US National Innovation System

In the conventional wisdom, innovations are technologies emerging from nowhere and turning the world on its head, as was the case with home computers and smartphones. In fact, for any country, they happen thanks to the built-up national innovation system. Innovation is more than science and technology. Similarly, the innovation system is not only the elements of infrastructure directly related to the advancement of science and technology.

The national innovation system includes economic, political and other social institutions that affect innovation - the national financial system, legislation on the registration of enterprises and the protection of intellectual property, the pre-university education system, labor markets, culture, and specially created development institutions.

This article describes the evolution of the US national innovation system from the 19th century.

Stanford University

English economist Christopher Freeman defined the national innovation system as “a network of institutions in the public and private sectors whose activities and interactions initiate, import, modify, and distribute new technologies.” The success of the country in various fields, its competitiveness in the domestic and foreign markets depends on the development of the innovation system. Understanding the origin, development and operation of the national innovation system helps lawmakers and experts identify the strengths and weaknesses of the system, and make changes that increase the efficiency of creating innovations.

Due to many factors, no country’s innovation system is like the others. Each system is unique. These factors are several:

Success requires correct and balanced work with these three components of the “triangle of innovation success”.

The business environment includes the institutions, activities and opportunities of the country's business community, as well as broader social relations and practices that allow innovation.

The factors that determine the efficiency of the business environment include:

The global financial crisis of 2008 showed the consequences of a lack of regulation in certain industries. Therefore, it is not enough to simply abolish all prohibitions for entrepreneurs and relieve them of the tax burden. Regulators must balance the limits, benefits, business opportunities. The regulatory environment is determined by many factors, among which the most important for the national innovation system are:

New entrants introducing their designs and technologies should be able to raise funds, launch an enterprise and enter the market. The development of the innovation environment depends on the policies of the central government:

Now, when we briefly discussed the components of the “triangle of innovation success”, we turn to the history of the formation of the national innovation system of the United States, which began in the second half of the XIX century. This will allow us to better understand how the system works and how it develops.

In the first 125 years of its independence, the United States of America was not a global technology leader. They remained behind the European nations - Great Britain, Germany. The country joined the leaders after the Second Industrial Revolution of the 1890s, starting to create innovations.

The scale of the markets is of paramount importance for innovation and competition. Thanks to its size, the US market allowed entrepreneurs to successfully sell new mass products - chemicals, steel, meat, and later - cars, airplanes and electronics. American DuPont, Ford, General Electric, GM, Kodak, Swift, Standard Oil and other companies took the lead.

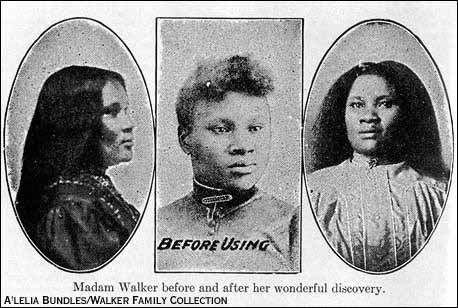

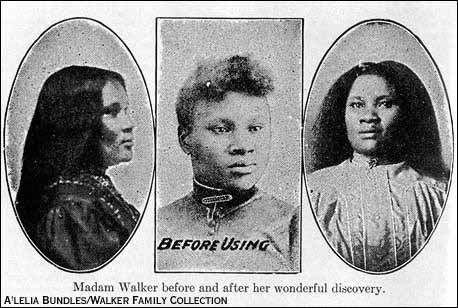

Unlike Europe, which needed to overcome pre-industrial craft-based production systems, Americans easily worked with new forms of industry. An important role was played by culture, in which commercial success was valued above all. In the United States lived the first woman millionaire - Madame C.J. Walker . In a country that did not differ by tolerance to women or people with skin other than white, hundreds of years ago, a millionaire woman appeared, and at the same time, an African-American woman once again speaks of high respect for the entrepreneurial spirit.

Unlike Europe, which needed to overcome pre-industrial craft-based production systems, Americans easily worked with new forms of industry. An important role was played by culture, in which commercial success was valued above all. In the United States lived the first woman millionaire - Madame C.J. Walker . In a country that did not differ by tolerance to women or people with skin other than white, hundreds of years ago, a millionaire woman appeared, and at the same time, an African-American woman once again speaks of high respect for the entrepreneurial spirit.

But it cannot be said that state policy did not play any role. The state, which supported the construction of canals, railways and other internal improvements in the first half of the 19th century, provided entrepreneurs with the opportunity to sell their goods throughout the country. Without developed infrastructure, the market would be different.

