How Designers Control Luck in Games

- Transfer

On September 16, 2007, a Japanese youtuber with the nickname Computing Aesthetic uploaded a 48-second video with the loud name “ULTRA MEGA SUPER LUCKY SHOT”. The video shows a super-productive shot in the popular Peggle game, based in part on the principle of Japanese pachinko machines. In this game, the ball flies around the screen, earning points when hitting multi-colored pins that disappear almost immediately after hitting; the more hits, the more points. Although mastery is also required in Peggle — before the shot, the player must precisely aim — the game fundamentally depends on the success of the ball bounces. In the Computing Aesthetic video, the player earns a huge amount of points thanks to successful bounces between the pins. To emphasize the apparent success of the shot, the game, until the last frames of the video, plays Beethoven’s euphoric “Ode to Joy”, after which the ball falls into the hole at the bottom of the playing field and the flickering “FEVER SCORE” message appears on the screen. The description of the video, viewed almost a quarter of a million times, reads “I couldn't balieve this when it happened !!!!!!!!!” (“I can’t tell you what happened !!!”)

Shulers BC. Cheating dice, often made from animal hooves, were found in the graves. Such findings prove that even if the ancients believed that the roll of bones expresses divine will, they were not averse to lending a helping hand to the gods. Photo: Vassil / Creative Commons.

The Computing Aesthetic video is one of about 20,000 of the same YouTube videos marked “Peggle” and “Lucky.” Clips were loaded by players so overwhelmed by the luck in the game that they could not help but share their achievements with the world. But these players may not be as lucky as they seem. “The seemingly random bounce of the balls from the pins in Peggle was sometimes controlled by the game to provide the player with good results,” one of the game's developers, Jason Kapalka, admitted to me. “Occasionally, a“ successful bounce ”was used to ensure that the ball hit the pin instead of a failure in the“ dead ”zone. But we also added “good luck” to the players in half a dozen first levels so that they would not be so annoyed by the learning curve. ” According to Kapalka, a small correction of the direction of the rebound by several degrees (but not so much

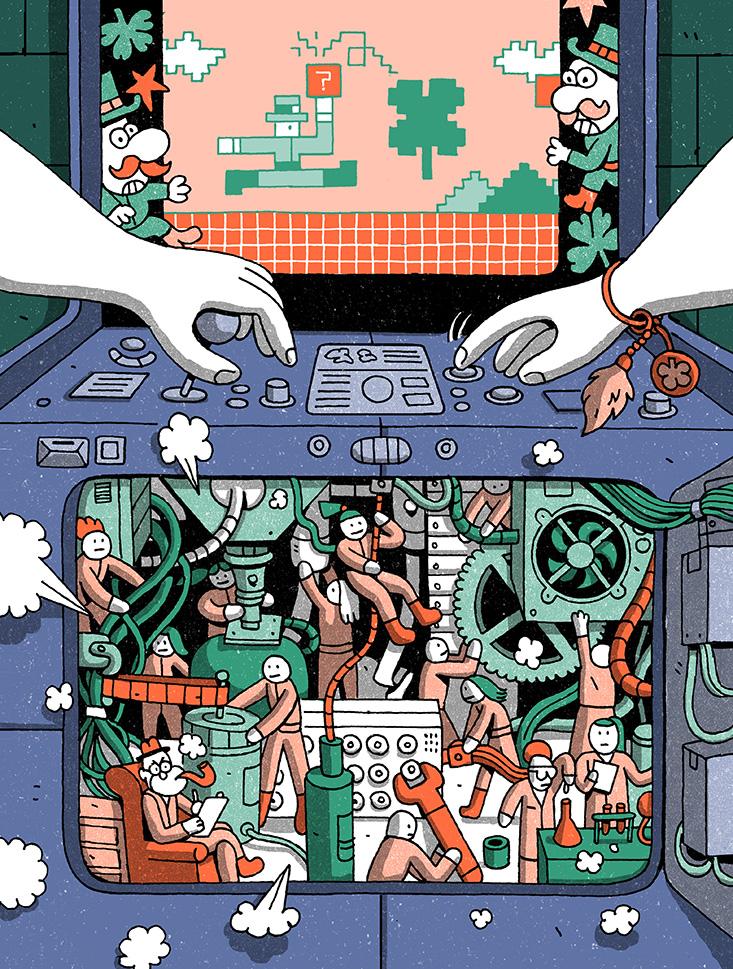

Most video games mean honesty. Managed by an all-knowing and omnipotent designer, the game should be as fair as possible, and players expect this. (Designers have an incentive not to cheat: they soon stop playing a game that always wins.) However, when video games do play by the rules, players may feel cheated. Sid Meier, the designer of the computer game Civilization, in which players lead their people through centuries of history, politics and wars, quickly learned to change the odds inside the game to compensate for this psychological problem. Thorough testing of the game showed that when a player who was predicted to have a 33 percent chance of winning the battle lost three times in a row, he felt anger and distrust. (In Civilization, you can replay the same battle until victory, incurring losses with each loss.) Therefore, Meyer changed the game to better match the cognitive distortion of a person. If the chances of winning the battle are one to three, the game ensures that you win the third attempt. This is a violation of the true principle of probability, which, however, introduced the illusion of honesty. Let's call it the “good luck paradox”: luck is great, but luckiness is unrealistic. The final unspoken agreement between players and designers can be considered the most abstract of the "social contracts." Let's call it the “good luck paradox”: luck is great, but luckiness is unrealistic. The final unspoken agreement between players and designers can be considered the most abstract of the "social contracts." Let's call it the “good luck paradox”: luck is great, but luckiness is unrealistic. The final unspoken agreement between players and designers can be considered the most abstract of the "social contracts."

