The course of lectures "Startup". Peter Thiel. Stanford 2012. Lesson 10

- Transfer

- Tutorial

In the spring of 2012, Peter Thiel ( Peter Thiel ), one of the founders of PayPal and the first investor FaceBook, held a course at Stanford - "Startup". Before starting, Thiel stated: “If I do my job correctly, this will be the last subject that you will have to study.”

One of the students of the lecture recorded and posted the transcript . In this habratopika, I am translating the tenth lesson.

Lesson 1: Challenging the Future

Lesson 2: Again in 1999?

Session 3: Value Systems

Session 4: Advantage of the last move

Session 5: Mafia Mechanics

Session 6: The Law of Thiel

Session 7: Follow the money

Session 8: Presentation of an idea (pitch)

Session 9: Everything is ready, but will they come?

Session 10: After Web 2.0

Session 11: Secrets

Session 12: War and Peace

Session 13: You Are Not a Lottery Ticket

Session 14: Ecology as a Worldview

Session 15: Back to the Future

Session 16: Understanding Yourself

Session 17: Deep Thoughts

Session 18: Founder - Victim or God.

Occupation 19: Stagnation or Singularity?

After Web 2.0

Mark Andressen, co-founder and senior partner of venture investment company Andreessen Horowitz, joined the lesson as a guest. All thanks for the good material to him and Peter. I tried to be precise, but keep in mind - this is not a verbatim transcript.

I. Hello World

It all started about 40 years ago with ARPANET. Everything was asynchronous, speeds were low. Entering online, in fact, began in 1979 with the introduction of the CompuServe model. In the early 80s, AOL joined, realizing a closed model of services, offering games, chats, etc. Having laid the foundations of the modern web, the two companies merged in 97th.

The Mosaic browser began to be developed in 1993. Netscape announced it on October 13, 1994, and less than a year later entered the IPO. From this began the World Wide Web, which in many ways defined the 90s.

“Web 1.0” and “2.0” are terms that are difficult to define accurately. Speaking about the transition from 1.0 to 2.0, we mainly mean the changes that occurred during the change of the decade. When it all started, the content was mostly static. Now the main emphasis is on data created by users, social networks and collaboration in one form or another.

There have been changes in the patterns of using the network. In the early 90s, people used FTP. In the late 90s, web access or p2p connections were mainly used. In 2010, the network was more than half used for video transmission. These rapid changes inevitably raise the question of what will happen next. Will the next era be a shift towards mobile devices, as many think? It sounds convincing, there are many perspectives. But it is worth considering that in itself this relative shift does not show the whole picture. The overall use of the Internet has increased significantly. Now, about 20 times more users than it was in the late 90's. The ubiquity of the network has made a big difference.

II Wild West

In the past 20 years, the Internet has been very similar to the Wild West. It was a front line, a kind of huge open space, where people could do almost anything. By and large, there were no strict rules and restrictions. You can bet it is good or not. There are some interesting questions. What made it possible to become the Internet as it is? Is the ghost of regulation hanging over us? Should everything change?

The last 40 years, even more, the ordinary world has been quite strictly regulated. The world of bits and bytes was regulated much less. It is unlikely that anyone will be surprised that the world of bits - computers and finance - has been the best place for the last 40 years. These sectors have been extremely innovative. In fact, finances were probably even too innovative. Regulators took note of this, and now, there, probably, you will not really turn around. But what about computers? Should we expect more innovations in the future or less?

Some fairly large events in the world of the development of the Internet fall into everyone’s field of vision. Everyone has heard about the recent high-profile debate about things like PIPA and SOPA. But other changes can be just as dangerous, but less obvious. A patent system, for example, is really worth worrying about. Software patents create many limitations for small companies. No one can close you just because you are small. But that’s exactly what patents do. Large economies of scale can afford to either pay for patents or circumvent restrictions.

III When will the future come?

No one knows exactly when the future will come. But there is no reason not to think about it. Of course, you can find many examples when the seers painted the future significantly different from what happened in the end. Knowing how and why something didn't happen as people predicted is very important. If you hope to achieve something, you must understand how it happened that people who were “in your place” failed. Instead, we somehow tend to completely ignore thoughts about the future.

Predictions by Villemard (1910) about what the school will be like in 2000. Lessons will be digitally downloaded to children in the brain, but there is still a teacher. There are still desks. And the car is powered by a handle.

