What is TLS

This text is a free translation of this chapter of the wonderful book "High Performance Browser Networking" by Ilya Grigorik. The translation was carried out as part of writing a term paper, therefore it is very free, but nevertheless it will be useful to those who have little idea of what TLS is and what it is eaten with.

The TLS (transport layer security) protocol is based on the SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) protocol, originally developed by Netscape to enhance e-commerce security on the Internet. SSL was implemented at the application level, directly over TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), which allows higher-level protocols (such as HTTP or email protocol) to work without changes. If SSL is configured correctly, then a third-party observer can only find out the connection parameters (for example, the type of encryption used), as well as the transmission frequency and the approximate amount of data, but cannot read and modify them.

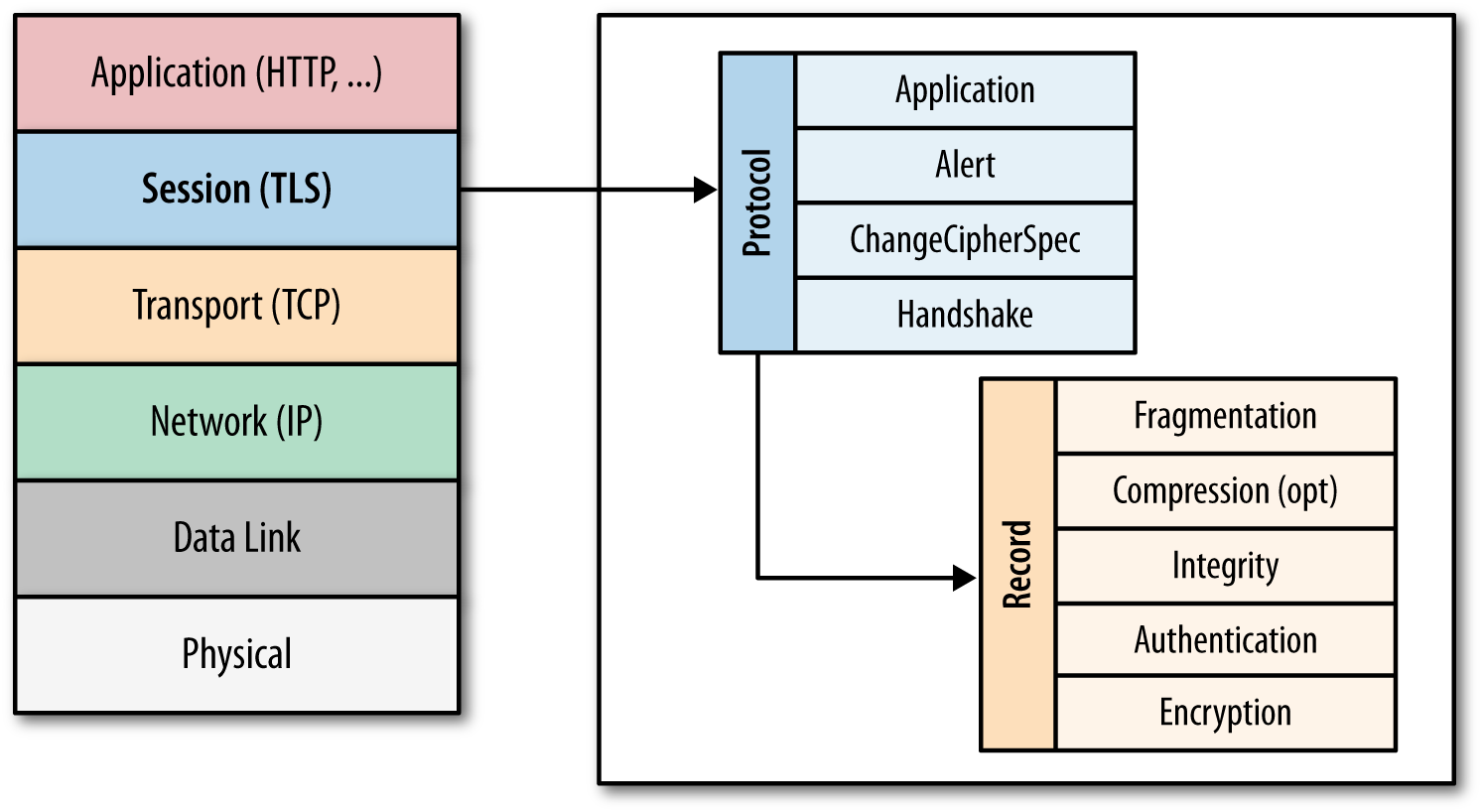

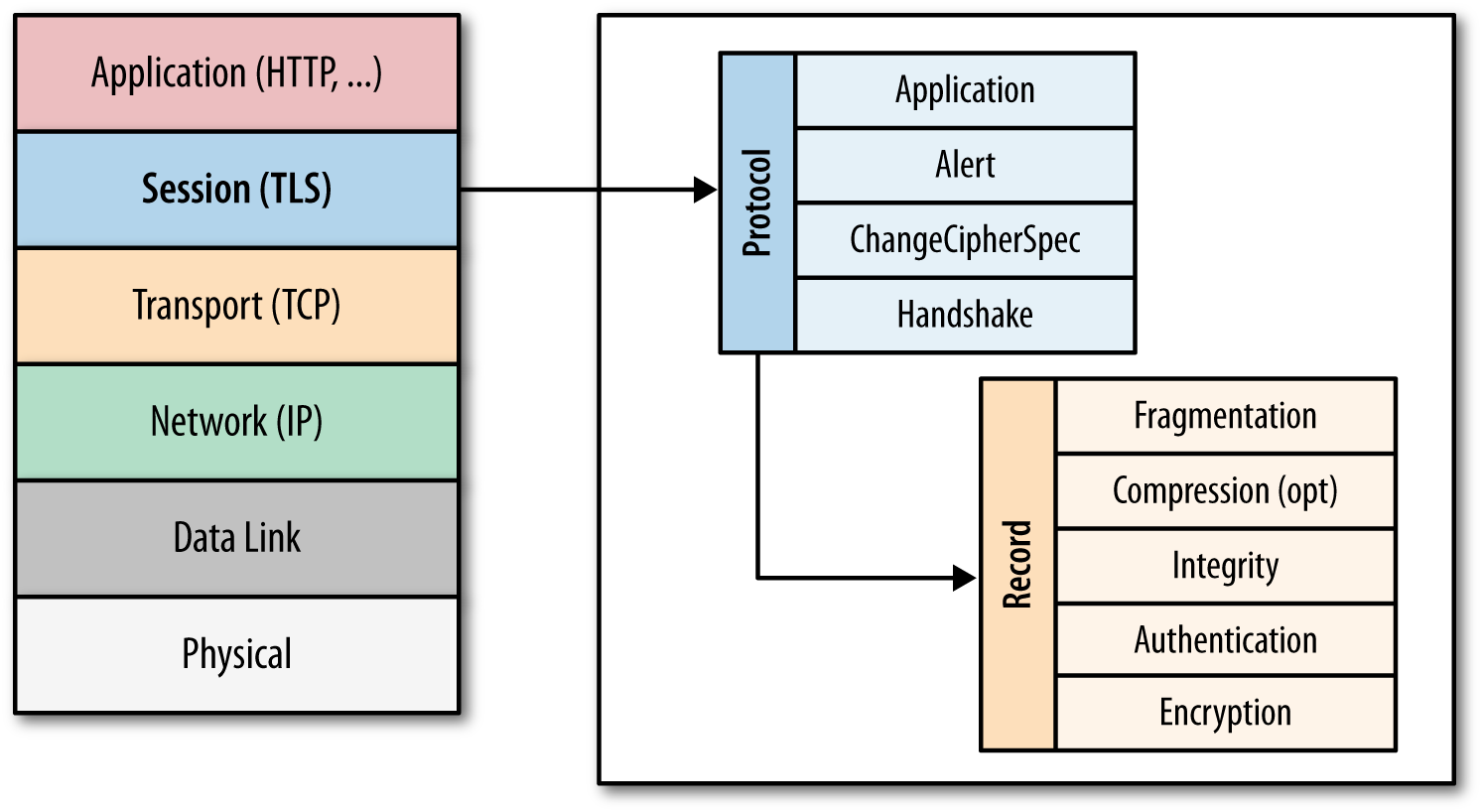

The specific place of TLS (SSL) in the Internet protocol stack is shown in the diagram:

After SSL was standardized by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), it was renamed TLS. Therefore, although the SSL and TLS names are interchangeable, they are still different, since each describes a different version of the protocol.

The first released version of the protocol was called SSL 2.0, but was quickly replaced by SSL 3.0 due to vulnerabilities discovered. As already mentioned, SSL was developed by Netscape, so in January 1999, the IETF openly standardized it under the name TLS 1.0. Then, in April 2006, TLS 1.1 was published, which expanded the original capabilities of the protocol and covered known vulnerabilities. The current version of the protocol at the moment is TLS 1.2, released in August 2008.

As already mentioned, TLS was designed to work on TCP, but to work with datagram protocols such as UDP (User Datagram Protocol), a special version of TLS was developed, called DTLS (Datagram Transport Layer Security).

The TLS protocol is designed to provide three services to all applications working on it, namely: encryption, authentication and integrity. Technically, not all three can be used, but in practice, to ensure safety, as a rule, all three are used:

In order to establish a cryptographically secure data channel, the connection nodes must agree on the encryption methods and keys used. The TLS protocol unambiguously defines this procedure; for more details, see TLS Handshake. It should be noted that TLS uses public key cryptography, which allows nodes to establish a common secret encryption key without any prior knowledge of each other.

Also, as part of the TLS Handshake procedure, it is possible to establish the identity of both the client and the server. For example, a client can be sure that the server that provides him with bank account information is indeed a bank server. And vice versa: the company’s server can be sure that the client connecting to it is the company’s employee, and not a third party (this mechanism is called Chain of Trust and will be discussed in the corresponding section).

Finally, TLS provides the sending of each message with a MAC (Message Authentication Code), the algorithm for creating which is a one-way cryptographic hashing function (in fact, a checksum), the keys of which are known to both parties in communication. Whenever a message is sent, its MAC value is generated, which the receiver can also generate, this ensures the integrity of information and protection against its substitution.

Thus, all three mechanisms underlying the cryptographic security of the TLS protocol are briefly reviewed.

