Leak of 809 million email addresses of Verifications.io service due to publicly open MongoDB

- Transfer

Translator's note - the reason for the translation of the article was the receipt of a Have I Been Pwned notification that my data was in this leak.

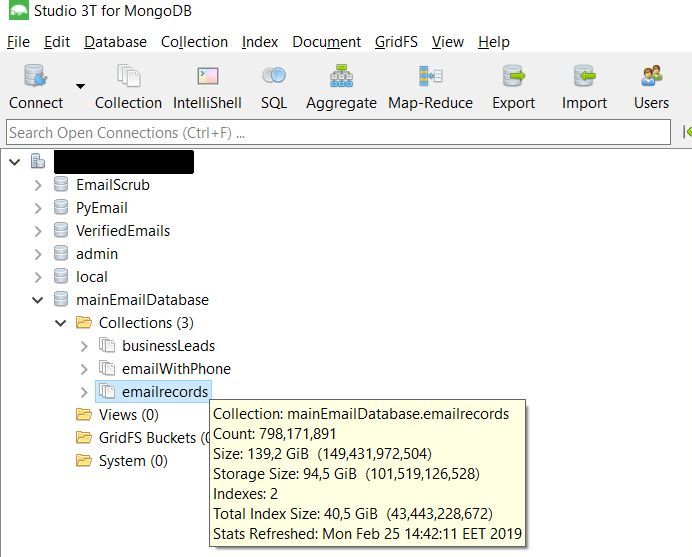

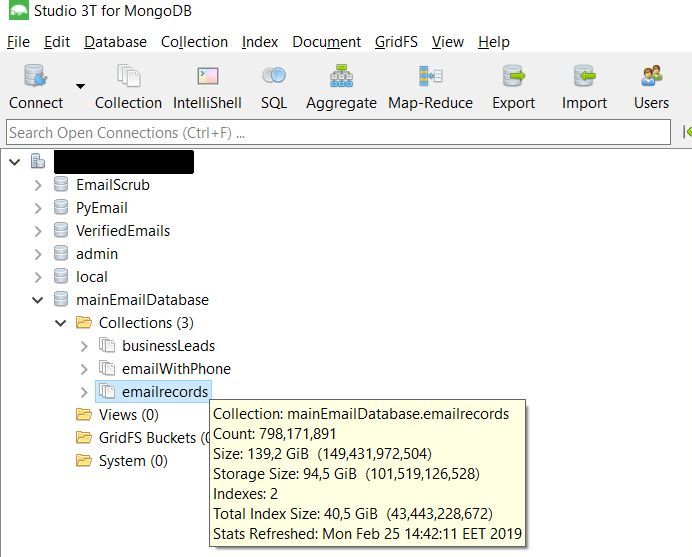

Security researchers Bob Diachenko and Vinny Troia discovered an insecure MongoDB database last week.containing 150 gigabytes of clear-text marketing information, including 763 million unique email addresses. The find is not only huge, but also unusual. It contains data on individual customers, as well as “business information”, such as data on employees and income of various companies. This diversity can be attributed to the source of information: a database owned by Verification.io to “verify” email addresses. The base was disconnected the same day when the researcher informed the company about it.

Although you've probably never heard of them, such companies play a crucial role in the e-marketing industry. They do not send marketing emails on their behalf and do not conduct automated mailings. Instead, they check the customer list to ensure that the email addresses in it are valid and not returned with an error. But a complete check that the email address is working includes sending a message to this address and confirming that it was delivered - essentially sending spam to people. This means avoiding blocking ISPs and platforms such as Gmail. (There are less crude ways to verify email addresses, but they have a trade-off in false positives.) Major email service providers often outsource this work.

“Companies have email lists and want to start mailing to them, but they’re not sure how reliable they are,” said Troia, founder of Night Lion Security. “So they go to a company that essentially sends spam.” Troia suggests that the database can be so large and diverse because it contains all the data from Verification.io clients. WIRED could not contact the company or CEO Vlad Strelkov for several days. On Monday, the Verification.io website turned off and has not been restored since. ( copy in the Internet archive approx. transl. )

In total, 809 million entries in the Verification.io database include standard information such as names, email addresses, phone numbers, and physical addresses. But many also include information such as gender, date of birth, mortgage size, interest rate, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram accounts associated with email addresses, as well as characteristics of people's credit rating (for example, average, above average, etc.) .d.). Meanwhile, other entries in the database appear to be related to B2B sales, including company names, annual revenue figures, fax numbers, company websites and industry identifiers for company classification (“SIC” and “NAIC” codes).

The data does not contain social security numbers or credit card numbers, and the only passwords in the database are for Verification.io's own infrastructure. In general, most of the data is publicly available from various sources, but when criminals can get a lot of aggregated data into their hands, it will be much easier for them to launch new fraud schemes or expand the target database.

In an open database, researchers also found some of Verification.io's internal tools, such as test email accounts, hundreds of SMTP servers (sending emails), text emails, anti-spam infrastructure, keywords to avoid, and IP addresses for blacklisting. Diachenko assumes that Verification.io clients download an Excel spreadsheet containing the email addresses to verify, and then Verification.io runs its tests and returns lists of work addresses and those that answered with an error. It is possible, given the fragmentation of the data and the evidence that they were imported from many different Excel files, that Verification.io also retained some or all of the data received from clients after checking the email addresses.

Researchers checked sample data with companies listed as Verification.io customers. Troia says its own information has appeared in the database. WIRED spoke with the owner of an email marketing company. He confirmed the accuracy of the data. WIRED also checked four people, but did not find them on the list. Diachenko and Troia also note that they have no way of knowing if anyone found Verification.io data when it was publicly available. “I have no idea if anyone else has access to this other than us,” Troia says. “But it was definitely available for everyone to download.”