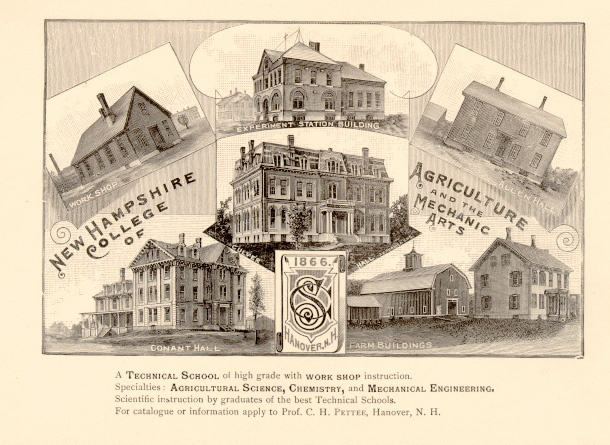

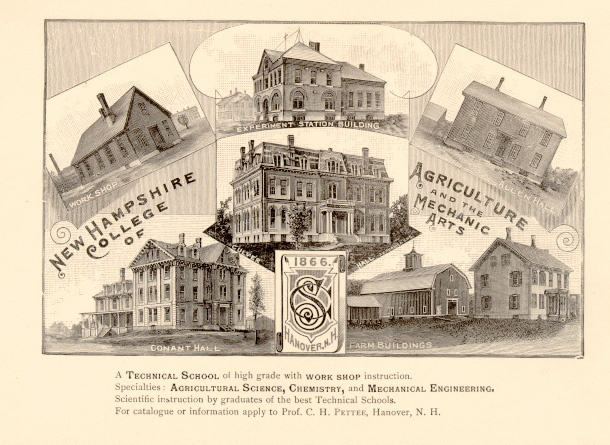

Historically, American research universities go back to the model of public landgrant colleges (land-grantcolleges). In 1862, the Morilla Act was passed in the USA.(Morill Act), according to which land was allocated free of charge for the founding of a college - 30,000 acres each, or 120 sq. Km. in every state. Up to this point, scientists were “free artists,” who sometimes made discoveries. Now, scientific activity in the United States has become regular. The act was also intended to satisfy the need for qualified personnel.

The anti-trust act of Sherman of 1890 became the first antimonopoly law of the USA, which related to the crimes of obstructing the freedom of trade by creating a trust (monopoly) and entering into an agreement with such an aim. Federal prosecutors began to prosecute such criminal associations. The punishment was carried out in the form of fines, confiscations and prison terms of up to 10 years. The Sherman Act is valid now.

Following the Sherman Act in 1914, it was adoptedClayton Antitrust Act governing trusts. They were forbidden to sell goods in the load, as well as sell the same product to different buyers at a different price - this is called " price discrimination ."

Before World War II, most innovations were made by private inventors and private companies. The war spurred the development of industry and stimulated the creation of new technologies in state-based enterprises, as well as in large companies that received orders from federal authorities. During the Great Depression, and then during the war, a number of research laboratories were opened. It promoted innovation in a number of industries, including electronics, pharmaceuticals, and the aerospace industry. Federal support for technology research and development in World War II helped develop the “arsenal of democracy” that the Anti-Hitler coalition used to fight the Axis powers and their allies.

The state continued to play an important role in the innovation system after the war through the financing of the system of national laboratories and research universities. Research funding helped spur innovation and played a key role in ensuring US leadership in a number of industries, including the development of computers and software and biotechnology. Basically, funding went through missionary agencies, or development institutions, seeking to fulfill a specific federal mission — for example, to develop defense technologies, health care, or energy.

Nevertheless, the volume of support for the innovation sphere decreased in the post-war period. Work in this direction in the administrations of the presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon did not have a systemic nature. For the first time after the war, a major attempt to improve the effectiveness of the national innovation system on the part of the federal authorities was made by the Kennedy administration in 1963 - it was a proposal to create a Civilian Industrial Technology Program (CITP).

The CITP initiative was designed to balance development in a country where there was a clear bias towards defense and space technology, which intensified as the United States wanted to confront the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Within the framework of CITP, the state provided funding for university research in sectors useful to civil society: coal mining, housing, the textile industry. Congress rejected the program because of industry opposition. For example, the cement industry opposed this program because it feared that innovation could reduce the need for cement in construction.