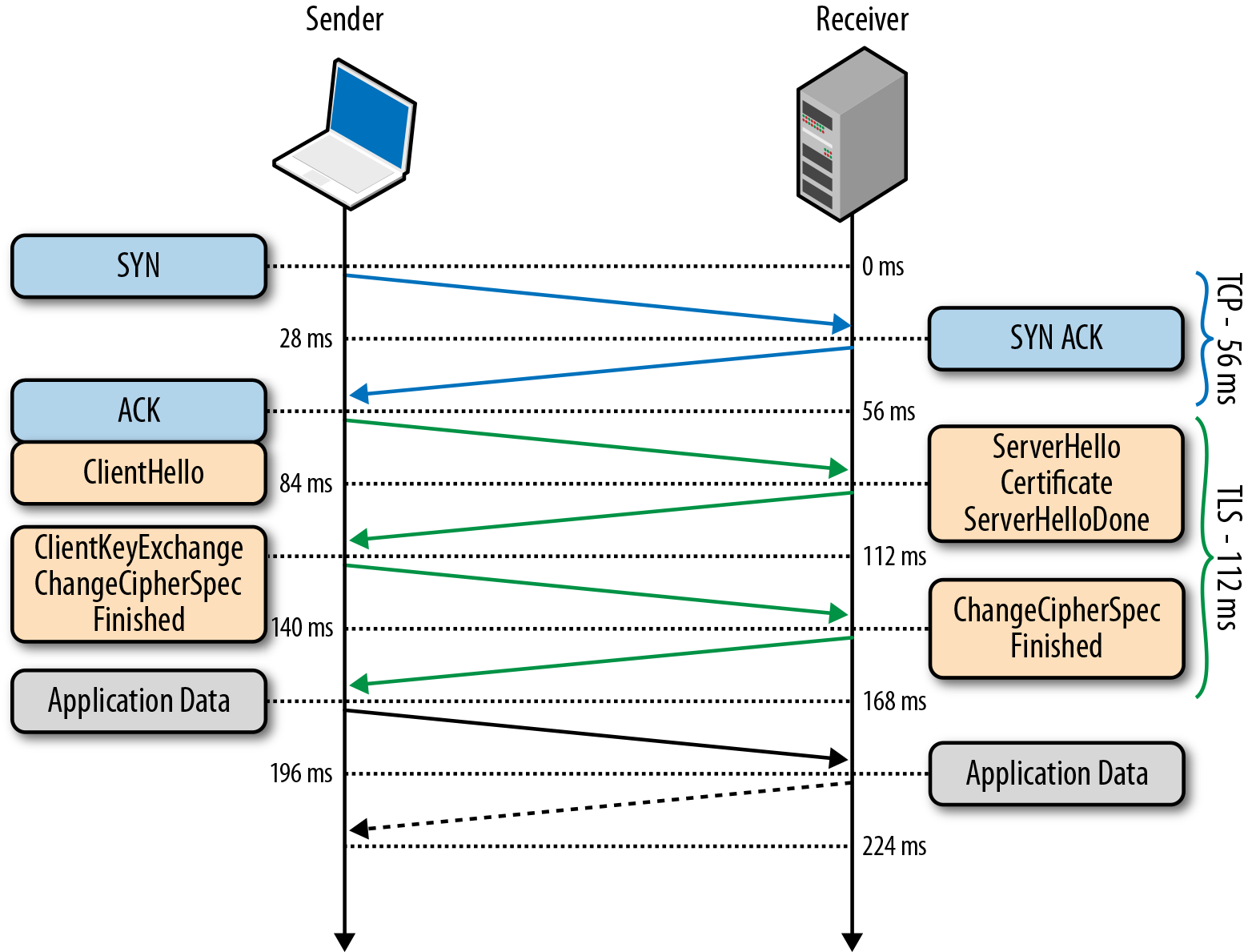

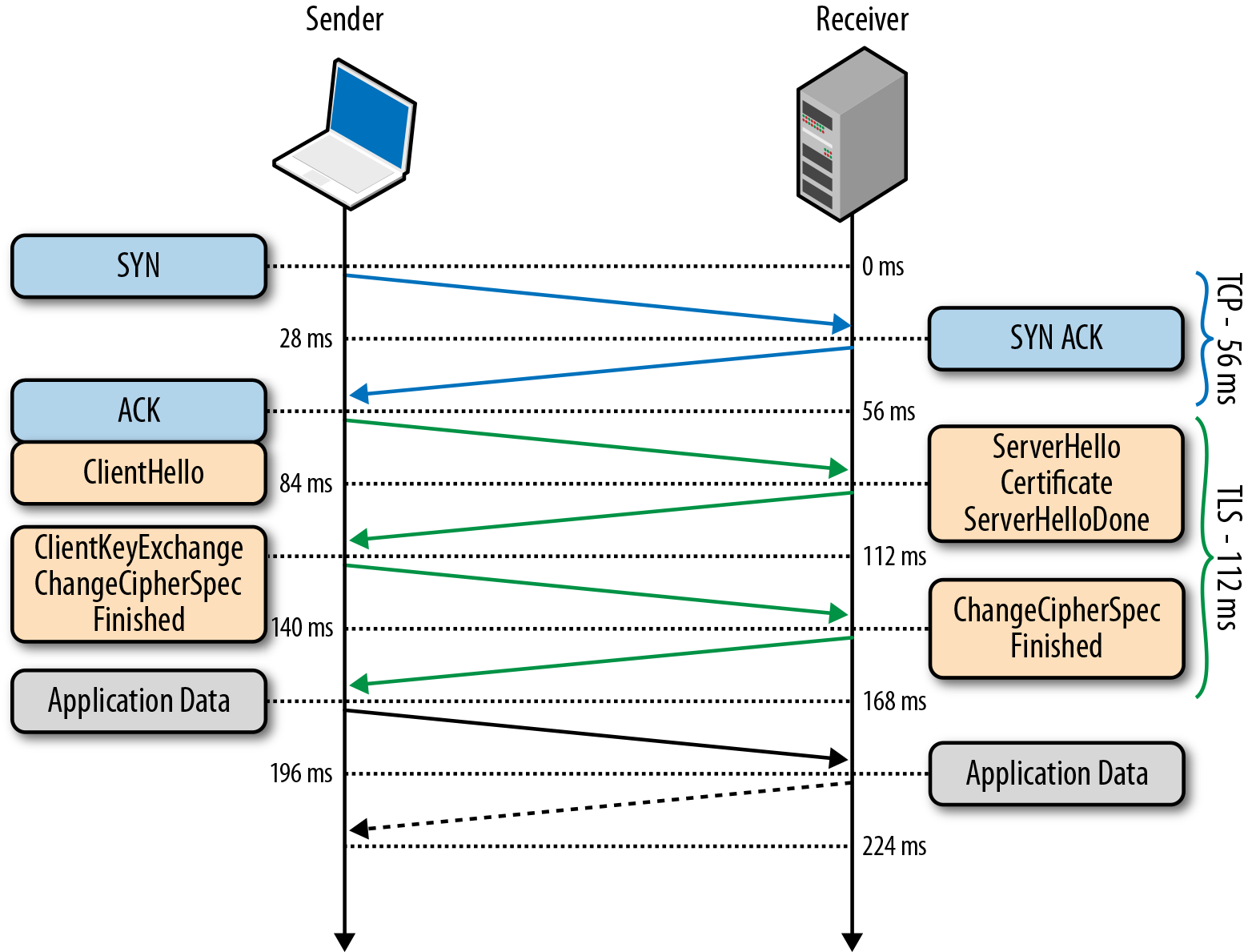

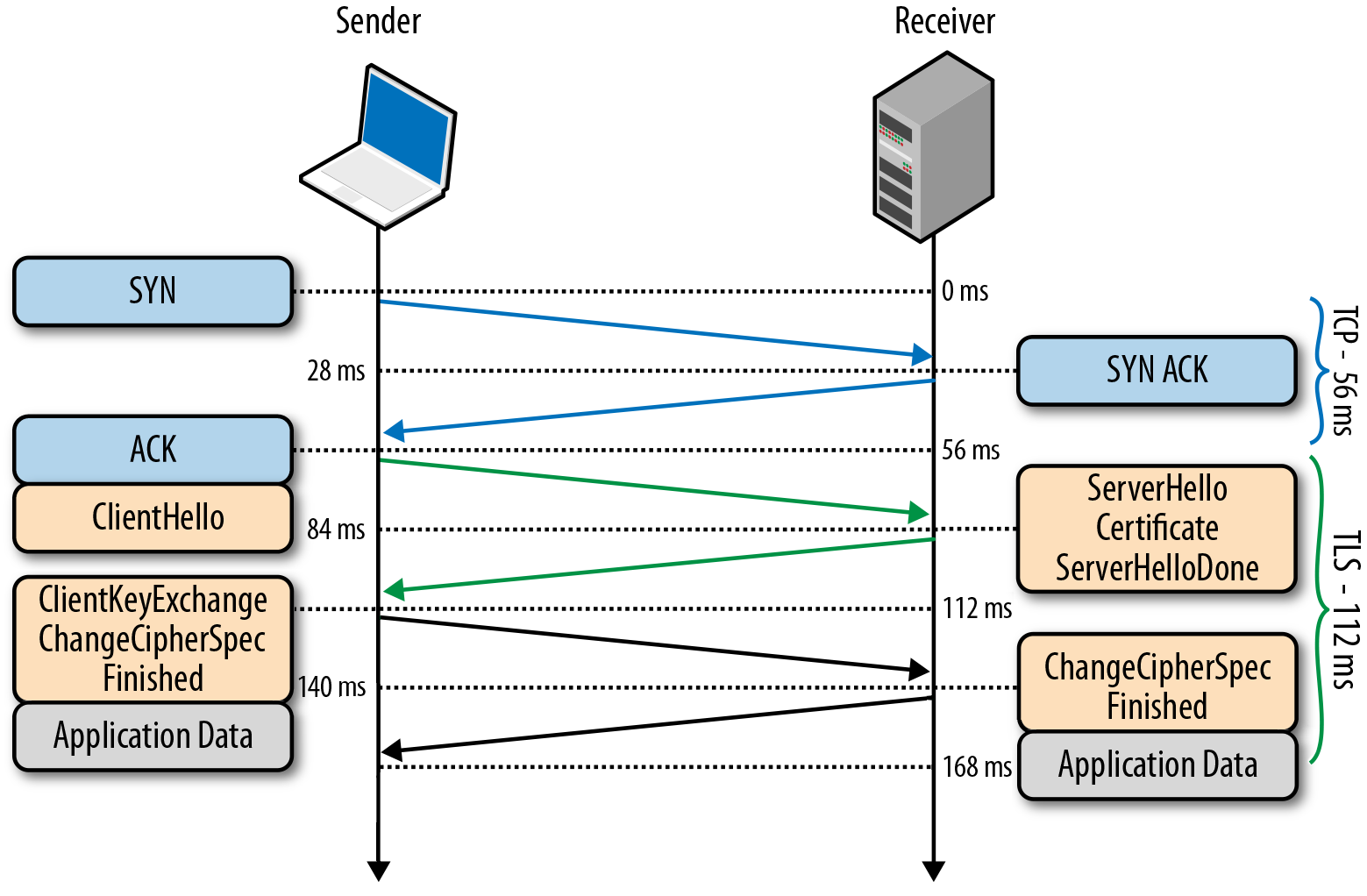

Before starting the exchange of data via TLS, the client and server must agree on the connection parameters, namely: the version of the protocol used, the method of data encryption, and also check the certificates, if necessary. The connection start diagram is called TLS Handshake and is shown in the figure:

We will analyze in more detail each step of this procedure:

It is clear that establishing a TLS connection is, generally speaking, a lengthy and time-consuming process, therefore there are several optimizations in the TLS standard. In particular, there is a procedure called “abbreviated handshake”, which allows you to use previously agreed parameters to restore the connection (naturally, if the client and server established a TLS connection in the past). This procedure is discussed in more detail in the “Resume Session” paragraph.