Just a few decades ago, people predicted chemical food and home heating on radium. The errors of predicting the future are nothing new. In 1895, Lord Kelvin stated that "the creation of an aircraft heavier than air is impossible." US Patent Commissioner Charles H. Duell was convinced in 1899 that "everything that can be invented is already invented." All of this, of course, was a mistake.

Sometimes the "bad predictors" were extremely optimistic. In the 60s, people thought that soon everything would run on nuclear fuel. We will have flying cities. Why some predictions did not come true is an interesting question. But even more interesting are the cases when people were right about the future, making mistakes only in time. Many times, people came to the right conclusion, but it took more time to advance.

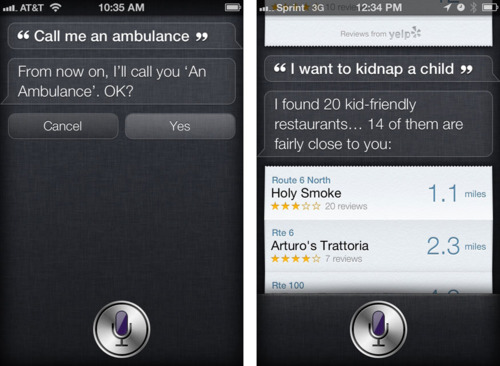

These are examples in which the AI is still not working.

Translation of inscriptions on the smartphone screen

Phone : From now on, call you "Ambulance"?

(Puns: “Call me an ambulance” by ear can be understood as “call me Anna Ambulance”)

Phone : Found 20 restaurants where you can come with children. 14 of them are in your immediate vicinity. OK?

Left screen

Man : Call me an ambulance.Phone : From now on, call you "Ambulance"?

(Puns: “Call me an ambulance” by ear can be understood as “call me Anna Ambulance”)

Right screen

Man : I want to abduct a child.Phone : Found 20 restaurants where you can come with children. 14 of them are in your immediate vicinity. OK?

Take a look at mobile technology. People have invested in this area for many years. Mostly too soon. All who were involved in mobile systems before 99 failed. No one thought that the best investment in mobile technology would be the purchase of Apple shares.

There are many more similar examples. The first rockets were invented in China in the 13th century. But it was too early to try to fly to the moon. Flying there was a good idea - you just had to wait a few hundred years. Apple created the Newton mobile device back in 1993, but it took another 15 years to come to the iPhone. Napster first appeared. It was too early for him, and he probably violated too many rules. And now we have Spotify. If we draw the right conclusions, the future that has not arrived will be able to return from the past and put into practice.

IV. Does the software eat the world?

The most famous saying of Marc Andreessen (Marc Andreessen): "software eats the world." Of course, there are a certain number of areas that are already eaten. Telephone directories, journalism, brokerage are some examples. It is likely that the music will be eaten too, now distribution for the most part is online. Industry players do not always see when this happens, and do not always accept when it happened. In 2002, The New York Times stated that the Internet has exhausted itself, all this is just a distraction to the side, and we must return and continue to enjoy print newspapers. The record industry was jubilant when Napster was defeated. The celebration was premature.

If it is true that software engulfs the world, a reasonable question arises: what else is absorbed or will be eaten in the future. There are several candidates. A lot of things are going on in the healthcare field. Many significant improvements in the field of electromagnetic radiation technology, medical analysis and general openness of the field. But there are still many unresolved issues related to regulation and bureaucracy. Education is another candidate to eat. People are trying in every possible way to computerize and automate the learning process. There is also a lab sector in which startups such as Uber and Taskrabbit bypass traditional adjustable models. Another promising area is jurisprudence. Ultimately, computers could replace people in providing most legal services.

It is difficult to say when these areas will be absorbed. It is enough that you should not bet against computers in these areas. It might not be a good idea to become a doctor or a lawyer, as technology can change everything beyond recognition.

In the more distant future, there is another group of candidates ready to replace technology. Media and space / transportation are two examples. Biology should be transformed from experimental science to information science. In the field of intellectual labor and public administration, there is still room for software maneuver. This may still be far, but there is definitely something to improve there.

How should industry sectors and opportunities be evaluated if programs truly eat the world? Consider a 2x2 matrix. In the vertical axis there are two options: compete with computers, cooperate with computers. In essence, this is an anti-technological and technological view. On the horizontal axis, you have 2 options: compete with China or cooperate with China. Antiglobalization and proglobalization.

