Work with Dunno - read-ahead technologies and hybrid storage

One of the ways to improve performance and reduce latency in storage systems (DSS) is to use algorithms that analyze incoming traffic.

On the one hand, it seems that the requests to the storage system are highly dependent on the user and, accordingly, are little predictable, but in reality this is not so.

The morning of almost any person is the same: we wake up, dress, wash, have breakfast, go to work. The working day, depending on the profession, is different for everyone. Also, the storage load is the same every day, but the working day depends on where the storage is used and what is its typical load (workload).

In order to visualize our ideas, we used the images of characters from children's stories about Nikolai Nosov. In this article, the main characters will be Dunno (random reading) and Znayka (sequential reading).

Random read (random read) - Dunno . Nobody wants to deal with Dunno. His behavior defies logic. Although some algorithms still try to predict its behavior, for example, sophisticated algorithms of proactive sampling from memory like C-Miner (more about it will be described below). These are machine learning algorithms - which means that they are demanding on storage resources and are not always successful, but due to the tremendous development of computing power of processors, more and more will be used in the future.

If only Dunno comes to storage, then the best solution would be storage based on SSD (All-Flash Storage).

Sequential reading (Sequential read) - Znayka . Strict, pedantic and predictable. Thanks to this behavior, he can be considered the best friend for storage. There are read ahead algorithms that can work well with Znayka, they pre-place the necessary data in RAM, minimizing the latency of the request.

Blender effect

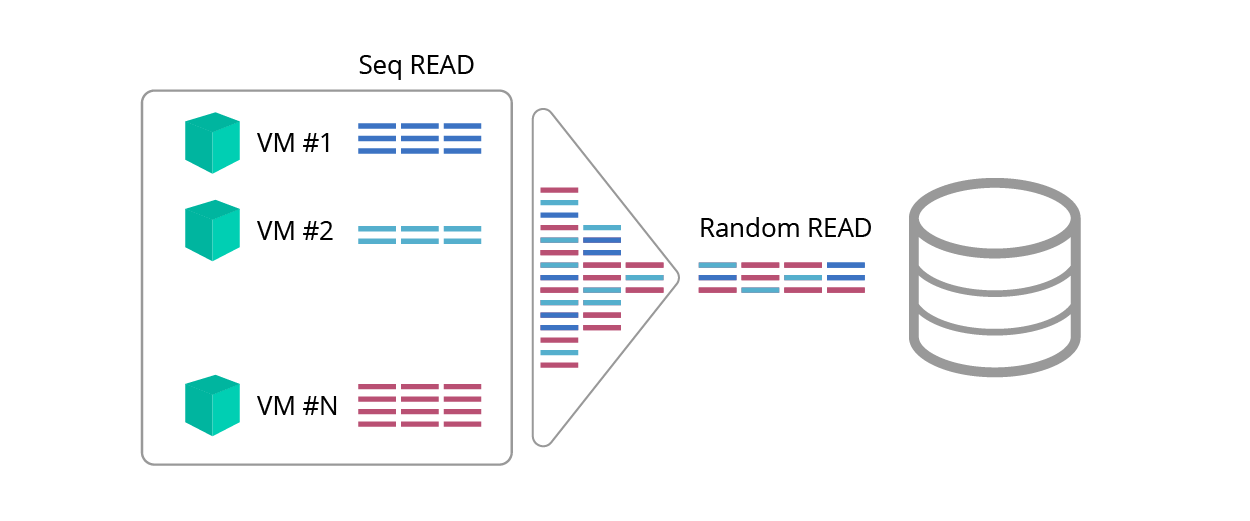

Consistent reading is predictable, but the reader may object: “But what about the blender effect <pic. 1>, which makes sequential requests random as a result of traffic mixing? ”

Fig. 1. Blender effect

Is it possible that Knowles become Dunno as a result of such confusion?

To the help of Znayka come a read-ahead algorithm and a detector that can identify different types of requests.