Two years later, the Johnson administration submitted a revised program to Congress. The new state program “State Technical Services” (State Technical Services) included funding for university technology centers that were to work with small and medium-sized companies to help them use new technologies more efficiently. The Nixon administration turned this program down on the grounds that it considered it an inappropriate intervention by the state in the economy, but offered its own initiative, the Technology Opportunities Program.) - again aimed at creating technologies for solving social problems, including the development of high-speed rail transport and the treatment of certain diseases. This program was valid until 2004.

The government’s efforts to develop defense and space technology were driven by the need to respond to the Soviet threat, and attempts to support commercial innovations were not guided by any fundamental vision or mission. At that time, they were not related to general economic policies, which focused mainly on fighting poverty and unemployment.

In the late 1970s, there was competition with the United States in the face of countries such as Japan and Germany. With the election of President Jimmy Carter in 1976, the federal government began to take more seriously the advancement of technology, innovation and competitiveness. The motivation for this was a severe downturn in 1974 (the worst since the Great Depression), a shift in the US trade balance from surplus to deficit, and the growing recognition that nations such as France, Germany and Japan now pose a serious challenge to the competitiveness of US industry. It was at that time that the so-called “ rusty belt ” appeared.

Lawmakers responded by passing several laws. In 1980, the law of Stevenson-Weidler " On technological innovation»Demanded that each federal laboratory create an office to identify commercially valuable technologies and their subsequent transfer to the private sector. In the same year, the Bay-Dole Act was passed, which The Economist described as the most successful in the second half of the 20th century, and The Wall Street Journal included the three most effective measures to develop innovation. This law gave universities the opportunity to earn on the results of their research. Prior to the adoption of this law, universities that received funding from the state could not manage the results of research, and in order to buy a patent for private production, it was necessary to spend a lot of time negotiating with sluggish government services.

In 1980, the US government financed 60% of academic studies and owned 28,000 patents, of which 4% were claimed by industry. After the adoption of new laws, the number of patents has increased tenfold over several years. By 1983, at universities, for the commercialization of scientific and technical results, 2,200 firms were organized, in which more than 300,000 jobs appeared. Instead of continuing to absorb budget funds, universities began to generate money for the American economy.

Also in the 1980s, various programs to stimulate innovation appeared: Small Business Innovation Research, Small Business Investment Company-reformed, Small Business Technology Transfer, Manufacturing Extension Partnership. This is a variety of grants for development, research, collaboration with universities. Tax concessions for research and development have been introduced. Thanks to the grants, many new joint research enterprises and scientific and technological centers were created. Another impetus was the US National Medal for Technology and Innovation.- state award “for outstanding contribution to national economic, environmental and social welfare through the development and commercialization of technological products, technological processes and concepts, due to technological innovations and the development of national technological labor”, which receive an average of about eight people or companies in year.

Over the innovation system worked not only the central government. Most of the 50 states contributed to the development of the system. R & D and innovation are the driving force behind the New Economy. The state thrives when it supports research related to the commercialization of technology. For example, under the leadership of Governor Richard Thornburg, Pennsylvania established the Ben Franklin Partnership Program, which provides grants mainly to small and medium-sized enterprises to collaborate with universities of Pennsylvania.

By the beginning of the presidency of Bill Clinton in 1992, the United States already had fewer problems with competitiveness in the global market. Japan was busy with its own problems - the financial bubblein 1986-1991, which was blown away over ten years. Europe was preoccupied with the domestic market. Moreover, with the growth of Silicon Valley as a technological power and the growth of the Internet revolution, and companies such as Apple, Cisco, IBM, Intel, Microsoft and Oracle, America held leading positions in a number of industries. Washington has reduced the amount of policy innovation in industrial innovation and competitiveness.

Soon after, information technology entered a new phase, with more powerful microprocessors, large-scale deployment of fast broadband telecommunications networks and the growth of social networking platforms Web 2.0. Politicians have understood that information technologies have become one of the key factors of growth and competitiveness. The effectiveness of economic policy needed to work properly with IT. The Bush administration has proposed a number of initiatives to stimulate IT innovation, including simplifying Internet connection regulation, freeing radio frequencies for wireless broadband, and transforming government services into e-government.

While IT business flourished, the US had a problem with competitiveness in the industry. In the “zero”, the country lost more than a third of jobs in manufacturing, most of them because of a decline in international competitiveness, and not because of low productivity.

The United States shifted from managing a high-tech trade surplus in 2000 to about a $ 100 billion deficit a decade later. The great recession, or the global financial crisis of 2008 , on the one hand was the result of this loss of competitiveness, and on the other, the cause of further industrial recession.

