Why revolutionaries like spicy food, or How chili got to China

- Transfer

In 1932, the USSR sent one of its best agents, Otto Brown, a former school teacher and counterintelligence expert from Germany, to China. His task was to work as a military consultant for Chinese communists who fought in a desperate struggle for survival against the nationalists of Chiang Kai-shek .

A detailed history of Brown's adventures during the communist revolution in China contains so many unexpected turns that it would be enough for a Hollywood thriller. However, in the field of culinary history stands out one episode from Brown's autobiography. He recalls his first impressions of Mao Zedong , a man who has become the supreme leader of China.

The cunning peasant leader had one coarse, even slightly unfriendly feature. "For example, for a long time I could not get used to food with a lot of spices, for example, to hot chili peppers , traditional for southern China, especially for Hunan province , where Mao was born." The tender taste buds of the Soviet agent became the subject of Mao's mockery. “The food of a true revolutionary is red pepper,” Mao announced. “The one who is unable to bear the red pepper is unable to fight.”

Sichuan Chicken ( and recipe )

The Mao Revolution is probably not the first thing that comes to your mind when your tongue starts to burn with a serving of spicy chicken or tofu in your favorite Chinese restaurant. But this unlikely link underscores the remarkable story of red pepper.

Over the years, detectives from culinary have been tracking down the trail of red pepper, trying to understand why, after coming to the New World, he was so deeply rooted in Sichuan , surrounded by the land province of China’s southern border. “This is an amazing puzzle,” says Paul Rozin, a psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania who has studied the cultural evolution and psychological impact of food, including red pepper.

Food historians point to the hot and humid climate of the province, the principles of Chinese medicine, geographical restrictions, the plight of the economy. Recently, neuroscientists have uncovered a link between chili peppers and risk appetite. The study looks provocative, since the Sichuan people have long been famous for their rebellious spirit; Some of the most important events in modern Chinese political history can be traced back to the Sichuan origin.

As Wu Dan, a restaurant manager in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan, told a journalist: “Sichuan are a furious people. They fight quickly, love quickly and they like the same hot food as they do. ”

Red pepper from the kind of capsicumcomes from the tropics. Archaeological records suggest that it was bred and eaten, possibly as early as 5000 BC. This is usually a perennial plant with green or red fruits, capable of growing as a perennial in those regions where in winter the temperature reaches the freezing point. There are five domesticated species of pepper, but most of the food consumed in the pepper in the world refers to two types - Capsicum annuum ( pepper pods ) and of Capsicum frutescens .

The active ingredient in chili peppers is capsaicin.. When eaten, it activates pain receptors, the usual evolutionary role of which was to inform the body of dangerously high temperatures. The theory is predominant, according to which the hot taste of red pepper should scare away mammals so that they do not eat it, since the usual digestive process of mammals destroys the seeds of pepper and prevents its spread. In birds, which in the process of digestion do not destroy the seeds of red pepper, there are no such receptors. When a bird eats red pepper, it feels nothing, releases seeds and spreads the plant.

The word "chili" comes from the Nahuatl family of languages, in which, in particular, the Aztecs spoke [ and means "red" / approx. trans.]. One of the earliest variants of the Spanish translation of this word was el miembro viril, “the male member” - a seductive testimony to the male origin of the pepper). Botanists believe that red pepper comes from southwestern Brazil or southern Bolivia, but by the 15th century birds and people had spread it throughout South and Central America.

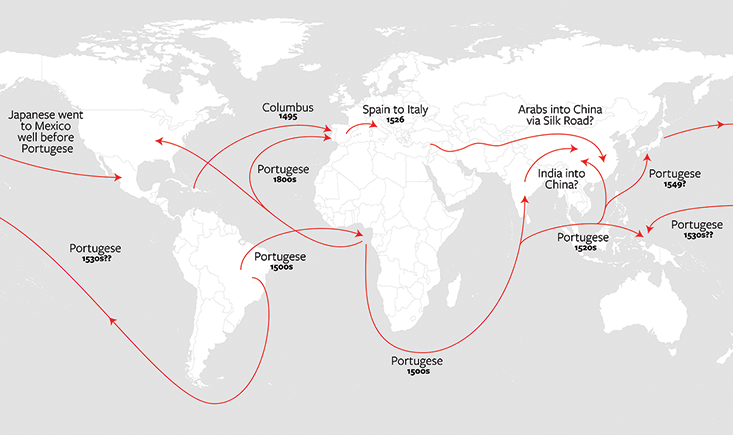

And then Columbus came on the scene. On January 1, 1493, the great explorer recorded in his diary his discovery made on the island of the Caribbean Espanyol [ later known as " Haiti " / approx. trans. ]: “Pepper used by local Indians as a spice is much more than black or meleghet [African ginger] spices.”

