Three years of the lunar microsatellite project: stages of maturation

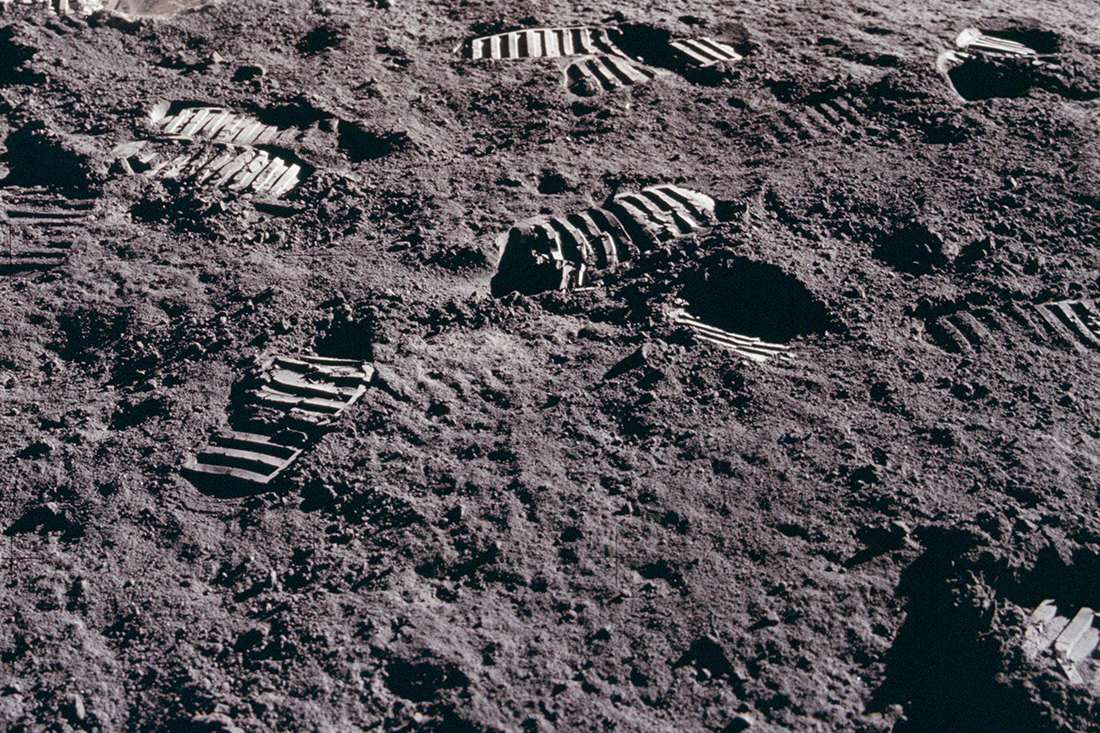

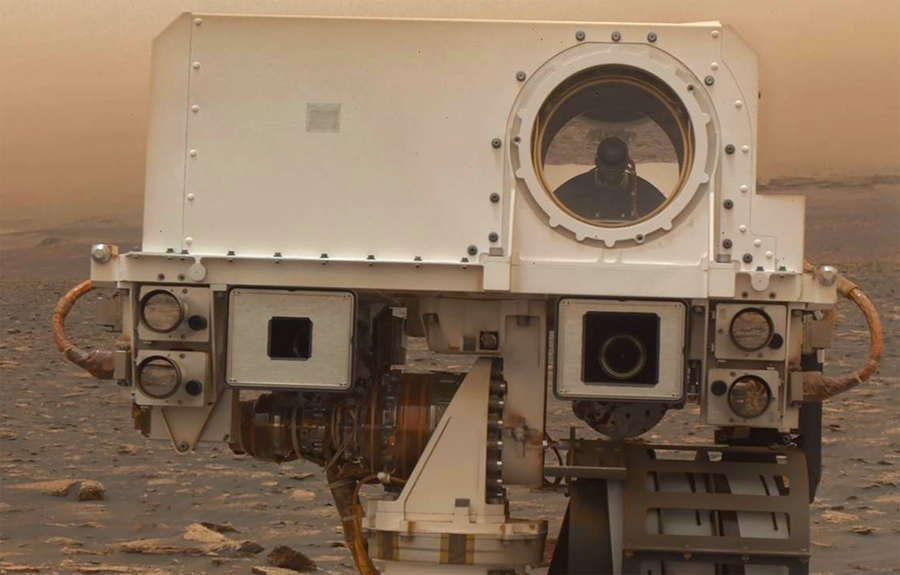

Three years ago I suggested developing a spacecraft to launch to the Moon and photograph the landing sites of the Apollo and Lunokhod with sufficient quality to distinguish traces left there half a century ago. A group of enthusiastic engineers volunteered to take part in the project and set about this task. The first stage of development - a technical description of the satellite (avanproekt) - required three years and has not yet been completed.

