The data collected by Voyager-2 still helps scientists explore the solar system.

Uranus, as seen by Voyager 2 in 1986 (source: NASA / JPL-Caltech)

Voyager 2 flew past Uranus 30 years ago, collecting data on this planet and its satellites. The information transmitted by the probe to the ground is still relevant: scientists make discoveries based on this data. Astronomers from the University of Idaho suggest that the gas giant may have two smaller satellites that have so far avoided being discovered by astronomers. The fact is that these two tiny moons can hide in two rings of Uranus, which complicates their detection.

Rob Chancia, a doctoral candidate at this university, discovered something unusual in the Voyager 2 images 30 years ago. As it turned out, the amount of material on the edge of one of the rings, the α ring, changes periodically. In a similar way, the amount of material on the edge of the adjacent ring β also changes.

Uranus occupies an intermediate position in complexity between the more developed system of Saturn's rings and the simple systems of the rings of Jupiter and Neptune. The first nine rings of Uranus were discovered on March 10, 1977 by James Elliot, Edward Dunham and Douglas Mink. After that, four more were discovered: two by Voyager-2 in 1986, two more by the Hubble telescope in 2003-2005.

Almost all rings of Uranus are opaque, and their width is only a few kilometers. The age of the rings of the planet, according to most astronomers, does not exceed 600 million years. The rings themselves, most likely, were formed in the collision of satellites, which previously rotated around the planet. After a large number of collisions, these satellites broke up into ever smaller particles, of which the rings now consist.

Now scientists are aware of the existence of thirteen rings. In order of increasing distance from the planet, the rings are arranged as follows: 1986U2R / ζ, 6, 5, 4, α, β, η, γ, δ, λ, ε, ν, and μ. The minimum radius has a ring 1986U2R / ζ (38 000 km), the maximum - ring μ (approximately 98 000 km). Between the main rings, presumably, there are weak dust ring accumulations and unclosed arcs. The rings are very dark, the Bond albedo for the particles making up these rings does not exceed 2%. Experts believe that the particles consist of water ice with organic inclusions.

According to Chancia, the radio emission reflected from different parts of the ring has different wavelengths. This indicates that the structure of the rings is heterogeneous, something destroys the symmetry. The results of a study of the rings, conducted by Chancia and his colleague Matt Hedman, were published in The Astronomical Journal. Both specialists have long been exploring planetary rings. Previously, they studied the rings of Saturn according to the data transmitted by the Cassini probe. Now scientists have received a grant from NASA for the project to study the rings of Uranus.