There is also an additional extension to the Handshake procedure called TLS False Start. This extension allows the client and server to begin exchanging encrypted data immediately after setting the encryption method, which reduces the connection establishment by one iteration of messages. This is described in more detail in the paragraph “TLS False Start”.

For various historical and commercial reasons, TLS most often uses RSA key exchange: the client generates a symmetric key, signs it using the server’s public key, and sends it to the server. In turn, on the server, the client key is decrypted using the private key. After that, the key exchange is declared completed. This algorithm has one drawback: the same pair of public and private keys is also used for server authentication. Accordingly, if an attacker gains access to the server’s private key, he can decrypt the entire communication session. Moreover, an attacker can simply record the entire communication session in an encrypted version and take decryption later, when it is possible to obtain the server’s private key. At the same time, the Diffie-Hellman key exchange seems more secure, since the installed symmetric key never leaves the client or server and, accordingly, cannot be intercepted by an attacker, even if he knows the server’s private key. The service for reducing the risk of compromising past communication sessions is based on this: a new, so-called “temporary” symmetric key is created for each new communication session. Accordingly, even in the worst case (if the attacker knows the server’s private key), the attacker can only obtain keys from future sessions, but not decrypt previously recorded ones. the so-called "temporary" symmetric key. Accordingly, even in the worst case (if the attacker knows the server’s private key), the attacker can only obtain keys from future sessions, but not decrypt previously recorded ones. the so-called "temporary" symmetric key. Accordingly, even in the worst case (if the attacker knows the server’s private key), the attacker can only obtain keys from future sessions, but not decrypt previously recorded ones.

At the moment, all browsers, when establishing a TLS connection, prefer the combination of the Diffie-Hellman algorithm and the use of temporary keys to increase the security of the connection.

It should be noted once again that public key encryption is used only in the TLS Handshake during the initial setup of the connection. After the tunnel is configured, symmetric cryptography comes into play, and communication within the current session is encrypted with the specified symmetric keys. This is necessary to increase performance, since public-key cryptography requires significantly more computing power.

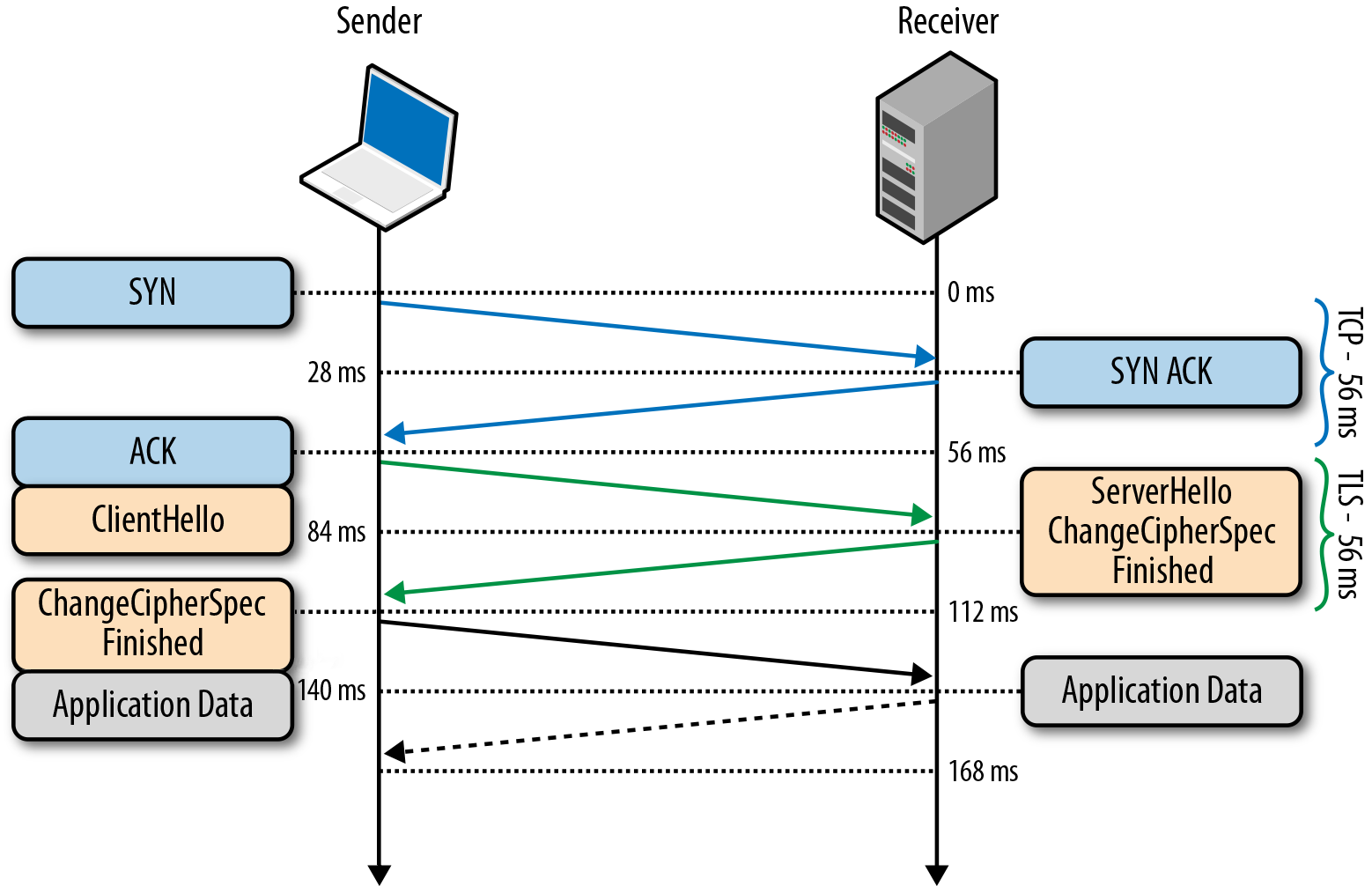

As noted earlier, the full TLS Handshake procedure is quite lengthy and expensive in terms of computational cost. Therefore, a procedure was developed that allows you to resume a previously aborted connection based on already configured data.