To perform the first stage, I announced a fundraising on the website boomstarter.ru . We were supported by one and a half thousand people, and the total amount collected amounted to 1 million 750 thousand rubles. In the project, all the work goes on a volunteer basis, part of the money raised went to the acquisition of equipment and components for the development of prototypes of a radio communication system and laser communication. We deferred the bulk of the sum to pay for the state expertise of the prepared project at the Roskosmos Institute. If after the examination the funds remain, we will divide them among the participants of the development, in proportion to the contribution to the common cause, that is, to the text of the final document.

Here are the answers to some frequent questions about the project.

The task for the team was not only to prepare a technical description of the project, but also to make it in accordance with the documentation requirements of the Russian space industry. Preparing such an advance project on a small spacecraft would have cost approximately one million rubles, and the specialized organizations would have done it for us in a couple of months, but we would not just give money to some design bureau, get the desired document and put it on the shelf. The goal was to form a group of specialists capable of both making an advance project, and assembling a photosatellite, and implementing the entire flight program.

Actually, this is partly the reason for the delay. Not all enthusiasts were ready to work in a team, not all are able to put the results of their work into a serious engineering document, and not everyone was able to combine volunteering with family / study / work. I see the main fault in the delays on myself - I did not show proper exactingness and perseverance, I was not inspired by personal example.

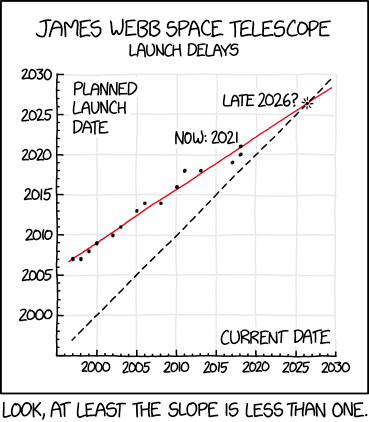

Today, work on the formation of the team continues, and the document is slowly but surely being prepared. It should be noted that non-compliance with the deadlines in the space industry is a common phenomenon.

You can talk about this in more detail using our own example.

What is the complexity of creating spacecraft? Why not just “buy and assemble a designer”? Why almost all space projects related to the development of new technology do not withstand the proposed dates? After all, all spacecraft have about one set of onboard systems, and space seems to be the same everywhere - vacuum, radiation, sunlight ... It seems strange that in space programs not everything is unified like that of personal computers, so that you can do it yourself at home or in garage to assemble your own satellite. But in reality, almost every spacecraft is handmade, twisted wires and scotch wires, a creative approach and often self-written software.

Only in some multi-satellite projects a pre-production level has been reached: GPS, GLONASS, geostationary telecommunication satellites, and some other projects.

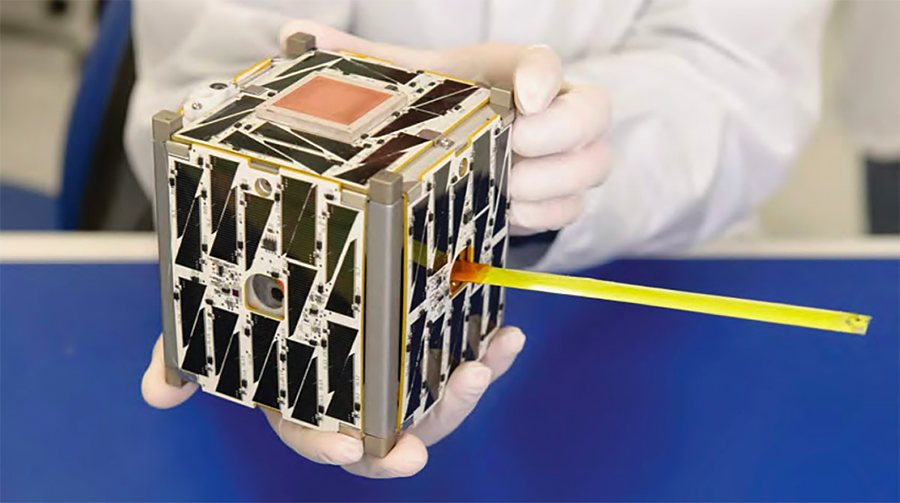

Nanosatellites of the CubeSat format are more or less unified due to their low cost, standard dimensions and popularity among institutes and private companies.

