US Computer Heritage: Mark I

American scientist Howard Aiken set about developing a machine that was based on the bold ideas of the 19th and 20th century technologies. With the support of the US Navy command and financial and technical support from IBM, Aiken created the first American computer - Mark I. Simple electromechanical relays were used as switching devices in Aiken's car; Instructions for data processing programs were recorded on punched tape. Data is entered into the machine in the form of decimal numbers encoded on IBM punched cards.

American scientist Howard Hathaway Aiken (born Howard Hathaway Aiken, 1900 - 1973) was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, USA. This man possessed an extremely broad horizons and was interested in various scientific areas, which included physics, mathematics, and many natural sciences. Aiken graduated from the Indianapolis Military Engineering School and earned a bachelor's degree. At the University of Wisconsin, he successfully defended his diploma in Electrical Engineering. But Aiken was not going to stop halfway and continued his studies by entering the magistracy of the University of Chicago in 1939. And soon he moved to the famous Harvard to complete his studies there. Aiken received his Ph.D. in physics in 1939 and began work on a dissertation, devoted to methods for solving nonlinear differential equations. Around that time, he had the idea to create an automatic computing device that could eliminate the need to carry out tedious mathematical calculations. In the process of thinking and developing the design of several simple calculators, each of which could solve a specific problem of narrow specialization, Aiken came to the conclusion that it was necessary to create a universal device capable of performing any mathematical calculations. Burning this idea, he enlisted the support of Harvard University and one of the largest American commercial companies of those times - International Business Machines (IBM). The scientist began the practical implementation of his ideas. As an IBM Engineer,

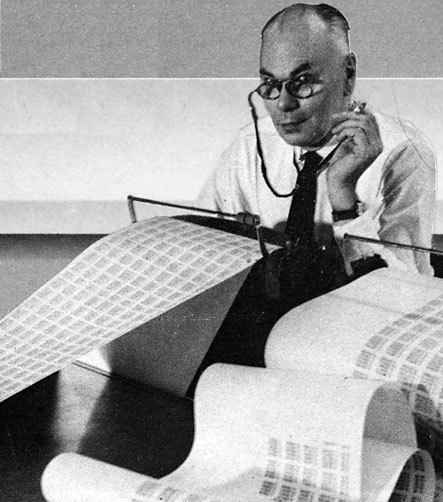

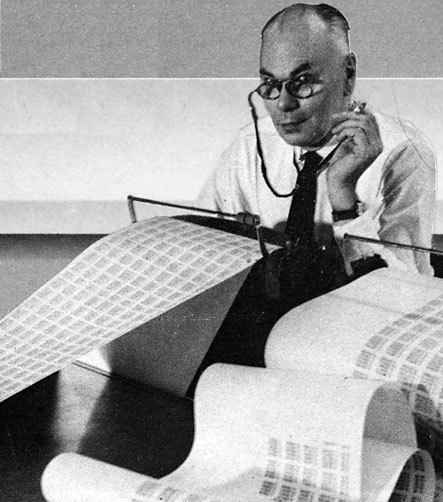

Howard Aiken observes the work of Mark I (1944)

Charles Babbage's difference machine inspired the work on Aiken's computer. The description of this analytical machine, which was left from Babbage himself, turned out to be quite thorough and complete.

As Aiken later stated:

Babbage difference machine

After fruitful work, Aiken managed to translate his idea into reality. Initially, the project was called “Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator” (ASCC), that is, “computing device controlled by automatic sequences.” But by ear, the first American computer entrenched under the name "Harvard Mark I".

Implementation of the project

The process of creating the Mark I machine was calm, smooth and without excesses. In early 1943, the device successfully passed the first tests and was transferred to Harvard University. But the relationship between the creator of the device and its sponsor was far from so harmonious. Mark I caused Aiken to disagree with IBM CEO Thomas Watson.