Starting with the first public version of the protocol (SSL 2.0), a server within the TLS Handshake (namely, the initial ServerHello message) can generate and send a 32-byte session identifier. Naturally, in this case, the server stores a cache of generated identifiers and session parameters for each client. In turn, the client stores the sent identifier and includes it (of course, if there is one) in the initial ClientHello message. If both the client and server have identical session identifiers, then the general connection is established using the simplified algorithm shown in the figure. If not, the full version of the TLS Handshake is required.

The procedure for resuming a session allows you to skip the stage of generating a symmetric key, which significantly increases the connection setup time, but does not affect its security, since previously uncompromised data from the previous session is used.

However, there is a practical limitation: since the server must store data about all open sessions, this leads to a problem with popular resources that are simultaneously requested by thousands and millions of clients.

To circumvent this problem, the Session Ticket mechanism was developed, which eliminates the need to save each client's data on the server. If the client during the initial connection setup indicated that it supports this technology, then during TLS Handshake sends the so-called Session Ticket to the client - session parameters encrypted with the server’s private key. At the next resumption of the session, the client, together with ClientHello, sends its existing Session Ticket. Thus, the server eliminates the need to store data about each connection, but the connection is still safe, since the Session Ticket is encrypted with a key known only on the server.

The technology of resuming a session undoubtedly improves protocol performance and reduces computational costs, however, it is not applicable in the initial connection to the server, or in the case when the previous session has already expired.

