The course of lectures "Startup". Peter Thiel. Stanford 2012. Lesson 7

- Tutorial

This spring, Peter Thiel ( by Peter Thiel ), one of the founders of PayPal and the first investor FaceBook, held a course at Stanford - "Start-up". Before starting, Thiel said: “If I do my job correctly, this will be the last subject that you will have to study.”

One of the students of the lecture recorded and posted the transcript . In this habratopic SemenOk2 translates the seventh lesson. Formatting 9e9names . Astropilot Editor

Lesson 1: Challenging the Future

Lesson 2: Again as in 1999?

Lesson 3: Value Systems

Lesson 4: Last Step Advantage

Lesson 5: Mafia Mechanics

Lesson 6: Thiel Law

Lesson 7: Follow the Money

Lesson 8: Presenting an Idea (Pitch)

Lesson 9: Everything Is Ready, But Will They Come?

Session 10: After Web 2.0

Session 11: Secrets

Session 12: War and Peace

Session 13: You Are Not a Lottery Ticket

Session 14: Ecology as a Worldview

Session 15: Back to the Future

Session 16: Understanding Yourself

Session 17: Deep Thoughts

Session 18: Founder - Victim or God.

Occupation 19: Stagnation or Singularity?

Lesson 7. Follow the money

I. You and venture capital

Many people creating a new venture have never come across venture capitalists. Founders who really interact with venture capitalists do not need to do this at the initial stage. First, you team up with the founders and get to work. Then, perhaps, you attract friends, relatives, or “business angels” to invest. If you still need to increase the amount of capital, then you need to know the principle of venture capital. Understanding how the venture capitalist thinks about money, or, in some cases, how he does not think about it and, accordingly, loses it, is very important.

Venture capitalists appeared in the late 40s. Prior to this, wealthy individuals and families often invested in new enterprises. But the idea of pooling the funds that professionals would invest in companies at the initial stage of development was born in the 40s. Sand Hill Road, the forerunner of Silicon Valley, appeared in the late 60s, along with leaders in the field - Sequoia capital, Kleiner Perkins, and Mayfield fund.

In general terms, a venture firm operates as follows. You collect a lot of money from people called limited partners. Then you take money from this fund and invest in portfolios of companies that you consider promising. If all goes well, then over time, these companies will become more expensive, and everyone will make a profit. Therefore, venture capitalists play a dual role, encouraging limited partners to give them money, and then find successful (in the long term) companies for their return.

Most of the profits are returned to limited partners as return on investment. Venture capitalists, of course, have their share. A typical model, called 2-and-20, means that the venture company charges an annual fee for managing funds - 2% of the fund and receives 20% of the profit without taking into account the initial investment. Theoretically, 2% of the commission for managing funds is already enough to continue the work of a venture company. In practice, the amount can be much larger. Under the 2-and-20 model, a fund of $ 200 million will earn $ 4 million in management fees. But, of course, we must admit that the real income expected by venture capitalists comes from a 20% share of the profit, which is called “deferred” (“transferred”).

Venture funds have been operating for several years, since it usually takes years for the companies you invested in to grow in value. Most investments in such funds either do not bring money or fall to zero. But the idea is that a successful company will more than return all your investments. As a result, your fund will become more than the originally invested funds of limited partners.

There are many criteria for a successful venture capitalist. You must have the ability to reasonably evaluate companies, identify prominent entrepreneurs, etc. But there is one particularly important factor that few understand. Undoubtedly, the fundamental principle of the venture capitalist is to use the power of exponential growth in their interests. This is just basic math, which may seem strange. Just as arithmetic at the 3rd grade level - knowledge of not only the number of shares received, but also the division of them into outstanding shares - is a decisive moment for understanding share capital, mathematics of the 7th grade level - knowledge of the exponent (exponent) - is necessary for understanding venture capital.

Einstein’s famous quote - compound interest - is the most powerful force in the universe. The viral growth of companies can be seen as confirmation of this idea. Successful enterprises tend to exhibit an exponential arc. It is possible that they are increasing at a rate of 50% per year, which summarizes over several years. Growth can be more or less sharp. But this model - a significant period of exponential growth - is the foundation of any successful technology company. And during this exponential period, company valuations tend to increase exponentially.