Thomas Watson - IBM Chairman

These two people had a strong, but incredibly stubborn character. They both loved to do everything exclusively in their own way. First of all, their opinions diverged due to the appearance of the car. Mark I reached a length of almost 17 meters, and in height exceeded 2.5 meters. It contained about 750,000 parts, which were connected by wires with a total length of approximately 800 km. One can imagine how a monster such an engine appeared to be an engineer. Aiken wanted to leave Mark's internal contents open so that, if necessary, specialists could see the composition and operation of the device. Watson, as the head of the company and businessman, wanted to make Mark I the most attractive to customers. Therefore, he actively insisted that the car be enclosed in a case made of glass and shiny stainless steel. In this argument, Watson won. Actually, all subsequent disagreements were also resolved in his favor. IBM had the last word, because the company financed the development of the machine and could dictate its own conditions. But Aiken was able to "recoup" at the presentation of Mark I before the press and the public in August 1944. Talking about the device and the development process, he barely mentioned IBM's contribution to the creation of the computer. And about Thomas Watson did not say a word. Naturally, this infuriated the head of the company. he barely mentioned IBM's contribution to the creation of the computer. And about Thomas Watson did not say a word. Naturally, this infuriated the head of the company. he barely mentioned IBM's contribution to the creation of the computer. And about Thomas Watson did not say a word. Naturally, this infuriated the head of the company.

Watson's indignation knew no bounds that he was not even afraid of harsh remarks towards Aiken in front of the media:

His son and successor Watson Jr. said later that if Aiken and Watson Sr. lived in a different century, they would certainly have fought in a duel and killed each other.

Military Service

Shortly afterwards, Watson temporarily handed over Mark I to the U.S. Navy. There, the machine was used to perform complex ballistic calculations, which Aiken himself directed. Mark I could work with numbers up to 23 digits long. It took 0.3 seconds to add and subtract, and about 3 seconds to multiply. This speed was unusual and even amazing, although it was only slightly superior to the performance originally planned by Babbage. Mark I spent one day calculus, which previously took up to six months.

Aiken with scientist Grace Hoper and members of the US Navy team serving Mark I

The computer of Mark I looked very impressive. Watson's design idea was implemented properly and played a role - clear glass and sparkling stainless steel attracted attention from both the press and technical experts. In addition, the car was serviced by naval officers, maintaining its exemplary cleanliness and order. Serious, businesslike, they walked around Mark I saluting each other. As Harvard scientists recalled, it seemed as though officers were driving a machine while standing at attention. That's just the noise of the computer slightly spoiled the idyll - the on and off relays (3304 pcs.) Clicked loudly, controlling the rotation of the rollers and gears.

Mark I sailor

A quarrel with IBM in the person of its director did not prevent Aiken from continuing to work on creating new computers. And already in 1947 he graduated from Harvard Mark II, followed by Harvard Mark III (1949) and Harvard Mark IV (1952). The Mark III computer already used separate electronic components, and the Mark IV was a fully electronic device. The machines had memory based on magnetic drums. In addition, “Mark IV” used another kind of computer memory based on the use of magnetic cores.

Because Mark I was invaluable, it’s not surprising that the U.S. Department of Defense was responsible for financing further development of computers. American experts in the field of cybernetics are very interested in Aiken's projects. Actually, Mark II was built by a scientist specifically for the Navy, he became the first multitask computing device on the planet: the parallel adders provided for in his design made it possible to simultaneously perform several mathematical operations and transfer the result from one machine module to another.

