was two. More precisely, three: there was still the standard Digital Audio Tape, using the technologies used in video recorders.

The first approach to the projectile

In early December, I decide to purchase my first minidisc device. The choice is both big and not so much. I spend hours looking at the technology database on the incredibly useful site minidisc.org : it was created in 1995, was last updated in 2011, and is itself a museum piece. As usual, really cool devices from the past are expensive, copies of life-beaten copies with incomprehensible performance sell for cheap. I make the first deal about a non-portable, but a stationary device: Kenwood DMF-9020 mini-disk deck . This is the coolest Kenwood model of 1999, according to its characteristics it is not inferior to very expensive (and then, and now) Sony models of the “elite series”. Included with it, they give me 10 pieces of minidisc beaten with life, enough for a start.

I bring the deck home, and, naturally, I try to insert a minidisk into it like a floppy disk, with a protective shutter in front. It is necessary to insert so that the curtain looks to the right. For some reason, all the disks are defined as clean, and after a couple of hours of work with a screwdriver, I understand that the deck is broken. More precisely not so, it works, if you put it vertically: a clear sign of problems with the mechanism responsible for ensuring that the laser shines where necessary. In order not to use the deck in such a strange position, I unscrew and put upright the drive itself for reading minidisks.

If you already had to disassemble, you can see how it works. Reading data from the MD does not differ much from that of a CD. But the recording is made using a magnetic head: if necessary, it “falls” onto the disk from above, coming into direct contact with the magnetic layer. The laser is also used during recording: its power increases about 10 times, and it heats the disk surface to a temperature corresponding to the Curie point - about 200 degrees. At this temperature, it becomes possible to overwrite information on the magnetic layer. Data reading is possible using a laser head, due to the Faraday effect , in which differently magnetized areas of the disk have different polarization.

Why didn't they use the laser for recording too? In the late eighties, CD technology existed, but was prohibitively expensive, and without the possibility of rewriting. Magneto-optical media in computer technology are generally the forerunners of CDs; at the time of development, this technology was cheaper and allowed devices to be made compact. Wait, what about the Digital Audio Tape? This format, although it allows you to store more data on the media, requires a complex tape drive mechanism, which is incredibly difficult to implement in a portable device. In the entire history of DAT, a

epic fail

Minidisk was created with an eye on portable use and was supposed to replace the portable cassette players popular in the eighties and nineties. Therefore, the size of the disk is almost two times smaller than that of the CD (64 mm vs. 120). The disk itself is placed in a cartridge with a protective shutter, and outside the device is fully protected from external influence. Small size led to a smaller capacity compared to CD. At the same time, it was necessary to ensure a sound duration comparable to CD - 74 minutes - which means that you need to apply lossy audio data compression.

Although Sony had the ability to use standardized digital audio compression algorithms (Philips took this path), the Japanese company developed its own format - Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding or ATRAC. In its original version, this is a format with a fixed bit rate of 292 kilobits per second or a little more than two megabytes per minute of sound. Compared with the original CD bitrate (1411 kilobits per second), the compression is about five times.

It looks good on paper, but in fact the very first device for recording and playing mini discs turned out to be very controversial. This is a Sony MZ-1 player that went on sale in November 1992. First, it was huge, weighed about 700 grams and definitely did not fit in a pocket. Secondly, the charge of a proprietary nickel-cadmium battery was enough for 60 minutes of recording or 75 minutes of playback. Thirdly, it cost incredibly expensive: 750 dollars (1350 modern, taking into account inflation). Finally, the 74-minute minidisks did not work out at first, only the 60-minute ones were available, and they cost more than $ 15 apiece. Not surprisingly, with the exception of Japan, the first entry of the MD to the market was a failure.

Why did this happen? There are many reasons, and you can start with the difficulties in creating a truly compact (and economical) mechanism for reading and writing MDDs. There was also the problem of computing power, which can be fully appreciated thanks to this excellent post about 32-bit Intel processors. Two years before the release of MD, the coolest desktop processor was the Intel 486 with a frequency of 20 MHz. In the test, by reference, he encodes the five-minute track into ogg format for three hours ! Of course, this is slightly unfair:

Ogg Vorbis is a modern lossy compression format designed for other computational powers. Nevertheless, the complexity of the task that Sony engineers faced can be imagined: they needed to provide audio compression with real-time losses in a portable device, when even large computers did not cope with this task very well.

In addition to all other troubles, the very first version of the ATRAC codec has serious problems with sound quality: eyewitnesses call clearly audible artifacts the "sound of champagne" for the characteristic crackle in the high frequency range. Lossy audio compression involves decomposing the signal into frequencies and amplitudes, and the smaller the individual slices, the better, and the more computing power is required. The rougher the analysis of the original signal, the more information you have to throw out in the process, the higher the distortion. Hence the high-frequency crash.

