Blitzscaling Course Lecture 3.1. Michael Diaring. A bit of the history of entrepreneurship and management

- Transfer

This is the introductory part of Synopsis 3 of the Stanford University Blitzscaling course lecture given by Reid Hoffman, John Lilly, Chris Ye, Allen Blue and others.

This lecture was delivered by Michael Diaring of Harrison Metal, who was also one of the first members of the eBay team.

Lecture 1: Introduction

Lecture 2.1: Startup growth stages, “family stage”

Lecture 2.2: Startup growth stages, “family stage”

Lecture 3.1. Michael Diaring. A bit from the history of entrepreneurship and management

Lecture 3.2. Michael Diaring. Questions and Answers with Reid Hoffman

Lecture 3.3. Michael Diaring. Questions and Answers with Reid Hoffman

Lecture 4.1. Ann Mura-Co: The Thunder Lizard Theory. Author value

Lecture 4.2. Ann Mura-Co: The Thunder Lizard Theory. Product, corporate and category value.

Lecture 4.3. Ann Mura-Co: Questions and Answers with John Lilly

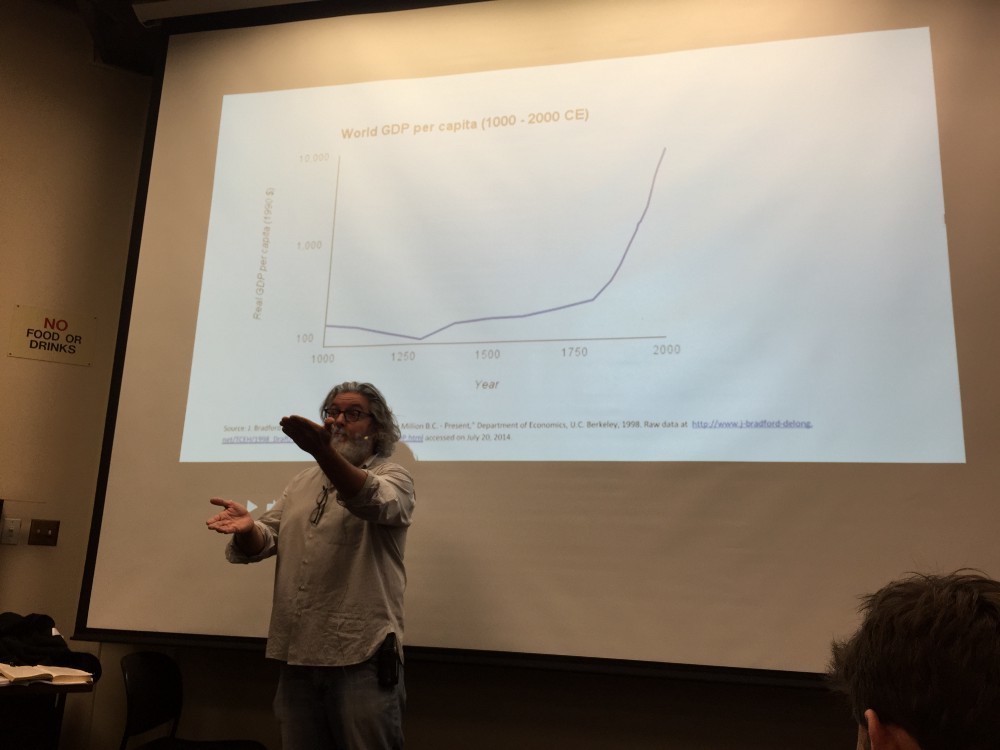

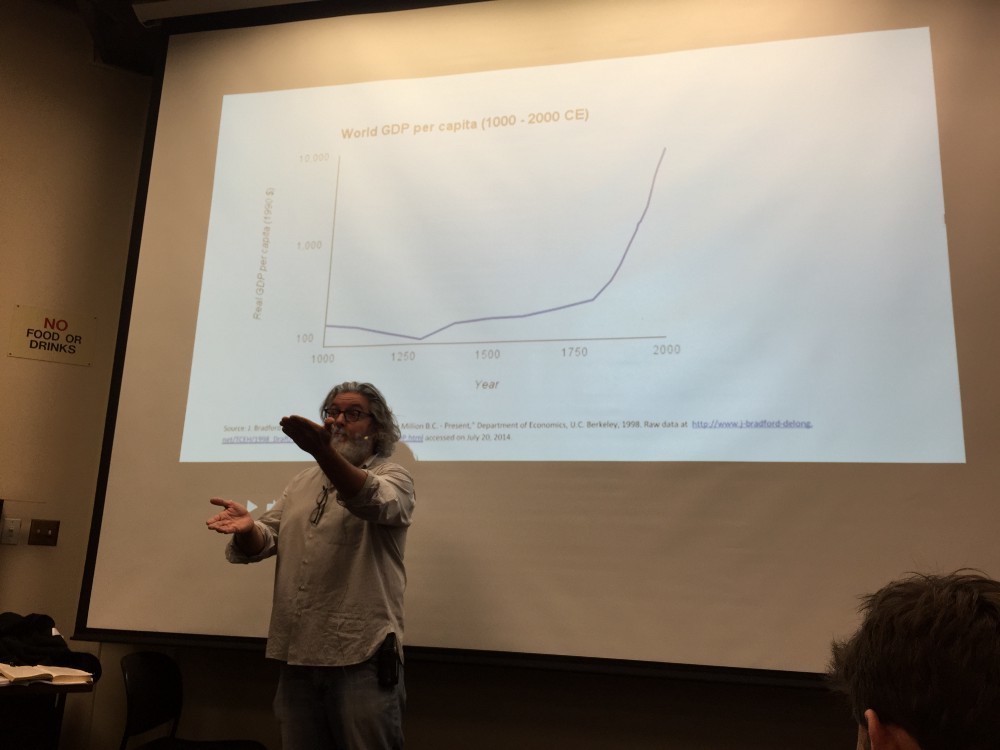

This table shows the level of GDP (gross domestic product) per capita for 1000 years (based on the constant dollar exchange rate over the entire length of the scale). A more detailed explanation of the data sources is given here.

From 1000 to 1800, the level of GDP per capita practically did not increase. After that, productivity and output have grown significantly across the globe. The turning point in this graph was the Industrial Revolution.

Why did such growth happen at this particular moment in time, and not earlier? There are several theories that the Industrial Revolution happened just then for the following reasons:

One of the philosopher-thinkers who wrote about this period of history was Joseph Schumpeter, who wrote the book “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy”. In this book, he introduced the concept of “creative destruction,” which is as follows: the

innovative contribution of entrepreneurs was the force that strengthened long-term economic growth, even though it destroyed the value of established companies that possessed, to some extent, monopoly power.

In simple words, entrepreneurs create products that completely change the way people do things and ruin existing systems. Examples of such disruptions include typewriters and computers, CDs and iPods, video cassette rentals, and Netflix.

In view of the presence of all these forces described above (cheap energy, the ability to actively move, population density), entrepreneurs during this period had more opportunities to expand their activities, and the scale of the companies created during this period of time was much larger than ever before. Examples of such companies include Carnegie Steel, Standard Oil, New York Central Railroad System, and JP Morgan.

Another notable philosopher of the time was Alfred D. Chandler, who wrote The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Chandler agreed with Schumpeter that entrepreneurs played an important role in creating new companies, but also argued that managers played an equally important role in developing the ideas of entrepreneurs themselves.

Simultaneously with the Industrial Revolution and capitalism, a new science was born - management.

The key theme that Michael Diaring promoted during the lecture was that the growth and creation of material wealth during such an entrepreneurial process gives entrepreneurs the opportunity to solve our social problems.