On the axis of globalization, it is probably better to collaborate. It's too hard to compete. People will never make money this way. They will beat each other until the blood passes. Do not compete with China, even if you can win. It will be a Pyrrhic victory.

Similarly with the technological axis, it will probably be wise to avoid competition. Even if you can extract square roots faster than computers, which was quite realistic a few decades ago, you should not compete with them. Computers will catch up and overtake you. The chess confrontation between a man and a computer ended badly for a man back in 1997.

Returning to the axis of globalization, where we stopped on cooperation with China, I want to note. Collaboration is better than competition, but maybe this is not the area that needs to be addressed. Too many people are now working with China. In this sense, cooperation with China may be too competitive. Almost everyone is now focused on globalization instead of technology.

This completes the indirect proof: it remains only to cooperate with computers. Of course, indirect evidence is deceptive enough. Everything seems to be pointing in the same direction, but the direction may be wrong. When you change the point of view or entry, the direction may change to the opposite. But circumstantial evidence is still a useful tool. If it seems that nothing else works, you need to use what is.

V. Conversation with Mark Andressen

Peter Thiel : Mark, you've been in the high-tech industry for two decades. How did you imagine the future in 1992? In 2002? Now?

Mark Andressen: My colleagues and I created Mosaic in 1992. It is difficult to overestimate the controversy of this undertaking at that time. Belief in the very idea of the Internet was then rather the exception. At that time, the “information superhighway” was the dominant metaphor. People saw the advantage of additional information. In a way, we got 500 TV channels instead of 3. But the idea of interactive television seemed much better than just more TV channels. This seemed to be the next “big shift." Key media industry leaders were fully involved in ITV. Bill Gates, Larry Ellison, everyone believed that interactive television was the future. Large companies would have to (continue) to prevail. Oracle (Oracle) would develop interactive software for TV, and the information superhighway, on the contrary, should remain passive. He was not supposed to be anything special from the old traditional media. In 1992, the Internet was as muddy, obscure, and academic as it had been since 1968.

Honestly, in 1992 it was still deaf. Most of the huge skepticism about the Internet seemed justified. All you needed to log in was to have a degree in computer science. Everything had to develop slowly. But clinging to this skepticism and not engaging in new developments was probably not worth it. Larry Alison said in 1995 that the Internet would go nowhere because development is too slow. This was puzzling, since theoretically the Internet could be connected via the same wires that have already been routed to people's homes. Modems worked quite well. In fact, the root cause of prejudice against the Internet was the same as it is today. People fear the Internet because it is unregulated, decentralized, and anonymous. He looks like the Wild West. But people do not like the Wild West. People are not comfortable. Therefore, it was very controversial in 1992 to claim that the Internet would be the next “big shift."

Everything depended as much on the path itself. The tech fanatics who popularized the web were neither oracles nor prophets and had no access to the Absolute Truth. Honestly, if we had access to large power structures and could easily go to Oracle, many of us would have failed. But we were just tech fanatics who didn't have that kind of access. So we just made a web browser.

Peter Thiel : What did you think would actually happen to the Internet?

Mark Andressen: We were greatly helped by the fact that we saw how it all works in computer research universities. In 1991-92, a high-speed 45-megabit connection with a campus worked in Illinois. We had modern workstations with a network connection. Streaming video and real-time collaboration worked. All students had an email. All this was simply limited to the borders of the university. When you graduated, it was assumed that you would simply stop using mail. This could have lasted a long time, and it immediately became obvious that all these things should not remain only in research universities.

And then it worked. Mosaic was released at the end of 92, at the beginning of 93. It was launched in the 93rd. Then there was a classic exponential growth. The mailboxes to which incoming licensing requests should have arrived were completely clogged. And at some point only a fool could not notice that this is the same big shift.

Peter Thiel : Did you think in the 90s that the future would come faster than it actually came.

Mark Andressen: Yes. And there is a great deal of irony in the fact that the ideas of the 90s were mostly true. It was only too early. We all thought that the future would come very soon. And a lot of this was a failure. Only now all those ideas come to life. Time is everything. But it is also the hardest to control. Difficult, as entrepreneurs are innately too energetic to wait. It’s also worth noting that “too early” is even worse for an entrepreneur than to make a mistake in choosing a direction. It is very difficult to just sit and wait until the time comes. It almost never works. You will run out of capital. By the time the “right” time arrives, your architecture is already aging. You destroy the company culture.

Peter Thiel: In the early and mid-2000s (2000-2010), people were very pessimistic about the ideas of the 90s. Is it the same now?

