Before Netscape: Forgotten Web Browsers of the Early 1990s

- Transfer

Does anyone remember Erwise? Viola? Cello? Let's remember.

When in 1980 Tim Berners-Lee arrived at CERN, the famous European laboratory for particle physics, he was hired to update the control systems of several particle accelerators. But the inventor of the modern web page almost immediately saw the problem: thousands of people constantly came and went to the research institute, many of whom worked there temporarily.

“It was quite difficult for programmers on a contract to try to understand the systems, both human and computing, that controlled this fantastic playground,” Burners-Lee wrote later. “Most of the critical information existed only in people’s minds.”

Therefore, in his free time, he wrote some software to address this shortcoming: a small program that he called Enquire. It allowed users to create “sites” - pages that looked like index cards filled with information and had links to other pages. Unfortunately, this application, written in Pascal, worked on the CERN proprietary OS. “A small number of people who saw this program considered it a good idea, but no one used it. As a result, the disc was lost, and with it the original Enquire. ”

After a few years, Berners-Lee returned to CERN. This time he restarted his World Wide Web project so as to increase the likelihood of his success. On August 6, 1991, he published an explanation for the WWW in the alt.hypertext user group. He also released the libWWW library code, written by him with an assistant, Jean-Francois Groff. The library allowed participants to create their own web browsers.

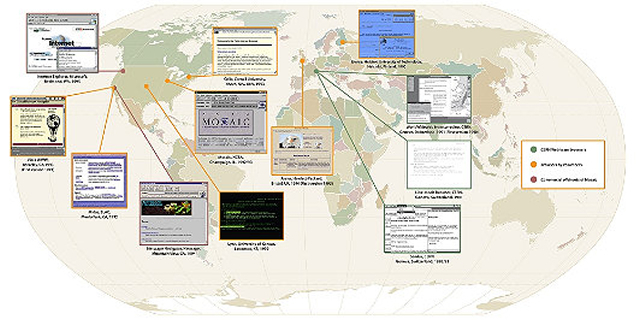

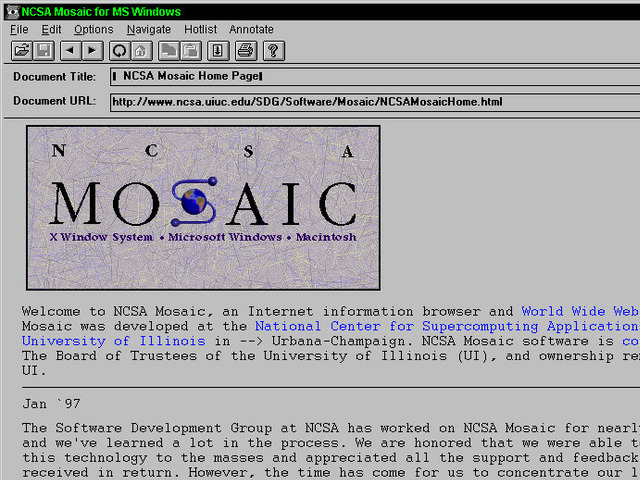

“Their work — more than five different browsers in 18 months — saved a web project that had problems with funding and launched a community of web developers,” said the celebration of this anniversary at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California. The most famous of the early browsers was Mosaic, written by Mark Andrissen and Eric Bina of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA).

Mosaic soon turned into Netscape, but it was not the first browser. The map compiled by the museum gives an idea of the global scale of the early project. What is surprising about these early applications is that they already contain many of the features of later browsers. And here’s a tour of the web browsing apps they were before they became famous.

CERN Browsers

Tim Berners-Lee's first browser, called WorldWideWeb from 1990, was both a browser and an editor. He hoped that future browser designs would go in that direction. CERN has collected a reproduction of its contents. The screenshot shows that by 1993 there were already many characteristics of modern browsers present.

The main limitation of the software was that it worked on the NeXTStep OS. But shortly after WorldWideWeb, CERN's math intern Nicola Pellow wrote a browser that could work in other places, including UNIX and MS-DOS networks. In this way, “everyone could go online,” explains Internet historian Bill Stewart, “which at that time basically consisted of the CERN phone book.”