Despite the fact that the Industrial Revolution brought us the problems of uneven creation of material wealth, pollution, destruction of the environment, at the same time it gave us the opportunity to create a public education, improve health, increase life expectancy, and also the ability to solve our other problems. This suggests that such growth (even with subsequent problems) is better than no growth.

We must sing the entrepreneurial ideas of Schumpeter, adopt managerial capitalism and use the funds received to improve the situation of humanity.

Let's go back to our scale of per capita GDP growth and take a closer look at the 1820s, when the railway industry appeared and developed.

Railways became the main startup of the time, and entrepreneurs created and expanded their railway companies to enormous proportions. One such entrepreneur was Daniel McCallum, who worked for New York and Erie Railroad.

Daniel McCallum began as a self-taught carpenter who specialized in the construction of railway bridges, then became the curator of all bridges, patented his own kind of bridge and became the superintendent of the whole company - and all this in just over 10 years.

The key moment in his life was that when he worked on a small railway line, the work was pleasant, interesting and easy. However, when he began to manage the whole production, he only experienced pain and suffering, trying to manage a huge railway line.

McCallum's main concern was cost per mile. Current expenses grew at the same rate as the size of the railway. Where the company was supposed to see an increase in productivity (lowering the cost per mile), it saw the opposite. Communication, coordination, operations, sales - everything became more complicated as the railway grew.

When McCallum was at the top of his career, he was still trying to come up with a management model. Remember that in 1855 there were no business schools and books for dummies. There was no internship at the general manager. McCallum learned to design and build bridges, rather than manage thousands of people scattered across a continent.

When he tried to operate the 5,000-mile railway line, all of these points disappeared. All McCallum was trying to do was return everything he liked in the small line to the management of the large line.

He experimented using telegraph systems for transmitting information, creating the first modern organizational schemes, and developing various management principles based on his experience.

Surprisingly, all these questions that were asked in 1855 are relevant today, and none of the main tasks in managing large-scale companies has been resolved.

This lecture was delivered by Michael Diaring of Harrison Metal, who was also one of the first members of the eBay team.

Lecture 1: Introduction

Lecture 2.1: Startup growth stages, “family stage”

Lecture 2.2: Startup growth stages, “family stage”

Lecture 3.1. Michael Diaring. A bit from the history of entrepreneurship and management

Lecture 3.2. Michael Diaring. Questions and Answers with Reid Hoffman

Lecture 3.3. Michael Diaring. Questions and Answers with Reid Hoffman

Lecture 4.1. Ann Mura-Co: The Thunder Lizard Theory. Author value

Lecture 4.2. Ann Mura-Co: The Thunder Lizard Theory. Product, corporate and category value.

Lecture 4.3. Ann Mura-Co: Questions and Answers with John Lilly

I. A thousand-year history in one graph

This table shows the level of GDP (gross domestic product) per capita for 1000 years (based on the constant dollar exchange rate over the entire length of the scale). A more detailed explanation of the data sources is given here.

From 1000 to 1800, the level of GDP per capita practically did not increase. After that, productivity and output have grown significantly across the globe. The turning point in this graph was the Industrial Revolution.

Why did such growth happen at this particular moment in time, and not earlier? There are several theories that the Industrial Revolution happened just then for the following reasons:

- Population density: more and more people lived in cities closer to each other.

- Cheap energy: mainly in the form of coal.

- Mobility: due to cheap energy and especially the creation of a railway network, people have the opportunity to travel.

- Exchange of ideas: such mobility has led to the intensification of mutual enrichment of ideas.

II. Creative Destruction and the Governors' Revolution

One of the philosopher-thinkers who wrote about this period of history was Joseph Schumpeter, who wrote the book “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy”. In this book, he introduced the concept of “creative destruction,” which is as follows: the

innovative contribution of entrepreneurs was the force that strengthened long-term economic growth, even though it destroyed the value of established companies that possessed, to some extent, monopoly power.