In the 15th century, Spain and Portugal were obsessed with searching for sea routes to Asian spice markets that would allow them to end the monopoly of Arab traders on access to such spicy values as black pepper, cardamom, cinnamon and ginger. And although Columbus was very mistaken when he decided that he had sailed to India, he achieved success by finding exactly what he was looking for.

He found a powerful and popular spice - the locals, as Dr. Columbus, Diego Chanka wrote, put pepper in all dishes. Columbus discovered a plant that probably belonged to the species Capsicum annuum or frutescens, and described it as "resembling rose bushes that give fruit long, like cinnamon."

Chili, like many other edible plants of the New World, has become a wildly popular worldwide sensation. In the hundred years that have passed since the arrival of Columbus in the New World, chili has penetrated even to such remote places as Hungary (paprika!), West Africa, India, China and Korea.

The first mention of chili peppers in Chinese annals dates back to 1591, although historians have not yet agreed on how exactly he could get to the Middle Kingdom. According to one version, it is believed that the pepper arrived in western China from India by land, along the northern route through Tibet, or along the southern route through Burma. But the first reliable descriptions of red pepper in the Chinese press appear in the eastern coastal regions, and gradually move inland, reaching the province of Hunan in the west in 1684 and Sichuan in 1749. These data support the version of the maritime arrival of red pepper, perhaps thanks to the Portuguese merchants who founded the colony near the southern coast of China on the island of Macau.

Historians and ethnogurmans are confused by the fact that other parts of China, where the red pepper came, accepted it without enthusiasm. In particular, the inhabitants of Guangzhou in the southeast rather easily abandoned its temptations, retaining their commitment, which has much more subtle taste nuances to the kitchen. But in Sichuan chilli settled for a long time. Obviously, this province was distinguished from others by a whole set of factors.

Because of its special geography, Sichuan was distinguished by a particular historical identity in China, thousands of years old. Its inhabitants are separated from their neighbors by majestic mountain ranges and rivers, while the region has a temperate climate and a fertile central plain, so adapted for agriculture that it was even called the “land of plenty”. Sichuan Province always became a refuge when something went wrong in other parts of the empire.

One of the most dramatic events in the history of Sichuan happened in the 17th century when the Ming Empire collapsed, and the Qing Empiregaining power. During this transition, a devastating set of catastrophes - riots, banditry, famine - led to mass extinction. According to some estimates, about 75% of the Sichuan population died or left the area during this period.

Over the next century, one of the most extensive mass internal migrations in the history of China has reintroduced this province. Most of the new immigrants came from two provinces in the east - Hunan and Hubei .

Historian Robert Entenman wrote his doctoral dissertation at Harvard on this migration. According to his calculations, by 1680, about 1 million people remained in the Sichuan province, but 1.7 million immigrants arrived in the period from 1667 to 1707. Therefore, almost at the same time, when the red pepper snuck into the depths of the continent to Hunan, the Hunans moved en masse to Sichuan, driven by the overpopulation of their province and economic necessity.

Red pepper map: Christopher Columbus met him in the Caribbean at the end of the 15th century. Shortly thereafter, Spanish and Portuguese traders, obsessed with controlling the spice market, spread pepper throughout the world. Red lines and dates mark the path of chili pepper from country to country.

Capsicum annuum is easy to grow in both tropical and temperate climates, and it retains its properties after drying, making it an ideal candidate for long-term storage and transportation. During the big shocks, red pepper was a relatively inexpensive seasoning compared to salt and black pepper. Sichuan people have a saying: “Hot peppers are food for the poor.” Chilli also contains a large amount of vitamin A and a significant amount of vitamins B and C. It is fragrant, nutritious, inexpensive, and easy to grow; from a pragmatic point of view, it is easy to understand the international distribution of red pepper.

