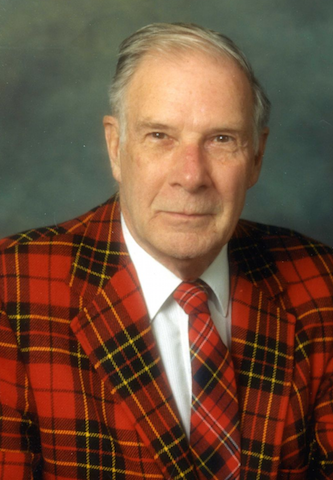

Richard Hamming - the genius of one idea

"If the problem is not solved, try to look at it from a different angle, turning its disadvantage into an advantage."

Richard Wesley Hamming was born in Chicago, Illinois, on February 11, 1915. His father, Richard Hamming, was Dutch-born, participated in the Anglo-Boer War, moved to America, worked as a cowboy, at the time of the birth of his son already held the position of loan manager.

He spent his childhood in Chicago, here he graduated from secondary technical school and the University. Richard Crane Initially, Hamming dreamed of studying engineering, but there was a time of the Great Depression — the world economic crisis, and there was simply no money to study at another higher institution, and at the University. Richard Crane did not teach such discipline. Having chosen the faculty of natural sciences, mathematics, in 1937 he received a bachelor's degree in this discipline. Such a turn of events played a crucial role in the life of Hamming, because as an engineer ... "I would be just a guy who repairs the sewers, and so my life is completely connected with the research work that excites the mind."

Hamming continued his studies at the University of Nebraska. In 1939 he was awarded a master's degree. After that, he entered the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He wrote his doctoral dissertation (on the problems of differential equations with boundary conditions) under the leadership of Valdemar Tryzhinsky, who immigrated to America from Russia in the 1920s and was a professor of mathematics from 1934 to 1969. Richard received a Ph.D. in mathematics in 1942. While still a graduate student, Hamming "discovered" Buhl for himself, read his work "Study of the Laws of Thinking."

In September 1942, Hamming married a classmate, Vande Little, she later received a master's degree in English literature. He lived with her until the end of his days; the couple had no children. In 1944, the scientist became an assistant professor at a university in Louisville, Kentucky, USA (JB Speed Scientific School at the University of Louisville).

In 1945, Richard Hamming participated in the famous Manhattan research project, whose goal was to create an atomic bomb.

Manhattan Project

In early 1943, entire families began to "disappear" throughout North America. Their names were changed, no one knew where they were going, it was impossible to use the train directly, they reached the buses to any other station, and only there they bought train tickets. As a rule, the terminal station was any unknown station, Santa Fe or Albuquerque, after arriving at which, the military machine took the people and ... "no one else saw them in the free world without being accompanied by the military."

Los Alamos did not exist. He was not on the map, he did not have a postal address, its inhabitants simply did not exist. Even phone calls were not allowed.

On June 18, 1942, Colonel James Marshall (James Marshall) was ordered to create an organization that would unite scientists and engineers to work on the development of nuclear weapons. The project received the code name "The Manhattan Project". Simply put, this project was an atomic bomb research and development program. Led by the United States, other countries also took part in the project (Great Britain, Canada). The project manager was Colonel Leslie Richard Groves. For the construction of the complex for the implementation of the program was created Manhattan Engineering District (MED).

The work was carried out in several directions: the study of uranium isotopes, the study of plutonium, the creation of an optimal case for a bomb. Three atomic bombs were created - the plutonium "Gadget", which was detonated during the first nuclear test, the uranium "Kid" (a bomb in the form of a cannonball filled with 235 U), dropped on Hiroshima and the plutonium "Fat man" (more a sophisticated bomb that blew up a sphere or core from plutonium) dropped on Nagasaki. The events in Pearl Harbor accelerated the testing of a new type of weapon.

The forces of the Allies made three plutonium charges, 500 million dollars each. The first charge was used in the Trinity experiment on July 16, 1945, which is considered the beginning of the atomic age. The second charge was blown over Nagasaki, but the third charge, which was planned to be dropped on Japan, was taken to Los Alamos for further research, where he “killed” the scientists themselves and is now known as the “charge-demon”.

Los Alamos 1946

Los Alamos scientists were risky people. In order to determine the critical mass of plutonium nuclei that would be used for the Trinity experiment and the Fat Man bombing, a scientist from Los Alamos, Louis Slotin, developed a procedure that received the marvelous name “dragon twitching by the tail”. According to this "technique", Slotin lowered the beryllium hemisphere onto a plutonium charge ... "beryllium is a neutron reflector, so if you are close enough to the nucleus, the neutrons bounce back to plutonium, causing a supercritical state." Slotin almost completely covered the charge with a beryllium hemisphere, and the only thing that did not allow her to completely cover it was the sting of a flat screwdriver. It turns out that the scientist held a screwdriver with a thin blade and conducted an experiment with it, and this tool! prevented plutonium from gaining critical mass and killing everyone in the room.

Sometimes the screwdriver slid off and the scientist who held it instantly "... was roasted with deadly neutrons." As a result, what happened with Slotin ... The screwdriver slipped out of his hands and the charge of plutonium gained supercritical mass, then emitted a massive explosion of neutron radiation. Slotin managed to turn the beryllium reflector, stopping the chain reaction, but died of radiation after 9 days. And such a terrible incident, alas, was not the only one.

inside the laboratory

The developers of the atomic bomb still realized the enormity of such invented weapons, which can destroy all living things. Interestingly, many project members participated in many peacekeeping organizations, while advocating for general disarmament and peacekeeping.