In simple words, entrepreneurs create products that completely change the way people do things and ruin existing systems. Examples of such disruptions include typewriters and computers, CDs and iPods, video cassette rentals, and Netflix.

In view of the presence of all these forces described above (cheap energy, the ability to actively move, population density), entrepreneurs during this period had more opportunities to expand their activities, and the scale of the companies created during this period of time was much larger than ever before. Examples of such companies include Carnegie Steel, Standard Oil, New York Central Railroad System, and JP Morgan.

Another notable philosopher of the time was Alfred D. Chandler, who wrote The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Chandler agreed with Schumpeter that entrepreneurs played an important role in creating new companies, but also argued that managers played an equally important role in developing the ideas of entrepreneurs themselves.

Simultaneously with the Industrial Revolution and capitalism, a new science was born - management.

III. Using capitalism to solve social problems

The key theme that Michael Diaring promoted during the lecture was that the growth and creation of material wealth during such an entrepreneurial process gives entrepreneurs the opportunity to solve our social problems.

Despite the fact that the Industrial Revolution brought us the problems of uneven creation of material wealth, pollution, destruction of the environment, at the same time it gave us the opportunity to create a public education, improve health, increase life expectancy, and also the ability to solve our other problems. This suggests that such growth (even with subsequent problems) is better than no growth.

We must sing the entrepreneurial ideas of Schumpeter, adopt managerial capitalism and use the funds received to improve the situation of humanity.

IV. Transport revolution

Let's go back to our scale of per capita GDP growth and take a closer look at the 1820s, when the railway industry appeared and developed.

Railways became the main startup of the time, and entrepreneurs created and expanded their railway companies to enormous proportions. One such entrepreneur was Daniel McCallum, who worked for New York and Erie Railroad.

Daniel McCallum began as a self-taught carpenter who specialized in the construction of railway bridges, then became the curator of all bridges, patented his own kind of bridge and became the superintendent of the whole company - and all this in just over 10 years.

The key moment in his life was that when he worked on a small railway line, the work was pleasant, interesting and easy. However, when he began to manage the whole production, he only experienced pain and suffering, trying to manage a huge railway line.

McCallum's main concern was cost per mile. Current expenses grew at the same rate as the size of the railway. Where the company was supposed to see an increase in productivity (lowering the cost per mile), it saw the opposite. Communication, coordination, operations, sales - everything became more complicated as the railway grew.

When McCallum was at the top of his career, he was still trying to come up with a management model. Remember that in 1855 there were no business schools and books for dummies. There was no internship at the general manager. McCallum learned to design and build bridges, rather than manage thousands of people scattered across a continent.

V. Key management tasks at this level

- What McCallum liked about managing a small railway line:

- Personal communication with his immediate subordinates and employees

- The ability to check whether everything is done by looking with your own eyes

- The ability to see how trains move and how the system works

- Ability to show respect for each other through personal communication

When he tried to operate the 5,000-mile railway line, all of these points disappeared. All McCallum was trying to do was return everything he liked in the small line to the management of the large line.

He experimented using telegraph systems for transmitting information, creating the first modern organizational schemes, and developing various management principles based on his experience.

Surprisingly, all these questions that were asked in 1855 are relevant today, and none of the main tasks in managing large-scale companies has been resolved.

Paysto payment solutions for Megamind readers:

→ Get paid by credit card right now. Without a site, IP and LLC.

→ Accept payment from companies online. Without a site, IP and LLC.

→ Accepting payments from companies for your site. With document management and exchange of originals.

→ Automation of sales and servicing transactions with legal entities. Without an intermediary in the calculations.

→ Accept payment from companies online. Without a site, IP and LLC.

→ Accepting payments from companies for your site. With document management and exchange of originals.

→ Automation of sales and servicing transactions with legal entities. Without an intermediary in the calculations.