The first computers, such as Mark I, were based on electromechanical switches, widely used at that time in telephone communication technology. When the switch was in the open state, the circuit was de-energized. But if a low voltage current was applied to the winding of the iron core (shown in red in the diagram), then a magnetic field was created in the core, attracting one end of the lever rotating on the hinge. At this moment, its other end squeezed the contacts: the circuit closed and an electric current began to pass through it (shown in green in the diagram).

action scheme of electromechanical switches

The numbers processed by the machine were stored in special registers implemented in the form of metal gears, which were set in motion by a special mechanism. Each register included 24 wheels, of which 23 were used to represent the digits of the number itself, and the 24th was its sign. In addition, each register had a device that allowed you to store tens of values and transfer the result of the calculations to another register. In total, the architecture of Mark I consisted of 72 registers for processing digital values and 60 additional registers for storing mathematical constants - in them, using a system of switches, constants that were constant during the calculation were manually recorded. As part of Mark I, there was a basic mathematical unit, and also there were several separate modules designed to perform operations of multiplication, division, calculating the power of a number, the sine value, and calculating the logarithm. The operator panel was a panel containing 420 mechanical switches, not counting several control panels that allowed the operator to control the operating modes of the machine. The device consumed about 160 kilowatts of power during its operation.

kind of registers mark I

The real technological innovation was the device proposed by Aiken, which was intended for programming the sequence of operations performed by the calculating machine. As an information carrier, the inventor used a dielectric celluloid punched tape, in which holes were arranged in 24 parallel rows. The data obtained was divided into two categories: operational teams that described what the machine should do at a given time, and computational teams that controlled the mathematical operations themselves. A punched tape containing a description of the sequence of operations could be stored separately from the mathematical device itself and reused as needed. Thus, the principle of an independently stored program was first implemented in a Mark I computer. Data from the punched tape was read by special contact brushes, which, when they got into the hole, closed the electric circuit. After the operation, the punched tape was shifted by one position and substituted a new row of holes under the brushes.

Grace Hoper (1906-1992).

It is also curious that the modern term “bug” (from the English “bug” - “bug”), meaning a mistake or malfunction in the program, in those days had a literal meaning. In the process, the computers Mark I and Mark II were heated quite strongly, so that some of their nodes emitted a dim glow. All kinds of insects flew into the light and heat - midges, moths, small butterflies, etc. ... They climbed inside and often caused short circuits of electrical circuits. According to one version, the term “bug” was introduced by Grace Hopper, an employee of the US Navy's Coastal Service Data Center. She worked in a team of Mark II. Later, this woman became a world-famous computer analyst and programmer, and in addition she received the honorary title of Rear Admiral of the Navy for her services.

She is credited with the appearance of another term “debugging”, which refers to the process of correcting errors made by a programmer while writing program code.

Grace Hopper described this episode as follows:

About 16 years, Mark I worked in the mathematical field at Harvard University. He helped to compile mathematical tables and solved a wide variety of problems, from creating economic models to constructing electronic circuits of computers. But his success did not fully meet Watson's expectations. Computer development methods were inferior to the more promising methods of German and English inventors. In fact, Mark I was outdated before it was built.

American scientist Howard Hathaway Aiken (born Howard Hathaway Aiken, 1900 - 1973) was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, USA. This man possessed an extremely broad horizons and was interested in various scientific areas, which included physics, mathematics, and many natural sciences. Aiken graduated from the Indianapolis Military Engineering School and earned a bachelor's degree. At the University of Wisconsin, he successfully defended his diploma in Electrical Engineering. But Aiken was not going to stop halfway and continued his studies by entering the magistracy of the University of Chicago in 1939. And soon he moved to the famous Harvard to complete his studies there. Aiken received his Ph.D. in physics in 1939 and began work on a dissertation, devoted to methods for solving nonlinear differential equations. Around that time, he had the idea to create an automatic computing device that could eliminate the need to carry out tedious mathematical calculations. In the process of thinking and developing the design of several simple calculators, each of which could solve a specific problem of narrow specialization, Aiken came to the conclusion that it was necessary to create a universal device capable of performing any mathematical calculations. Burning this idea, he enlisted the support of Harvard University and one of the largest American commercial companies of those times - International Business Machines (IBM). The scientist began the practical implementation of his ideas. As an IBM Engineer,

Howard Aiken observes the work of Mark I (1944)

Charles Babbage's difference machine inspired the work on Aiken's computer. The description of this analytical machine, which was left from Babbage himself, turned out to be quite thorough and complete.