Security researcher Troy Hunt adds Verification.io data to HaveIBeenPwned, which helps people check if their data has been compromised as a result of leaks. He said that 35% of the 763 million email addresses are new to the HaveIBeenPwned database. The Verification.io dump is also the second largest ever added to HaveIBeenPwned by the number of email addresses after 773 million, known as Collection # 1, that were added earlier this year. Hunt says some of his own information is included in the Verification.io database.

“The main conclusion for me is that this is just another case where someone has my data and hundreds of millions of other people's data, and I absolutely don’t know how they got it,” says Hunt. “I have never heard of a company so far, and I certainly can’t remember if they have consent to use my data. Of course, it’s quite possible that some of the terms and conditions of service say that they can use my data in this way, but this does not quite meet my expectations regarding how my data should be used. ”

The fragmented nature of the presented data Verification.io speaks of the chaotic state of the data industry as a whole. Personal information is transferred to huge corporations such as Facebook, bought and sold by dubious marketers, or stolen from data giants and is doomed to endlessly spread in the purgatory of criminal forums. It becomes more difficult for users to control who has their data and where they are located. As Hunt says: “Unfortunately, this is just another day on the Internet.”

Note of the translator - this is my first translation on Habré, I ask to inform about errors and inaccuracies in personal messages.

Security researchers Bob Diachenko and Vinny Troia discovered an insecure MongoDB database last week.containing 150 gigabytes of clear-text marketing information, including 763 million unique email addresses. The find is not only huge, but also unusual. It contains data on individual customers, as well as “business information”, such as data on employees and income of various companies. This diversity can be attributed to the source of information: a database owned by Verification.io to “verify” email addresses. The base was disconnected the same day when the researcher informed the company about it.

Although you've probably never heard of them, such companies play a crucial role in the e-marketing industry. They do not send marketing emails on their behalf and do not conduct automated mailings. Instead, they check the customer list to ensure that the email addresses in it are valid and not returned with an error. But a complete check that the email address is working includes sending a message to this address and confirming that it was delivered - essentially sending spam to people. This means avoiding blocking ISPs and platforms such as Gmail. (There are less crude ways to verify email addresses, but they have a trade-off in false positives.) Major email service providers often outsource this work.

“Companies have email lists and want to start mailing to them, but they’re not sure how reliable they are,” said Troia, founder of Night Lion Security. “So they go to a company that essentially sends spam.” Troia suggests that the database can be so large and diverse because it contains all the data from Verification.io clients. WIRED could not contact the company or CEO Vlad Strelkov for several days. On Monday, the Verification.io website turned off and has not been restored since. ( copy in the Internet archive approx. transl. )

In total, 809 million entries in the Verification.io database include standard information such as names, email addresses, phone numbers, and physical addresses. But many also include information such as gender, date of birth, mortgage size, interest rate, Facebook, LinkedIn and Instagram accounts associated with email addresses, as well as characteristics of people's credit rating (for example, average, above average, etc.) .d.). Meanwhile, other entries in the database appear to be related to B2B sales, including company names, annual revenue figures, fax numbers, company websites and industry identifiers for company classification (“SIC” and “NAIC” codes).

The data does not contain social security numbers or credit card numbers, and the only passwords in the database are for Verification.io's own infrastructure. In general, most of the data is publicly available from various sources, but when criminals can get a lot of aggregated data into their hands, it will be much easier for them to launch new fraud schemes or expand the target database.

In an open database, researchers also found some of Verification.io's internal tools, such as test email accounts, hundreds of SMTP servers (sending emails), text emails, anti-spam infrastructure, keywords to avoid, and IP addresses for blacklisting. Diachenko assumes that Verification.io clients download an Excel spreadsheet containing the email addresses to verify, and then Verification.io runs its tests and returns lists of work addresses and those that answered with an error. It is possible, given the fragmentation of the data and the evidence that they were imported from many different Excel files, that Verification.io also retained some or all of the data received from clients after checking the email addresses.

Researchers checked sample data with companies listed as Verification.io customers. Troia says its own information has appeared in the database. WIRED spoke with the owner of an email marketing company. He confirmed the accuracy of the data. WIRED also checked four people, but did not find them on the list. Diachenko and Troia also note that they have no way of knowing if anyone found Verification.io data when it was publicly available. “I have no idea if anyone else has access to this other than us,” Troia says. “But it was definitely available for everyone to download.”

Security researcher Troy Hunt adds Verification.io data to HaveIBeenPwned, which helps people check if their data has been compromised as a result of leaks. He said that 35% of the 763 million email addresses are new to the HaveIBeenPwned database. The Verification.io dump is also the second largest ever added to HaveIBeenPwned by the number of email addresses after 773 million, known as Collection # 1, that were added earlier this year. Hunt says some of his own information is included in the Verification.io database.

“The main conclusion for me is that this is just another case where someone has my data and hundreds of millions of other people's data, and I absolutely don’t know how they got it,” says Hunt. “I have never heard of a company so far, and I certainly can’t remember if they have consent to use my data. Of course, it’s quite possible that some of the terms and conditions of service say that they can use my data in this way, but this does not quite meet my expectations regarding how my data should be used. ”

The fragmented nature of the presented data Verification.io speaks of the chaotic state of the data industry as a whole. Personal information is transferred to huge corporations such as Facebook, bought and sold by dubious marketers, or stolen from data giants and is doomed to endlessly spread in the purgatory of criminal forums. It becomes more difficult for users to control who has their data and where they are located. As Hunt says: “Unfortunately, this is just another day on the Internet.”

Note of the translator - this is my first translation on Habré, I ask to inform about errors and inaccuracies in personal messages.