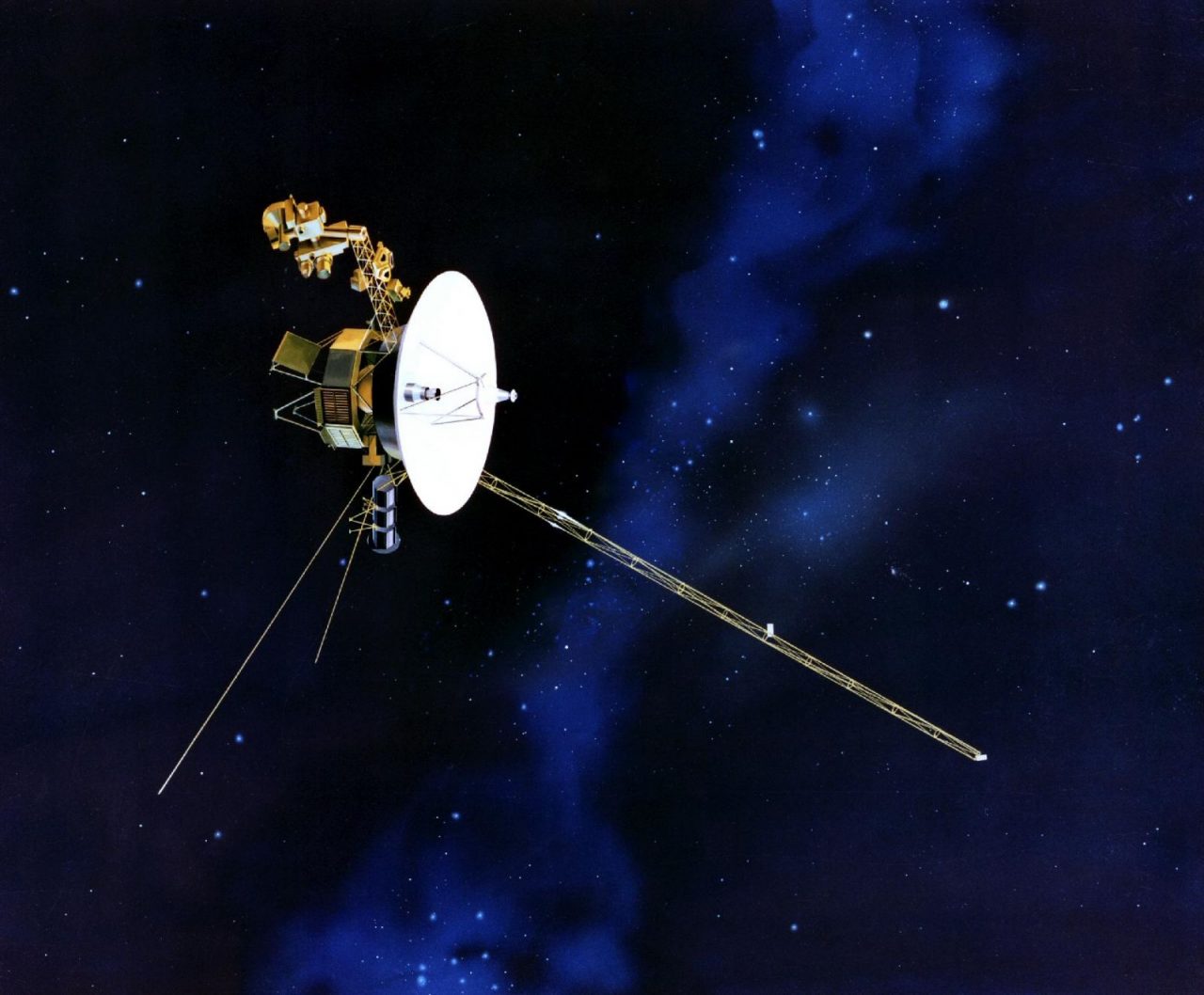

Voyager through the eyes of an artist (source: NASA)

In the study, scientists are assisted by data from Voyager-2, which radiated radio waves 30 years ago in the direction of Uranus rings, which were then received and analyzed on Earth. In addition, Voyager-2 measured the brightness of the stars that were viewed through the rings of Uranus. This method helped determine the approximate amount of material forming the ring.

Similarly, radio waves behave in Saturn's rings. In the rings of this gas giant, which has been studied much better than Uranus, scientists have long since discovered small formations several kilometers in size, which can be considered satellites of this planet. Similar objects, according to the authors of the study, are in the rings of Uranus. Their size, presumably, is from 4 to 14 kilometers. Detecting them with optical instruments is difficult because they are coated with dark material.

“We have not seen these satellites yet, but we think they are small, so they are easy to miss,” says Headman. “Images from Voyager do not allow to see them.”

Scientists believe that the results of their research will help explain some of the parameters of the rings of Uranus. Most of the rings are unusually narrow when compared with the rings of Saturn. Perhaps the miniature satellites of Uranus are helping to contain the expansion of the rings. It is possible that each narrow ring has its own pair of “shepherd satellites”. Initially, this hypothesis was expressed as early as the 70s of the 20th century, immediately after the discovery of the rings in Uranus. Then, when scientists did not find the alleged satellites in the rings in the Voyager-2 images, the hypothesis was considered incorrect. Now it is possible to adopt it again, experts say.

“I will be very pleased to know that miniature satellites of uranium actually exist, and they really solve the problem of the expansion of rings,” says Chancia. Now astronomers continue to study the rings of Uranus, hoping to find answers to other questions regarding this planet.

“It’s very exciting to see that Voyager 2’s historical study of Uranus still helps to explore the planets,” says Ed Stone, one of the participants in the Voyager project.