Why are satellites different everywhere?

When compared with personal computers, the first difference from astronautics is the size of the series. All operating spacecraft in near-earth orbits are about one and a half thousand. So many computers can be found in one urban neighborhood.

Second difference- the difference of physical conditions in different orbits. In low Earth orbit, about 40-45% of the time, satellites are in the shadow of the Earth. This means that they can simply get rid of the excess heat accumulated from the sun and from the heating of the onboard systems. The device in geostationary orbit or interplanetary flight is covered almost 100% of the time, and the heat release is a big problem - this complicates the system for ensuring the thermal regime, increases the size of radiators and mass. Therefore, it is impossible to simply take the design of the near-Earth satellite and launch it towards the Moon.

With a lunar satellite, thermal complexity doubles: first you have to fly in constant sunlight, and then spin around the moon, gradually decreasing. The lower - the longer the shadow area. And we haven’t gotten to thermal calculations yet, until we finish the description of the basic design and composition of the instruments.

In a low Earth orbit, satellites can use a magnetic field for orientation — changing their position in space relative to the center of mass (in other words, a satellite can choose where to “look” or turn around with solar batteries, using the same force that deflects the compass needle). That is, low-orbit near-earth satellites are not necessarily fuel and rocket engines — there are enough solar batteries to power flywheel engines and magnetic coils to work effectively and bring benefits. Where the magnetic field is weakened or absent altogether, the device needs rocket engines for making turns. If you simply take some near-earth satellite and launch to the Moon, it will turn into a useless squeaker and will only be able to send an endless "beep-beep-beep" in all directions, which is quickly lost in the radio noise of the cosmos. In the best case, it can be twisted along one axis and used for a flying mission, without going into orbit.

The cosmic radiation factor is also important - at low orbit, satellites are significantly protected from the effects of cosmic particles by the Earth's hemisphere, magnetic field and upper layers of the atmosphere. However, as practice shows, modern earth electronics for industrial use can operate in interplanetary space for up to a year.

The third difference between the devices is the need to change the orbit. As a rule, small near-earth satellites do not need to change the orbit from the one on which they were launched. In extreme cases, you can use aerodynamic techniques, as it is original.decided in the company of Planet. For satellites in high orbits, correction of the orbit is already required due to the duration of the flight, and disturbing factors that begin to accumulate over time: the pressure of sunlight, the gravity of the Sun, the Moon, Jupiter and Venus. Orbit correction is a small change in the orbit by increasing or decreasing the flight speed.

As the device will start, so it will fly

The design of the interplanetary spacecraft strongly depends on the launch capabilities at the start. If there is a sufficiently accurate accelerating unit capable of immediately specifying the interplanetary probe with the desired trajectory and second space velocity, this significantly saves a lot of fuel on the device itself. If there is no suitable accelerating unit or the missile carrying capacity is not enough for it, it is necessary to pour more into the apparatus. But even if the propeller helped, the target would again have to significantly reduce the interplanetary velocity. In the case of the flight to the moon, it is necessary to reset approximately 850 m / s to enter orbit. Imagine a rocket capable of accelerating 100 kg of cargo up to the speed of the fastest jet aircraft - there is not enough fire extinguisher like in the movies.

When designing a lunar microsatellite, we considered two options for launching: passing launch into a geostationary orbit and launching into a moon transition orbit.

Geostationary is a popular orbit orbit, where 15-20 missiles fly each year. That is a great choice and a lot of opportunities for passing flight. But this is only 36 thousand km, and the moon must be flown ten times more.

