Report of the Club of Rome 2018, Chapter 1.12: “From the empty world to the complete world”

- Transfer

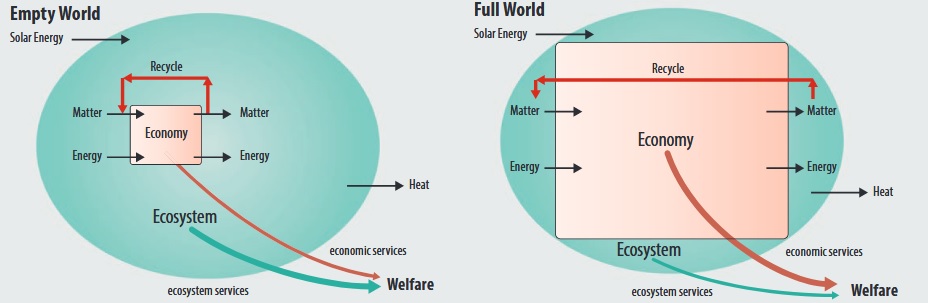

Picture. 1.18 Well-being in a complete and empty world (Source: Hermann Daly, www.greattransition.org/publication/economics-for-a-full-world )

Among economists and high-ranking government officials, there is often a statement “there is no conflict between economics and the environment. We can and must simultaneously develop the economy and protect the environment. ” It's true? Is it possible Although this is a comforting idea, it is no more than half true.

Taking into account the issues considered so far, it is quite natural that the Roman Club completes work on chapter 1 of the book with a discussion of the economy, primarily by highlighting the huge difference between empty and complete peace. The principles that guide our economies in full peace should be different than in an empty world.

1.12.1 Effect of physical growth

Human economy, as shown in Fig. 1.18 is the open subsystem of the larger ecosphere, which is finite, non-growing, and materially closed, although open for constant throughput of solar energy. When an economy grows in physical dimensions, it includes matter and energy from the rest of the ecosystem.

This means that the so-called "economy" should, according to the law of conservation of matter and energy (First Law of Thermodynamics), encroach on the ecosystem, diverting matter and energy from previous natural uses. A larger human economy (more people, goods, and landfills) means less natural ecosphere. There is a clear physical contradiction between economic growth and environmental preservation.

The fact that the economy is a subsystem of the ecosphere seems to be too obvious to emphasize. However, the opposite point of view is common in our governments. For example, the chairman of the UK Natural Capital Committee says that "as rightly emphasized in the White Paper, the environment is part of the economy and must be properly integrated into it so that growth opportunities are not lost."

But how important is this conflict between how physicists understand the laws by which the planet exists, and what do economists and governments believe in? Some people think not at all. Some people believe that we still live in the Empty World, where the economy was small in relation to the ecosphere containing (relatively empty of people and our things), where our harvesting and harvesting technologies were not very powerful, and our numbers were small. Fish multiplied faster than we could catch it, trees grew faster than we could collect them, minerals in the crust were concentrated and abundant, and natural resources were not really scarce. In the Empty World, the undesirable side effects of our production systems, which economists call "negative externalities,"

In a complete world, however, there is no huge natural waste absorber. The accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today is a prime example. Throughout the world, "external effects" are not external, but they affect people and the planet in the same way. By definition, they are not included in the cost of production as expenses, which they are.

Both neoclassical and Keynesian economic theories developed on the basis of the concept of an empty world and still embody many of the assumptions of that era. But remember in pic. 1.6: in one life, the population of the Earth has more than tripled from two billion to seven billion. Populations of cattle, chickens, pigs, soybeans, and maize grew even faster, as well as non-living populations of cars, buildings, refrigerators, and cell phones.

All these populations, both living and non-living, are what physicists call "dissipative structures." That is, their maintenance and reproduction require metabolic flow, throughput, which begins with the depletion of resources with low entropy (high structure) from the ecosystem and ends with the return of polluting waste with high entropy (high disorder) directly into the ecosphere. At both ends, this metabolic bandwidth imposes the costs necessary for the production, maintenance and reproduction of stocks of both people and wealth. Until recently, the concept of metabolic bandwidth was absent in standard economic theory, and even now its importance has been greatly diminished, despite the important contributions of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen124 and Kenneth Boulding.

The costs and benefits of moving from the empty to the full world are shown in Figure 1.18. The brown arrow from economy to welfare is economic services (benefits from the economy). They are small in an empty world, but large in a complete world. They grow at a decreasing rate (because rational beings first satisfy their most important needs — the law of diminishing marginal utility). Growth costs are represented by declining ecosystem services (green arrow), which are large in the empty world and small in the full world. It is increasingly diminishing as the ecosystem is ousted by the economy (because people - at best - donate the least important ecosystem services in the first place - the law of increasing marginal costs).