Oh yeah, forget about the competition. Philips finished its “cassette” digital format and presented it almost simultaneously with the mini disc. Digital Compact Cassette used a slightly modified mechanism of a conventional tape recorder, due to which the media were cheaper - they were essentially regular tapes in a new package and with modified tape chemistry. Compression based on MPEG-1 with slightly better characteristics than ATRAC was used - a bitrate of 384 kilobits per second, up to 90 minutes of music was placed on the tape. With this format, too, everything was not perfect: at the time of launch, it was possible to develop stationary devices, but not portable ones. Unlike MDs, digital cassettes did not have random access to tracks, and “rewinding the tape” was perceived as something old-school and unfashionable, whether you were at least a hundred times digital.

The second approach to the projectile

The first MD recorder, however, showed two major advantages of the format. This is a 10-second data buffering, due to which the playback was not interrupted while walking or running. In portable CD players from 1993 to 1997, the standard would be “anti-shock” for three seconds - memory chips are still expensive, and a CD buffer is needed more spaciously. The second advantage: the ability to arbitrarily edit the recording on the disk, swap and delete tracks, record new ones, divide the tracks into parts. Finally, you could enter and save titles for individual tracks and the entire disc.

From 1993 to 1996, Sony consistently doped portable devices, each year releasing a pair of recording device and a clean player. Players, thanks to a simpler design, become moderately compact already in 1994. In 1996, even the recorder is almost as big as cassette devices. So far, the oldest device in my collection is the Sony MZ-R30 still working on a tricky battery (already Li-Ion), but it is already able to last eight hours in playback mode and five in recording mode: quite decent for the mid-nineties. The recorder is still expensive, about $ 550 at the beginning of sales. Minidisks can be bought for about $ 8-10 for the 74-minute version and $ 7 for the 60-minute one.

The cost of devices is not conducive to the spread of minidisks among young people - the main consumers of portable equipment. They are trying to reorient the format to an adult consumer with money: home decks and car stereos are produced, kits from stationary and portable devices are sold at a discount to write discs at home and listen on the go.

What is it like to record minidisks? The advantage of the format is that it is digital, and since the very first device all recorders are equipped with a digital optical input. My Kenwood deck is also equipped with a coaxial digital interface, which I connect to an external sound card. Further simple: turn on the playback on the computer, turn on the recording on the MD recorder. Beginning in 1997, recorders are able to start recording automatically at the start of data transmission in digital. The recorder independently divides the recording into tracks, by pauses between them, and if there is a compatible CD player and by exact markers of the original recording.

In modern conditions, recording on optical media in a real-time mode looks rather strange, because even a CD-R disc can be cut in a couple of minutes. After the recording, I edit: according to the information from the computer I divide the soundtrack into tracks in the right places. Almost all the decks are equipped with an encoder - it allows you to accurately select the starting point for a new song, and then it is used to enter track names. If two tracks were divided erroneously, you can connect them back to one, the main thing is not to confuse the sequence - by default, the current track is connected to the next, and not the previous one. All changes are written to the memory of the recorder, and upon completion the disk must be removed from the device. When you click the Eject button, all entered information is recorded in the TOC section - an analogue of the file allocation table on a hard disk or diskette.

Blind testing

How does this sound? In 1996, the fourth version of the ATRAC format was released, and many sources claim that it is very difficult or almost impossible to distinguish it from the sound of the original uncompressed CD. My deck supports ATRAC version 4.5 and processes audio in 24-bit format. With objective measurements in the RightMark Audio Analyzer program, the Kenwood device shows the parameters even “slightly better than CDs”.

But wait, how much better is a CD if we have a bitrate five times less? ATRAC, like other lossy audio compression algorithms, uses the characteristics of human hearing: the sensitivity of our ears changes depending on the frequency of the sound, and in certain cases we will hear only one of the two tones of different frequencies.

This is what the spectrogram of original music looks like and after compression in ATRAC format. The high frequencies that we hear the worst of all suffer the most. But if there is only high-frequency content in the phonogram, as it happens during measurements (a sinusoidal signal is reproduced at a certain frequency), the compression algorithm will direct all forces there, and the audio information will be saved. Music is not a test sound, and the complexity of the compression process is to throw out the unnecessary and save what we are sure to hear. There are examples of complex sound fragments in which a compression algorithm breaks down and generates a well-audible noise.

