Objective-C Runtime for C-Schnicks. Part 1

When I first met Objective-C, he impressed me with an ugly and illogical language. At that time, I already had a fairly strong base in C / C ++ and x86 assembler, and also was familiar with other high-level languages. The documentation wrote that Objective-C is an extension of the C language. But, no matter how hard I tried, I still could not apply my experience in developing applications for iOS.

Today, it still seems ugly to me. But once plunged into the depths of Objective-C Runtime, I fell in love with him. Studying Objective-C Runtime allowed me to find those thin strings that connect Objective-C with its “father” - the magnificent and unrivaled C language. This is the case when love turns flaws into virtues.

If you are interested in looking at Objective-C, not just as a set of operators and basic frameworks, but understanding its low-level device, please, use cat.

Small clarification

In my articles, I will often confuse Objective C, Objective-C Runtime, iOS SDK, iOS, iPhone, etc. Not because I don’t understand the difference between them, but because it will be easier to explain the essence of things without fanning articles to a comprehensive manual on C and BSD-based systems. Therefore, a big request to write comments with clarifications in terminology only where it really is of fundamental importance.

A little bit about "method calls"

Let's take a look at our usual construction:

[myObject someMethod];This is usually called a "call method". Meticulous iOS developers call this “send a message to an object,” which they are certainly right about. Because no matter what “methods” and whatever objects you call, in the end, such a construction will be transformed by the compiler into the most ordinary call to the objc_msgSend function:

objc_msgSend(myObject, @selector(someMethod));Thus, everything that the design we have taken does just call the objc_msgSend function.

From the name you can understand that there is some kind of message sending. We will talk about this function later, because already with the information we have on hand, we are faced with the @selector () construct, unknown to us, which I propose to understand first of all.

Meet the selectors

Having looked in the documentation , we find out that the signature of the objc_msgSend (...) function has the following form:

id objc_msgSend ( id self, SEL op, ... );Since an ordinary C-function takes an argument of type SEL as a parameter, then we can learn more about this type of SEL in more detail if we want to.

Based on the documentation , we learn that there are two ways to get a selector (for us, an object of type SEL):

- At compile time: SEL aSelector = @selector (methodName);

- At run time: SEL aSelector = NSSelectorFromString (@ "methodName");

Well, it is runtime that interests us, so again from the documentation we have the following information:

SEL NSSelectorFromString ( NSString *aSelectorName );To create a selector, NSSelectorFromString passes aSelectorName to the sel_registerName function as a UTF-8 string and returns the value obtained from the called function. Note also that if the selector does not exist, the newly registered selector will be returned.

This is already more interesting and closer to our Si-shny worldview. Interest awakens to dig a little deeper.

Here, of course, I understand that I’m already pretty tired of you with my links to the documentation, but in another way. Therefore, we again read the documentation for the sel_registerName method and, lo and behold, this function takes the most ordinary C-string as an argument!

SEL sel_registerName ( const char *str );Well, this is the maximum level that we can go down on the basis of documentation. All that is written about this function is that it registers the method in the Objective-C Runtime, converts the method name into a selector, and returns it.

In principle, this is enough for us to understand how the @selector () construct works. And if not enough, then you can see the source code of this function, it is available directly on the Apple website . First of all, the function is interesting in this file.

static SEL __sel_registerName(const char *name, int lock, int copy) {However, the incomprehensible moment is with the SEL type. All I managed to find was that it is a pointer to the objc_selector structure:

typedef struct objc_selector *SEL;I did not find the source code for the objc_selector structure. Somewhere there were references that this is a regular C-string, but this type is completely transparent and I should in no case go into the details of its implementation, because Apple can change it at any time. But for you and me this is not the answer to the question. Therefore, all that remains for us to do is arm ourselves with our beloved LLDB and get this information on our own.

To do this, we will write a simple code:

#import

int main(int argc, const char * argv[]) {

SEL mySelector = NSSelectorFromString(@"mySelector");

return 0;

} And add a breakpoint to the string “return 0;”.

Through simple manipulations with LLDB in Xcode, we find out that the variable mySelector is ultimately a regular C-string.

So what is this objc_selector structure that turns into a string in a weird way? If you try to create an object of type objc_selector, then you are unlikely to succeed. The fact is that the objc_selector structure simply does not exist. Apple developers used this hack to prevent C-strings from being compatible with SEL objects. Why? Because the mechanism of selectors can change at any time, and abstracting from the concept of C-lines will allow you to avoid troubles while further supporting your code.