In ancient times, luck was usually attributed to divine intervention: games were both fun for the gods and a test of human qualities. Luck is the central component of the games of the ancient Egyptians; according to Plato, the Egyptian god Thoth invented dice. In practice, bones were usually made from the talus of ungulates, they were polished and used in Egyptian board games and fortune telling on bones. In the graves, along with ancient game boards, fraudulent "charged" bones were found. Even if the ancient Egyptians believed that throwing a bone somehow expresses divine will, they did not mind helping her a little.

The 11th-century Norwegian king Olaf Haraldsson once put at stake the kingdom dice. Olaf had territorial disagreements with the Swedish king regarding the island of Hising. In the end, both agreed to resolve the issue by throwing bones. The Swedish king threw two sixes, the maximum number of points, and said that there was no point in continuing the game. Olaf insisted on his throw: having recently adopted Christianity, he was sure that God would turn the bones in his favor. His faith was rewarded with two sixes. They continued to roll the dice, throwing twelve points each time. The case ended with the fact that during the last throw of Olaf, one of the bones broke into two parts, showing six and one. Lucky thirteen points helped him win the kingdom.

Luck is just as important in modern games, from shaking bones in a glass to treacherous Chance cards in Monopoly. But her role has changed: Man has taken power from the gods, and luck has become a design tool that can change the gameplay and player’s expectations. For example, it allows players with different skill levels to play together, reducing the benefits given by skills. New York-based designer Zach Gage recently decided to reinvent chess by introducing a significant element of luck. “Chess has always been a very balanced game, completely dependent on the skill of the player,” he says. “This is great if you want to find out who plays them better, but doesn’t work if you want to play an interesting game with friends of different levels.”

Really Bad Chess, by contrast, at the beginning of each game gives each player a randomly selected set of pieces. The sides do not mirror each other, so one player may end up with five queens, and the other a whole battalion of pawns. “It solves two problems,” says Gage. “Weak players may feel that they have a chance to beat the strong thanks to good pieces. And it’s becoming more difficult to evaluate the strength of opponents, even for a specialist. ” Here, as in poker, victory is determined by luck in the hand and the talent of the player. This design also allows Gage to secretly control the probability of the initial distribution. For example, you can increase the likelihood of distributing stronger pieces to a novice, and putting an experienced player at a disadvantage.

In mechanical games, luck is the only salvation of the player from the mechanism itself. In the early 1950s, Chicago-based pinball machine maker Gottlieb noticed that novice pinball players sometimes miss the ball in the very first seconds of the game. Therefore, he added an inverted V-shaped metal wall, which in the first seconds of the game rose above the flippers at the bottom of the machine so that the ball would not fall down. In more modern pinball machines, the blocking gates known as “ball saver” (the name was coined by Chicago Coin for its 1968 Gun Smoke machine) are controlled by software. The rise of the wall depends on the luck, which is implemented in the algorithm.

Intentional close blunder: slot machines often use the illusion of luck. It looks as if the player almost got a big jackpot, for example, the last bar of gold or a lemon scrolls down and stops nearby, almost making a jackpot.

In fully digital video games, luck is even more woven into the gameplay and needs to be actively simulated. When a soccer ball flies past a goalkeeper or a string of race cars inexplicably slows down so that a player can catch up with it, the game designer’s hand actually invisibly intervenes in the process. The purpose of this manipulation is to encourage the player and thus maintain his interest. But this trick needs to be used gracefully. A player who feels the secret help of the game will feel that he is being patronized. In the end, luck is luck only when it is truly unpredictable.

And here the problems begin.

When the gods controlled fortune, we could only pray to them for a good fate. Now the architects of our fate in games can be found on LinkedIn. Because of this knowledge, our sensitivity to chances that we consider unfair has increased, and designers need to compensate for it.

“As soon as a player finds out about any pseudo-randomness of a game, he risks losing the feeling of luck,” says designer Paul Sottosanti of Riot Games, the publisher of League of Legends (one of the most popular online games). Games in which players are given seemingly random rewards often use a mechanism known as the pity timer. It ensures that the player gets a seemingly random luck over the average interval of failures (from about 10 minutes to an hour, depending on the game). In World of Warcraft, every time you kill an enemy, players hope to get a legendary (especially powerful) game weapon. The legendary weapon has an infinitely small chance of falling out, but it also depends on the "compassion timer." “When a player just waits for the timer to fire, he may get tired,” Sottosanti says. “The first feeling

Some examples of pseudo-randomness are designed to provide a sense of honesty, while others are invented for profit. With the rise of the so-called freemium games — free games making real games selling virtual items — the temptation has been to manipulate what looks like a coincidence to stimulate further spending. Sottosanti cites the popular virtual card game Hearthstone as a good example of compassion timers. “The chance of getting a valuable card increases with each set that it does not contain. The player is actually guaranteed to receive a valuable card after opening 40 sets. ” Kits are sold to players for money.