So, consider a hypothetical successful fund. Over time, the fund invests all available funds and the growth of the investment portfolio stops. This happens pretty quickly. Successful investments are growing exponentially. Summarize all investments during the life cycle, and get a curve in the form of the letter J. In the beginning, there is no profit. In addition, you need to pay management fees. But then exponential growth happens, at least in theory. Since you start below zero, the main question is when will you be able to “emerge”. Many foundations fail.

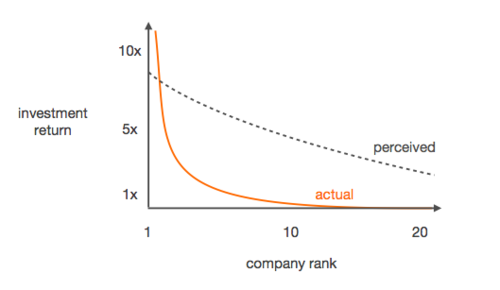

To answer this main question, you need to ask one more: what is the distribution of profit on invested capital in a venture capital fund? The naive answer would be this: just rank the companies in descending order based on the income they received in relation to the amount of investment. People tend to divide investments into three groups. Bad companies make no profit at all. Mediocre firms probably make a profit in the amount of investments, so you won’t lose much, but you won’t earn much either. And finally, great companies earn an average of 3-10 card profits.

But this model lacks a key point: the actual profit is extremely asymmetric. The more the venture capitalist understands this asymmetric scheme, the more successful he is. Unsuccessful venture capitalists usually think that the dashed line is flat, i.e. that all companies are created on an equal footing, and some simply fail, others stagnate or grow. But in fact, you get a distribution based on an exponential law.

(investment return - return on invested capital, perceived - perceived, actual - actual, company rank - category of companies)

An example will help clarify. If you look at the 2005 Founders Fund, you will find that the best investments are more effective than all the others combined. And investments in the second best company in the list were about as valuable as in all the others, from the third to the end of the list. The same dynamics was maintained in general throughout the fund. This is the distribution based on the exponential law in practice. In a first approximation, a venture capital portfolio will only bring money if it turns out that your best investment in a company will cost more than your entire fund. In practice, it’s quite difficult to be as profitable as this venture fund, if you do not reach these numbers.

PayPal was sold to eBay for $ 1.5 billion. Investors who funded PayPal at the initial stage had a rather large share, and as a result, their investment cost almost as much as their entire fund. The rest of the fund's portfolio was not so profitable, therefore, to one degree or another, they reached the breakeven level using PayPal. But PayPal B Series investors did not cover the costs of their fund, despite the fact that they successfully managed the investment in PayPal. Like many other venture capital funds in the early 2000s, their fund lost cash.

The fact that the return on invested capital is based on the principle of exponential distribution allows us to draw the following conclusions. First: you need to remember that in addition to commissions for managing funds, you receive money only if you return all invested funds with an increase. At the very least, you must achieve 100% of the volume of capital. So, taking into account the distribution according to the exponential law, you should ask: "Is there such a rational scenario in which our share in this company will cost more than the total capital?"

Second conclusion: taking into account the exponential distribution, you should be quite concentrated. If you invest in 100 companies to try to secure yourself through volume, then you are doing something wrong. There are few lines of business in which you can get the required high degree of confidence. The best investment model is 7 or 8 promising companies, from which, in your opinion, you can get 10-fold profit. In theory, mathematics offers the same thing if you try to invest in 100 different companies, which, in your opinion, will bring 100 times profit. But in practice, it does not look more like investing, but like buying lottery tickets.

Despite the fact that the exhibitor is taught in a high school mathematics course, it is quite difficult to develop this type of thinking. We live in a world in which usually nothing happens exponentially (exponentially - approx. Translator) Our ordinary life experience is fairly linear. We extremely underestimate exponential things. If you conduct a retrospective study of the Founders Fund portfolio, then one heuristic rule that worked just incredibly well is that you should always exercise your right to proportionally increase your share of investment in a portfolio company when an intelligent investor seeks to grow the company in the current round of investing. Conversely, the study showed that you should not increase your investment with a frozen or decreasing investment portfolio value.

