When we get back to deep space exploration

Launch of the New Horizons launch vehicle, Cape Canaveral, 2006.

In December, the Washington Post published an article about a breakthrough for the space industry: the United States received 50 grams of plutonium-238, an unarmed isotope, and potential fuel for deep spacecraft. On such flew the Cassini spacecraft and the Voyagers line. The last device on plutonium was NASA's interplanetary station. New Horizons: in the fall of 2015, she took a bunch of pictures of the surface of Pluto , the Internet went crazy over them.

The principle of operation of such devices is simple: engineers put on board a generator (RTG), inside - plutonium dioxide, a radioactive isotope with a half-life of 88 years, such a “perpetual battery”. It saves the apparatus from the need to constantly be in the light, as if it were fed by solar panels, and does not die, only flew away from the Sun. But the panels are short-lived: they are fragile and quickly degrade (what is 20 years for an endless space, gentlemen?).

Over 60 years of RTG refinements, engineers sorted out a bunch of isotopes, increased protection levels and came up with fabulous technology: if you send research devices into space with ends, there’s no need to even think about plutonium burial. Other engineers began developing generators with increased energy efficiency. There were bright prospects for the study of space.

And plutonium ended: in 1985, the world got the idea to limit the nuclear potential of the States and the USSR, the only plutonium producers. U.S. non-weapons-grade plutonium production facilities were tied to weapons-grade plutonium, so we had to collapse the entire tent. And the reserves of the Cold War era were dissolving faster than our governments had time to come to their senses: in 1988, the United States closed the production of plutonium when it dismissed the Department of Energy. In 1992, the U.S. Department of Energy began purchasing plutonium in Russia - the contract allowed NASA to send Curiosity's science lab to Mars. The US Department of Energy has 35 kilograms of old plutonium in its hands: its energy output from the eighties has fallen to 80 percent, and continues to fall.

In 2001, NASA sponsored the U.S. State Research Council to convene a committee to review the status of plutonium-238 production. Well, then everyone understood:

- that plutonium-238 is not in nature

- that he is not weapons

- that the Department of Energy dismissed in vain

- that the States are not able to create RTGs for subsequent missions.

In 2013, after 12 years, the Tennessee science lab gave the go-ahead to launch reactors, funded and added the capacities of two other Los Alamos and Idaho laboratories to speed up the process. The Department of Energy set a target of 1.5–2 kilograms of plutonium per year. Optimism of the highest category. For 3 years they produced 50 grams, which is 50 grams more than Russia over the same period.

What does Russia do

Either nothing, or is silent and works quietly and slowly. There are rumors in the press, but the close observer has nothing to catch his eye on.

A year ago, I defended my diploma on projects that would return the RTG to space. And I would continue the topic in my dissertation, I would write at the enterprise with experts in shipbuilding and veterans of the atomic industry. Similar in Russia they could still study at the Krasnaya Zvezda NPO: before, they made nuclear power plants for use in space - BUK, TOPAZ, that's all . He asked to go there, but they refused me: they didn’t want to hang up a security stamp for the dissertation and to collect a special commission — many problems for the sake of one student. Pure negligence.

When we get enough fuel to fly

After 10 years, the minimum, if we work hard together. Today, NASA can mix new plutonium with old in a 1: 2 ratio. Oakridge Laboratory in Tennessee promises to make 1.5 kilograms of plutonium by the beginning of the next decade. Conventionally, in 2025 we will have 5 kilograms of usable fuel - the old plutonium will become even more unusable, and the proportions will be replaced. The result will be enough for one mission, even taking into account new types of generators, with an increase in efficiency of 4 times.

Of the old fuel, 25 kilograms will go on an international mission to the satellites of Jupiter in 2020. Roscosmos will also take part: RIA wrote in 2013 that they will have 2 RTGs, but there is no one to confirm.

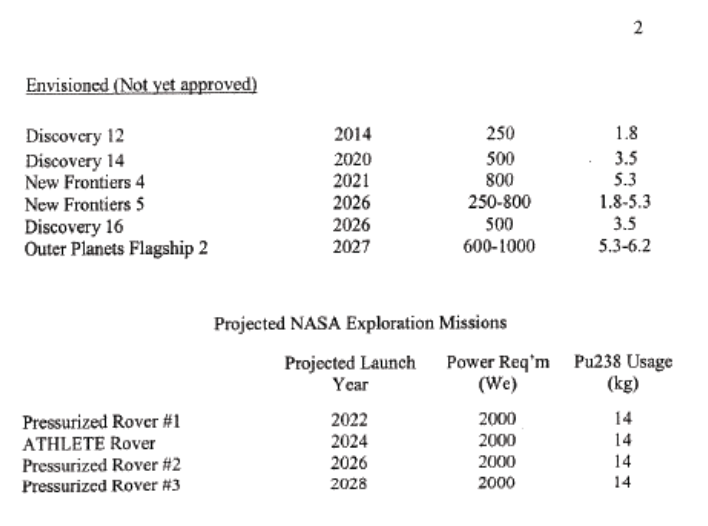

The reason for my sadness is a letter of inquiry to the US Department of Energy from the NASA administration dated April 29, 2008

I look at the 2008 launch schedule and am sad: in addition to the 8 canceled projects, NASA will have to postpone the same amount. Exploration of deep space - and 99% of the solar system - will continue no earlier than the mid-twenties. In the meantime, we will live in Wonderland: to stay in place, we will have to run forward very, very quickly.