This technique is taken directly from the book of the American psychologist B. Skinner (BF Skinner). Skinner found that no matter who participated in the experiment: a pigeon, a rat, or a person, the most effective way to reinforce learned behavior is to reward according to a random schedule. Free game developers have found that randomly giving out small rewards can keep players interested (and buying) longer.

Natasha Schüll is an associate professor of media, culture, and communications at New York University, and the author of Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (Addictive Target: Slot Machines in Las Vegas). According to her, when a player feels that good luck favors him, “this can be attributed to the dumping of certain neurotransmitters and the release of dopamine. Even the obsessive search and the desire to restore this feeling of euphoria is controlled by the center of pleasure in the brain. ” The ability of dopamine to turn us into luck hunters is most clearly seen in the effects of certain drugs used to treat Parkinson's syndrome. It is noticed that flooding the brain with dopamine, they turn patients into ludomania.

The temptation to manipulate probabilities to form the attachment of the human brain is greatest in the gambling industry. Whether the game is played on the Internet or on a slot machine in a casino, usually the program controls the calculations. The results of the game of any modern slot machine are based on secret random number generators in computer networks, and not from the happy coincidence of pictures on three wooden cylinders. But losing with such a system of "luck" can be depressing. Therefore, the illusion of physical luck is often used in slot machines. It looks as if the player almost got a big jackpot, for example, the last bar of gold or a lemon scrolls down and stops nearby, almost making a jackpot. This entices players to keep betting on odds that remain meager.

“Close misses give rise to mixed feelings,” explains Luke Clark, psychologist and director of the University of British Columbia’s Gambling Studies Center. “On the one hand, close misses cause disgust, but at the same time increase motivation. On slot machines, a close miss increases the likelihood of a continuation of the game, because the player feels that he is starting to play better. ”

For games heavily dependent on luck, maintaining this illusion of perfection and control is crucial. "The most important role in this case is played by the structure of the brain called the striatum, the accumulation of nuclei in the center of the brain that regulates movement and reward." This area of the brain makes a particularly strong contribution to the feeling that we “grabbed our luck”. “The same area is involved in the formation of habits, which is obviously also related to addiction.”

By convincing the player that he is improving in a game based on luck, we, in turn, increase the likelihood that he will bet on non-winning chances. “Over the years of its existence, the gambling industry has been able to track the actions of individual players, create full-fledged profiles of average customers and use algorithms that predict the way out of the game,” says Schül. Operators of digital gaming machines have the opportunity, based on these profiles, to change the chances of winning directly during the gaming session. This way they can tempt players to continue the game. Many countries have laws prohibiting such manipulations of "luck." To get around them, casino operators established the position of the so-called “luck ambassadors”. They visit the casino and give players cash prizes, so that they invest in the game. Freemium games that are not yet subject to such legal restrictions can freely give players bonuses so that they feel successful and continue to play, spending their money.

Some designers generally abandoned the use of "leverage of luck." For a long time, the famous developer of pinball machines, Larry DeMar, who worked with Williams, did not use the ball saver walls in the company's machines, believing that they destroy the purity of the game. If you lose, then you lose, no luck.

Unfortunately, this approach does not always attract players. “Today, players almost always see patterns of manipulation where they are not there,” says Peggle developer Jason Kapalka. “When I was working on online games, it was almost impossible to convince some players that the results were somehow not falsified. People built detailed theories that newcomers are given better results to tie them to a paid subscription, or that old players are rewarded for their persistence, and so on. ” At some point, Kapalka published voluminous files with hundreds of thousands of simulated dice rolls to convince skeptical players of the true randomness of the results.

Game designers themselves can also be confused. “Even an experienced designer can get confused in a fairly large project,” the experienced designer Adam Saltsman told me. "And even an experienced player can misunderstand the system, taking the skill for luck, or vice versa."

If a game for a person is a way of preparing for life, then it is logical that we need to add uncertainties to our games, moments of inconstancy, to which we will have to adapt our attitude and strategies. But we have become more demanding on how luck should serve us in games - not too much, but not too little. Our interest in the nature of the luck we are experiencing remains unchanged. “When we meet with luck in the game, we feel a deep sense of alignment and coherence, almost the same as if we discovered a pattern and were able to predict it,” says Schül.

The source of this luck - whether it be the gods or the random distribution of probabilities - is a property of culture. But the promise of meeting good luck in the game comforts everyone: we found what we were looking for.

About the Author: Simon Parkin is the author of Death by Video Game: Danger, Pleasure, and Obsession on the Virtual Frontline (essay and articles in various publications), essays and articles in various publications. , including newyorker.com, The Guardian, The New York Times, MIT Technology Review, and New Statesman.