CERN early web browser, approx. 1990

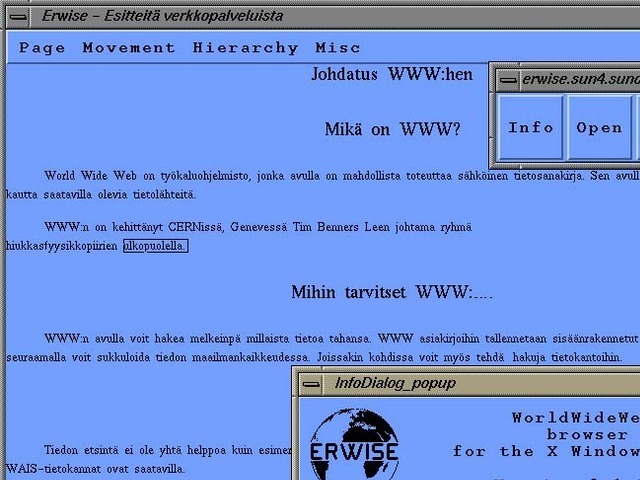

Erwise

Then Erwise appeared. It was written by four Finnish college students in 1991, and was released in 1992. Erwise is considered the first browser with a graphical interface. He also knew how to search for words on a page.

Berners-Lee wrote a review of Erwise in 1992. He noted his ability to work with different fonts, underline links, allow users to go to other pages by double-clicking on a link, and support multiple windows.

“Erwise looks pretty smart,” he announced, although there’s a mystery in it, “a strange frame around a single word in a document, like a button or form for selection. Although it is neither one nor the other - perhaps it is something for future versions. "

Why didn’t the application take off? In an interview given later, one of the creators of Erwise noted that there was a deep recession in Finland at that time. There were no angel investors in the country.

“At that time, we would not be able to create a business based on Erwise,” he explained. - The only way to make money was to continue development so that Netscape eventually bought us. However, we could reach the level of the first Mosaic, having worked for a short time. We needed to finish Erwise and release it on several platforms. ”

Erwise Browser

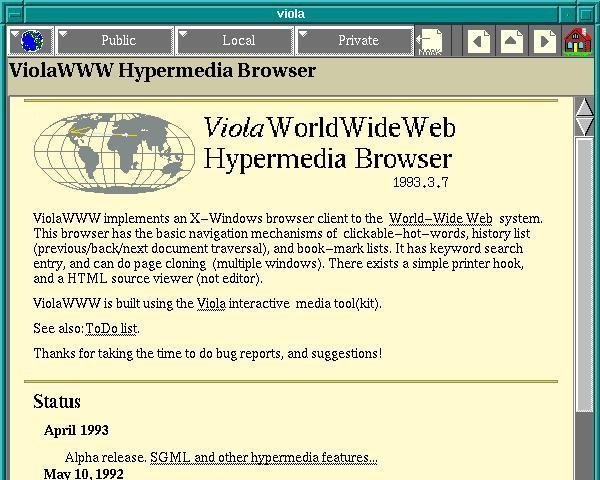

Violawww

ViolaWWW was released in April 1992. Developer Pei-Yuan Wei wrote it at the University of California at Berkeley using the Viola scripting language, which worked under UNIX. Wei didn’t play the cello, “it just happened because of the catchy abbreviation” of the Visually Interactive Object-oriented Language and Application, as James Gillis and Robert Kayau wrote in their WWW story.

Wei was apparently inspired by an early Mac program called HyperCard, allowing users to create matrices from formatted documents with hyperlinks. “Then HyperCard was a very interesting project, graphically, and even these hyperlinks,” he recalled later. However, the program “was not global and only worked on a Mac. And I didn’t even have my Mac. ”

But he had access to the UNIX X-terminals at the Berkeley experimental computing center. “I had instructions for HyperCard, I studied it and just used the concepts to implement them in X-windows.” Just, quite impressive, he implemented them using the Viola language.

One of the most important and innovative features of ViolaWWW was that the developer could include scripts and "applets" in the page. This anticipated the huge wave of Java applets that appeared on sites in the late 90s.

INWei's documentation also noted various browser flaws, the main one being the lack of a PC version.

- Not ported to PC platform.

- HTML printing is not supported.

- HTTP is not interruptible, not multi-threaded.

- Proxies are not supported.

- The language interpreter is not multithreaded.

“The author is working on these issues, etc.,” Wei wrote at the time. And yet, “a very neat browser, suitable for use by anyone, very intuitive and straightforward,” concluded Berners-Lee in his review . "Additional features will not be used by 90% of real users, but these are the functions that experienced users need."

ViolaWWW Hypermedia Browser

Midas and Samba

In September 1991, physicist Paul Kuntz visited CERN from Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC). He returned with the code needed to run the first North American web server on SLAC. “I was just at CERN,” Kuntz told the chief librarian, Louis Addis, “and I discovered such a wonderful thing that one friend, Tim Berners-Lee, is developing.” This is exactly what you need for your base. ”

Addis agreed. The chief librarian posted a key research base on the web. Physicists from Fermilab did the same a bit later.

Then in the summer of 1992, SLAC physicist Tony Johnson wrote Midas, a graphical browser for Stanford physicists. Huge advantageMidas was that it could display postscript format documents, loved by physicists for being able to accurately reproduce scientific formulas.