During the period of work of President Barack Obama, the authorities again turned their attention to innovations in the field of industry. The US needed to fight the strongest rival, China. The presidential administration proposed the creation of a National Network for Manufacturing Innovation . The main idea of the project is to create a network of research institutes in the country designed to develop and commercialize industrial technologies through cooperation between industrial companies, universities and federal government agencies. In 2016, the network consisted of nine institutions, and in 2017 it was planned to open six more. The project was developed following the example of the Fraunhofer Society., founded in 1949 in Germany. About 17 thousand employees of the Company work in 80 scientific organizations, including 59 institutes in 40 cities of Germany, as well as branches and representative offices in the USA, Europe and Asia.

The administration proposed to Congress to increase tax breaks, increase funding for scientific institutions. Patent reform was carried out. Many measures were presented by the congress itself. But most of the laws were not adopted due to the federal budget deficit and the unwillingness to shoulder the tax burden on citizens.

In the next article we will talk about the elements of the national innovation system and the concept of the “triangle of innovation success”: the business environment, the regulatory environment, the innovation environment itself, and the features of each of these elements in the United States.

The national innovation system includes economic, political and other social institutions that affect innovation - the national financial system, legislation on the registration of enterprises and the protection of intellectual property, the pre-university education system, labor markets, culture, and specially created development institutions.

This article describes the evolution of the US national innovation system from the 19th century.

Stanford University

English economist Christopher Freeman defined the national innovation system as “a network of institutions in the public and private sectors whose activities and interactions initiate, import, modify, and distribute new technologies.” The success of the country in various fields, its competitiveness in the domestic and foreign markets depends on the development of the innovation system. Understanding the origin, development and operation of the national innovation system helps lawmakers and experts identify the strengths and weaknesses of the system, and make changes that increase the efficiency of creating innovations.

Due to many factors, no country’s innovation system is like the others. Each system is unique. These factors are several:

- Business environment

- Regulatory environment - legislation in the field of trade, taxes and business.

- The policy applied to the development of the innovation environment.

Success requires correct and balanced work with these three components of the “triangle of innovation success”.

The business environment includes the institutions, activities and opportunities of the country's business community, as well as broader social relations and practices that allow innovation.

The factors that determine the efficiency of the business environment include:

- Level of management skills.

- The effectiveness of the use of information and communication technologies.

- The level of development of private entrepreneurship.

- Availability of capital markets to attract investment, investors willing to take risks.

- Acceptance of innovation by society.

- Cultural component: the desire for cooperation and tolerance for failure.

- State policy to protect domestic business from foreign competitors - both within the country and outside it.

The global financial crisis of 2008 showed the consequences of a lack of regulation in certain industries. Therefore, it is not enough to simply abolish all prohibitions for entrepreneurs and relieve them of the tax burden. Regulators must balance the limits, benefits, business opportunities. The regulatory environment is determined by many factors, among which the most important for the national innovation system are:

- Patent system, protection of intellectual property.

- Requirements for businesses, their discovery and activities.

- Competition in government procurement.

- Taxation system

New entrants introducing their designs and technologies should be able to raise funds, launch an enterprise and enter the market. The development of the innovation environment depends on the policies of the central government:

- Support for development in certain industries.

- Grants and investments from the federal government.

- Optimization of the startup process of high-tech enterprises.

- The development of the scientific community, a network of universities, accelerators.

Now, when we briefly discussed the components of the “triangle of innovation success”, we turn to the history of the formation of the national innovation system of the United States, which began in the second half of the XIX century. This will allow us to better understand how the system works and how it develops.

The main stages of the formation of the American national investment system

In the first 125 years of its independence, the United States of America was not a global technology leader. They remained behind the European nations - Great Britain, Germany. The country joined the leaders after the Second Industrial Revolution of the 1890s, starting to create innovations.

The scale of the markets is of paramount importance for innovation and competition. Thanks to its size, the US market allowed entrepreneurs to successfully sell new mass products - chemicals, steel, meat, and later - cars, airplanes and electronics. American DuPont, Ford, General Electric, GM, Kodak, Swift, Standard Oil and other companies took the lead.

Unlike Europe, which needed to overcome pre-industrial craft-based production systems, Americans easily worked with new forms of industry. An important role was played by culture, in which commercial success was valued above all. In the United States lived the first woman millionaire - Madame C.J. Walker . In a country that did not differ by tolerance to women or people with skin other than white, hundreds of years ago, a millionaire woman appeared, and at the same time, an African-American woman once again speaks of high respect for the entrepreneurial spirit.