Why are there so many wrong estimates of company value? One hunch: people do not believe in exponential distribution. They do not intuitively believe that return on investment can be so spasmodic. Therefore, when you have an increase in the price of shares with a large increase in value, many, or even most venture capitalists are inclined to believe that such an increase is too large, and therefore they underestimate the shares. Practical example: Imagine that you are working in a startup. You have an office. You have not yet reached the exponential growth phase. Then comes the exponential growth. But you can not take this change into account and underestimate the important shift that has occurred, simply because you are still in the same office and a lot of things look the old way.

Financing should be avoided if the value of the shares in this round does not increase. This means that, in the opinion of the involved venture capitalists, the situation could not deteriorate so much. Such rounds are initiated by those people who think they can get, say, a 2-fold return on investment. But in reality, often things go very badly, and as a result, the share price will never rise. This heuristic rule should not be taken purely mechanically or as an immutable investment strategy. But in fact, this rule is pretty well confirmed, so at least it will make you think about distribution based on an exponential law.

The concept of exponential and exponential distribution is important not only for understanding venture capital. The same principles apply in everyday life. Many things, such as key decisions in your life or the decision to start a business, lead to a similar distribution of results. We tend to think that the range of possible outcomes is small - a little better, a little worse. In reality, the scatter is much more significant.

Not always, of course. Sometimes a flatter perceived curve, oddly enough, pretty closely reflects reality. If, for example, you thought about working in the postal service, then the perceived curve will probably be correct. You will get what you see. And there are a lot of things like that. But it is also true that we, for one reason or another, have been taught to think basically this way. Therefore, we tend to incorrectly assess the situation where the perceived curve, in fact, does not accurately reflect reality. The context of a technology startup is one such place. In fact, the deviation from the line in terms of distribution for a technology startup is really significant.

This means that when you focus on the size of your stake in the company, you should change your perception. In conditions of exponential distribution, the place your company occupies on the curve is no less important or even may mean much more than the size of your share.

All things being equal, it is better to have 1% of the company than 0.5%. But the 100th employee on Google has received far more than the average CEO of a regular venture capital company over the past ten years. Distribution should be seriously considered. You could use this as an argument against joining a startup. But don't go that far. Exponential distribution simply means that you need to seriously think about where the company will fit on the curve.

The opposite view is that the standard perception is reasonable or at least not unreasonable, since in fact the distribution curve is arbitrary. It claims that you are just a lottery ticket. This is not true. Later we will talk about why this is not true. For now, it’s sufficient to emphasize that the actual curve is an exponential distribution. You do not need to know all the details and the deep meaning of what this means. But it is important to realize this. Even a modicum of understanding of this parameter is extremely valuable.

II. View from Sand Hill Road

Peter Thiel: The thing we should talk about is the secrets that venture capitalists resort to for profit. In fact, most do not make a profit. So let's talk about it.

Roylof Botha: The profitability of venture capital is well known. The average yield has remained at a fairly low level for several years now. According to one version, when in the 90s the venture capital companies made good money, this was an important event for almost blindly following the recommendation on investing more and more money in venture capital enterprises. Therefore, there may be an excessive amount of money in this industry, and for most companies it is difficult to make money.

Peter Thiel:Paul, what should entrepreneurs do so that venture capitalists do not take advantage of them?

Paul Graham: In essence, venture capitalists have no predatory intentions. Y-Combinator Venture Fund is a minor league bench. We direct people directly to venture capitalists. Venture capitalists are not evil or deceit, nothing like that. From the point of view of concluding a good deal, not a bad one, and this applies to any transaction, the best way to get a good price is competition. Venture capitalists must compete among themselves to invest in your enterprise.

Peter Thiel:We discussed in this lesson how frightening competition can be. But perhaps it is not so bad when the venture capitalists enter the competition. In practice, you will never involve only one investor. Most likely, you will be interested in either two investors, or not a single one. Here's a cynical explanation for this: most venture capitalists are unsure of their ability to make decisions. They are simply trying to imitate the decisions of others.