Another, more provocative version of the popularity of chilli pepper says that its geographical distribution is due to its antibacterial properties. In a 1998 paper published in the journal Quarterly Review of Biology, Paul Sherman and Jennifer Billing of Cornell University found a correlation between the average temperature of a country (or region) and the number of spices used in the “traditional” cuisine of the region. The equation was simple: the higher the temperature, the more spices they eat there. According to their theory, spices performed the function of combating microbes, which is especially useful in tropical and subtropical regions, where meat very quickly deteriorates.

Over the past decade, researchers have found evidence of antibacterial properties in chili peppers, and in general, in tropical regions, red peppers consume more than in other places. Also, the Sherman-Billing thesis echoes the traditional Chinese explanation of why Sichuan and Hunan love spicy food.

In his memoir, Shark Fin and Sichuan Pepper, Fuchsia Dunlop , author of Chinese cookbooks, writes that the region’s great love for spicy dishes is due to the combined influence of climate and traditional Chinese medicine: “From the point of view of Chinese medicine, the body is an energy system, in which wet and dry, cold and hot, yin and yang must be balanced. "

In Sichuan province, it is terribly humid in winter and hot in summer. To resist wet weather, Sichuan historically flavored their diet with a warming meal — garlic, ginger, and Szechuan pepper (spices not associated with red pepper and creating a numb feeling on the tongue). When red pepper appeared, Sichuan easily adapted it to their existing kitchen.

To understand how deeply chili has come into southwestern Chinese culture, says Gerald Yang-Schmidt, an Australian cultural anthropologist who lived in Hunan Province for three years, look at the energetic disputes between Hunans and Sichuan about who is less afraid hot pepper. Both provinces make up the center of the Chinese “pepper belt” and extol the stereotype of “spicy girl” (la mei zi), who is “hot-tempered like a hot pepper,” says Young-Schmidt. On the video of the popular song “La Mei Tzu” by the Hunan singer Song Zuying, there are a lot of young Chinese girls in red clothes frolicking while collecting a huge harvest of red pepper. Sun Zuying sings:

In childhood hot-tempered girl is not afraid of hot temper.Therefore, the transition from Spice girls to the revolution may not be so big.

As an adult, hot-tempered girl is not afraid of heat.

Getting married, hot-tempered girl is afraid that her life will not be acute enough.

In the 1970s, Rozin, from the University of Pennsylvania, studied the eating habits of chili consumption by Mexicans from a small village in the state of Oaxaca . Today, he believes that the fundamental reason that people around the world eat red pepper is simple: its taste and burning sensation. But they are not born with this habit.

Unlike most of the usual types of food, chili really delivers pain when eating. This pain, according to scientists, is an artifact of evolution. When capsaicin comes into contact with nerve endings, it excites the pain receptor, the normal function of which is to determine too high a temperature. This TRPV1 receptor is needed to warn us against such foolish actions as touching burning objects or biting something so hot that it can actually damage our mouth.

Based on his research in Oaxaca, Rozin determined that eating red pepper in Mexico is an acquired habit. Children are not born with the desire to try very spicy food. There is a pepper that they are trained in the family, with the help of small and constantly increasing doses.

The genetic aspects of capsaicin sensitivity have been little studied. Some of them can be associated with the same physiological characteristics that are inherent in people with high taste sensitivity , especially people who are sensitive to bitterness. However, the initial rejection reaction can be overcome by regular use. If you grew up in a culture where everyone ate red pepper, you are most likely to get used to eating it yourself, regardless of whether your sensitivity to capsaicin is increased from birth, or if you surpass your neighbors in their thirst for adventure and strength of rebellious spirit .

However, Rozin noticed that some people, even in Mexico, eat more pepper than others. And outside the cultures traditionally committed to red pepper, you can find people who love spicy food on their own. To explain this phenomenon, Rozin invented the theory of "soft masochism." A certain person is attracted by burns - and, in his opinion, such a person can also be attracted by other activities with bright sensations.

He notes that eating red pepper can be likened to a rollercoaster ride. “In both cases, the body senses danger, followed by behavior, which usually stops such stimulation. In both cases, the initial discomfort after several repetitions turns into pleasure. "

Linguistically and historically, the connection between spices and excitement seems convincing, but evidence of Rosin’s theory appeared only a few decades after he formulated the original thesis. The missing link appeared in 2013 when two researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, John Hayes and Nadia Burns, published the work “Personal qualities predict addiction and eating spicy food” in the journal Food Quality and Preference.