Mark Andressen : There are two types of people: those who experienced the crisis of 2000, and those who did not. Those who experienced left deep psychological scars. They were irrevocably affected. These are people who like to talk about bubbles. Always and everywhere they have to find a bubble. They are now 30, 40 or 50 years old. And they are scorched from the inside. If they are journalists now, they describe the massacre. If they are investors, they suffer terribly. If they are ordinary workers, they gain worthless stocks. They promised themselves that they would never burn out again. And now, 12 years later, they are still determined to fulfill the promise.

All these scars do not go anywhere, although they should have already gone. People who survived the crash of 1929 never again believed in the securities market. The market actually began to grow only after the generation of professional investors changed. Now we are somewhere in the middle of the generational change after the collapse of the dotcoms.

This is good news for students and young entrepreneurs. They missed the events of the late 90s, and therefore, at least in relation to this crisis, are in good psychological shape. When I once mentioned Netscape in a conversation with Mark Zuckerberg. He asked: “What else did Netscape do?” - I was shocked, but he looked at me and said: “Buddy, I was in grade 7 then, I did not pay attention to it.” And that’s good. Entrepreneurs from 20 to 30 in good shape. But the people who went through the crisis are not so lucky. Most have scars.

Peter Thiel : You claimed that software eats up the world. Tell us how this will happen in the next 10 years.

Mark Andressen: There are three development options: weak, strong and very strong.

The basic, weak version is that the software will eat up the tech / computer industry. The value of computers increasingly lies in software, not in hardware. The shift to cloud computing is proof of this. It was a transition to larger, less expensive models where software is key. All this is very different from the old model.

In a “strong” version of development, software will eat many other areas of industry that have not yet been the subject of rapid technological change. Take, for example, newspapers. Newspaper production has not undergone significant technological changes for about 500 years! Production has been about the same since the 15th century - and then all of a sudden - bang! There was a digital revolution, and industry was forced to adapt and change.

In the most powerful version, companies, in the likeness of Silicon Valley software companies, will be consumed by everyone. The companies of the type that we create in the Valley will become dominant in almost all areas of industry. These companies are core software companies. They know how to develop software. They understand the economics of software. They put design and development in the first place - that's why they win.

All this is reflected in the theses of the company Andreessen Horowitz. We are not engaged in treatment technologies or biotechnologies. We undertake only what is based on software. If the software is the heart of the company, if everything shatters in the event of the dismissal of a team of key developers - excellent. Companies that will dominate most areas of industry are companies with the same set of management practices and characteristics that are used on Facebook or Google. This, of course, will not be easy, and will meet with strong resistance. But dinosaurs are not held in high esteem now, and they are already being crowded out by birds.

Peter Thiel: Are there any areas of industry that are in a subversive state? As you know, bully children are called to the director, and subversive companies like Napster can be destroyed. Is it possible to succeed in open competition, even if you use the Silicon Valley model in other respects?

Mark Andressen: Look at what Spotify does - it's not at all the same as Napster did. Spotify writes a huge amount of checks to owners of music labels. And they accept it. Spotify decided to write checks from the very beginning. They started in Sweden because there was no developed CD market. Yes, they use a disruptive model, but they have found a way to mitigate the explosion. When you start a conversation with the phrase: “so by the way, we have a little money for you here,” things usually go a little better.

They still come under high pressure. They seem to run through the ranks. Finally, it is not yet clear whether all this will work or not. Stakeholders are very nervous. Things can go wrong in a thousand different ways. Both Spotify and Netflix certainly know this. The danger to paying an interested party is that these people can take money and then just kick you out of business. If you play correctly, you will win. If you make a mistake, you will be left with nothing.

Peter Thiel : A little background: Netflix ran into a problem a year ago when content providers raised prices. Spotify tried to protect itself from this by concluding a package of agreements that expire at different times, so that the main players could not unite and at the same time increase prices.

Mark Andressen: And the record companies are trying to counter this by concluding short-term deals, and, in some cases, by getting an “insoluble” share in the share capital. It may happen that in the end they will receive all the money and all the shares. Spotify and Netflix are spectacular companies. But by the very nature of their business, they are forced to flee through the ranks. Basically, you need to use an indirect path wherever possible. If you are forced to compete, try to do it in an indirect way, innovate and perhaps you will be able to get ahead.

Peter Thiel : What areas do you think are most promising in the very near future?

