IBM labs learn how to get 10-centimeter graphene sheets

Graphene is one of the most promising carbon-based materials. So, graphene can be used to make a transistor capable of operating at a frequency of 427 gigahertz, or a photosensor that is 1000 times more sensitive than usual. Unfortunately, so far graphene can only be obtained in the form of scales of a fraction of a millimeter in size or in the form of films of a larger size, but consisting of several layers. At the same time, the cost of such graphene is still very high.

At the Thomas Watson IBM Research Center, they developed a technology for producing single-layer graphene sheets up to 10 centimeters in size and applying them to a silicon substrate. This technology can become the basis for mass production of graphene and the appearance on the market of electronic devices based on it.

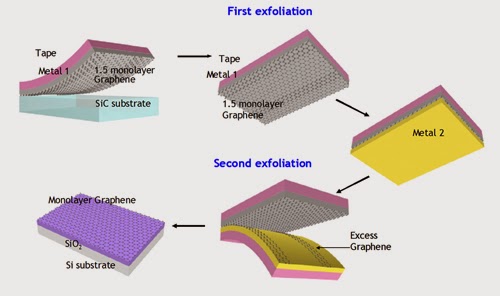

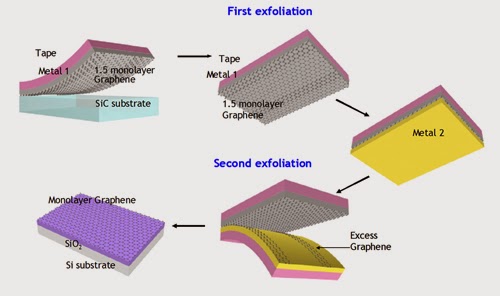

The essence of the new method for producing graphene is shown in the illustration and consists in the use of materials that “stick” to graphene with different strengths. First, a film with a thickness of one to several atomic layers of graphene is formed on a silicon carbide substrate by thermal decomposition. Using a thin film coated with nickel, graphene comes off the substrate. This process was known before, however, such graphene contained sections of several layers that impaired its characteristics. The fact is that the uppermost, surface layer is almost perfect, however, “extra” pieces stick to it, formed under the main sheet.

IBM researchers have added another step to the process - re-peeling pieces of graphene adhered to the main layer. This is done using a gold-coated film. Graphene adheres to gold better than carbon, but worse than nickel. Thanks to this, it is possible to clean the graphene film from excess pieces without damaging it and transfer it to the silicon substrate. 99% of the surface of the resulting graphene sheet has an ideal structure. The process can be repeated again and again, separating from the silicon carbide crystal layer by layer.

According to an article by Nature magazine on the prospects of graphene, modern silicon transistors will reach the theoretical limit of their capabilities as early as 2021. The transition to graphene will open a completely new era - the frequency of electronic devices can reach terahertz.

At the Thomas Watson IBM Research Center, they developed a technology for producing single-layer graphene sheets up to 10 centimeters in size and applying them to a silicon substrate. This technology can become the basis for mass production of graphene and the appearance on the market of electronic devices based on it.

The essence of the new method for producing graphene is shown in the illustration and consists in the use of materials that “stick” to graphene with different strengths. First, a film with a thickness of one to several atomic layers of graphene is formed on a silicon carbide substrate by thermal decomposition. Using a thin film coated with nickel, graphene comes off the substrate. This process was known before, however, such graphene contained sections of several layers that impaired its characteristics. The fact is that the uppermost, surface layer is almost perfect, however, “extra” pieces stick to it, formed under the main sheet.

IBM researchers have added another step to the process - re-peeling pieces of graphene adhered to the main layer. This is done using a gold-coated film. Graphene adheres to gold better than carbon, but worse than nickel. Thanks to this, it is possible to clean the graphene film from excess pieces without damaging it and transfer it to the silicon substrate. 99% of the surface of the resulting graphene sheet has an ideal structure. The process can be repeated again and again, separating from the silicon carbide crystal layer by layer.

According to an article by Nature magazine on the prospects of graphene, modern silicon transistors will reach the theoretical limit of their capabilities as early as 2021. The transition to graphene will open a completely new era - the frequency of electronic devices can reach terahertz.