How to evaluate it for your own ears and reproducing equipment? The perception of sound is an extremely subjective thing, and in general you need to have a very well-trained ear, it is good to know the theory in order to hear the problems where they are. It is difficult for me, as a non-professional, to do this, but it is easy to persuade myself that I can hear the difference when there really isn’t. Only blind testing can help you figure it out: a comparison of two pieces of music in a situation where you don’t know if this is the original or a compressed copy. I record the same piece from a well-known album, in its original form, and with compression in ATRAC, and use the ABX Comparator pluginfor comparison. 16 times I make a decision which of the two musical fragments is recorded with digital compression, and which without. 9 times I make the right choice, 7 times I am mistaken - it turns out that with high probability I just try to guess. My ears and my (quite good) technique do not allow me to hear the difference between a MD and a CD.

Jack

In 1998, Sony is launching a new offensive on the digital music market. In the United States alone, $ 30 million is invested in advertising and special promotions, a huge sum for the consumer electronics market. New models of players are being developed and produced, partners are catching up - the devices are also manufactured by Sharp, Panasonic, Kenwood and other mainly Japanese companies. Minidisc pop stars are promoted, and cameo movies are being organized through Sony's entertainment division. Probably the most famous "role" of the minidisk takes place in the first part of the "Matrix" trilogy.

But this is 1999, and in 1998, Sony played almost the main role in the clip for Freestyler’s Finnish Bomfunk MC’s composition.

To control the reality in the clip, the remote control from the Sony MZ-R55 player is used and I just could not get past this exhibit.

The player came to me in almost perfect condition, in a box, but with corrosion in the battery compartment, this is where the discount came from. This is the first Sony player, the dimensions of which are not much larger than the actual media. The power supply has been redone by 1.5 volts, a (rather short-lived) flat battery like gumstick is used. With him, the player works only 4 hours in playback mode. Not much. You can fasten an external container to it on two finger-type batteries and increase the operating time to 16 hours, but then the device’s dimensions will be almost equal to the MZ-R30 model from 1996.

The control panel is a super fashionable piece of portable technology from the mid-nineties to the mid-two thousandth: with it you can never get the device out of your pocket. It is very convenient, and starting with the model MZ-R55, the track name and other information is also displayed on the remote.

In 1998, I study at an American school and for the first time I see a minidisk with classmates. They give me a listen, it looks and sounds amazing. Nevertheless, having saved money, I still buy another cassette player. Why? Firstly, there is little money: I spend $ 80, and the cheapest MD recorder costs 250. Secondly, well, I will buy a recorder. We need wheels, and at that time they cost 5-7 dollars apiece. Of course, with a mini-disc device, you can have only one disc, and record new music on it at least every evening. But this is inconvenient, and I have about fifty cassettes at that time, and you can always buy a new album in the store: I spend pocket money on Prodigy and the soundtrack for that very Matrix. Branded albums are also sold on minidisks too, but there are relatively few of them - Sony has never been able to sign anyone on the format, apart from Sony's own label and satellites. They are expensive - $ 15 - as a CD, and cassettes are cheaper. Net cassettes cost less than a dollar for a 90-minute tape. As a result, even though I like the technology, I don’t even consider buying a mini-disc player.

In 1995, the music magazine CMJ New Music Monthly conducted a survey of readers about the format of mini discs. The answers are very characteristic. Youth reports that there is no money. Professionals are positive: it is an inexpensive digital recorder for field work. Older consumers at the time are already a bit tired of the leapfrog of music formats. Imagine: if in 1995 you were thirty, then you still caught Daddy's bobby with ribbons. A schoolboy was buying singles on records, and maybe was 8-Track. Then the tape. Then the CD - it took about 10 years for this format to become really popular. And just 10 years after the CD, does Sony release another type of digital format? Yes, how much can you! The media often criticizes Sony for the wrong marketing policy: it could not explain to the consumer that the minidisk is not a CD replacement, but an addition.

In 1998, the minidisk is clearly advertised as a replacement for an audio cassette. It is assumed that you have a collection of music on a CD, and on the minidisc you make collections, rewrite the albums for listening in the car and on the go, so as not to scratch expensive originals. Damn, if I had a mini-disk device, a CD, and music in 1998, I would certainly enjoy using it all. But I only had tapes. If I considered the digital format at that moment, I would rather choose a portable CD player, but even for me it was unnecessarily expensive. Perhaps I would choose the Philips Digital Compact Cassette format - it provides backward compatibility with conventional cassettes, they can be listened to on new devices (but not recorded). But I could not do it:

The advertisement worked: in 1998 in the USA as many players were sold as in the previous five years of the format. In pieces, this is about a million devices - a bit. CD burners for computers in the same year sold more than five million. The format is well received in Japan, but the situation is different there. First, the population has relatively high incomes and a lot of free money - housing is expensive, cars, too, there is more money left for everyday purchases. Secondly, the price of a CD is historically higher than American and European almost doubled, but the business of rental music on CDs is flourishing. I took a new album in the evening, rewrote, returned it in the morning, and listen - beauty!

