Spanish engineers have created an exeskeleton for children with muscle atrophy

Engineers from the Spanish company Marsi Bionics, together with the National Research Council of Spain, created an autonomous exoskeleton to treat and help children suffering from spinal muscular atrophy. In Spain, this disease occurs in about one in ten thousand babies. Physicians from the hospital of St. Juan de Dios also took part in the development and testing.

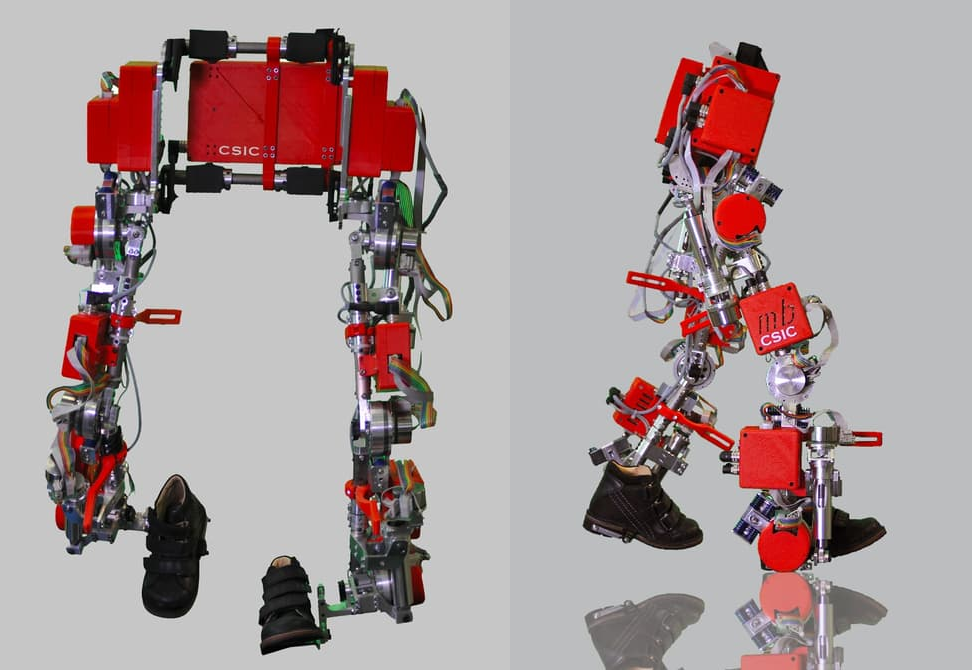

Created by engineers from aluminum and titanium, the exoskeleton weighs only 12 kilograms and has a resource of up to five hours of battery life on a single battery charge. Electric motors are installed on the “joints” of the exoskeleton, which take on part of the load and provide the child with the force necessary for movement. In total, there are five electric motors for each leg. In addition, the size of the exoskeleton can be adjusted for a specific child, which gives the product versatility.

Photo of the created exoskeleton

Spinal muscular atrophy is a hereditary disease that manifests itself in different patients at different ages. With it, there is a defeat of motor neurons and horns of the spinal cord. Children are characterized by impaired motor functions, such as crawling (and subsequently walking), head holding, and swallowing. All this interferes with the movement of the child and, as a result, its full physical development, which affects the health and life expectancy, and in the absence of treatment and the development of the disease, the patient faces complete paralysis. It is worth noting that spinal muscular atrophy does not cause mental retardation .

According to Elena Garcia, an engineer at the Center for Automation and Robotics at the University of Spain, "the main problem of exoskeletons in this context is that with the development of diseases such as spinal atrophy, over time, not only the limbs, but also the muscles of the body are affected in the patient." That is why the massive effective use of exoskeletons in muscle atrophy was difficult - in each case, its own model of device was required. The development of Spanish engineers, in terms of efforts to support the body, is able to adapt to the needs of each specific child.

Elena Garcia also adds that a lightweight model can be created for those patients whose muscle damage is not too extensive. “We could make construction easier for such people and reduce the number of electric drives,” she says.

The exoskeleton has limited construction dimensions and is suitable for use by children aged three to fourteen. It is planned to apply it not only for household adaptation of children, but also for the treatment of patients in a hospital.

With spinal muscular atrophy, the percentage of child mortality is high, but in some patients the symptoms appear much later (from 18 months and later), already at a more mature age. Most often, such patients lose the opportunity to walk in their youth, their life expectancy is not reduced, but it cannot be called comfortable. For them, the development of Spanish engineers and doctors is a chance to regain the lost opportunity to walk and again lead a full and independent life.