Unlike Europe, which needed to overcome pre-industrial craft-based production systems, Americans easily worked with new forms of industry. An important role was played by culture, in which commercial success was valued above all. In the United States lived the first woman millionaire - Madame C.J. Walker . In a country that did not differ by tolerance to women or people with skin other than white, hundreds of years ago, a millionaire woman appeared, and at the same time, an African-American woman once again speaks of high respect for the entrepreneurial spirit.But it cannot be said that state policy did not play any role. The state, which supported the construction of canals, railways and other internal improvements in the first half of the 19th century, provided entrepreneurs with the opportunity to sell their goods throughout the country. Without developed infrastructure, the market would be different.

Historically, American research universities go back to the model of public landgrant colleges (land-grantcolleges). In 1862, the Morilla Act was passed in the USA.(Morill Act), according to which land was allocated free of charge for the founding of a college - 30,000 acres each, or 120 sq. Km. in every state. Up to this point, scientists were “free artists,” who sometimes made discoveries. Now, scientific activity in the United States has become regular. The act was also intended to satisfy the need for qualified personnel.

The anti-trust act of Sherman of 1890 became the first antimonopoly law of the USA, which related to the crimes of obstructing the freedom of trade by creating a trust (monopoly) and entering into an agreement with such an aim. Federal prosecutors began to prosecute such criminal associations. The punishment was carried out in the form of fines, confiscations and prison terms of up to 10 years. The Sherman Act is valid now.

Following the Sherman Act in 1914, it was adoptedClayton Antitrust Act governing trusts. They were forbidden to sell goods in the load, as well as sell the same product to different buyers at a different price - this is called " price discrimination ."

Before World War II, most innovations were made by private inventors and private companies. The war spurred the development of industry and stimulated the creation of new technologies in state-based enterprises, as well as in large companies that received orders from federal authorities. During the Great Depression, and then during the war, a number of research laboratories were opened. It promoted innovation in a number of industries, including electronics, pharmaceuticals, and the aerospace industry. Federal support for technology research and development in World War II helped develop the “arsenal of democracy” that the Anti-Hitler coalition used to fight the Axis powers and their allies.

The state continued to play an important role in the innovation system after the war through the financing of the system of national laboratories and research universities. Research funding helped spur innovation and played a key role in ensuring US leadership in a number of industries, including the development of computers and software and biotechnology. Basically, funding went through missionary agencies, or development institutions, seeking to fulfill a specific federal mission — for example, to develop defense technologies, health care, or energy.

Nevertheless, the volume of support for the innovation sphere decreased in the post-war period. Work in this direction in the administrations of the presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon did not have a systemic nature. For the first time after the war, a major attempt to improve the effectiveness of the national innovation system on the part of the federal authorities was made by the Kennedy administration in 1963 - it was a proposal to create a Civilian Industrial Technology Program (CITP).

The CITP initiative was designed to balance development in a country where there was a clear bias towards defense and space technology, which intensified as the United States wanted to confront the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Within the framework of CITP, the state provided funding for university research in sectors useful to civil society: coal mining, housing, the textile industry. Congress rejected the program because of industry opposition. For example, the cement industry opposed this program because it feared that innovation could reduce the need for cement in construction.

Two years later, the Johnson administration submitted a revised program to Congress. The new state program “State Technical Services” (State Technical Services) included funding for university technology centers that were to work with small and medium-sized companies to help them use new technologies more efficiently. The Nixon administration turned this program down on the grounds that it considered it an inappropriate intervention by the state in the economy, but offered its own initiative, the Technology Opportunities Program.) - again aimed at creating technologies for solving social problems, including the development of high-speed rail transport and the treatment of certain diseases. This program was valid until 2004.

The government’s efforts to develop defense and space technology were driven by the need to respond to the Soviet threat, and attempts to support commercial innovations were not guided by any fundamental vision or mission. At that time, they were not related to general economic policies, which focused mainly on fighting poverty and unemployment.

In the late 1970s, there was competition with the United States in the face of countries such as Japan and Germany. With the election of President Jimmy Carter in 1976, the federal government began to take more seriously the advancement of technology, innovation and competitiveness. The motivation for this was a severe downturn in 1974 (the worst since the Great Depression), a shift in the US trade balance from surplus to deficit, and the growing recognition that nations such as France, Germany and Japan now pose a serious challenge to the competitiveness of US industry. It was at that time that the so-called “ rusty belt ” appeared.