Dirty hacks

The culture of using minidisc devices not according to the instructions basically solved two problems: how more convenient to enter track names, and how to circumvent copy protection. Serial Copy Management System ( SCMS) - the result of a legal battle around the first conditionally home digital recording format - Digital Audio Tape. The American recording industry took the technology of digital copying music from CDs into bayonets, threatened lawsuits, and in 1992 sponsored a law imposing a tax on digital recordable media and obligating manufacturers to restrict copying of digital phonograms. The principle of protection in MD technology is simple: a digital copy of any source can be made only once. Rewrite the CD by number - you can. It’s impossible to make a digital copy of this MD, when you try to record, the device will simply refuse to work. Without restrictions, you can make copies through an analog connection, with a slight loss in quality.

In 2019, this restriction does not bother me at all, but if we restore the experience twenty years ago, it will be entirely. The easiest way to use for the digital rewriting of protected content is the interface that the SCMS flags simply ignore, and the professional technique that existed at that time allowed it. In some models, SCMS could be circumvented due to manufacturer errors. For example, in the Sony MZ-R50 recorder of the early series, the protection system was simply turned off in the service menu. I do not have such a player, so my choice is an operation known as TOC Cloning.

Cloning a record on the contents of the MDD exploits the fact that this TOC is updated last. Let's make a digital recording on the MD, which can then be rewritten to another MD, without any restrictions. To do this, I take a clean minidisk and on my Kenwood deck I record a few minutes of silence over it via analogentrance. I save the changes, now it is recorded in the TOC that there is one track on this disc, which, according to the SCMS logic, can be copied without any problems. Now I erase the information on the disc, and overwrite another track, this time through the digital input. And then the magic happens: after recording, but before updating the information in the TOC, I turn off the device. If you turn it back on, the recorder will remember that it has unsaved changes, but I reset the device settings with a key combination. As a result, the TOC table remains old, there is still information about the unprotected track, but the record is digital instead!

Manipulations with TOC also made it possible to record a bit more music than allowed on 60 and 74-minute discs, in some cases they helped to restore information from a dead MD, or roll back erroneous changes. Not all devices support this operation. The ability to enter track names is supported by absolutely all MD recorders, but not all allow you to do so conveniently. To improve convenience, a variety of methods were used, not counting the standard ones (for example, a serial interface and proprietary computer software for very expensive home Sony recorders). Pocket computers with an infrared port or infrared adapters for a computer were used: they made it possible to enter information about tracks in advance, and then quickly transfer it to the device, emulating keystrokes on the remote. For portable players that support character input from a wired remote, did special adapters. If there were no other options, complex PC-controlled constructions were built, quickly pressing the buttons of the portable recorder in the desired sequence.

In my case, everything is much simpler: the Kenwood deck is one of the few equipped with a PS / 2 port for a conventional computer keyboard. In total, up to 1785 characters can be recorded for one minidisk: if there are a lot of tracks, you will have a choice - several tracks with long names or all with short ones. After recording a disc and dividing it into tracks, I plug in the keyboard, enter text input mode, drive in titles for the entire disc, and for individual tracks. In some recorders, you can also automatically or manually enter the date and time of the recording, which is useful when using the device as a voice recorder. Impressions of connecting the keyboard to a non-computer device are, of course, strange, but you can arrange a minidisk on the highest level. There is little use for the titles - the screens of portable players are small, but at least you should keep the disc name,

Internet is coming

For 1998, the minidisk looks like a quite good and promising format. The devices are compact, the recording quality is excellent, the discs are getting cheaper and by the end of the millennium they are already selling for 3-5 dollars. And that sales are small - so this is nothing, CDs won only 9-10 years after launch, they were able to overcome audio cassettes in terms of sales. Recordable CDs pose a certain threat: as early as 1996, the cost of drives drops to $ 1,000, and carriers to $ 10. Sony expected that such prices would last for several more years, but in 1997 a rewritable CD-RW format appeared, and prices for regular discs by 1999 would fall to a half dollars. But this is not even the main thing. In 1997 this is also happening:

The world's first MP3 player, the South Korean MPMan F10, is of course not a competitor to the minidisc. It costs 600 dollars and for this money you get 64 megabytes of memory, enough for an hour of music with a bitrate of 128 kilobits per second. But it was the future, which, for the present imperceptibly, but sent a minidisk to the past. In 1997, I first became acquainted with the MP3 format, and was very impressed with the ability to store music directly on your hard drive, and not just play it from a CD. There is a culture of "music on the computer", which will be stimulated by piracy: in 1999, the file-sharing network Napster began to work.

