Employers are tracking computers, going to the toilet, and now also emotions; Is your boss following you?

- Transfer

From implantation of microchips to wearing tracking bracelets and sensors that can catch fatigue and depression, new technologies allow employers to more and more intrusively monitor employees. Do we need to worry about this?

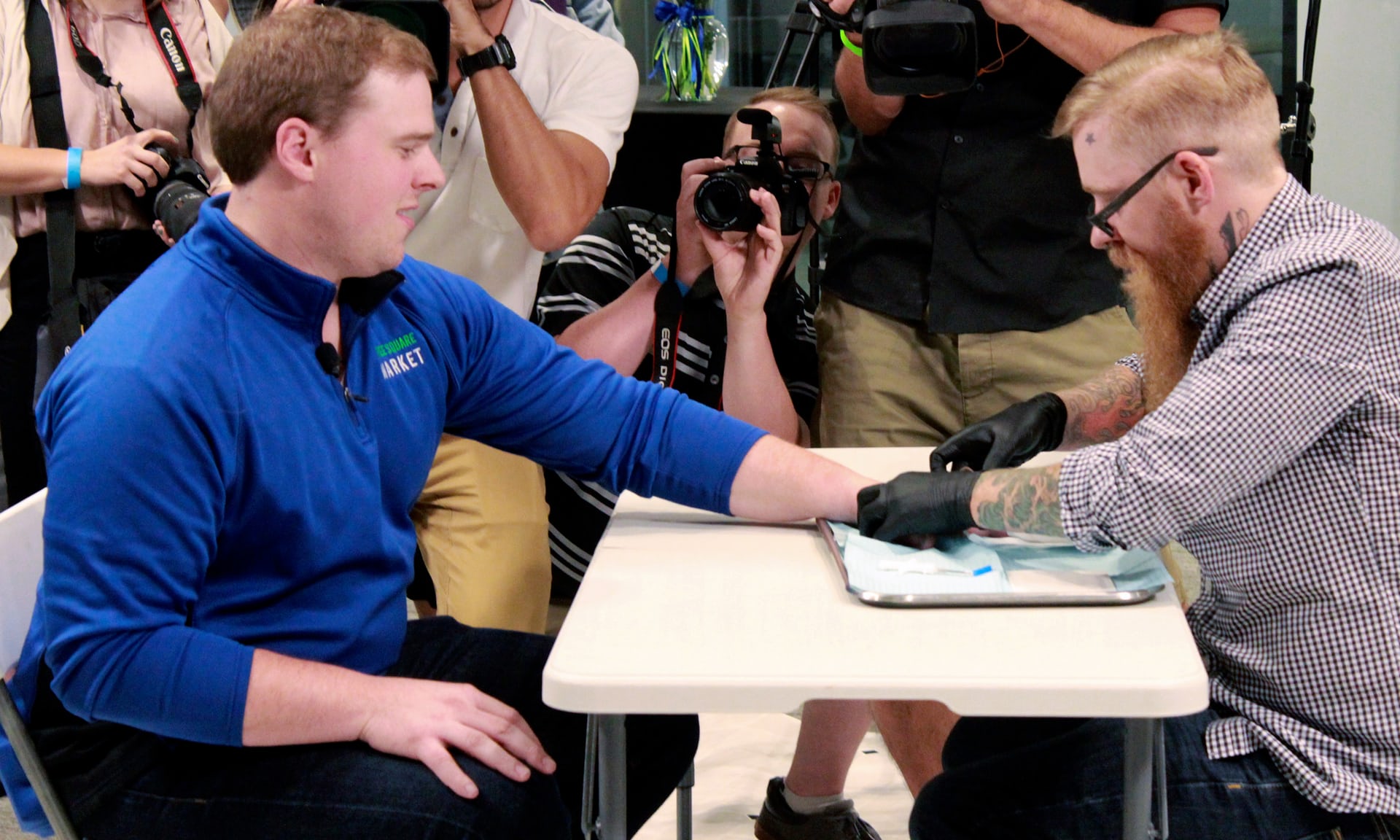

Last year, the American company marked dozens of workers with microchips. At the “chip party” that hit the headlines of world newspapers, staff lined up to implant a device the size of a grain of rice under their skin between their thumb and forefinger. At first, Todd Westby, director of Three Square Market, thought that five or six people would be called upon to volunteer — he, a couple of directors, a few IT professionals. But out of 90 people working at headquarters, 72 are already equipped with chips; Westby's chips in both hands. They can be used for opening doors, authorization on computers and payment in the company's vending machines.

Can he imagine how such an initiative penetrates into many other companies? “Not necessarily,” he says. At least for now. He believes that this is partly due to the generation. “You may not want to implant your chip, but if you are a millenial , it will not cause you questions. They think it's cool. ” The chip can be used in a different way: two months ago, a company (whose main business was selling vending machines and kiosks) began chipping people with dementia in Puerto Rico. If one of them goes for a walk and gets lost, the police will be able to scan the chip, “and they will receive all the medical information, what medicines they can and cannot be given, their identity.” So far, Three Square Market has gleaned 100 people, but plans to reach 10,000.