Paul Graham:But investors are also interested in waiting. To wait means to be able to get more information about this company. Therefore, waiting is bad for you only if the founders raise the price while you wait. Venture capitalists are looking for startups that will become the next Google. They cool about 2x return on investment. But most of all, they don’t want to miss a chance like Google.

Peter Thiel: How not to become a money-losing venture capitalist?

Roelof Botha:Since the distribution of the results of investments in startups follows an exponential law, you can’t just expect that you will make a profit simply by writing checks. That is, you cannot just offer investment as a commodity. You should be able to help the company in various ways, such as using your connections on their behalf or helpful advice. Sequoia Foundation has been active for over 40 years. You cannot get the same profit just by providing cash.

Paul Graham:Leading venture capital funds are forced to make decisions on their own. They cannot follow someone else because everyone follows them! Look at the Sequoia Foundation. This fund is very disciplined. This is not a business school student fraternity company that sorts founders to select guys like Larry and Sergey. Sequoia carefully prepares the research documentation for the proposed investment ...

Roylof Botha: But the research is brief. If you are preparing or think that you need a document of 100 pages, then you will not see forests behind the trees. You should be able to concentrate information on 3-5 pages. If there is no short description, then there will be nothing.

Peter Thiel:Even within the private sector, perhaps there is a kind of exponential law that should be guided. For example, if a startup insists on making a profit in various ways, this is a problem. The exponential law of income distribution states that one source of profit will dominate. Perhaps you have not yet discovered this specific source of income, and of course, you need to think about this. But the key point is making a profit in the way A. The investor is scared of making a profit in the ways from A to E.

Roylof Botha: LinkedIn is an exception that confirms the rule. It has three streams of income, fairly equal. In fact, this is not anywhere else. At the very least, this is very unusual.

Peter Thiel:Do Y-Combinator companies follow an exponential distribution method?

Paul Graham: Yes. True

Peter Thiel: Incubators can be unreliable. Max Levchin founded this. He had a rather long cycle, it seems, even an annual one. This is done for some crazy intercompany dynamics. All these people go sailing in the same boats, but due to the dynamics of the exponential law they end up in completely different ships. The separation is pretty sharp. Understanding why different people achieve different results can be very difficult.

Roelof Botha:People do not always appreciate and do not understand the rapid increase in the value of an enterprise when it "takes off." They underestimate the massive asymmetry of return on investment. They heard that the company is now valued at billions of dollars, and are puzzled, since it was worth $ 200 million just six months ago. Another explanation for exponential growth is the assumption that Silicon Valley venture capitalists are crazy.

Peter Thiel:The most successful increase in the value of PayPal shares resulted in a 5-fold increase in the value of the company. But such an increase in value was far-sighted. Those. it wasn’t like that: take x and multiply by 5, but there was a comment that the cost is appropriate, thanks to the promising future. Real value is always in the future. In the absence of a clear perspective that you can show, people hold on to a well-defined past. That’s how you get the refusal: “How can it cost 5x when 3 months ago it was x?”

Paul Graham:You can even say that the whole world more and more takes the form of an exponential law. Now people are divided into many different camps. If everyone had to work for one of 10 companies like General Motors - as perhaps this is happening in Japan - this would straighten the curve of the exponential law and make it straight. The distribution would be grouped because everyone is connected. But in the presence of many sagging and in the separation of people, extremes are formed. And we can bet that this trend will continue in the future.

Roelof Botha:Another thing that people struggle with is the notion that it is possible to create such large companies very quickly, often in one night. At the beginning of PayPal, there were about 300 million Internet users. Now there are 2 billion of them. We have more mobile phones, there is cloud data processing. There are many opportunities for growth. Therefore, there is a qualitative difference in the ability to have such a huge impact as an entrepreneur.

Question from the audience: Does the distribution exponentially reflect an increased, reduced or unchanged estimate of the price of shares or show a specific place for the company on the distribution curve?