The lunar transition orbit is the launch towards the moon with almost the second cosmic velocity. These launches happen about once a year. China, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea are launching the Moon, or they are about to launch, and there is some chance of jumping to the “tail” to someone. However, complex scientific launches are constantly being transferred, so you can agree on joint flight, make a satellite and wait for the main load for several years. The ideal option is to deliver our device immediately to a near-moon orbit - we do not consider it because of the low probability of finding a suitable “ride”.

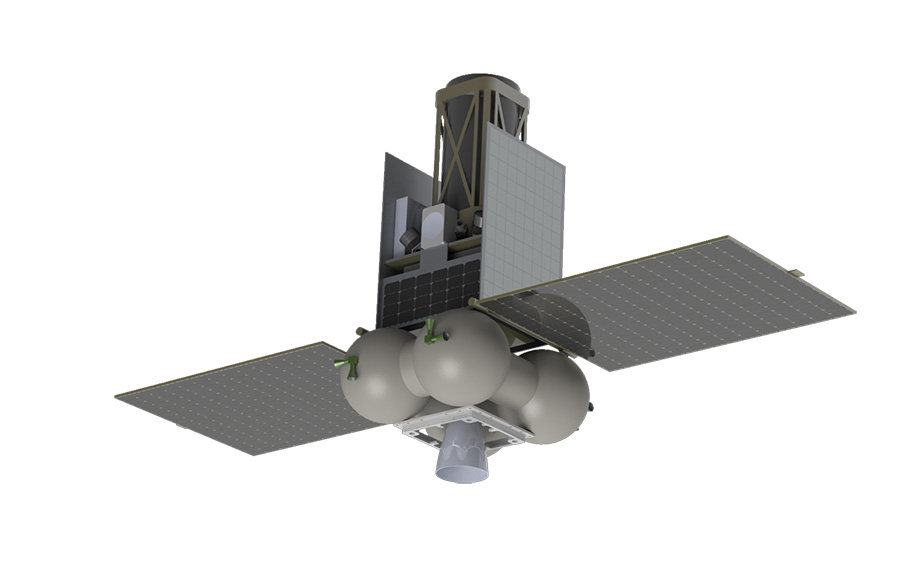

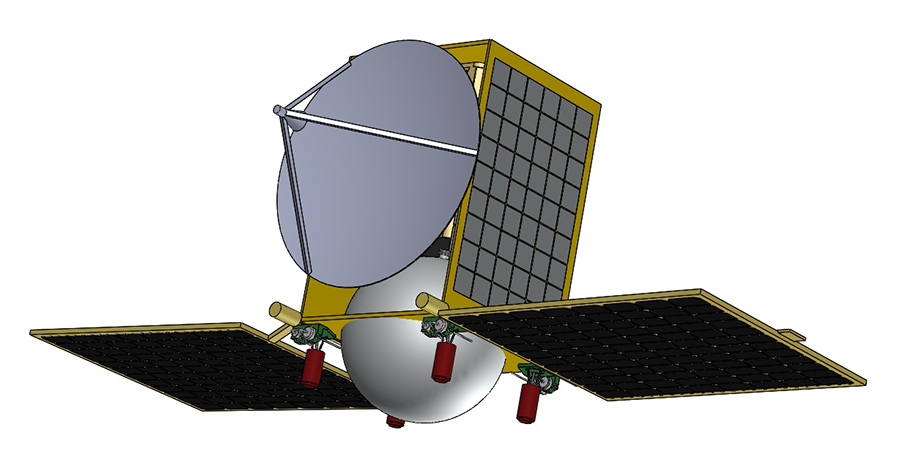

Two starting options require two different propulsion systems, with different fuel reserves. The starting mass of the two variants of the devices differed by half, and the “geostationary” version went almost 200 kg - this is no longer a microsatellite. Engines were considered hydrazine two-component (hydrazine / nitrogen tetraoxide), as the most effective of chemical for use in space. Ion and plasma engines were not considered due to the high cost, large dimensions of solar batteries and difficulties with control and navigation.

The result was a rather complicated apparatus, quite comparable with what could have been born in the KB of state enterprises.

Differences in orbits give rise to another difference - in the means of information transfer. Despite repeated experiments with laser communication in space, radio communication remains the main method of transmitting information in astronautics. The closer the device is to the Earth, the less its radio complex, its power consumption and antenna size. Therefore, the small near-earth CubeSat can easily transmit telemetry and even photographs to hams on the ground, having a very small area of solar cells and an omnidirectional antenna from a joinery roulette.