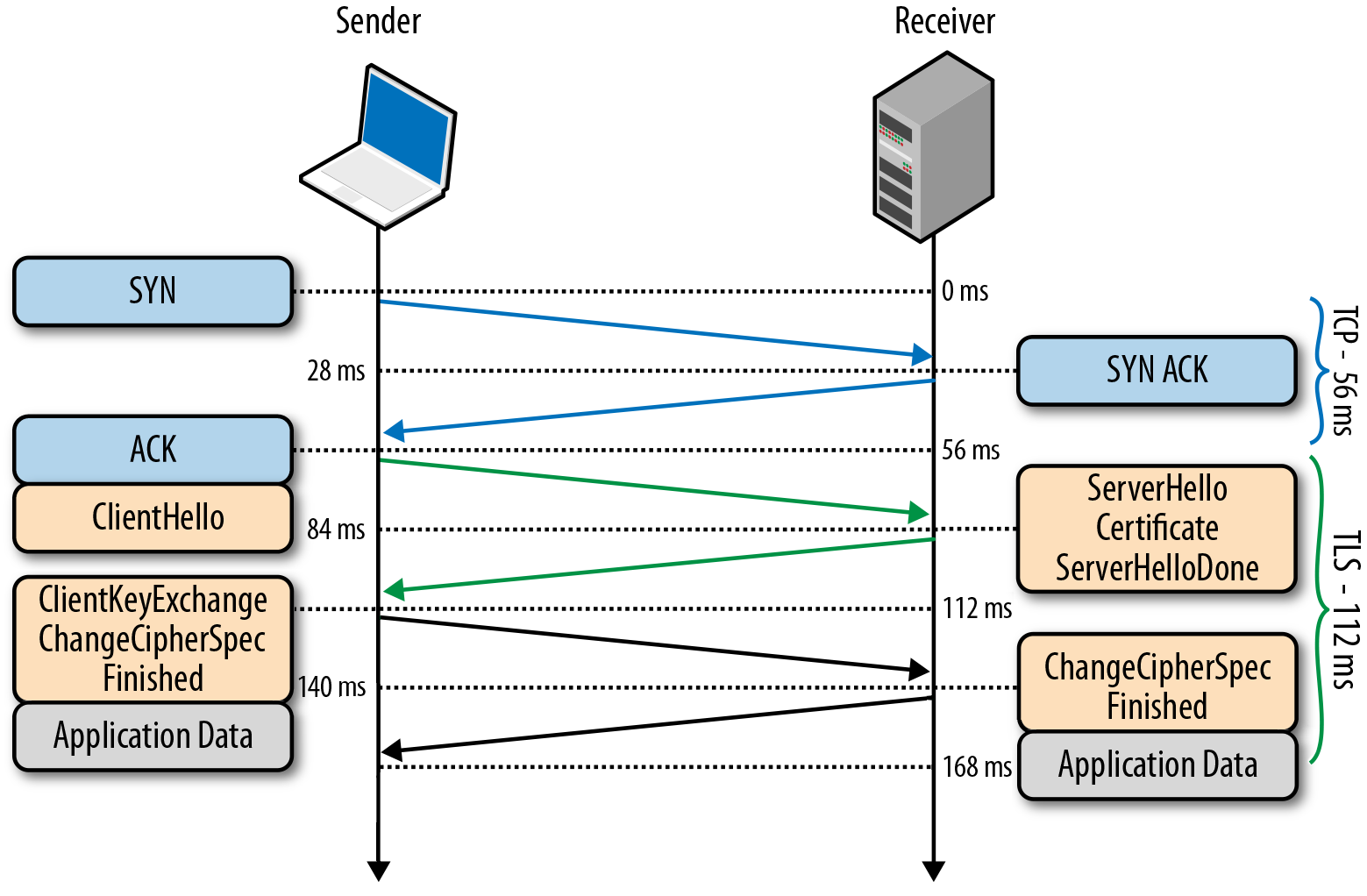

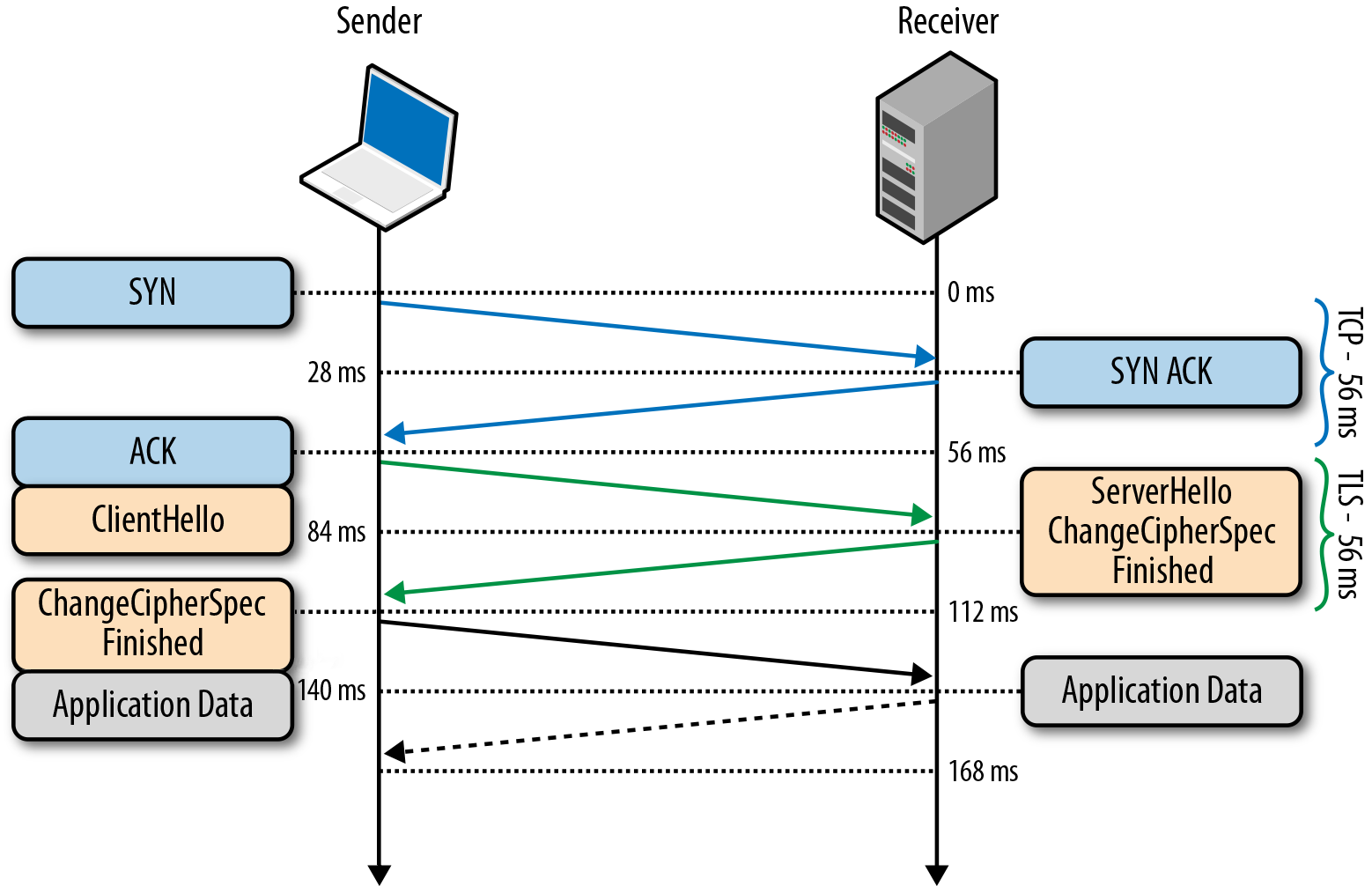

To obtain even greater performance, TLS False Start technology was developed, which is an optional extension of the protocol and allows sending data when the TLS Handshake is only partially completed. A detailed TLS False Start diagram is shown in the figure:

It is important to note that TLS False Start does not change the TLS Handshake procedure in any way. It is based on the assumption that at the moment when the client and server already know about the connection parameters and symmetric keys, application data can already be sent, and all necessary checks can be carried out in parallel. As a result, the connection is ready to be used one iteration of messaging earlier.

Authentication is an integral part of every TLS connection. Consider the simplest authentication process between Alice and Bob:

Obviously, this scheme is built on trust between Alice and Bob. It is assumed that the exchange of public keys occurred, for example, in a personal meeting, and thus, Alice is sure that she received the key directly from Bob, and Bob, in turn, is sure that he received Alice’s public key.

Now let Alice receive a message from Charlie, whom she is not familiar with, but who claims to be friends with Bob. To prove this, Charlie asked in advance to sign his own public key with Bob's private key, and attaches this signature to Alice's message. Alice first checks Bob’s signature on Charlie’s key (she’s able to do this, because she already knows Bob’s public key), makes sure that Charlie is really Bob’s friend, accepts his message and performs the well-known integrity check, making sure that the message is from Charlie :

Described in the previous paragraph is the creation of a “chain of trust” (or “Chain of trust”, if in English).

In TLS, these trust chains are based on certificates of authenticity provided by special authorities called certificate authorities (CAs). Certificate authorities perform checks and if the issued certificate is compromised, then this certificate is revoked.