As Aiken later stated:

If Charles Babbage lived 75 years later, I would definitely be unemployed ...

Babbage difference machine

After fruitful work, Aiken managed to translate his idea into reality. Initially, the project was called “Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator” (ASCC), that is, “computing device controlled by automatic sequences.” But by ear, the first American computer entrenched under the name "Harvard Mark I".

Implementation of the project

The process of creating the Mark I machine was calm, smooth and without excesses. In early 1943, the device successfully passed the first tests and was transferred to Harvard University. But the relationship between the creator of the device and its sponsor was far from so harmonious. Mark I caused Aiken to disagree with IBM CEO Thomas Watson.

Thomas Watson - IBM Chairman

These two people had a strong, but incredibly stubborn character. They both loved to do everything exclusively in their own way. First of all, their opinions diverged due to the appearance of the car. Mark I reached a length of almost 17 meters, and in height exceeded 2.5 meters. It contained about 750,000 parts, which were connected by wires with a total length of approximately 800 km. One can imagine how a monster such an engine appeared to be an engineer. Aiken wanted to leave Mark's internal contents open so that, if necessary, specialists could see the composition and operation of the device. Watson, as the head of the company and businessman, wanted to make Mark I the most attractive to customers. Therefore, he actively insisted that the car be enclosed in a case made of glass and shiny stainless steel. In this argument, Watson won. Actually, all subsequent disagreements were also resolved in his favor. IBM had the last word, because the company financed the development of the machine and could dictate its own conditions. But Aiken was able to "recoup" at the presentation of Mark I before the press and the public in August 1944. Talking about the device and the development process, he barely mentioned IBM's contribution to the creation of the computer. And about Thomas Watson did not say a word. Naturally, this infuriated the head of the company. he barely mentioned IBM's contribution to the creation of the computer. And about Thomas Watson did not say a word. Naturally, this infuriated the head of the company. he barely mentioned IBM's contribution to the creation of the computer. And about Thomas Watson did not say a word. Naturally, this infuriated the head of the company.

Watson's indignation knew no bounds that he was not even afraid of harsh remarks towards Aiken in front of the media:

You dare not be so dismissive of IBM! For me, this company means no less than for you, Harvard graduates, your university!

His son and successor Watson Jr. said later that if Aiken and Watson Sr. lived in a different century, they would certainly have fought in a duel and killed each other.

Military Service

Shortly afterwards, Watson temporarily handed over Mark I to the U.S. Navy. There, the machine was used to perform complex ballistic calculations, which Aiken himself directed. Mark I could work with numbers up to 23 digits long. It took 0.3 seconds to add and subtract, and about 3 seconds to multiply. This speed was unusual and even amazing, although it was only slightly superior to the performance originally planned by Babbage. Mark I spent one day calculus, which previously took up to six months.

Aiken with scientist Grace Hoper and members of the US Navy team serving Mark I

The computer of Mark I looked very impressive. Watson's design idea was implemented properly and played a role - clear glass and sparkling stainless steel attracted attention from both the press and technical experts. In addition, the car was serviced by naval officers, maintaining its exemplary cleanliness and order. Serious, businesslike, they walked around Mark I saluting each other. As Harvard scientists recalled, it seemed as though officers were driving a machine while standing at attention. That's just the noise of the computer slightly spoiled the idyll - the on and off relays (3304 pcs.) Clicked loudly, controlling the rotation of the rollers and gears.

Mark I sailor

A quarrel with IBM in the person of its director did not prevent Aiken from continuing to work on creating new computers. And already in 1947 he graduated from Harvard Mark II, followed by Harvard Mark III (1949) and Harvard Mark IV (1952). The Mark III computer already used separate electronic components, and the Mark IV was a fully electronic device. The machines had memory based on magnetic drums. In addition, “Mark IV” used another kind of computer memory based on the use of magnetic cores.

