Tests on C without SMS and registration

Recently, zerocost has written an interesting article “Tests in C ++ without macros and dynamic memory” , which deals with a minimalist framework for testing C ++ code. The author (almost) managed to avoid using macros for registering tests, however, instead of them, “magic” patterns appeared in the code, which personally seem to me, I'm sorry, inconceivably ugly. After reading the article, I had a vague feeling of dissatisfaction, since I knew that I could do better. I could not immediately remember where, but I definitely saw the test code, which does not contain a single extra character for their registration:

Recently, zerocost has written an interesting article “Tests in C ++ without macros and dynamic memory” , which deals with a minimalist framework for testing C ++ code. The author (almost) managed to avoid using macros for registering tests, however, instead of them, “magic” patterns appeared in the code, which personally seem to me, I'm sorry, inconceivably ugly. After reading the article, I had a vague feeling of dissatisfaction, since I knew that I could do better. I could not immediately remember where, but I definitely saw the test code, which does not contain a single extra character for their registration:

voidtest_object_addition(){

ensure_equals("2 + 2 = ?", 2 + 2, 4);

}Finally, I remembered that this framework is called Cutter and it uses in its own way a brilliant way to identify test functions.

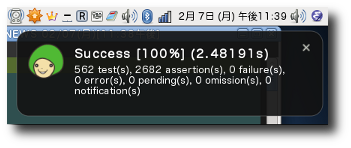

(KDPV is taken from the Cutter website under CC BY-SA.)

What is the trick?

The test code is collected in a separate shared library. Test functions are extracted from exported library symbols and are identified by name. Tests are performed by a special external utility. Sapienti sat.

$ cat test_addition.c

#include<cutter.h>voidtest_addition(){

cut_assert_equal_int(2 + 2, 5);

}$ cc -shared -o test_addition.so \

-I/usr/include/cutter -lcutter \

test_addition.c$ cutter .

F

=========================================================================

Failure: test_addition

<2 + 2 == 5>

expected: <4>

actual: <5>

test_addition.c:5: void test_addition(): cut_assert_equal_int(2 + 2, 5, )

=========================================================================

Finished in 0.000943 seconds (total: 0.000615 seconds)

1 test(s), 0 assertion(s), 1 failure(s), 0 error(s), 0 pending(s),

0 omission(s), 0 notification(s)

0% passedHere is an example from the Cutter documentation . You can safely skip everything related to Autotools, and look only at the code. The framework is a bit strange, yes, like everything Japanese.

I will not analyze the implementation features in too much detail. I also do not have a full-fledged (and even at least a draft) code, as I personally don’t really need it (everything in Rust is out of the box). However, for interested people this can be a good exercise.

Details and possibilities of implementation

Consider some of the tasks that need to be solved when writing a framework for testing using the Cutter approach.

Getting exported functions

To begin with, it is necessary to somehow get to the test functions. Standard C ++, of course, does not describe shared libraries at all. Windows has recently acquired a Linux subsystem, which allows all three major operating systems to be reduced to POSIX. As is known, the POSIX-systems provide the functions dlopen(), dlsym(), dlclose()with which you can get the address of the function, knowing her character name, and ... in general everything. POSIX does not disclose the list of functions contained in the loaded library.

Unfortunately (although, rather, fortunately), there is no standard, portable way to detect all the functions exported from a library. Perhaps, the fact that not on all platforms (read: embedded) in general exists the concept of a library . But that's not the point. The main thing that you have to use platform-specific features.

As an initial approximation, you can simply call the utility nm :

$ cat test.cpp

voidtest_object_addition(){

}$ clang -shared test.cpp$ nm -gj ./a.out

__Z20test_object_additionv

dyld_stub_binderparse its output and use dlsym().

For deeper introspection, libraries like libelf , libMachO , pe-parse will be useful , allowing you to programmatically parse executable files and libraries of platforms you are interested in. In fact, nm and the company just use them.

Filtering Test Functions

As you can see, the libraries contain some strange symbols:

__Z20test_object_additionv

dyld_stub_binderWhat is this __Z20test_object_additionv, when we called a function simply test_object_addition? And what is this left dyld_stub_binder?

“Unnecessary” characters __Z20...are the so-called name decoration (name mangling). Feature compilation C + +, nothing can be done, live with it. This is how functions are called in terms of system (s dlsym()). In order to show them to a person in a normal way, you can use libraries like libdemangle . Of course, the library you need depends on the compiler you are using, but the decorating format is usually the same within the platform.