The overall welfare (the sum of economic and environmental services) is maximized when the marginal benefits of added economic services are equal to the marginal costs of sacrificed ecosystem services. In the first approximation, this gives the optimal scale of the economy in relation to the ecosphere. In addition, the physical costs of growth are greater than they are, and thus become uneconomic growth. The empirical difficulty of accurately measuring benefits and costs (especially costs) should not overshadow the logical clarity of the economic growth limit — or the impressive empirical evidence of the Global Footprint Network and the study of planetary boundaries.

The recognition of the concept of metabolic bandwidth in economics drives the laws of thermodynamics, which is inconvenient for the “growth ideology”. The first law of thermodynamics, as noted above, imposes a quantitative compromise between matter and energy between the environment and the economy. The second law of thermodynamics imposes a qualitative degradation of the environment - by extracting resources with low entropy and returning high-entropy waste. The second law thus imposes an additional conflict between the expansion of the economy and the preservation of the environment, namely, the order and structure of the economy are paid by imposing unrest and destruction in the supporting ecosystem.

1.12.2 GDP error: physical effects ignored

Another common denial of the conflict between growth and the environment is the statement that, since GDP is measured in terms of value, it does not have a physical impact on the environment. Although GDP is measured in terms of value, it must be remembered that the cost of gasoline in dollars is a physical quantity - recently about a quarter of a gallon in EU countries. GDP is the sum of all such “dollar values” that are bought for final use, and therefore is a weighted index of physical quantities. GDP, of course, does not quite correlate with the bandwidth of resources, but for material-dependent creatures like us, the positive correlation is quite high. The prospects for an absolute “separation” of resources from GDP seem limited,

Of course, opportunities for decoupling should be actively sought through technology. However, Jevons Paradox describes the tendency of a person to consume more of what has become more efficient, outweighing much of the savings from efficiency and potentially leading to even higher levels of resource consumption in a growth economy. This is not a denial of the real possibilities of green growth.

Environmental economists distinguish growth (a quantitative increase in size through the accretion or assimilation of a substance) from development (a qualitative improvement in design, technology, or ethical priorities) and advocate for development without growth — qualitative improvement without a quantitative increase in resources beyond an environmentally sustainable scale. In § 1.1, an example of an LED was mentioned that provides more light with much less energy. Therefore, it can really be said that there is no necessary conflict between quality development and the environment. But, of course, there is a conflict between quantitative growth and the environment. GDP accounting combines growth and development, as well as costs and benefits. This number that confuses as much as specifies.

Economic logic tells us to invest in a limiting factor. Does production limit chainsaws, fishing nets or sprinklers, or the size of forests, fish stocks, or fresh water? The economic logic has not changed, but the identity of the limiting factor. The old economic policy of producing more chainsaws, fishing nets or sprinklers is currently largely uneconomical. Investments should go to natural capital, which is now the limiting factor. In the case of fisheries, this means reducing the catch so that the population can increase their previous levels.

Traditional economists have responded to this change in the limiting factor in two ways: first, by ignoring it — by continuing to believe that we live in an empty world; secondly, arguing that human and natural capital are substitutes. Even if natural capital is less than before, neoclassical economists argue that this is not a problem, because human capital is an “almost perfect” substitute for natural resources. However, in the real world, what they call “production” is actually a transformation. Natural resources are transformed (not increased) by capital and labor into useful products and wastes.

Although improved technologies can certainly reduce resource use losses, as well as facilitate their processing, it is difficult to imagine how a fund of transformation agents (capital or labor) can replace or replace the stream of what is being transformed (natural resources). Can we make a ten-pound cake with one pound of ingredients, just using more cooks and ovens?

Although a sonar investment can help find the remaining fish in the sea, this is hardly a viable replacement for the fact that there are actually more fish. At the same time, the capital value of fishing vessels, including their sonar, collapses as soon as the fish disappears. Thus, throughout the world, certain types of growth become unprofitable.

1.12.3 Again, the fallacy of GDP: consider costs as benefits

Finally, it is increasingly recognized that maximizing GDP, which has never been intended to measure public welfare, is not the proper goal of national policy. Although no measure satisfies all goals, GDP has acquired enormous power to influence national and international economic policies thanks to a broad consensus on its use over the years and in countries. GDP interprets all expenditures as positive and does not distinguish between welfare improvement and welfare decline activities.

For example, an oil spill increases GDP due to the costs of refining and recovery, while this obviously reduces overall well-being. Examples of other activities that increase GDP include natural disasters, most diseases, crimes, accidents and divorces. GDP is more closely correlated with productivity (cost) than measured wealth or self-esteem of happiness (benefit).

GDP also does not take into account many components that increase wealth, but are not related to monetary operations and therefore go beyond the market. For example, the act of collecting vegetables from the garden and cooking them for family or friends is not included in the GDP. However, the purchase of such food in the aisle of a grocery store’s frozen food involves the exchange of money and is considered a subsequent increase in GDP. A parent who stays home to raise a family or volunteer is not included in the GDP, and yet they make a potential key contribution to the welfare of society.