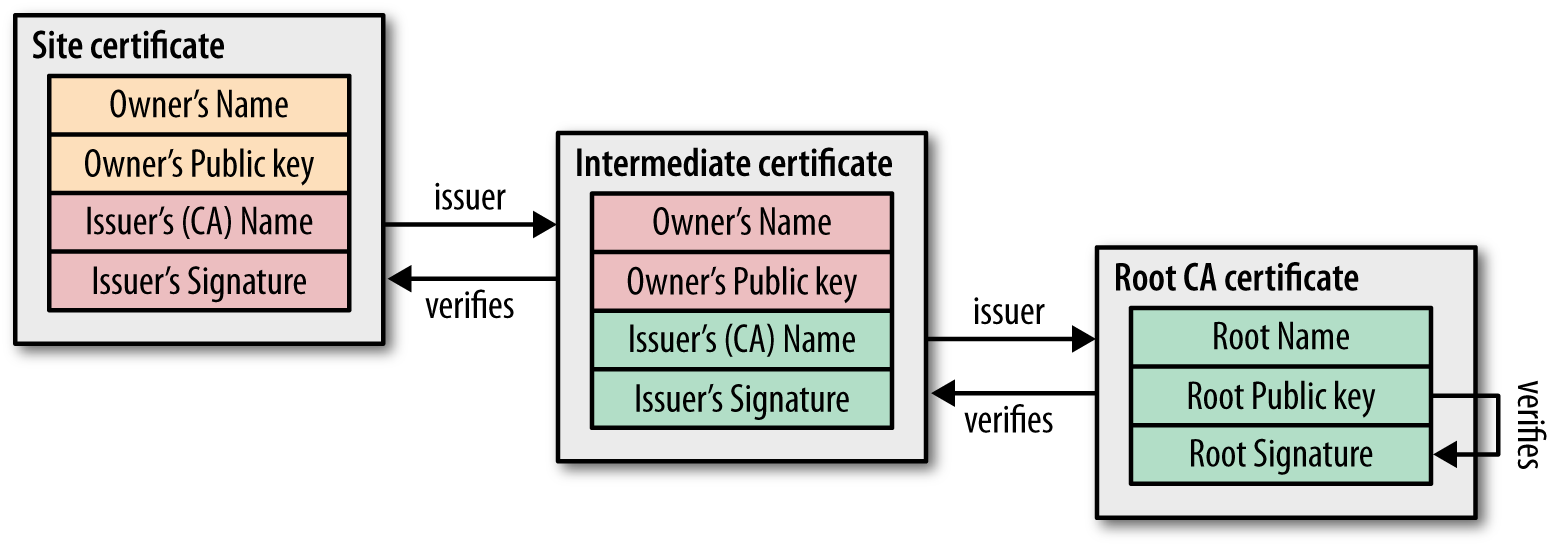

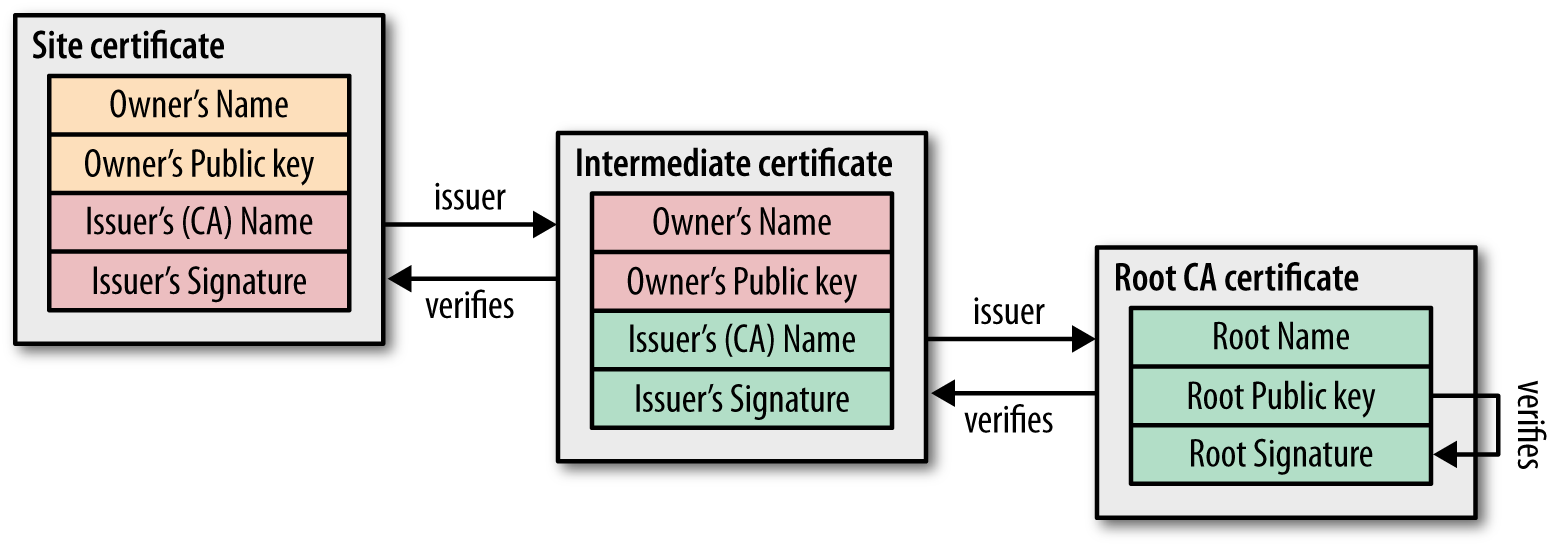

From the issued certificates, the already considered chain of trust is added up. Its root is the so-called “Root CA certificate” - a certificate signed by a major center, the credibility of which is undeniable. In general, the chain of trust looks something like this:

Naturally, there are cases when an already issued certificate needs to be revoked or revoked (for example, the private key of the certificate was compromised, or the entire certification procedure was compromised). For this, certificates of authenticity contain special instructions on checking their relevance. Therefore, when building a chain of trust, it is necessary to check the relevance of each trust node.

The mechanism of this check is simple and is based on the so-called "Certificate Revocation List" (CRL - "Certificate Revocation List"). Each certification authority has this list, which is a simple list of serial numbers of revoked certificates. Accordingly, anyone who wants to verify the authenticity of a certificate simply downloads this list and looks for the number of the verified certificate in it. If the number is detected, it means that the certificate has been revoked.

There is obviously some technical irrationality here: to verify only one certificate, you need to request the entire list of revoked certificates, which leads to a slowdown. To combat this, a mechanism called the “Online Certificate Status Protocol” (OCSP) was developed. It allows you to check the status of a certificate dynamically. Naturally, this reduces the load on network bandwidth, but at the same time causes several problems:

Actually, in all modern browsers, both solutions (OCSP and CRL) complement each other, moreover, as a rule, there is the possibility of setting the preferred policy for checking certificate status.

Thus, this article discusses all the key tools provided by the TLS protocol to protect information. For some gag in the article, I apologize, these are the costs of the original purpose of the translation.

TLS Overview

The TLS (transport layer security) protocol is based on the SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) protocol, originally developed by Netscape to enhance e-commerce security on the Internet. SSL was implemented at the application level, directly over TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), which allows higher-level protocols (such as HTTP or email protocol) to work without changes. If SSL is configured correctly, then a third-party observer can only find out the connection parameters (for example, the type of encryption used), as well as the transmission frequency and the approximate amount of data, but cannot read and modify them.

The specific place of TLS (SSL) in the Internet protocol stack is shown in the diagram:

After SSL was standardized by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), it was renamed TLS. Therefore, although the SSL and TLS names are interchangeable, they are still different, since each describes a different version of the protocol.

The first released version of the protocol was called SSL 2.0, but was quickly replaced by SSL 3.0 due to vulnerabilities discovered. As already mentioned, SSL was developed by Netscape, so in January 1999, the IETF openly standardized it under the name TLS 1.0. Then, in April 2006, TLS 1.1 was published, which expanded the original capabilities of the protocol and covered known vulnerabilities. The current version of the protocol at the moment is TLS 1.2, released in August 2008.

As already mentioned, TLS was designed to work on TCP, but to work with datagram protocols such as UDP (User Datagram Protocol), a special version of TLS was developed, called DTLS (Datagram Transport Layer Security).

Encryption, Authentication, and Integrity

The TLS protocol is designed to provide three services to all applications working on it, namely: encryption, authentication and integrity. Technically, not all three can be used, but in practice, to ensure safety, as a rule, all three are used:

- Encryption - hiding information transmitted from one computer to another;

- Authentication - verification of authorship of transmitted information;

- Integrity - detection of falsification of information substitution.

In order to establish a cryptographically secure data channel, the connection nodes must agree on the encryption methods and keys used. The TLS protocol unambiguously defines this procedure; for more details, see TLS Handshake. It should be noted that TLS uses public key cryptography, which allows nodes to establish a common secret encryption key without any prior knowledge of each other.

Also, as part of the TLS Handshake procedure, it is possible to establish the identity of both the client and the server. For example, a client can be sure that the server that provides him with bank account information is indeed a bank server. And vice versa: the company’s server can be sure that the client connecting to it is the company’s employee, and not a third party (this mechanism is called Chain of Trust and will be discussed in the corresponding section).

Finally, TLS provides the sending of each message with a MAC (Message Authentication Code), the algorithm for creating which is a one-way cryptographic hashing function (in fact, a checksum), the keys of which are known to both parties in communication. Whenever a message is sent, its MAC value is generated, which the receiver can also generate, this ensures the integrity of information and protection against its substitution.

Thus, all three mechanisms underlying the cryptographic security of the TLS protocol are briefly reviewed.

TLS Handshake

Before starting the exchange of data via TLS, the client and server must agree on the connection parameters, namely: the version of the protocol used, the method of data encryption, and also check the certificates, if necessary. The connection start diagram is called TLS Handshake and is shown in the figure:

We will analyze in more detail each step of this procedure:

- Since TLS works on TCP, first a TCP connection is established between the client and server.

- After installing TCP, the client sends the specification in plain text to the server (namely, the version of the protocol that it wants to use, supported encryption methods, etc).

- The server approves the version of the protocol used, selects the encryption method from the list provided, attaches its certificate and sends a response to the client (if desired, the server can also request a client certificate).

- The protocol version and encryption method are considered approved at this moment, the client checks the certificate sent and initiates either RSA or Diffie-Hellman key exchange, depending on the settings.

- The server processes the message sent by the client, checks the MAC, and sends the client a final ('Finished') message in encrypted form.

- The client decrypts the received message, checks the MAC, and if everything is fine, then the connection is considered established and the exchange of application data begins.

It is clear that establishing a TLS connection is, generally speaking, a lengthy and time-consuming process, therefore there are several optimizations in the TLS standard. In particular, there is a procedure called “abbreviated handshake”, which allows you to use previously agreed parameters to restore the connection (naturally, if the client and server established a TLS connection in the past). This procedure is discussed in more detail in the “Resume Session” paragraph.