As for the strange features like dyld_stub_binder, then this is also the features of the platform, which will have to be taken into account. You do not need to call some functions when running tests, as there is no fish there.

A logical continuation of this idea will be the filtering function by name. For example, you can run only functions with testin the name. Or just functions from the namespace tests. And also use nested namespaces to group tests. There is no limit to your imagination.

Passing the context of the executable test

Object files with tests are collected in a shared library, the execution of which code is fully controlled by an external utility driver cutterfor Cutter. Accordingly, internal test functions can use this.

For example, the context of the executable test ( IRuntimein the source article) can be easily passed through a global (thread-local) variable. The driver is responsible for controlling and passing the context.

In this case, the test functions do not require arguments, but retain all the advanced features, such as the arbitrary naming of the tested cases:

voidtest_vector_add_element(){

testing::description("vector size grows after push_back()");

}The function description()accesses the conditional IRuntimethrough a global variable and thus can pass a human comment to the framework. The security of using global context is guaranteed by the framework and is not the responsibility of the test writer.

With this approach, the code will have less noise with the transfer of context to the comparison statements and internal test functions that may need to be called from the main one.

Constructors and destructors

Since the execution of tests is fully controlled by the driver, it can execute additional code around the tests.

The Cutter library uses the following functions for this:

cut_setup()- before each individual doughcut_teardown()- after each individual testcut_startup()- before running all testscut_shutdown()- after completion of all tests

These functions are called only if defined in the test file. They can be placed in the preparation and cleaning of the test environment (fixture): the creation of the necessary temporary files, the complex configuration of the test objects, and other testing antipatterns.

For C ++ it is possible to come up with a more idiomatic interface:

- more object oriented and type safe

- with better support for the RAII concept

- using lambda for deferred performance

- enabling test execution context

But I still think again about this all in detail now.

Self-contained executable test files

Cutter for convenience uses the shared library approach. Various tests are compiled into a set of libraries that a separate test utility finds and executes. Naturally, if you wish, you can embed the entire test driver code directly into an executable file, getting familiar separate files. However, this will require collaboration with the build system in order to organize the layout of these executable files in the right way: without cutting out “unused” functions, with the right dependencies, etc.

Other

Cutter and other frameworks also have many other useful tools that can make life easier when writing tests:

- flexible and expandable test statements

- building and retrieving test data from files

- study of stektraisov, handling exceptions and falls

- customizable crash levels of tests

- running tests in multiple processes

It is worth looking back at existing frameworks while writing your bike. UX is a much deeper topic.

Conclusion

The approach used by the Cutter framework allows for the identification of test functions with minimal cognitive load on the programmer: just write test functions and that's it. The code does not require the use of any special templates and macros, which increases its readability.

The features of building and running tests can be hidden in reusable modules for build systems like Makefile, CMake, etc. The questions of a separate test build will still have to be asked one way or another.

Among the shortcomings of this approach, we can note the difficulty of placing the tests in the same file (the same translation unit) as the main code. Unfortunately, in this case, without additional hints, it is no longer possible to figure out which functions need to be run and which ones are not. Fortunately, in C ++ it is customary to spread tests and implementation into different files.

As for the final deliverance from macros, it seems to me that it is not worth giving up on them in principle . Macros allow, for example, to more briefly write comparison statements, avoiding code duplication:

voidtest_object_addition(){

ensure_equals(2 + 2, 5);

}but at the same time maintaining the same information content of the issue in case of errors:

Failure: test_object_addition

<ensure_equals(2 + 2, 5)>

expected: <5>

actual: <4>

test.c:5: test_object_addition()The name of the function being tested, the file name and the line number of the beginning of the function can in theory be extracted from the debug information contained in the library being assembled. The expected and actual value of the compared expressions are known functions ensure_equals(). The macro allows to “restore” the original writing of the test statement, from which it is more clear why the value is expected 4.

However, this is an amateur. Does the advantage of macros for test code end there? I have not really thought about this moment yet, which can be a good field for furtherperversionsresearch. A much more interesting question: is it possible to somehow make a mock framework for C ++ without macros?

The attentive reader also noted that there are no SMS and asbestos in the implementation, which is a definite plus for the ecology and the economy of the Earth.