Mark Andressen: Probably retail. We are now witnessing the onset of e-commerce 2.0, e-commerce not only for freaks. Version 1.0 was heavily tied to the search. You went to Amazon or eBay, found the product you need and bought it. This works well if you know exactly what you are looking for. Model 2.0 is associated with a much deeper understanding of consumer behavior. These are companies such as, for example, Warby Parker and Airbnb. Changes capture one food vertical after another. And this will continue in the world of retail, if only because starting a business from retail is bad. Very high fixed costs for maintaining the store and accounting. Margin too low to start with. Only 5-10% can destroy everything. Best Buy, for example, has 2 problems. First, people can buy almost everything online. And secondly,

Peter Thiel : Pet food companies are an example of this paradigm.

Mark Andressen : Yes, now this is not such a bad idea! Amazone bought Diapers.com for $ 450 million. Golfballs.com turned out to be a good business. Even Webvan is back! Regrettably, grocery online companies burned out in the 90s. But now, city after city, they are returning, trying to master new delivery schemes. The market has now grown significantly. In the 90s there were about 50 million people online. Now there are about 2.5 billion. People are accustomed to e-commerce. By default, it is believed that everything can be bought online.

Peter Thiel plays the role of a true hedge fund. Andreessen Horowitz plays the role of a hedge fund. And if someone adheres to a strategy of similarity to a hedge fund, it is necessary to focus on retail in the short term, and e-commerce in the long term.

Peter Thiel : What new perspectives did you have as a venture capitalist that you did not have as an entrepreneur? Do you have any new insights on the other side of the table?

Mark Andressen: A big, almost philosophical difference arose in the issue of time perception. For an entrepreneur, time is a huge risk. You must innovate at the right time. You may be too early. And this is really dangerous, since in fact you made a one-time bet. It is rare that someone establishes the same company 5 years after once having tried and made a mistake over time. Jonathan Abrams made Friendster, but not Facebook.

Everything is different with venture capital. To be in business for 20 years or more, you must use the approach in terms of the structure of the portfolio of projects. Ideas, not one-time bets. If you believe in an idea and are financing a company that has failed, this is probably still a good idea. If anyone wants to do the same after 4 years, this is likely to be a good investment. Most venture capitalists will not go for it. They will be too deeply affected by the previous failure. But a systematic analysis of failures is very important. Take a look at Apple's Newton in the early 90s. Mobile technology has been the core obsession of many advanced venture capitalists in the Valley. But it was still early for 2 decades. But instead of forever abandoning this idea, it made more sense to postpone it temporarily, to wait,

Peter Thiel : When people invest and something doesn't work, the best thing you can do is adjust the course. And when people do not invest and something works, they remain attached to their initial views and tend to be very cynical.

Macr Andressen : Exactly. The more investments we lose, the better we understand what was wrong. (Damn it!)

But seriously - if you think you can re-launch an idea that someone already tried to launch 5-10 years ago and failed - good venture capitalists are open to such undertakings. You just have to be able to prove that the time has come.

Peter Thiel : Is there anything young entrepreneurs need to know that they don’t know?

Mark Andressen: The number one reason we all become entrepreneurs is because we all want to focus on the product — to a lesser extent on everything else. We tend to cultivate and glorify such a mindset in the Valley. We are all crazy about the model of "lean" startups. Design and product are key factors. There are many talented people in this, and it helps to create high-quality companies. But there is a dark side to all this - it creates the feeling that entrepreneurs do not need to deal with such difficult issues as sales and marketing. Many entrepreneurs who create good products simply do not have a good distribution strategy. Even worse, when they insist that they don’t need one or call their distribution strategy: “viral marketing strategy”.

Peter Thiel: We discussed earlier why you should not take it at face value when successful companies say that they did not use sales or marketing. Since this, in itself, is probably just a publicity stunt.

Mark Andressen : We hear all this every time: “We will act in the same way as Salesforce.com - sales people are not needed, because the product sells itself.” This is always puzzling. Salesforce.com has a huge, professional sales team. Andreessen Horowitz is very attractive for those who are versed in sales and marketing.

Peter Thiel: Maybe it is time to rethink our attitude towards integrated sales. People still have scars from the 90s, when businesses led by integrated sales burned out. In the early 2000s, it was very difficult to attract people to business development (BD). But it can be very beneficial. Google made phenomenal BD deals with Yahoo. People usually don’t know how beneficial it was to Google. Google does not like to talk about it, because they want to communicate only about design. Yahoo does not want to talk about this - it’s inconvenient.