Peter Thiel:Firstly, it’s important to note that when you join a startup or launch it, you invest in it. All your money in one pocket. But thanks to exponential distribution, your investors are in the same place as you. In a way, the money of venture capitalists is also in your pocket. They have a little more pockets than you, but again, thanks to the exponential law, not so much. Venture capital is not a direct investment, where you can get a solid 2- or 3-fold return on investment.

One can rephrase this question: is this not market inefficiency? My retrospective testing requirement is that full proportional financing should be provided whenever one of your companies, led by a visionary venture capitalist, spends an increase in stock prices.

Roylof Botha: I do not have the information that you need, but my intuition says that this is true. But only for the best venture capitalists. If the venture capitalist is not smart enough or far-sighted, the reverse may well happen. Companies may get too much money, may have 15 months to start. They become complacent, they lack critical thinking. After 9 months, something unforeseen happens and this leads to a crisis. And no one else wants to invest in them.

Peter Thiel: Even if you take into account the dilution of capital, things will go well with you if the stock price rises in all rounds. But even a slight decrease in stock prices leads to failure, mainly due to the discord among the major players. If you are going to conduct business with a not very smart investor who gives you a very high rating, you should take this money only if it is the last money that you are going to take.

Question from the audience: Does the shape of the distribution curve change or does it depend on the time or stage of the investment?

Peter Thiel:The curve is quite steep along the entire length of the climb. Founders Fund tries to invest in 7-10 companies for each fund. Their goal is to get 10 times the return on investment. Is it difficult to get such an investment return? Equally difficult to come from $ 10 million to $ 100 million, from $ 100 million to $ 1 billion, or from $ 1 billion to $ 10 billion. It’s harder to get a trillion out of $ 100 billion, because the world is not so big. Apple has a capitalization of $ 500 billion and Microsoft $ 250 billion. There the exponential distribution upward is simply unbelievable.

The same is likely to apply at the level of business angels. The investment environment of business angels is a kind of saturated site for sponsors-investors, especially at present, with the adoption of the Law on the Forced Startup of Business Startups (JOBS Act). But, according to some opinion, business angels are even less familiar with the dynamics of the exponential law than the rest, and therefore they usually overestimate a single company.

Roelof Botha:There is a 50% bankruptcy rate for venture capital firms. Think of such a curve. Half of them will come to naught. At the late stage of financing, there is already an increase in investment, which makes the situation not so radical. Some people achieve 3-5 times the return on investment with a very low level of bankruptcy. But even this model of venture capital is still subject to the exponential law. The curve is just not so steep.

Question from the audience: What if the value of your business is $ 50 million, and you can’t increase it?

Paul Graham:This assumption is absurd. Increase it if you want it. There is no such thing as a fixed company size. Companies are not inherently restrictive in nature. Look at Microsoft or Apple. They started with the production of small products. Then, as success was achieved, their scale grew, and units appeared.

Let me explain that it is absolutely great to have a low limit of aspiration. If you just want to have a $ 50 million company, that's great. Just don’t take venture capital, or at least don’t tell venture capitalists about your plans!

Peter Thiel:You would be of great concern to investors if you put a slide at the end of your presentation saying that you are going to sell your company for $ 20 million in 18 months.

Question from the audience: What happens if you have spent many rounds and things are going badly, and your current investors do not want to invest more?

Paul Graham: With this development, you are wasting your time at investor meetings. Their opportunity costs associated with many rounds are very high. People can stand only a dozen meetings. A little more and they will explode. Therefore, they will try to sell you.

Peter Thiel:Such an inadequate result causes other costs associated with the termination of numerous boards of directors. There are significant reputational costs associated with replacing boards of directors. So there is a big gap between the public image - stories about how venture capitalists kindly pay attention to all their companies and their equal treatment - and reality in accordance with exponential law.

Roelof Botha: And maybe even worse when troubled companies can actually take up most of your time than successful ones.

Peter Thiel:This is a waste of resources. There are various options for action in such situations. At one extreme, you simply write checks and exit the business. At the other extreme, you are helping anyone who needs help in the amount he needs. The unspoken truth is that the best way to make money is to promise to help everyone, but then only help those who provide the best return on investment.