If we want to work at the Moon and transfer large amounts of data, then we will have to attend to a highly directional antenna dish with a diameter of at least half a meter and solar panels with an area of about one meter. Reception on Earth will not be able to provide for the wire from the vents - serious stations will need antennas with a diameter of several meters, and preferably several tens of meters. There are few such stations in Russia, there are dozens of them in the world, and all of them are busy with their work. It is very unlikely that we will be allocated 64-meter or 32-meter antennas.

At least you can't rely on it. You can save on ground-based facilities by increasing the diameter of the antenna on the device. But every 10 cm of the antenna diameter or the span of the satellite’s solar batteries significantly affect its mass-inertial characteristics, require more fuel, and energy consumption for orientation systems. Energy requirements increase solar batteries, the mass of batteries, which leads to an increase in mass and growth of fuel tanks - and so on to infinity ... Therefore, the development of space technology is a perpetual compromise.

In order to save mass, we have limited the antenna diameter to 40 centimeters, in the hope that by the time of launch we will find a 12-meter or even more receiving antenna on Earth. And better three, on different continents. If we don’t find it, we’ll have to transfer data at a very low speed: tens of kilobits per second, but the reception will be available to hams.

Correct orientation

Orientation in space - the next problem. The Earth can use a magnetic field, aerodynamics or other techniques. Rocket engines remain in the interplanetary space, but there is another tool that provides high-precision orientation and allows you to effectively control the position of the device relative to its center of mass - flywheel engines. These are electric motors with massive wheels, which, rotating, contribute to the rotation of the apparatus in the opposite direction. For three-axis orientation, three flywheel engines are needed, but usually four are installed — one for reserve.

Flywheel engines require only electricity for work, but they only work when they pick up speed or when it is quenched. At some point, the flywheel picks up maximum speed and becomes useless, then it must be “unloaded”, slowed down so that the device does not lose its orientation in space. It is then that rocket engines are used for unloading, and these should be engines with a very small burden, so as not to cause a strong rotation of the vehicle. Sometimes the rocket engines of the orientation system are used gas - on ordinary compressed gas, like the very fire extinguisher from the cinema, there are other constructions: thermal catalytic or electric rocket (plasma, ionic).

Our permanent designer of the lunar microsatellite, Peter Kudryashov, set himself the goal of maximally reducing the mass of the apparatus. To this end, at the last iteration of the project, they decided to abandon the flight from the geostationary orbit, stopping only at the moon transition. Another solution was the replacement of engines. The two-component propulsion system has high power and is not suitable for unloading flywheels, so the satellite required a second propulsion system for orientation. This complicated and heavier the project. Peter found an alternative solution - to put monocomponent thermocatalytic engines of average thrust. Four engines provide suitable thrust to change the orbital speed, and their separation on the sides allows the device to be oriented in pitch and yaw, roll rotation is controlled by two additional low thrust engines. Such a solution seems to be a compromise, but there are also disadvantages that have yet to be bypassed.

Difficulties arose when trying to "reconcile" rocket engines and flywheel engines. The selected flywheels, which show themselves well on near-Earth vehicles of our scale, turned out to be too weak to compensate for the rotational speed caused by the rocket engines in our scheme.

Rotational impulse of the rocket engine in pitch and yaw can be reduced by moving the engine closer to the center, but then another problem intensifies. Shoulder reduction, i.e. the difference between the axis of the engine and the central axis of the apparatus, will lead to the fact that each operation of unloading the engine flywheels will lead to some changes in the satellite orbit, and the change will change, because rocket engine thrust is variable and depends on the pressure in the boost tank.

The main factor affecting the design of the spacecraft, its dimensions, engine power, the size of solar panels - this is the payload. Those. devices for the information from which the entire launch is carried out. In our case, this is a telescope and a photosystem for shooting the surface of the moon. With her, too, there were changes that influenced the design of the device, but this is a topic for another conversation. In general, the changes are positive - the telescope was reduced, but the change led to a significant revision of the design, which again took time.

About the features of shooting the moon is still to talk separately.

I hope that soon the preliminary design of the lunar microsatellite will be completed, and we will be able to share the generalized results of the three-year + work.