Question from the audience : Are there any pitfalls that should be avoided in thinking about the future?

Peter Thiel: You can make mistakes in different ways. It may seem to you that the future is still too far away. So, despite the fact that you have chosen the right area, you may be mistaken in time. Or you can choose the right time, but everyone is already doing the same.

It is like surfing. The goal is to catch a big wave. If you think that a big wave is approaching, you are rowing with all your might. Sometimes it turns out that there is no wave, and this sucks.

But you can't just sit there waiting to make sure there is a wave before you start rowing. So you miss her. You need to start in advance, and then let the wave pick you up. The question is how to recognize that the next big wave is on the way.

It's a difficult question. It’s better to make a rowing mistake and not find a wave, than to start rowing too late and skip the wave. Trying to create another social network now is trying to catch the current wave. You can row with all your might, but you have already missed this wave. Social networks are not the next wave. Thus, the main approach should be the desire to make mistakes, aiming for the future. And again, in the end, you need to strive to learn not to make mistakes at all.

Question from the audience : Are we in some kind of big wave now? Or the waves capture one area after another.

Mark Andressen: One after another. Some industries, such as finance, law and healthcare, have an oligopoly structure, which often has close ties with the government. Banks complain about regulation, but are often protected by it. Citibank’s main advantage is its political instinct and ability to overcome bureaucracy. Thus, there are many industries with complex regulation. It's funny to see which ones are changeable and which aren't. There are huge opportunities in the field of law, for example. It may seem to you that the industry is already ripe, and it may be so. But maybe you still have to wait a couple of decades. In venture capital investing, you can never be sure that someone 22 years old will not appear and prove to everyone that they were wrong.

Question from the audience: How do patents relate to the phenomenon of “software absorption in the world”?

Marc Andressen : The key problem with patents is that patent examiners, after registering a patent, no longer work with it. They simply do not know, and cannot, know what is innovation and what is not. As a result, we are forced to deal with a bunch of patents. As a high-tech company, you have two extreme opposite possibilities: you can spend the rest of your life fighting with patents, or you can spend all your money on payments for using them. None of these extremes are good. You need to find a balance that allows you to think about patents last. At its core, it is a constraining regulatory tax.

Peter Thiel: There are four parties to any trial. Two opposing and two teams of lawyers. Lawyers are almost always afraid to lose. Lawyers from defense almost always try to persuade the client to agree. The question is whether you can achieve something if people are ready to fight to the end, defending their patents, even if they have flaws. Or is it better for you to pay the patent fee? High legal costs will pay off if you have to sue only a few times. The danger lies in the fact that you can fight and win while not receiving a deterrent precedent, and claims will continue to flow. This is the worst.

Mark Andressen: There are such areas of industry - the production of medicines and mechanical equipment, for example - where traditions are fundamental. In the data area there are long-standing, historically established norms of how and what to do. But in the software world, things are changing extremely fast. Large companies used to have a huge patent arsenal to use against small companies. Now they are at war with each other. One gets the feeling that the ultimate end state to which large companies shoot is the state where they do nothing at all. Instead, they should simply add another 10,000 patents each year to their portfolio and receive money from licensing. It would have been nice if all this had not happened, but this is not a problem for startups, that the patent system is broken. Thus, if you have starts, you must break through all this. Find your compromise strategy.

Peter Thiel : In a sense, patent issues can be a good sign. If you need any problems, then these are they. They mean that you are creating something truly valuable. Nobody would sue you if you did not have good technology. Thus, these are exactly the problems that you need, even if you do not want to.

Question from the audience : Has a critical mass of Internet users been reached? Perhaps it is more difficult now to be ahead of time?

Mark Andressen : In general, this is true for the Internet. It’s a little harder to be ahead of time, which, in general, is good. Take a look at Golfballs.com. Everyone who plays golf online today. This is very different from what it was in the 90s, in the era of dialup connections.

With mobile phones, too, is not so simple. Someone says that the smartphone market is collapsing. We now have 50% penetration. Or maybe the market will just have to curl. Now it seems that in 3 years there will be 5 billion smartphones in the world. The days when you can buy some kind of “non-smartphone” phone are probably numbered. Along with this shift, a new set of regulators controlling this area has appeared.