The company has just launched a mobile application that connects the chip with the GPS in the phone, which allows you to track the person's location with the implant. Last week, she began using it with people who had been released from prison for a trial period instead of ankle bracelets, which Westby describes as “abusive and degrading”. Can he imagine that his company will start tracking its workers with chips on GPS? “No,” he says. “There is no reason for that.”

Tony Dana, vice president of Three Square Market, gets his implantable microchip

Not all firms will agree with this. Technological companies are inventing even stranger and more intrusive ways of tracking labor. Last week, the Times wrote that some Chinese companies use sensors built into workers' helmets and hats to scan their brainwave and detect fatigue, stress, and even emotions like anger. She added that one electric company uses a brain scan to determine how many breaks a worker makes and how long they take. The technology is used on machinists of high-speed trains to "identify fatigue and loss of attention." And although such a technology may have legitimate security applications — a similar project was tested on Crossrail employees who used fatigue-tracking bracelets — it's easy to imagine

In February, it was reported that Amazon received patents for a bracelet, not only tracking the location of an employee in a warehouse when they collect things for shipment, but also reads the movements of his hands, and informing them with a buzz or vibration that they were not reaching for the wrong thing. In the patent description, Amazon indicates that the bracelet is capable of "tracking the effectiveness of sorting incoming items into places intended for them by the warehouse worker."

There are companies selling products that can regularly take snapshots of work, track keyboard input and use of websites, and even take pictures of employees themselves using webcams from their computers. And working from home does not protect against this, since all this can be done remotely. The software can track the use of social networks, analyze the language or work on the phones of employees, tracking the work of protected applications like WhatsApp. Employees can be equipped with badges that track not only their location, but also the tone of voice, the frequency of statements at meetings, their interlocutors and the duration of conversations.

Employees were always watched in the workplace, and technology was always used for this. But if once it was a foreman with a stopwatch, or a device for punching cards at the entrance and exit from work, now “all physical work has moved into the field of digital technology,” said Andre Spicer, a professor of organizational behavior at Kass Business School. “They keep track of things that could not be traced in the past, for example, the number of keystrokes, the direction of their gaze on the screen, the use of certain words. And now surveillance goes beyond the workplace. ”

Some Chinese companies use sensors to measure employee fatigue and emotional levels.

How much is all this legal? In Britain, employers are allowed to track sites visited by employees, says Philip Landau, a partner in labor law at Landau Law Solicitors. “However, the device on which the visit is being monitored must be fully or partially owned by the company. Employees are also required to inform in advance that their online activities will be monitored, as well as to report on the employer's attitude towards social networks. ” It is also allowed to track keystrokes, although employees must also be informed about this. “In companies where this system works, bosses can talk with subordinates about the fact that the number of keys pressed by them is too low,” Landau says. “It is worth noting that a high number of clicks does not necessarily mean high labor efficiency, and vice versa.”

Theoretically, employers can use a webcam on an employee’s computer to find out when he is at work, “but for such tracking an excuse is needed and you should be notified in advance. You must also be notified of what the photographs will be used for and how they will be stored. ” Regarding GPS tracking, “the company can track any of its vehicles provided to employees. However, the collected data can only be used for company management purposes. You can not turn on the device with GPS, if the employee uses the vehicle for personal purposes. "

James Bloodworth worked as an “assembler” for a month — he was looking for products ordered by people — at Amazon in March 2016, collecting material for his book “Hired: Six Months Under Cover in Britain for Low Wages” [Hired: Six Months Undercover in Low-Wage Britain ]. “We carried a portable productivity device with us,” he says. It directed workers to the goods they needed to find on the shelves of one of the huge warehouses of Amazon. “Every time I took a product, a countdown timer started that measured the time it took to find the next thing — that was how productivity was measured.” Bloodworth says that supervisors told people about their productivity; he was warned that he was among the 10% worst. “We also received warnings about the need to increase productivity through the device. We were constantly monitored and evaluated. I found that it was impossible to achieve the goals of productivity without running around the warehouse — however, they were forbidden to run, but were punished for running. But if we were behind the indicators, we were also punished. ” There was no feeling, he says, "that they treated us like people." Workers had to go through the framework of metal detectors at the beginning and end of the working day, as well as during the passage to the rest areas. He says that going to the toilet was marked as “idle time,” and once he found someone's bottle of urine on one of the shelves. Workers had to go through the framework of metal detectors at the beginning and end of the working day, as well as during the passage to the rest areas. He says that going to the toilet was marked as “idle time,” and once he found someone's bottle of urine on one of the shelves. Workers had to go through the framework of metal detectors at the beginning and end of the working day, as well as during the passage to the rest areas. He says that going to the toilet was marked as “idle time,” and once he found someone's bottle of urine on one of the shelves.