Question from the audience: Bill Gates did not attract financing and as a result received a large stake in Microsoft. If a startup can break through on its own instead of attracting venture capital, what should it do?

Paul Graham:A venture capitalist can lend you a guarantee of future growth. You can wait until your profit is high enough to finance x. But if you are good enough, someone will give you money to do x now. If there is competition, you may need to urgently do x. Therefore, if you do not make mistakes, then venture capital can really help you.

Roelof Botha: We would not do business if it required a simple writing of checks. Entrepreneurs implement this approach when they create companies. But the board of directors and venture capitalists can roll up their sleeves, offer advice and provide the necessary assistance. They may be ready to help entrepreneurs. But you must neither overestimate nor underestimate this important feature.

Paul Graham: The simple support of a large venture firm will help you open many doors and will greatly assist in hiring employees.

Peter Thiel: If your business does not need urgent development, you can reconsider the need to attract venture capital funds. But if the business has dynamics according to the principle “the winner gets everything”, if the principle of distribution according to the exponential law comes into play, then you need venture capital. It is worth giving 25% of your business if this allows you to occupy your niche.

Question from the audience: Does Sequoia and other leading venture capital firms offer tougher preliminary agreements in case of additional support measures? Or is all this hype about creating extra non-monetary value simply bloated?

Roelof Botha: Not bloated. In fact, everything is individual. Who are you doing business with? Can you trust them? I would not send my brother to most venture capital firms. But some are quite good. You really should know well the people you intend to work with. In fact, you are entering into a long-term relationship.

Just look at yourself from the side. Perhaps the answer is in your Stanford diploma. These “signals” will help you a little. The same is true if you rely on the support of certain venture capitalists. The name has a great value, apart from other important things like establishing the right acquaintances. It is often difficult to determine the strategic direction in which to move, but you will come to this yourself yourself in various interesting and useful ways. Even if we do not have answers, then most likely we have already encountered similar problems and can help entrepreneurs to reflect on these issues.

Question from the audience:Right now, entrepreneurs are trying to sell the company for $ 40 million in 2 years or less. The point is to sell insignificant developments, instead of creating complex systems for a long time. What is the reason and what is the result? The greed of entrepreneurs? Venture capitalists don't value technical innovation?

Paul Graham: I do not agree with the premise of a lack of innovation. 50 millionth companies apply new technical solutions. My applied. We mainly created Internet applications. We did complex development on LISP, while the rest wrote CGI scripts. And frankly, 50 million is a lot. Not all of us can sell the company for $ 1.5 billion, after all ... [looks at Peter].

Peter Thiel:Let me rephrase the question: are venture capitalists looking for quick ways to generate income? Are we getting companies with more diffuse capital than we should?

Paul Graham: I don’t think that investors have such a big influence on what the companies actually do. They do not disagree, and do not say no, do this great thing x, instead of this stupid y. Of course, a mass of people is trying to imitate what they consider simple. Y-Combinator will probably filter thousands of Instagram-like apps in the next cycle.

Roelof Botha:If someone came to me, and I would understand that he is trying just to urgently sell the company, I would run away. But most of the founders did not graduate from a business school with a specialization in financing mechanisms that accurately calculate which direction will bring them the most profit. Most good founders are people who solve problems that upset them. Google grew out of a research project implemented from disappointment at AltaVista.

Peter Thiel:One strange conclusion for the dynamics of the exponentially curve is that people who create really good companies, as a rule, hesitate to sell them. This is almost always the case. And this is not due to a lack of offers. Paradoxically, people who are largely motivated by money do not make a lot of money in the world of exponential law.

Question from the audience: If most of the money comes from people who don’t want to earn a lot, how do you deal with this paradox as an investor?

Roelof Botha:Consider a simple 2 x 2 matrix: on one axis you have founders that are simple or difficult to deal with, and on the other axis you have an exceptional founder and an ordinary founder. It is easy to figure out in which quadrant venture capitalists make money.

Question from the audience: If the principle of exponential distribution is so critical, how did the Y-Combinator fund succeed?

Paul Graham: The point is a very sharp fall. In fact, the Y-Combinator fund gets the first choice from a very good national and even international pool of candidates.

