A swarm of satellites as a replacement for large orbital telescopes

Space telescopes are of great importance for science, they allow to obtain information that other means can not get. But their development is a very complicated and time-consuming process. If something goes wrong, all the work may be in vain. Problems with orbital telescopes arise constantly - from Hubble to James Webb.

In the latter case, the launch of the system was postponed several times, since the development team cannot launch a telescope into orbit, in which there is even the slightest inaccuracies and errors. Most likely, Webb will still be launched, but creating it is an extremely complex process. To do something more ambitious is almost an impossible task. But there is a solution.

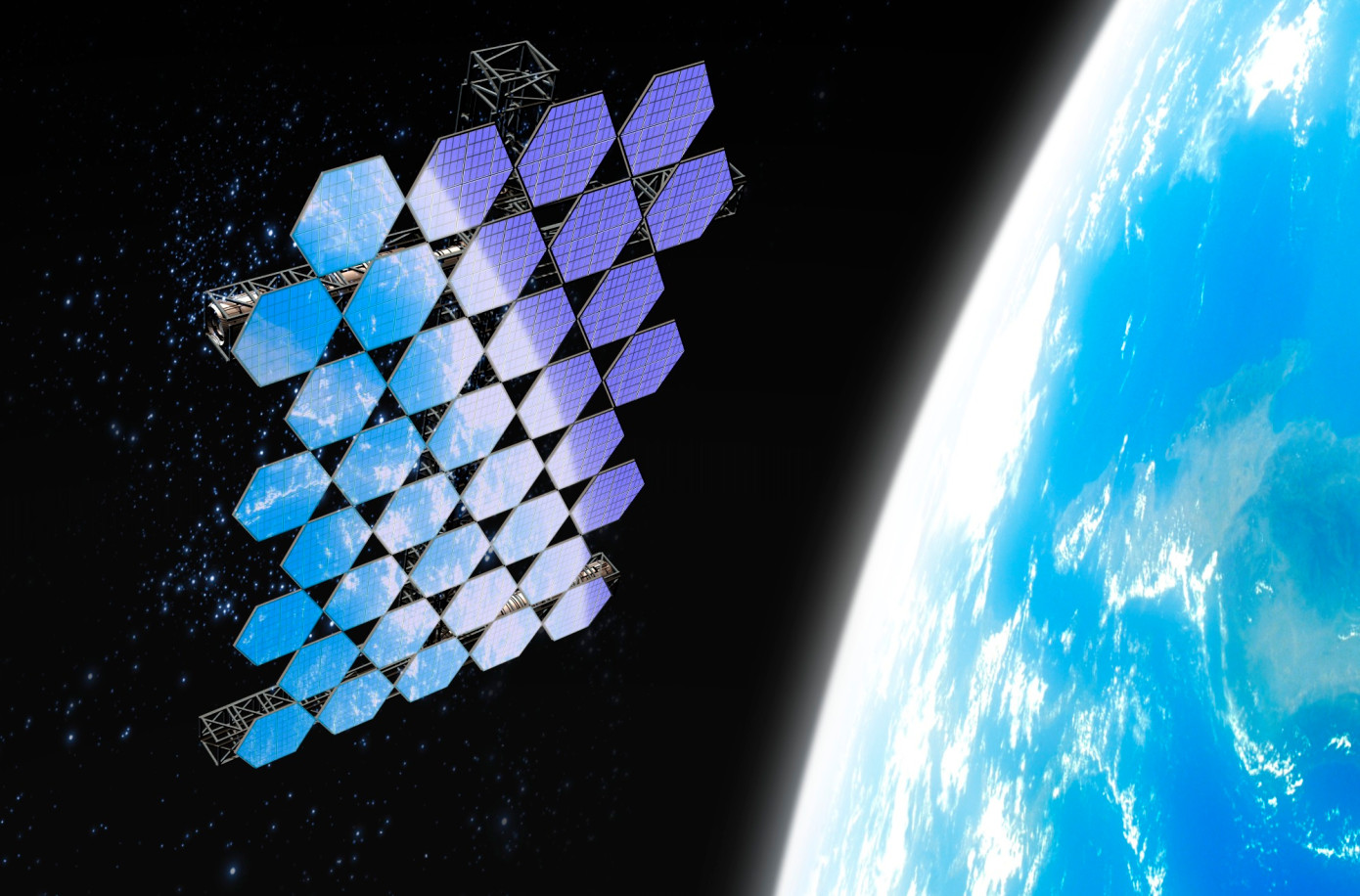

Scientists from Ben-Gurion University (Israel) propose to change the approach when creating orbiting telescopes. Perhaps these systems do not need to be made a single monolith (in the case of "James Webb" it is a monolith, albeit a composite one). Instead, you can launch a whole swarm of satellites that will receive many images. They will be processed with the help of a powerful computer, synthesizing huge high-quality images.