Amazon's distribution center worker

Amazon claims that scanning devices are “often found in warehouses, logistics centers, supermarkets, department stores, and other businesses, and are designed to help people complete their tasks,” and the company “ensures that all of its employees have access to toilets located close to their place of work. " He adds: “Employees are allowed to use the toilet as needed. We do not track their toilet breaks. ”

According to Bloodworth, some of his colleagues were annoyed at the level of tracking - “but for the most part it was cynicism and dismissal. Most of the people I have met have worked recently or were looking for another job. Each job was temporary, and the turnover was constant. " Did Bloodworth see the future? Will all of us track our bosses in the coming years? Probably, he says. “Based on the feedback on the book, it became clear that people say that they still automate work as a result, or workers will have to be more flexible; such is the future, and it is inevitable, which seems to me quite dangerous. Amazon can go unpunished due to its political choices and the weakness of the trade union movement. I think that other companies will equal on Amazon, having seen the success of their business model, and will try to reproduce it. ”

For his book Working with Phones, Jamie Woodcock, a sociology specialist at the Oxford Internet Institute, worked for six months in a call center. He says that the sense of surveillance "arises from the moment you enter the company. TV screens demonstrate the relative performance of all employees. Managers collect data on almost all aspects of your work. Every phone call I made was recorded and stored in a digit. From the point of view of tracking, it’s like the ability to view each movement made by a person on the assembly line and evaluate its quality. We all make mistakes, we all have bad days, but such surveillance can be used to retroactively dismiss people and also make them feel that they can be fired at any moment. ”

Tracking is embedded in many work classes that form the so-called "part-time economy" [Eng. gig economy is an environment in which temporary work is often found, and organizations enter into short-term contracts with employees]. It is not easy to protest against continuous observation when you are desperate for work. Spicer was surprised by how readily people agree to this in higher paying places. “In the past, prisoners were obliged to wear tracking bracelets, and now we voluntarily put on fitness trackers or other tracking devices that our employers give us, and in some cases even pay for this privilege.” Companies such as IBM, BP, Bank of America, Target and Barclays offered their employees to wear Fitbit trackers.

It's all part, says Spicer, “ideas about striving for self-improvement and optimization. Many technologies are designed to provide feedback on your effectiveness not only to your superiors, but also to you personally. I think they are also treated like something cool or trendy, so it’s not surprising that they are accepted so readily. ”

Spicer watched the process shift “from tracking something like e-mail to tracking human bodies — essentially, the arrival of biological tracking. Tracking your vital signs, emotions, moods ". Regarding the practice of chipping employees in the Three Square Market, he says: “You can imagine how this is slowly spreading. You can imagine how the employer asks you to provide him with your DNA or other data. ”

Deliveroo is already tracking the effectiveness of its couriers.

Surveillance can be applied with positive goals. In the financial industry, it is necessary (and required by law) to prevent insider trading. It can be used to prevent harassment and intimidation, and also to eliminate bias and discrimination. One interesting study from last year tracked emails and work efficiency, and used sensors to track behavior and interaction with management. It was found that women and men behave at work in almost the same way. This contradicts the view that women are not promoted because they are less proactive or interact less with leaders, and they just need to “push”.

And yet, Woodcock says, “we need to have a public discussion about whether work should be a place where you are being watched.” This is especially urgent, perhaps in relation to work, where people pay little and people feel insecure. “If you work in a part-time economy, you have a smartphone,” indicates Woodcock, and this smartphone can be used to spy on you. “I think that since many of these workplaces lack traditional forms of organization or trade unions, management can introduce such things with relatively little resistance.”

Union of Independent Workers of Britainwell aware of the problems of tracking and data collection. James Farrar is the chairman of his joint driving unit, and the Uber driver, who won the lawsuit against the company last year on driver rights. “They really collect a lot of information,” he says. - One of the daily reports is how well you work with acceleration and deceleration. You assign a rating. The question is: why do they collect this information? ”Uber also tracks the phone’s“ unusual movement ”when a person is driving (that is, if someone is using their phone while driving), and, of course, it tracks car and driver by GPS.

“What worries me is that this information is fed to the distribution algorithm,” he says. “We must have access to the data and an understanding of how it is used.” If some indicator of the quality of my driving skills is introduced into the algorithm, it may be that they will offer me less valuable work and not give the most valuable customers — who knows? ”And this fear is not without reason - the food delivery company Deliveroo is already doing something like, tracking the effectiveness of their couriers, and began to offer "priority access" in the distribution of shifts to people who "provide the most consistent and quality service." Uber, however, claims it only tracks performance to ensure a “smoother, safer ride. This data is used to inform drivers of their habits and do not affect future travel requests. ”

Not all snooping is bad, says Farrar. In some cases, he would like to increase its number. He was somehow attacked by a passenger, and he calls to install cameras in all vehicles, partly for the safety of the drivers themselves. “Observation technology has a role to play,” he says. Ironically, when Farrar went to meet with Uber to discuss the attack, the company forced him to turn off his phone to prove that he was not recording their conversation.

Only registered users can participate in the survey. Sign in , please.