Peter Thiel : The big concern about mobile technology is that in the case of a successful distribution model, it may first be banned, and then Apple and Android will copy it. This is a large market, but it is far from being able to simply turn off the regulators from the outlet.

Mark Andressen: Just recently, Apple has blocked the ability to use Dropbox in all iOS apps. Motivated by the fact that interaction with Dropbox encourages people to make less purchases through the App Store. Not like a strong argument. But this is how to deal with bureaucrats in the city council. Even a large and important company like Dropbox can be stopped by Apple.

Question from the audience : What did you learn about the different types of board, coming from the board at several successful companies?

Mark Andressen: Most importantly, you should try to create a board that can help you. Avoid taking abnormal on the board. This is very similar to marriage. Most people end up in a bad marriage. Board members can be really bad. When something starts to go wrong, it is usually believed that at least something needs to be done. But this “something” is often worse than the problem itself. Often, board members do not see this.

Peter Thiel: If you want a board to be effective, it should be small. Three people - the optimal size. The more people you have, the worse you will have coordination. If you want your board to be able to do nothing, make it huge. Non-profit organizations, for example, sometimes have up to 50 people on the board. This brings incredible profits to some pseudo-dictatorial person who runs this nonprofit organization. A board of this size means the inability to control management. Thus, if for some reason you need an inefficient board, make it very large.

Mark Andressen: I have never encountered problems in the board contesting the results of voting. What problems I just did not encounter, but never problems with voting. The problems we are dealing with either kill the company or are resolved.

It is likely that contract terms and the process are all too often discussed. And not enough attention is paid to people. Startups, like a sausage factory. People like sausage, but no one wants to watch how it is cooked. Even with the most famous startups, the same thing. Crisis follows crisis. Everything is going just awful. You fight forward. Who cares what processes you follow? Or who is there with you in the bunker? Entrepreneurs cannot think about this long enough. As well as they do not have the ability to sufficiently explore their venture capitalists.

Question from the audience: In businesses such as Netflix, things seem to be key such as understanding psychology and customer behavior, rather than any technological innovations. But you said that you like software companies in your core. Is there any contradiction here?

Mark Andressen : These elements are related to each other as “AND”, and not as “OR”. You may have software at the heart of the company. And good marketing with sales. This is the best way. Good software companies have good sales and an excellent engineering culture at the same time.

Ideal if the founder / CEO is product oriented. Sales managers should be engaged in sales. Salesmen do not create a product! In unsuccessfully launched software companies, a product is created focusing on sales. Such companies are quickly turning into consulting companies. If the company was founded by a product-oriented person, he can simply set his own rules. This is why investors often doubtfully invest in companies that have just hired a new CEO. With a small degree of probability, this CEO is focused on creating a product. You can’t just take Pepsi’s marketing director and replace Steve Jobs.

Peter Thiel : Are there any exceptions to this rule? Oracle?

Mark Andressen: Not. Larry Ellison is product oriented. Of course, extremely money-centric, but product oriented. He has always been a CEO. Once he broke his back, doing body surfing. In the hospital ward, he continued to lead his company. He always had number 2 as his assistant, in the likeness of Mark Hurd. There were a great many of them. But Larry always had Cheryl.

Sellers can be very successful in optimizing a company in a 2-4 year period. Andreessen Horowitz's position on this issue is as follows: after the seller replaces the product-oriented CEO, after 2 years - we are fired.

There are exceptions here. Meg Whitman was often criticized while working in late eBay, but before that, she created it, and, in general, did a fantastic job. John Chambers definitely did a good job creating Cisco, even though things got complicated. Jeff Bezos came from a hedge fund. Good leaders come from everywhere.

Even designers become good CEOs - take a look at Airbnb. They created the whole company, thinking in terms of design. Design has become extremely important. The success of Apple did not come thanks to their hardware. It came due to OSX and iOS. Design is at the top of it all. There is a lot of talk about internal hardware beauty, but the press does not print it. The best designers are focused on software, those who understand the device software at a very deep level. And the conversation here is not about superficial aesthetics.

Question from the audience : Web browsers came from the university environment. 10 years later, Google came from Stanford. Are you looking at university research laboratories looking for future successful companies?

Mark Andressen: Of course. We invested in a lot of things that were investigated 5-10 years ago. We are looking at Stanford and MIT research laboratories looking for technologies that could become a product in the next couple of years.

Synthetic biology is one example. She could be the next “big thing." It is based on the creation of biological structures by code. This is shocking to people. Pretty scary thing, agree. But it seems like it works, and will soon be ubiquitous.