Lawmakers responded by passing several laws. In 1980, the law of Stevenson-Weidler " On technological innovation»Demanded that each federal laboratory create an office to identify commercially valuable technologies and their subsequent transfer to the private sector. In the same year, the Bay-Dole Act was passed, which The Economist described as the most successful in the second half of the 20th century, and The Wall Street Journal included the three most effective measures to develop innovation. This law gave universities the opportunity to earn on the results of their research. Prior to the adoption of this law, universities that received funding from the state could not manage the results of research, and in order to buy a patent for private production, it was necessary to spend a lot of time negotiating with sluggish government services.

In 1980, the US government financed 60% of academic studies and owned 28,000 patents, of which 4% were claimed by industry. After the adoption of new laws, the number of patents has increased tenfold over several years. By 1983, at universities, for the commercialization of scientific and technical results, 2,200 firms were organized, in which more than 300,000 jobs appeared. Instead of continuing to absorb budget funds, universities began to generate money for the American economy.

Also in the 1980s, various programs to stimulate innovation appeared: Small Business Innovation Research, Small Business Investment Company-reformed, Small Business Technology Transfer, Manufacturing Extension Partnership. This is a variety of grants for development, research, collaboration with universities. Tax concessions for research and development have been introduced. Thanks to the grants, many new joint research enterprises and scientific and technological centers were created. Another impetus was the US National Medal for Technology and Innovation.- state award “for outstanding contribution to national economic, environmental and social welfare through the development and commercialization of technological products, technological processes and concepts, due to technological innovations and the development of national technological labor”, which receive an average of about eight people or companies in year.

Over the innovation system worked not only the central government. Most of the 50 states contributed to the development of the system. R & D and innovation are the driving force behind the New Economy. The state thrives when it supports research related to the commercialization of technology. For example, under the leadership of Governor Richard Thornburg, Pennsylvania established the Ben Franklin Partnership Program, which provides grants mainly to small and medium-sized enterprises to collaborate with universities of Pennsylvania.

By the beginning of the presidency of Bill Clinton in 1992, the United States already had fewer problems with competitiveness in the global market. Japan was busy with its own problems - the financial bubblein 1986-1991, which was blown away over ten years. Europe was preoccupied with the domestic market. Moreover, with the growth of Silicon Valley as a technological power and the growth of the Internet revolution, and companies such as Apple, Cisco, IBM, Intel, Microsoft and Oracle, America held leading positions in a number of industries. Washington has reduced the amount of policy innovation in industrial innovation and competitiveness.

Soon after, information technology entered a new phase, with more powerful microprocessors, large-scale deployment of fast broadband telecommunications networks and the growth of social networking platforms Web 2.0. Politicians have understood that information technologies have become one of the key factors of growth and competitiveness. The effectiveness of economic policy needed to work properly with IT. The Bush administration has proposed a number of initiatives to stimulate IT innovation, including simplifying Internet connection regulation, freeing radio frequencies for wireless broadband, and transforming government services into e-government.

While IT business flourished, the US had a problem with competitiveness in the industry. In the “zero”, the country lost more than a third of jobs in manufacturing, most of them because of a decline in international competitiveness, and not because of low productivity.

The United States shifted from managing a high-tech trade surplus in 2000 to about a $ 100 billion deficit a decade later. The great recession, or the global financial crisis of 2008 , on the one hand was the result of this loss of competitiveness, and on the other, the cause of further industrial recession.

During the period of work of President Barack Obama, the authorities again turned their attention to innovations in the field of industry. The US needed to fight the strongest rival, China. The presidential administration proposed the creation of a National Network for Manufacturing Innovation . The main idea of the project is to create a network of research institutes in the country designed to develop and commercialize industrial technologies through cooperation between industrial companies, universities and federal government agencies. In 2016, the network consisted of nine institutions, and in 2017 it was planned to open six more. The project was developed following the example of the Fraunhofer Society., founded in 1949 in Germany. About 17 thousand employees of the Company work in 80 scientific organizations, including 59 institutes in 40 cities of Germany, as well as branches and representative offices in the USA, Europe and Asia.

The administration proposed to Congress to increase tax breaks, increase funding for scientific institutions. Patent reform was carried out. Many measures were presented by the congress itself. But most of the laws were not adopted due to the federal budget deficit and the unwillingness to shoulder the tax burden on citizens.

In the next article we will talk about the elements of the national innovation system and the concept of the “triangle of innovation success”: the business environment, the regulatory environment, the innovation environment itself, and the features of each of these elements in the United States.