Peter Thiel:I would not like to be either a supporter or an opponent of the Y-Combinator fund. Something they do well, but something, maybe worse. If you go to an incubator, and this is not Y-Combinator, then this is perceived as a negative recommendation. It's like a Berkeley diploma. It's just not Stanford. You can tell a confusing story about what you studied there, as your parents had a large mortgage or something like that. But this is a strong negative signal, which is hard to forget about.

Question from the audience: Do you finance founders or ideas?

Paul Graham:Founders. Ideas simply show the mindset of the founders. We are looking for stubborn and inventive people. The key point is precisely the combination of these qualities. Stubbornness is in itself useless. You can stubbornly and incessantly bang your head against the wall. But it’s better to be stubborn in finding a door, and then ingeniously go through it.

Roelof Botha: There are rarely people who can clearly and concisely identify a problem and formulate a coherent approach to solve it.

Peter Thiel: That is why it is very important to conduct a thorough study of the founding team.

Roelof Botha:You can learn a lot about the founders by asking about their choice. What key choices have you encountered in your life and what decisions have you made? What alternatives did you have? Why did you enter this institution? Why did you move to this city?

Paul Graham: Another consequence of the exponential law is that having gaps on many issues is normal, as long as it doesn’t touch on really important directions. The Apple guys were out of control and dressed poorly. But they understood the importance of microprocessors. Larry and Sergey realized the importance of the search.

Peter Thiel:Isaiah Berlin wrote an essay entitled Hedgehog and the Fox. The essay is dedicated to the line of the ancient Greek poet: foxes know a lot of little things, and hedgehogs know one important thing. People tend to think that foxes are better because they are agile and have extensive knowledge. But in business, if you have to choose between two, it's better to be a hedgehog. But you should still try to learn a lot of little things.

Question from the audience: You mentioned “visionary venture capitalists” in the retrospective testing example. Who are these visionary venture capitalists?

Peter Thiel: Common suspects. The next question.

Question from the audience: What keeps you awake at night? What are you most afraid of?

Paul Graham:I am afraid that due to some event, I personally will have even more work. What is your greatest Roylof fear? Andressen Horowitz?

Roelof Botha: Suffice it to say that you are as good as your next investment.

Question from the audience: Will an entrepreneur be able to attract venture capital if he has already received investments and went bankrupt?

Paul Graham: Yes.

Roelof Botha: Prior to PayPal, Max had two failures, right? Well, this is a myth that bankruptcy is a stigma. In some countries, such as France, this is true. Bankrupt is looked down upon. But in the United States to a much lesser extent, and in Silicon Valley in particular.

Peter Thiel:But still, one should not easily relate to commercial failures. Nevertheless, the price of failure is quite high.

Paul Graham: Mostly, it depends on why this crash happened. Dalton Caldwell killed the music business. Everyone knows that his guilt is not here. It's as if the mafia shot you. You cannot be blamed for this.

Roelof Botha: Sometimes experience with unsuccessful startups can do a good job for an entrepreneur. If you could learn a lesson from this, then perhaps this will add inspiration or understanding to the launch of the next company. There are many examples. But, of course, you don’t need to specially fill up the project for the sake of experience that can be useful to you in the future.

Question from the audience: Are you funding a one-person team?

Paul Graham:Yes. Drew Houston was the only member of the team. We advised him to find a co-founder. He found. And it worked out well.

Peter Thiel: The basic team of two-person founders with equal shares usually works the best. Or sometimes it makes sense to have one outstanding founder who will be undeniably better than anyone else.

Paul Graham: Four is already too much.

Peter Thiel:Think of co-founders in terms of exponential law. Having one founder means losing half of the company. Two means giving up 2/3 of the company. But if you choose the right people, then it is likely that with them you will achieve an investment return of two or three times more than you would have achieved without them. So in the world of exponential law, the co-founders work pretty well.

From the translator:

I ask for translation errors and spelling in PM. I also remind you that this text is a translation, its content is copyright, and the author's opinion may not coincide with mine.

I repeat once again that I translated SemenOk2 . Formatting 9e9names . Editor of Astropilot . All thanks to them.