Because Mark I was invaluable, it’s not surprising that the U.S. Department of Defense was responsible for financing further development of computers. American experts in the field of cybernetics are very interested in Aiken's projects. Actually, Mark II was built by a scientist specifically for the Navy, he became the first multitask computing device on the planet: the parallel adders provided for in his design made it possible to simultaneously perform several mathematical operations and transfer the result from one machine module to another.

The first computers, such as Mark I, were based on electromechanical switches, widely used at that time in telephone communication technology. When the switch was in the open state, the circuit was de-energized. But if a low voltage current was applied to the winding of the iron core (shown in red in the diagram), then a magnetic field was created in the core, attracting one end of the lever rotating on the hinge. At this moment, its other end squeezed the contacts: the circuit closed and an electric current began to pass through it (shown in green in the diagram).

action scheme of electromechanical switches

The numbers processed by the machine were stored in special registers implemented in the form of metal gears, which were set in motion by a special mechanism. Each register included 24 wheels, of which 23 were used to represent the digits of the number itself, and the 24th was its sign. In addition, each register had a device that allowed you to store tens of values and transfer the result of the calculations to another register. In total, the architecture of Mark I consisted of 72 registers for processing digital values and 60 additional registers for storing mathematical constants - in them, using a system of switches, constants that were constant during the calculation were manually recorded. As part of Mark I, there was a basic mathematical unit, and also there were several separate modules designed to perform operations of multiplication, division, calculating the power of a number, the sine value, and calculating the logarithm. The operator panel was a panel containing 420 mechanical switches, not counting several control panels that allowed the operator to control the operating modes of the machine. The device consumed about 160 kilowatts of power during its operation.

kind of registers mark I

The real technological innovation was the device proposed by Aiken, which was intended for programming the sequence of operations performed by the calculating machine. As an information carrier, the inventor used a dielectric celluloid punched tape, in which holes were arranged in 24 parallel rows. The data obtained was divided into two categories: operational teams that described what the machine should do at a given time, and computational teams that controlled the mathematical operations themselves. A punched tape containing a description of the sequence of operations could be stored separately from the mathematical device itself and reused as needed. Thus, the principle of an independently stored program was first implemented in a Mark I computer. Data from the punched tape was read by special contact brushes, which, when they got into the hole, closed the electric circuit. After the operation, the punched tape was shifted by one position and substituted a new row of holes under the brushes.

Grace Hoper (1906-1992).

It is also curious that the modern term “bug” (from the English “bug” - “bug”), meaning a mistake or malfunction in the program, in those days had a literal meaning. In the process, the computers Mark I and Mark II were heated quite strongly, so that some of their nodes emitted a dim glow. All kinds of insects flew into the light and heat - midges, moths, small butterflies, etc. ... They climbed inside and often caused short circuits of electrical circuits. According to one version, the term “bug” was introduced by Grace Hopper, an employee of the US Navy's Coastal Service Data Center. She worked in a team of Mark II. Later, this woman became a world-famous computer analyst and programmer, and in addition she received the honorary title of Rear Admiral of the Navy for her services.

She is credited with the appearance of another term “debugging”, which refers to the process of correcting errors made by a programmer while writing program code.

Grace Hopper described this episode as follows:

One of the summer days of 1945 there was unbearable heat in the laboratory, when suddenly an emergency computer shutdown occurred. When we began to deal with the problem, it turned out that the failure was caused by another moth, which shorted the contacts of one of the thousands of relays. And just at that moment an officer came to us. He asked what we were doing. We replied that we cleaned the computer of insects (debuging). This term has taken root and has since been used to denote troubleshooting in a computer, in particular in software

About 16 years, Mark I worked in the mathematical field at Harvard University. He helped to compile mathematical tables and solved a wide variety of problems, from creating economic models to constructing electronic circuits of computers. But his success did not fully meet Watson's expectations. Computer development methods were inferior to the more promising methods of German and English inventors. In fact, Mark I was outdated before it was built.