There is also an additional extension to the Handshake procedure called TLS False Start. This extension allows the client and server to begin exchanging encrypted data immediately after setting the encryption method, which reduces the connection establishment by one iteration of messages. This is described in more detail in the paragraph “TLS False Start”.

TLS Key Exchange

For various historical and commercial reasons, TLS most often uses RSA key exchange: the client generates a symmetric key, signs it using the server’s public key, and sends it to the server. In turn, on the server, the client key is decrypted using the private key. After that, the key exchange is declared completed. This algorithm has one drawback: the same pair of public and private keys is also used for server authentication. Accordingly, if an attacker gains access to the server’s private key, he can decrypt the entire communication session. Moreover, an attacker can simply record the entire communication session in an encrypted version and take decryption later, when it is possible to obtain the server’s private key. At the same time, the Diffie-Hellman key exchange seems more secure, since the installed symmetric key never leaves the client or server and, accordingly, cannot be intercepted by an attacker, even if he knows the server’s private key. The service for reducing the risk of compromising past communication sessions is based on this: a new, so-called “temporary” symmetric key is created for each new communication session. Accordingly, even in the worst case (if the attacker knows the server’s private key), the attacker can only obtain keys from future sessions, but not decrypt previously recorded ones. the so-called "temporary" symmetric key. Accordingly, even in the worst case (if the attacker knows the server’s private key), the attacker can only obtain keys from future sessions, but not decrypt previously recorded ones. the so-called "temporary" symmetric key. Accordingly, even in the worst case (if the attacker knows the server’s private key), the attacker can only obtain keys from future sessions, but not decrypt previously recorded ones.

At the moment, all browsers, when establishing a TLS connection, prefer the combination of the Diffie-Hellman algorithm and the use of temporary keys to increase the security of the connection.

It should be noted once again that public key encryption is used only in the TLS Handshake during the initial setup of the connection. After the tunnel is configured, symmetric cryptography comes into play, and communication within the current session is encrypted with the specified symmetric keys. This is necessary to increase performance, since public-key cryptography requires significantly more computing power.

Resuming TLS Session

As noted earlier, the full TLS Handshake procedure is quite lengthy and expensive in terms of computational cost. Therefore, a procedure was developed that allows you to resume a previously aborted connection based on already configured data.

Starting with the first public version of the protocol (SSL 2.0), a server within the TLS Handshake (namely, the initial ServerHello message) can generate and send a 32-byte session identifier. Naturally, in this case, the server stores a cache of generated identifiers and session parameters for each client. In turn, the client stores the sent identifier and includes it (of course, if there is one) in the initial ClientHello message. If both the client and server have identical session identifiers, then the general connection is established using the simplified algorithm shown in the figure. If not, the full version of the TLS Handshake is required.

The procedure for resuming a session allows you to skip the stage of generating a symmetric key, which significantly increases the connection setup time, but does not affect its security, since previously uncompromised data from the previous session is used.

However, there is a practical limitation: since the server must store data about all open sessions, this leads to a problem with popular resources that are simultaneously requested by thousands and millions of clients.

To circumvent this problem, the Session Ticket mechanism was developed, which eliminates the need to save each client's data on the server. If the client during the initial connection setup indicated that it supports this technology, then during TLS Handshake sends the so-called Session Ticket to the client - session parameters encrypted with the server’s private key. At the next resumption of the session, the client, together with ClientHello, sends its existing Session Ticket. Thus, the server eliminates the need to store data about each connection, but the connection is still safe, since the Session Ticket is encrypted with a key known only on the server.

TLS False Start

The technology of resuming a session undoubtedly improves protocol performance and reduces computational costs, however, it is not applicable in the initial connection to the server, or in the case when the previous session has already expired.

To obtain even greater performance, TLS False Start technology was developed, which is an optional extension of the protocol and allows sending data when the TLS Handshake is only partially completed. A detailed TLS False Start diagram is shown in the figure:

It is important to note that TLS False Start does not change the TLS Handshake procedure in any way. It is based on the assumption that at the moment when the client and server already know about the connection parameters and symmetric keys, application data can already be sent, and all necessary checks can be carried out in parallel. As a result, the connection is ready to be used one iteration of messaging earlier.

TLS Chain of trust

Authentication is an integral part of every TLS connection. Consider the simplest authentication process between Alice and Bob:

- Both Alice and Bob generate their own public and private keys.

- Alice and Bob exchange public keys.

- Alice generates a message, encrypts it with her private key and sends it to Bob.

- Bob uses the key received from Alice to decrypt the message and thus verifies the authenticity of the received message.

Obviously, this scheme is built on trust between Alice and Bob. It is assumed that the exchange of public keys occurred, for example, in a personal meeting, and thus, Alice is sure that she received the key directly from Bob, and Bob, in turn, is sure that he received Alice’s public key.

Now let Alice receive a message from Charlie, whom she is not familiar with, but who claims to be friends with Bob. To prove this, Charlie asked in advance to sign his own public key with Bob's private key, and attaches this signature to Alice's message. Alice first checks Bob’s signature on Charlie’s key (she’s able to do this, because she already knows Bob’s public key), makes sure that Charlie is really Bob’s friend, accepts his message and performs the well-known integrity check, making sure that the message is from Charlie :

Described in the previous paragraph is the creation of a “chain of trust” (or “Chain of trust”, if in English).

In TLS, these trust chains are based on certificates of authenticity provided by special authorities called certificate authorities (CAs). Certificate authorities perform checks and if the issued certificate is compromised, then this certificate is revoked.

From the issued certificates, the already considered chain of trust is added up. Its root is the so-called “Root CA certificate” - a certificate signed by a major center, the credibility of which is undeniable. In general, the chain of trust looks something like this:

Naturally, there are cases when an already issued certificate needs to be revoked or revoked (for example, the private key of the certificate was compromised, or the entire certification procedure was compromised). For this, certificates of authenticity contain special instructions on checking their relevance. Therefore, when building a chain of trust, it is necessary to check the relevance of each trust node.

The mechanism of this check is simple and is based on the so-called "Certificate Revocation List" (CRL - "Certificate Revocation List"). Each certification authority has this list, which is a simple list of serial numbers of revoked certificates. Accordingly, anyone who wants to verify the authenticity of a certificate simply downloads this list and looks for the number of the verified certificate in it. If the number is detected, it means that the certificate has been revoked.

There is obviously some technical irrationality here: to verify only one certificate, you need to request the entire list of revoked certificates, which leads to a slowdown. To combat this, a mechanism called the “Online Certificate Status Protocol” (OCSP) was developed. It allows you to check the status of a certificate dynamically. Naturally, this reduces the load on network bandwidth, but at the same time causes several problems:

- Certificate Authorities must handle the load in real time;

- Certificate Authorities must guarantee their availability at all times;

- Due to real-time requests, certification authorities receive information about which sites each particular user visited.

Actually, in all modern browsers, both solutions (OCSP and CRL) complement each other, moreover, as a rule, there is the possibility of setting the preferred policy for checking certificate status.

Thus, this article discusses all the key tools provided by the TLS protocol to protect information. For some gag in the article, I apologize, these are the costs of the original purpose of the translation.