Question from the audience : What else is worth knowing about how a good CEO is made?

Mark Andressen: At Andreessen Horowitz, we think that being CEO is a skill acquired through training. This is a controversial moment in the world of venture capitalists. Most of them believe that CEOs appear, so to speak, “fully staffed,” in a box tied with a ribbon directly from the CEO factory. They talk about a “world-class CEO,” who must have a unique look and hairstyle. Do not judge strictly: many very successful venture capitalists have a “no joke CEO” mentality, and maybe they are right. Their success speaks for itself. But there is one argument against the world-class CEO model; neither Microsoft, nor Google, nor Facebook fit into it. The CEOs of these companies were, of course, simply magnificent. But they were also the very product oriented guys, who founded these companies. In truth, the most important companies are created and managed by people who have never been CEO before. They are trained on the spot. This scares venture investors. This is risky. But the gain here can be much greater.

The question is simple: does a person want to learn to be a good CEO? This work is not psychologically suitable for some people. Others really want to learn, and they do it. There is one thing you need to understand - to manage managers is not the same as to manage performers. Management of managers is scalable, management of performers is not. Learn to manage managers, and you are on the right track to CEO. You will need to learn a little about copyright so that you don’t get behind the bars, a little finance to get paid, and a little about sales to sell the product.

But the Valley is infected by the vision of Dilbert: everyone believes that management is a bunch of idiots, and engineers are forced to save the situation in spite of them. This is not true. Management is extremely important. We are trying to get the best results on the power law curve. Try to see good practices and learn from them. The best companies are run by people with good managerial characteristics and a vision of the product.

Question from the audience : What is more interesting: to establish a company, or to be a venture capitalist?

Mark Andressen: These are quite different things. Basically, company founders would not want to be venture capitalists and vice versa. The classic founder / CEO is a person who wants to keep everything under control. He would have hated his job if he had been a venture capitalist, because he could not give direct orders. Instead, the venture capitalist has only indirect influence in his arsenal. But the venture capitalist, most likely, would also not want to be a founder. Venture capitalists have the luxury of expressing their opinion without an obligation to realize it. Implementation for them can be difficult and unpleasant. So different people, depending on their inclinations, may prefer this or that role. I like both, but this is not common.

Question from the audience: What would you advise students (future entrepreneurs): to establish a company with university friends, or go to work in a small (10 people) startup?

Mark Andressen: Starting a company from scratch is hard. Just leaving the student bench is even harder to do this. You should go to a small startup and see how young companies work. But in general there are many ways to learn. Maybe it would be better to go, say, to Facebook or Airbnb and see how the work is going on there, because what you take away here works for sure. It is difficult to be here and give advice - not to establish your company. Andreessen Horowitz picks up the founders right from the school bench. They can be good founders. But for many people, it’s really useful to first see how other companies work.

Peter Thiel: The counterargument to this is that the founders of Google, Microsoft and Facebook did not really have much experience. If you look at very successful companies, you will often come across the fact that their founders before that did not have any such experience at all. The question when we talk about experience is this: what to adopt? How to use it? If you worked in a startup for 10-20 people and failed, maybe you learned here what you don’t need to do. Or maybe he was bent for other reasons, and you did not recognize all the traps. Or you were very scared and could no longer take the risk.

What experience can be learned from working in large companies? The problem is that here, it seems that everything works automatically. It is very difficult to learn startups, working at Microsoft or Google. These are big companies with phenomenal people. But these people founded too few companies. One theory is that these are too protected places, it is very quiet there. They are also too far in process from startups.

It’s better not to think about where to go, but to think about what to do. This is the key question: what do you believe in? What makes sense? What is likely to work? If the revenue of the companies is really subject to the power law, it is important to get into the only company that you think is the best. The question of what stage of development the company is at is less important than the essence of what you will do.

Mark Andressen : In 1991, I was an intern at IBM. That was a complete failure. Those familiar with IBM's history know this period as the era of John Akers. I learned quite well how to destroy a company. I learned all about dysfunctional companies. It was charming. Once I saw an organization chart. The company had 400,000 employees. I was at level 14 of subordination from CEO. Which meant, boss boss boss boss boss boss my boss is 7 levels below CEO.

The experience you learn from IBM is about how to work at IBM. He is absolutely closed. People do not leave there.

From the translator :

I ask for translation errors and spelling in PM.