Chinese doctors raised new ears for children

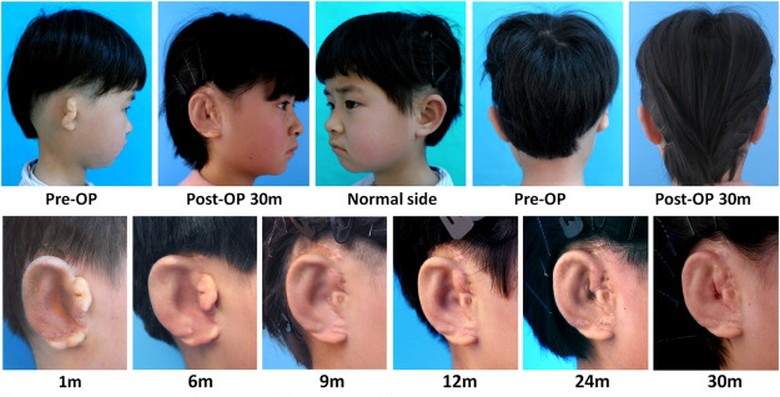

Ear growth after implantation. Before surgery, the microtic area is in the form of peanuts. Two and a half years after implantation, typical features of the auricle appeared, almost symmetrical to a healthy ear.

For the first time in the world, scientists managed to grow full auricles from the patient's own cells. Five Chinese children received one new ear.

Microtia is a congenital malformation of the auricle when it is not sufficiently developed or deformed. Unfortunately, this defect is not so rare: in different regions of the world, the frequency varies from 0.83 to 17.4 per 10,000 newborns. Even if the child has normal hearing, the restoration of the auricle makes sense, because it is an important identification feature of the human face, the authors note a newscientific work from the Shanghai Jiao Tong School of Medicine and the Plastic Surgery Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. In addition, such children cannot wear glasses, often suffer from low self-esteem and psychological disorders.

In this case, Chinese specialists used a technique similar to that used in operations on the famous laboratory mouse Wakanti , on which a human ear was grown on the back in the 90s.

Vacanti mouse

The operation was specifically performed on a naked mouse (Nude), a breed of laboratory mice that has a genetic mutation that manifests itself in underdevelopment or lack of a thymus, which leads to suppression of immune functions. The operation was carried out by a group of doctors from the University of Massachusetts School of Medicine under the direction of Charles Vacanti, also known as Chuck. The results were published in 1997. At one time, this scientific experiment caused serious unrest among activists for protecting the rights of animals and religious groups.

Since then, the experiment has been repeatedly repeated on different animals, but the Chinese colleagues were the first to experiment on humans.

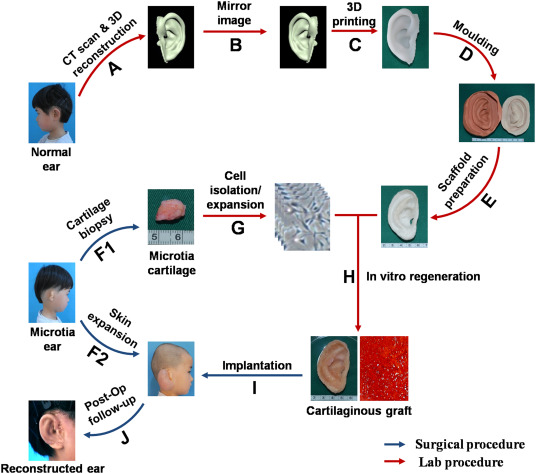

The technique is quite simple (see schematic illustration below). The child has a 3D scan of a healthy ear, then a mirror transformation is performed on the computer, and then a form is printed on the 3D printer. The auricles are formed from biodegradable material, then are populated by the patient’s ear cartilage cells. At the same time, the so-called “tissue expander” is implanted on the microtic site, which frees up space for the future implant from cartilage cells. By the time the latter multiply and fill the mold, a sash forms on the skin near the microtic site, where the workpiece is placed.

Schematic illustration of reconstruction of the auricle from cartilage cells

“This is a very exciting approach,” saysDr. Tessa Hadlock of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. This research institution specializes in research into methods for treating eyes, ears, nasopharynx, head and neck. “They showed that it’s possible to get closer to restoring the structure of the auricle.”

Standard techniques for treating microtia involve the implantation of a synthetic ear or cartilage in the form of an ear taken from the ribs of a child. But both methods have their drawbacks: in the first case, the auricle does not fulfill its function as an organ of hearing, and in the second case, surgery on the ribs of the patient is required. Doctors believe that the new method is simpler and more effective than the existing ones. In addition, it also provides a better look for the ears. True, it remains unknown how long it will take to completely restore the structure of the auricle and what it will take its final shape. Specialists will monitor each of the five patients for five years.

At the moment, the first of five patients who underwent surgery 2.5 years ago, showed a very good result. The remaining four were implanted with cartilage cells later, and the results are also pretty good, although in some of them the auricles are deformed.

A scientific article with the results of clinical trials was published on January 12, 2018 in the journal EBioMedicine (10.1016 / j.ebiom.2018.01.011).