Sony is not that completely ignoring the miniDisc computer potential. In 1995, Sony's external MDH-10 SCSI drive came out ( hereit has a good video review). The MD-Data format allows you to store up to 140 megabytes on one minidisk. A year earlier, Iomega released magnetic disks and Zip drives with a capacity of 100 megabytes. It seems that minidisc has an advantage, but Sony behaved in the traditional Sony-style here. A computer drive could only play music from ordinary mini discs. He couldn’t record music, he couldn’t even record data - for MDH-10, his own separate format was invented, incompatible with the existing one. User studies have shown that music and data mini-disks are almost the same, and why this slingshot was put on the path of progress is not clear. Apparently in order to sell MD-Data discs with a premium.

The idea did not take off: the next attempt to adapt the minidisk for files will be made only in 2004. In the late nineties, Sony developed 650 MB MD-Data disks, but they are completely incompatible with conventional MDs. And this idea also failed. But it would seem that this was the potential: back in 1992, Sony could replace the MiniDisc floppy disk and cover the competing Iomega Zip and LS-120 formats with a copper basin. But this is such a backstage mind: in the early nineties there was not even a web, and it was not easy to imagine what popularity the Internet in general and computers in particular would gain by the end of the decade. Even if Bill Gates managed to ignore the Internet in the release of Windows 95, then what about the initially non-computer company Sony.

In 1998, Xitel launched the MDPort device - in fact, it is a simple external sound card with a USB connector on one end and an optical digital (later also analog) output on the other. Sony is aware of the popularity of the device and begins to trade sets of mini-disk recorder and "computer" adapter. Now you can burn your MP3s to minidisk! Yes, but it's still a half decision. The ideal option would be the presence of a slot for a mini-disk in every computer and laptop and direct recording of music, data, without intermediaries. But for this, the format should be a little more open than the proprietary MD and ATRAC.

And what is the result? First, you convert one lossy compression format to another, and in the late nineties you probably only have a bunch of badly encoded MP3s with bitrates (at best!) 128 kilobits per second. Many sound cards of those times, if they had a digital output, usually worked at a sampling rate of 48 kilohertz. That is, there was also a double conversion - 44 kilohertz of the source code were converted to 48, received on the MD recorder, and there they were converted back to 44 kHz native format. Nothing good came of it, and the main thing was still the cassette approach: I inserted the media, connected the wiring, pressed the record and waited. The future is when you transfer music to where you want to, in the form in which it is preserved.

Minidisk in natural habitat

In 1999, Sony could buy the cheapest Sony recorder for $ 200, for example, the MZ-R37. It is not as fashionable as the MZ-R55, and it has a remote without a display, but it works on two 15-hour finger-type batteries, has an iron case and a full set of connectors. Although the minidisk was too expensive for the average consumer all its life, the format was actively used by professionals who needed a portable and sufficiently high-quality tool for recording and playing sound. Minususes for pop artists, recording bird songs for scientists, creating

Even in 2019, I like the minidisk in its original form. I haven’t been able to repair Kenwood's deco yet, even replacing the laser module helped for a short while - I’m waiting for the new mechanism to be delivered. In the meantime, he reads disks well, but writes with errors, and I use the deck to convert the digital signal from electrical to optical, write the discs to a portable device, then insert the disc back into the deck to enter letters. And recently, simply because I can, I connected a smartphone and a portable recorder with wires, and recorded a disc right from Google Play Music. At the same time, I appreciated the advantage of minidisks over streaming services - the old technology can switch between tracks without pauses, but the new one does not.

Of course, the charm of modernity is that nothing needs to be written down: take it and listen, at least from the phone, at least from the computer. But in the context of the pre-Internet era, the minidisk is quite good, and it certainly has its own unique style, with a buzzing mechanism, elegant design of both carriers and players. My favorite device is a fairly simple Sony MZ-E20 player, with convenient buttons and a relatively powerful headphone amplifier (15 milliwatts per channel versus the standard five). Will minidisk be my favorite outdated music format? Well no. Cassettes heartier .

In the twenty-first century, Sony will three times try to adapt the format to the MP3 era, and will be defeated three times. The devices of the new century are also interesting in their own way, but I have more frustration from them than pleasure. About minidisc with the ability to directly connect to a computer, I will tell in the second episode of this miniseries on January 7. Stay in touch!