In addition, GDP does not take into account the distribution of income between individuals, which has a significant impact on individual and social well-being. GDP does not matter whether one person or corporation receives all income in the country, or whether it is evenly distributed among the population. However, an increase in the income of a poor person in the amount of one dollar gives more additional wealth than an increase in the income of a rich person by one dollar.

And yet, even with all the problems associated with GDP, it is the most frequently used indicator of the overall efficiency of a country. Using GDP as a criterion, the world economy has grown eight to ten times since 1950, which is a significant increase in physical throughput. The reason for the further use of GDP as a performance indicator is that it goes hand in hand with paid employment - and this is of extremely high value in our societies.

Over the past few decades, many alternative indicators have been proposed, as researchers sought to combine economic, environmental, and social elements into a common framework that would reflect real net progress (see 3.14).

To be continued...

For the translation, thanks to Jonas Stankevichus. If you are interested, I invite you to join the “flashmob” to translate a 220-page report. Write in a personal or email magisterludi2016@yandex.ru

More translations of the report of the Club of Rome 2018

Preface

Chapter 1.1.1 “Various types of crises and feelings of helplessness”

Chapter 1.1.2: “Financing”

Chapter 1.1.3: “An Empty World Against Full Peace”

Chapter 2.6: “Philosophical Market Doctrine Errors”

Chapter 3.1: “Regenerative Economics”

Chapter 3.2 : “Development Alternatives”

Chapter 3.3: “Blue Economy”

Chapter 3.4: “Decentralized Energy”

Chapter 3.5: “Some Success Stories in Agriculture”

Chapter 3.6: “Regenerative Urbanism: Ecopolis”

Chapter 3.7: “Climate: Good News, but Big problems "

Chapter 3.8:" The economy of a closed cycle requires a different logic "

Gla Va 3.9: “Fivefold Resource Performance”

Chapter 3.10: “Bit Tax”

Chapter 3.11: “Financial Sector Reforms”

Chapter 3.12: “Economic System Reforms”

Chapter 3.13: “Philanthropy, Investment, Crowdsors and the Blockchain”

Chapter 3.14: “Not a Single GDP ...”

Chapter 3.15: “Collective Leadership”

Chapter 3.16: “ Global Government "

Chapter 3.17:" Actions at the National Level: China and Bhutan "

Chapter 3.18:" Literacy for the Future "

"Analytics"

- "Come on!" - the anniversary report of the Club of Rome

- The anniversary report of the Club of Rome - embalming capitalism

- Club of Rome, jubilee report. Verdict: “The Old World is doomed. New World is inevitable! ”

- Hour: Report of the Club of Rome. Orgies of self-criticism

About #philtech

#philtech (технологии + филантропия) — это открытые публично описанные технологии, выравнивающие уровень жизни максимально возможного количества людей за счёт создания прозрачных платформ для взаимодействия и доступа к данным и знаниям. И удовлетворяющие принципам филтеха:

1. Открытые и копируемые, а не конкурентно-проприетарные.

2. Построенные на принципах самоорганизации и горизонтального взаимодействия.

3. Устойчивые и перспективо-ориентированные, а не преследующие локальную выгоду.

4. Построенные на [открытых] данных, а не традициях и убеждениях

5. Ненасильственные и неманипуляционные.

6. Инклюзивные, и не работающие на одну группу людей за счёт других.

Акселератор социальных технологических стартапов PhilTech — программа интенсивного развития проектов ранних стадий, направленных на выравнивание доступа к информации, ресурсам и возможностям. Второй поток: март–июнь 2018.

Чат в Telegram

Сообщество людей, развивающих филтех-проекты или просто заинтересованных в теме технологий для социального сектора.

#philtech news

Телеграм-канал с новостями о проектах в идеологии #philtech и ссылками на полезные материалы.

Подписаться на еженедельную рассылку

1. Открытые и копируемые, а не конкурентно-проприетарные.

2. Построенные на принципах самоорганизации и горизонтального взаимодействия.

3. Устойчивые и перспективо-ориентированные, а не преследующие локальную выгоду.

4. Построенные на [открытых] данных, а не традициях и убеждениях

5. Ненасильственные и неманипуляционные.

6. Инклюзивные, и не работающие на одну группу людей за счёт других.

Акселератор социальных технологических стартапов PhilTech — программа интенсивного развития проектов ранних стадий, направленных на выравнивание доступа к информации, ресурсам и возможностям. Второй поток: март–июнь 2018.

Чат в Telegram

Сообщество людей, развивающих филтех-проекты или просто заинтересованных в теме технологий для социального сектора.

#philtech news

Телеграм-канал с новостями о проектах в идеологии #philtech и ссылками на полезные материалы.

Подписаться на еженедельную рассылку