Hayes is an associate professor of food science at the University of Pennsylvania, who in 2011 received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to study the genetics of the TRPV1 receptor. Nadia Burns was one of his graduate students. In the experiments conducted on 97 people, Burns found a significant correlation between people who received high marks on the scale of "seeking sensations" and people who liked the burning taste. Among the questions that determined the tendency to adventure were such as "I would have liked to be one of the discoverers of the unknown land" and "I like films with a lot of explosions and accidents).

Burns, now a post-dock at the University of California, Davis, says her data show a connection between adventure quest and craving for spicy food, which coincides with Rosin's theories "to a certain extent." Also, the data give enough provocative sex differences associated with the attractiveness of a sharp taste. Compared with women, says Burns, men may have more motivation to eat spicy food because of “third-party awards” of society: “in culture there is an idea that a man should strive for courageous actions, be strong and courageous - in general , conform to the stereotypical male characteristics ".

Does this mean that Mao was right? What is the relationship between a passion for revolution and red pepper?

Hongjie Wang, adjunct professor of history at the State University. Armstrong in Georgia specializes in Sichuan culture. In his essay "hot pepper, Sichuan cuisine and the revolution in modern China," he builds interesting data that supports what one modern Chinese culture researcher called "such a wonderful and surprising tendency to revolt" characteristic of Sichuan. Wang writes that in 1911, a protest against the imperialists ’control of the newly built railways in Sichuan led to state unrest, which ultimately led to the fall of the Qing empire - therefore, we can say that the Sichuan’s hot temper launched the entire modern Chinese political process.

In his essay, Wang emphasizes the rebellious spirit of the Sichuan. During the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)according to him, the Sichuan provided about 3.5 million soldiers to the Chinese army, which amounted to almost a quarter of the armed forces for the entire period of the war. Sichuan city of Chongqing served as the military capital of Chiang Kai-shek. What may be the most convincing - he wrote that out of 1052 generals and marshals who served in the People’s Liberation Army of China , as many as 82% come from the four provinces with the highest consumption of spicy food.

In Sichuan, Wang writes, “eating spicy food has become considered a sign of the presence of such personal qualities as courage, bravery and endurance, which are extremely important for a potential revolutionary”.

The puzzle begins to emerge. Personal qualities: moving immigrants at risk. Economy: an inexpensive and easy-to-grow version of the supplement taste in a limited diet. Weather and culture: hot humid climate, medical philosophy based on yang and yin. Everything together shows us the formation of culture, the beginning of identity.

The final touch finishing this modern act of identity formation appeared only after the Sino-Japanese war, when the Chinese elite, having fled to Sichuan from the communists and the Japanese, found themselves in exactly the same economic framework as those refugees who had immigrated to Sichuan in a few centuries before them. And they also turned to low-cost, spicy, peasant food, which the lower classes inadvertently turned into one of China’s greatest cuisines.

"A new wave of migration to Sichuan before and during the anti-Japanese war in the 1930s, finally witnessed the prosperity of Sichuan cuisine in its modern form," says Wang.

Some like it hot: in a market in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, a woman puts red pepper on the scales.

Somewhere at the end of the 19th century, a woman with traces of smallpox on her face, remaining in history, like “old Chen”, began serving her signature dish, a very spicy fried mixture of tofu and minced pork in a small shop near northern ravens of Chengdu. Mapo Tofu

Recipes“They differ, but the typical version includes fresh tofu, mixed and fried in a mixture of garlic, ginger, red pepper, green onion, tree mushrooms, water chestnut, minced pork or beef, soy sauce, rice wine, rice vinegar and Sichuan pepper. The dish can not be set aside some one definite feeling. The story tells of a combination, the interaction of flavors.

In Chengdu, to this day there is a restaurant, which is considered a direct heir to the original shop Chen. this is not surprising. Unfading popular dishes svya Ana is not only interacting with flavors. Mapo tofu offers the perfect metaphor for a society which considers itself a revolutionary and rebellious, proud of his sharpness in every sense.

The bites and burns of red pepper remind us of how peasants of southwestern China, under the influence of historical and economic forces, created culinary masterpieces based on the basic survival instinct. Out of poverty, war, and globalization trends, they created fire — for their table, and for ours.

More articles on the popular science topic can be found on the Golovanov.net website . Subscribe to updates by e-mail, via RSS or Yandex.DZen channel .

According to numerous requests, the opportunity to support the project financially is realized . Thanks to everyone who has already provided support!