Then it is logical to conclude that we can write the following code that should work:

#import

#import

@interface TestClass : NSObject

- (void)someMethod;

@end

@implementation TestClass

- (void)someMethod {

NSLog(@"Hello from method!");

}

@end

int main(int argc, const char * argv[]) {

TestClass * myObj = [[TestClass alloc] init];

SEL mySelector = (SEL)"someMethod";

objc_msgSend(myObj, mySelector);

return 0;

} But such code crashes with the following explanation:

2015-02-18 14: 03: 23.152 ObjCRuntimeTest [4756: 1861470] *** NSForwarding: warning: selector (0x100000f6d) for message 'someMethod' does not match selector known to Objective C runtime (0x100000f82) - abort

2015-02 -18 14: 03: 23.178 ObjCRuntimeTest [4756: 1861470] - [TestClass someMethod]: unrecognized selector sent to instance 0x1002069c0

Objective-C Runtime told us that he did not know about the selector we tried to operate with. And we already know why - we must register the selector with the sel_registerName () function.

Here I ask you to pay attention that I gave exactly two lines of error output. The fact is that when you simply operate on the selector that you received using @selector (someMethod) and send a message to some object, you will only get the error "unrecognized selector sent to instance". But in our case, we were told before this that Objective-C Runtime does not know such a selector. Based on this, we can conclude that selectors have nothing to do with objects. That is, if two objects of completely different classes have a method:

- (void)myMegaMethod;, then to call this method for both objects the same selector registered by you in runtime using the construct will be used

SEL myMegaSelector = @selector(myMegaMethod);What does a registered selector mean? In order not to go into the details of the implementation of sel_registerName (), I will explain it this way: you pass a C-string to this function, and in return it returns a copy of this string to you. Why a copy? Because it copies the identifier you transferred to its memory region that is more intelligible to it, and gives you a pointer to a string that is located in this very memory region that is "intelligible" to it. We will talk about this memory area later.

Summarizing

We read a lot of documentation, played with the debugger, but now we would have to summarize this matter in our S-shy heads.

Now we can make a "method call" exclusively by means of the C language:

SEL mySelector = sel_registerName("myMethod");

objc_msgSend(myObj, mySelector);That is, they did not lie to us: Objective-C is really compatible with the C language, being its extension.

On this I would like to finish the first part and allow you to enjoy this pleasant sensation, albeit of a small, but still understanding of the principles of operation of Objective-C Runtime.

Update

Thank you for pointing out to user 1101_debian how we came to the conclusion that the selector is a regular C-string. I'll try to clarify.

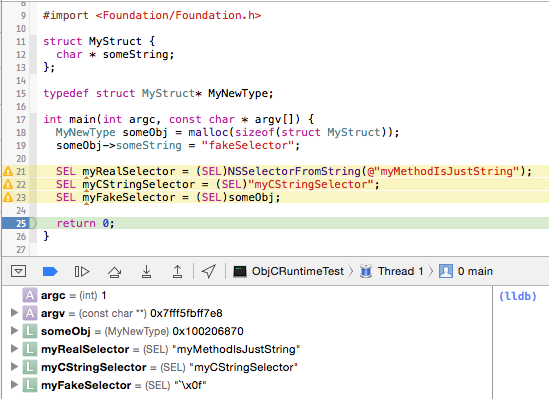

We came to this conclusion based on the output of the print mySelector command in the LLDB console. This can be seen in the screenshot. LLDB informed us that this is a string. If it were not a string, then LLDB would have deduced our selector accordingly. For example, if we run the code:

#import

struct MyStruct {

char * someString;

};

typedef struct MyStruct* MyNewType;

int main(int argc, const char * argv[]) {

MyNewType someObj = malloc(sizeof(struct MyStruct));

someObj->someString = "fakeSelector";

SEL myRealSelector = (SEL)NSSelectorFromString(@"myMethodIsJustString");

SEL myCStringSelector = (SEL)"myCStringSelector";

SEL myFakeSelector = (SEL)someObj;

return 0;

} We will get the following output in the debugger as a result (pay attention to the values of our variables):

But this is the topic of another article, which is not related to Objective-C Runtime, but to development in C, representing data in memory and using debuggers.