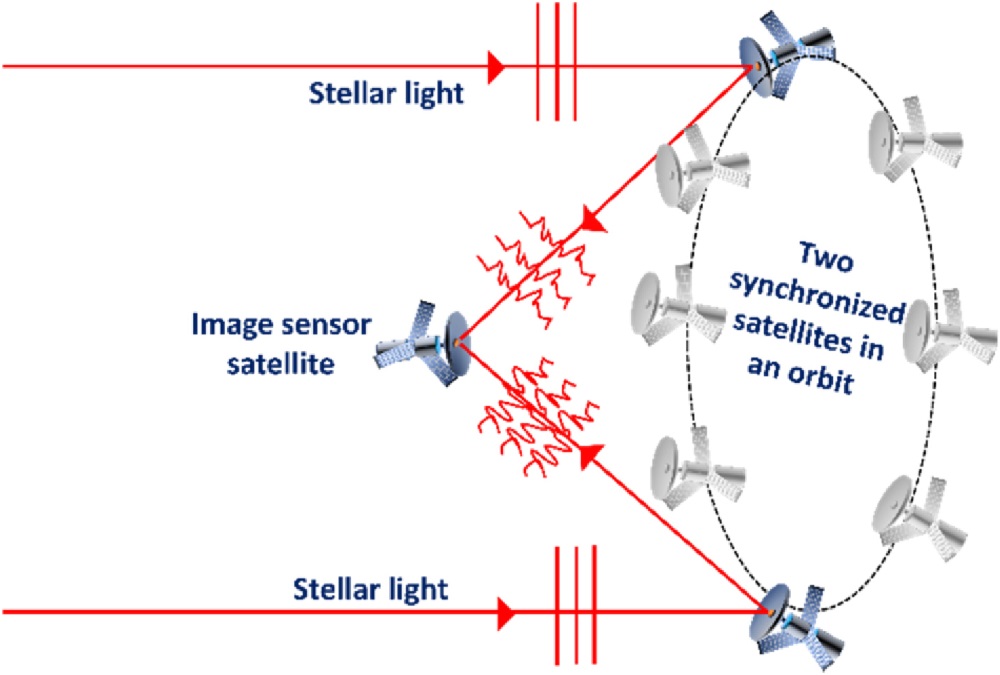

An example would be a system of three satellites. Two synchronously moving in a certain orbit, taking pictures at equal intervals of time. Further, the received information is sent to the third satellite, which unites all this. It turns out that two satellites create photographs of a synthetic aperture, and the third handles all this. As a result, the resulting images are superior in quality (or rather, they can exceed) the photographs obtained by monolithic systems.

Israeli developers claimthat supercomplex mirrors are not necessary for the operation of such a system, it is possible to do with relatively simple lenses. A system of several satellites can create images that are equal in quality to those photographs that can only be obtained with a telescope, equipped with a much larger mirror. At the same time, the failure of one satellite is not a deadly problem for the project.

A small satellite can be replaced. But if in space there are problems with a giant like “James Webb”, then, most likely, no one can fix it. In addition, the cost of creating synchronous systems from a large number of satellites is much lower than the cost of creating a monolithic orbital telescope.

True, there is one problem. The fact is that space telescopes must measure an extraordinary degree of accuracy. Outside movement in a fraction of a millimeter can negate the results of continuous work. If the system consists of several satellites, then it is somewhat more difficult to achieve accuracy than in the case of the "monolith". But still possible.

In space, telescopes are guided by "beacons", most often they are bright stars. Sometimes laser beams are used, but not too often, it is rather an exception. These methods have advantages and disadvantages, and quite a lot of them. MIT scientists believe that all this can be solved by launching special satellites into certain points in the space around the Earth, which will serve as beacons for larger systems. They will become laser pointers, forming a navigation system that can be used to solve a wide range of tasks.

Satellites will be able to provide light, the characteristics of which will not change too much over time. In addition, the satellite will transmit to the general system its own characteristics, including its position in space, so that with the help of these data it will be possible to achieve high precision measurements of the composite orbital telescope.

Both technologies are in their infancy. But if the theory turns out to be correct and everything will work in practice (it will be possible to find out only in a few years), then whole swarms of small satellites will be sent to near-earth space, where they will become observers for the “outside world”. This will be a breakthrough in modern astronomy. Of course, there are too many “ifs” here, but I would like to hope that the idea is practically realizable.