Scientists have created the most advanced digital model of the human face

When computers process faces, they sometimes rely on 3D Morphable Models (3DMMs). The model is an average person and contains information about the general patterns of deviation from this average. For example, if you have a long nose, you may also have a wide chin. Given these correlations, the computer can then characterize your unique face, not storing every point in the 3D scan, and listing only a couple of hundred numbers describing your deviation from the average face, including parameters that roughly correspond to the age, gender and length of the face.

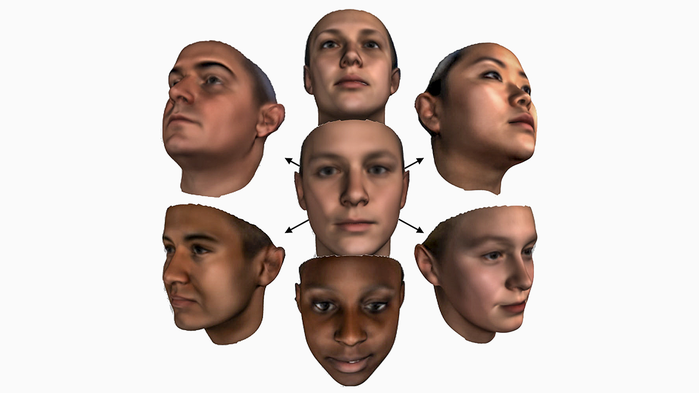

However, there is one difficulty. To take into account all the ways in which a person can change, 3DMM has to integrate information about a large number of faces. Until now, this required scanning a large number of people, and after that - painstaking labeling of all their functions. Therefore, the best modern models are based on the faces of only a few hundred people - mostly white adults - and have limited ability to model faces of people of different ages and races. Imperial College

Computer ResearcherJames Booth and colleagues have developed a new method that automates the creation of 3DMM and allows them to use a wider range of human faces. The method consists of three main steps. First, the algorithm automatically directs a face scan to the tip of the nose and other points. Then another algorithm aligns all scans in accordance with the guidelines and combines them into a model. Next, the algorithm searches for and removes bad scans.

Other researchers have favorably accepted the idea of James Booth. William Smith, a computer science student at York Universityin the UK, who did not participate in the study, noted that the automation of the process of creating models is really a big contribution in this area. Another scientist from the Institute for the Study of Computer Graphics. Fraunhofer in Darmstadt, Alan Brunton said: “Marking dozens of features on a large number of faces is quite tedious. You think that pressing a point is relatively easy, but it’s not always obvious where, for example, the angle of the mouth is. Therefore, even when you do it manually, there is a high probability of making a mistake. "

Booth and his colleagues did not stop there. They appliedhis method to a set of almost 10 thousand demographically diverse face scans. Scanning was done at a science museum in London, by plastic surgeons Allan Ponniah and David Dunaway, who hope to improve recovery operations. They turned to Stefanos Zafeiriou, a computer researcher at Imperial College London, for help in analyzing the data.

Applying the algorithm to these scans has led to the creation of what they call the “large scale facial model (LSFM)." According to the authors, in tests against existing models LSFM depicts faces much more accurately. In one comparison, they created a model of a child’s face from a photograph. When using LSFM, the model really looked like a child. Using one of the most popular models, which is completely based on the faces of adults, the face of the child predictably looked like the face of an adult.

The team of scientists had enough scans to create more specific modifiable models for different races and ages. Their model can automatically classify individuals in age groups by shape.

Booth and other researchers have already worked on a new model. In another experiment, they used 100,000 faces synthesized by their LSFMs to train an artificial intelligence program to turn 2D images into accurate 3D models. This method can be used to verify the identity of a person suspected of having committed a crime using a camera picture, even if it is taken at an angle. In addition, using this algorithm, historical figures recreated from portraits can be embodied and revived.

Soon, LSFM-based medical applications may appear. If someone has lost their nose, technologists can help plastic surgeons determine how a new one should look, given the rest of the face. A face scan can be used to identify possible genetic diseases, such as Williams syndrome, a condition associated with heart problems, developmental delays, and facial features such as a short nose and a wide mouth. The model of Booth and colleagues can increase the sensitivity of such tests. The next step is to include facial expressions in the model that allow you to recognize faces with grimaces or smiles.