During World War II, Hamming left Louisville (April 1945) to work on the Manhattan project in the Los Alamos laboratory, went to Hans Bethe's unit, a programming unit for IBM computers that were used for computing performed by physicists. project. His wife, Wanda, soon joined him, and also worked at Los Alamos. Hamming recalled:

“Shortly before the first test, one physicist asked me to check some arithmetic calculations that he did, and I agreed. When I asked what kind of calculations it was, he answered: “This is the likelihood of a bomb being able to“ ignite ”the whole atmosphere.” Hearing the answer, I decided to check these calculations myself! The next day, when he came for an answer, I I tried to explain to him that, “from the side of arithmetic actions, all is true, but I don’t know many physical formulas by which exact calculations can be made.” To which he replied that it was not my business and the only thing that was required of me was to check correctness of mathematical calculations. One thought is not gave me, "What did you do, dear Hamming, you were involved in risky business, which poses a threat to all life in the universe, at the same time you do not understand almost half of what is happening! ”I paced up and down the corridor, my friend came up and asked what excited me so much. I told him about the situation. His answer was: "Nothing, Hamming, no one will ever blame you."

Despite the short period of work at Los Alamos on the project, it was here that Richard Hemming became closely acquainted with computer methods of computational mathematics, which had a dramatic effect on his entire future career and life.

In 1946, Hamming began working with Bell Labs, was accepted into the group of applied mathematicians. Here he worked for almost 30 years, invented and developed many numerical methods for solving scientific and engineering mathematical problems. For a trip to New Jersey, Hamming bought an old car from Klaus Fuchs, who was later exposed by the FBI and declared a spy. Hamming was also called in for questioning.

At Bell Labs, Hamming worked for a long time with Claude Shannon. “We were top-notch riders,” Hamming recalled later, “we unconventionally solved many things and got valuable results. At the same time, the leadership was ready to tolerate us, taking a position of non-intervention. ”

It was at Bell Labs that Richard Hamming, working on the Bell Model V calculating machine, formulated his idea of error correction codes, later called the Hamming code, and published it in 1950 in his only scientific article. The article described the construction of a block code that corrects single errors that occur during message passing. The Bell Model V counting electromechanical machine worked on relay units, the calculation speed was low, data was entered using punched cards, and errors often occurred in the reading process.

One Friday (1947), before going home for the weekend, Hamming asked the car to perform a long, complex series of calculations, but returning on Monday, he discovered that an error had already occurred at the initial stage, and this led to the machine automatically exited the program. All this annoyed the scientist, because he had to work on weekends, often reloading the program. It was necessary to build efficient error correction algorithms, which Hamming did. “If a computer can tell when an error has occurred, then there must be a way to“ force ”it to say exactly where it occurred, and to correct it.”

The codes created by Richard Hamming are self-monitoring, they allow you to automatically detect errors during data transfer. Not a little was written about the codes themselves on this resource, I repeat:

“The Hamming code consists of two parts. The first part encodes the original message, inserting into it in certain places the control bits (calculated in a special way). The second part receives the incoming message and re-calculates the control bits (according to the same algorithm as the first part). If all newly calculated check bits are the same as received, then the message is received without errors. Otherwise, an error message is displayed and, if possible, the error is corrected. "

Hamming code. An example of the algorithm

During the 1950s, he was programming one of the earliest computers, the IBM 650, together with Ruth A. Weiss (Ruth A. Weiss) developed the L2 programming language, one of the earliest computer languages, in 1956 this language was widely used at Bell Labs as well as other users to whom he was known as Bell 2. In 1957, the language was replaced by Fortran, after IBM '650 was replaced by IBM 704.

In 1976, the scientist changed his place of residence and moved to the city of Monterrey, California, here he headed research in the field of computer technology at the Higher Naval School. Here he was engaged in teaching, which he was still seriously interested in in 1960, he wrote books on probability theory and combinatorics. In total, he wrote 9 books, some of which were published many times and in many languages, including 3 in the USSR and about 75 articles. Hamming lectured as a visiting professor at Stanford University, City College of New York, University of California at Irvine, Princeton University.

Hamming's work was marked by many awards, he was the winner of many awards. In the field of artificial intelligence, Hamming’s artificial neural networks, which are used to classify images, are named after him. In many directions (evolutionary modeling) the concept of Hamming distance (the most important concepts of coding theory) is used. In his honor, even a special medal was established, which is awarded to scientists who have made significant contributions to the theory of information.

In 1968, he became an honorary member of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), and was awarded the Turing Award of the Association of Computing Machinery.

In 1979, he was awarded the Emmanuel Piore Prize for his exceptional contribution to the development of information sciences and systems.

In 1980, Richard Hamming was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering Sciences.

In 1981, he received the Harold Pender Award from the University of Pennsylvania.

In 1988, the IEEE Medal of Honor.

In 1996, Hamming was awarded the prestigious Edward Reim Award of $ 130,000 in Munich for his work on error correction codes.

On January 7, 1998, at the age of 82, the heart of the scientist Richard Hamming stopped beating, he had a heart attack.

Richard Hamming was the first to propose a constructive method for constructing codes with redundancy and simple decoding. His work predetermined the direction of most of the work in this area that followed later. His 1950 paper became a kind of catalyst that accelerated the development of coding theory.