“With these key benefits, the web has been actively used in the physical community,” concluded the 2001 US Department of Energy evaluation of the SLAC’s progress.

Meanwhile, at CERN, Pellow and Robert Kayau launched their first Macintosh web browser. Gillis and Kayau describe the development of Samba.

For Pell, progress in launching the Samba project was slow because every few links the browser crashed and no one could understand why. “The Mac browser was full of mistakes,” Tim Berners-Lee said sadly in a 92-year-old newsletter. “I give a T-shirt with the inscription W3 to someone who can fix it!” He announced. The shirt went to John Streets from Fermilab, who tracked the error, which allowed Nicola Pellow to continue developing a working version of Samba.

Samba “was an attempt to port the design of the first browser I wrote on a NeXT machine to the Mac platform,” adds Berners-Lee, “but they didn’t have time to finish it until the NCSA released the version of Mosaic for Mac that overshadowed it.”

Samba

Mosaic

Mosaic was "the spark that ignited the explosive growth of the web in 1993," explain historians Gillis and Kayau. But it could not have been developed without its predecessors, and without the NCSA offices at the University of Illinois, equipped with the best machines with UNIX. The NCSA also had Dr. Ping Fu, a computer graphics doctor and wizard who worked on morphing effects for the movie Terminator 2. And he recently hired an assistant named Mark Andrissen.

“What about writing a browser GUI?” - Fu suggested to his new assistant. “What is a browser?” Asked Andrissen. But a few days later, one of the NCSA employees, Dave Thompson, made a presentation of the early browser of Nicola Pellow and the ViolaWWW browser from Pay Wei. And just before the presentations, Tony Johnson released the first version of Midas.

The latest program hit Andrissen. “Amazing! Fantasy! Unbelievable! Impressive, damn it! ” He wrote to Johnson. Andrissen then got NCSA's UNIX expert, Eric Binu, to help write his own browser for X.

Mosaic had many new features for the web built in, such as video support, sound, forms, bookmarks, and history. “And the amazing thing was that, unlike all early browsers for X, everything was contained in a single file,” explain Gillis and Kayau:

The installation process was simple - you just had to download it and run it. Later, Mosaic became famous for introducing a tagthat allowed for the first time to embed images directly in the text, instead of appearing in a separate window, as in Tim's first browser for NeXT. This allowed people to make web pages more like familiar print media; Not all innovators liked this idea, but definitely made Mosaic famous.

“That, in my opinion, Mark managed very well,” Tim Berners-Lee wrote later, “to make a very simple installation, and support with error correction by email, at any time of the day or night. It was possible to send him an error message, and after a couple of hours he would send you a correction. ”

The most important breakthrough of Mosaic, from today's point of view, was its cross-platform. “By the authority that no one has endowed me with, in principle, I declare X-Mosaic to be released,” Andrissen proudly wrote in the www-talk group on January 23, 1993. Alex Totik released his Mac version a few months later. The PC version appeared by the works of Chris Wilson and John Mittelhauser.

The Mosaic browser was based on Viola and Midas, as noted at the computer museum exhibit. And he used the library from CERN. “But, unlike the others, it was reliable, even non-professionals could install it, and soon he added support for color graphics in pages, rather than in separate windows.”

Mosaic Browser Available for X Windows, Mac, and Microsoft Windows

Guy from japan

But Mosaic was not the only innovative product that appeared at that time. Kansas University student Lou Montulli has adapted his campus’s hypertext information browser for the Internet and the web. It started in March 1993. “Lynx has quickly become a favorite browser for character-based terminals without graphics, and is still in use today,” explains historian Stuart.

And at Born School of Law, Cornell University, Tom Bruce wrote a web application for the PC, "because it was these computers that lawyers used to use," said Gillis and Kayau. Bruce published his browser, Cello, on June 8, 1993, "and soon it was downloaded 500 times a day."

Cello

Six months later, Andrissen was in Mountain View, California. His team planned to release Mosaic Netscape on October 13, 1994. He, Totik and Mittelhauser excitedly uploaded the application to an FTP server. The last developer recalls this moment. “Five minutes passed, and we all sat there. Nothing happened. And suddenly the first download happened. This was a guy from Japan. We vowed to send him a T-shirt! ”

This complex story reminds us that no innovation is created by a single person. The web browser came into our life thanks to visionaries from all over the world, people who often did not quite clearly understand what they were doing, but motivated by curiosity, practical considerations or even the desire to play. Their individual sparks of genius supported the whole process. Like Tim Berners-Lee’s persistence in the fact that the project should remain joint, and, most importantly, open.

“The early days of the web were very limited in resources, ” he wrote . “So much had to be done, to maintain such a weak flame.”