Read ahead

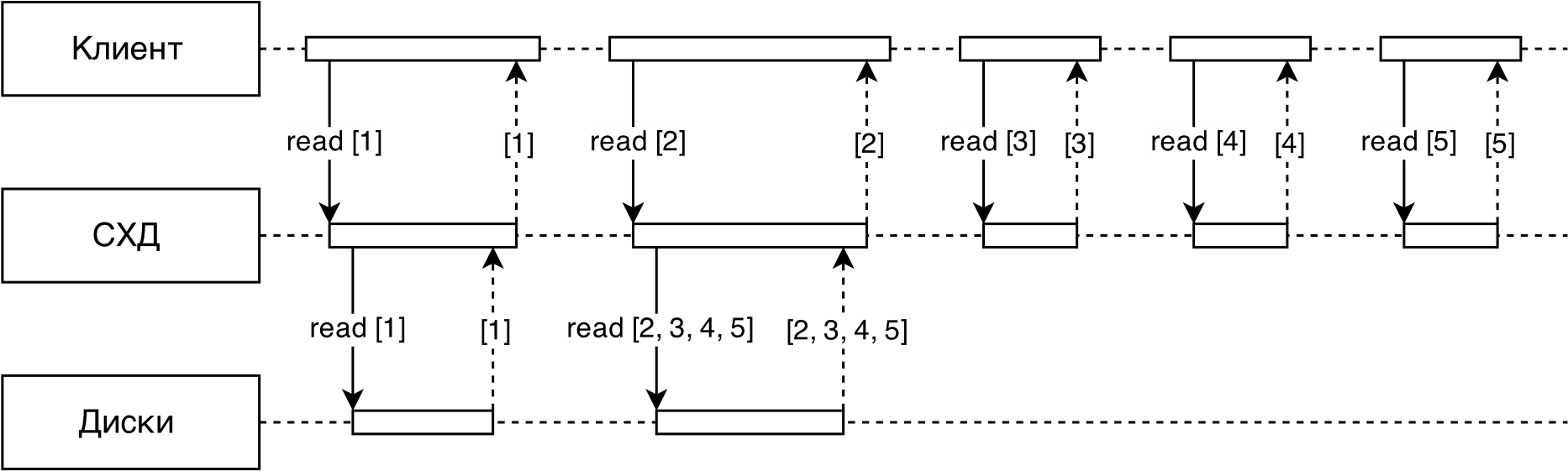

One of the main optimization methods, designed to reduce access time and increase throughput, is the use of read ahead technology. The technology allows, based on already requested data, to predict which data will be requested next, and transfer it from slower storage media (for example, from hard drives) to faster (for example, RAM and solid state drives) before this data is accessed (fig. 2).

In most cases, read-ahead is used for sequential operations.

Fig. 2. Read

-ahead reading. The work of the forward reading algorithm is usually divided into two stages:

- detection of sequential read requests in the stream of all requests;

- making a decision about the need to read data ahead and reading volumes.

Detector Implementation in RAIDIX

RAIDIX's forward-reading algorithm is based on the concept of ranges corresponding to the connected intervals of the address space.

Ranges are indicated in pairs (

The detector algorithm works as follows:

1. For each incoming read request, the nearest ranges are searched within the strideRange radius .

1.1. If none were found, a new random range is created with the address and length corresponding to the characteristics of the request. In this case, one of the existing ranges can be replaced by LRU.

1.2. If there is one range, the query is added to it with an extension of the interval. A random range can be converted to a serial one.

1.3. If there are two ranges (left and right), they are combined into one. The range resulting from this operation can also be converted to serial.

2. In the event that the request is in a sequential range, read-ahead can be performed for this range.

The read ahead option may vary depending on the flow rate and block size.

Figure 3 schematically shows the adaptive read-ahead algorithm implemented in RAIDIX.

Fig. 3. Read-ahead Scheme

All requests to the storage system from the client first go to the detector; its task is to isolate sequential streams (to distinguish sequential requests from random ones).

Further, for each sequential stream, its speed is determined

Each thread maps to a read-ahead option.

Thus, using the read-ahead algorithm, we can cope with the “I / O blender” effect and for sequential requests we guarantee throughput and latency comparable to the parameters of RAM.

Thus, Znayka defeats Dunno!

Random read performance

How can you increase the performance of random reading?

For these purposes, the developers of Vintik and Shpuntik offer to use faster media, namely SSD and a hybrid solution (tearing or SSD cache).

You can also use the random query accelerator - the C-Miner read-ahead algorithm.

The main task of all these methods is to put Dunno on a “fast” car :-) The problem is that you need to be able to drive a car, and Dunno is too unpredictable.

C-miner

One of the most interesting algorithms used for read-ahead in random queries is C-Miner, based on the search for correlations between the addresses of sequentially requested data blocks.

This algorithm detects semantic relationships between requests, such as requesting file system metadata before reading their corresponding files or finding a record in the DBMS index.

The work of C-Miner consists of the following steps:

- In the I / O request address sequence, repeating short subsequences are found, limited to a window of some size.

- Suffixes are extracted from the obtained subsequences, which are then combined in accordance with the frequency of occurrence.

- Based on the extracted suffixes and suffix chains, rules of the form {a → b, a → c, b → c, ab → c} are generated that describe which data blocks are preceded by requests for addresses from the correlating area.

- The resulting rules are ranked according to their reliability.

The C-Miner algorithm is well suited for storage systems in which data is rarely updated but often requested in small batches. Such a use case allows you to create a set of rules that will not expire for a long time, and also will not slow down the execution of the first queries (which appeared before the rules were created).

In a classic implementation, many rules with low reliability often arise. In this regard, read-ahead algorithms do pretty poorly with random queries. It is much more efficient to use a hybrid solution, in which the most popular queries fall on more productive drives, for example, SSD or NVME disks.

SSD cache or SSD peering?

The question arises, which technology is better to choose: SSD cache or SSD peering? A detailed analysis of the workload will help answer this question.

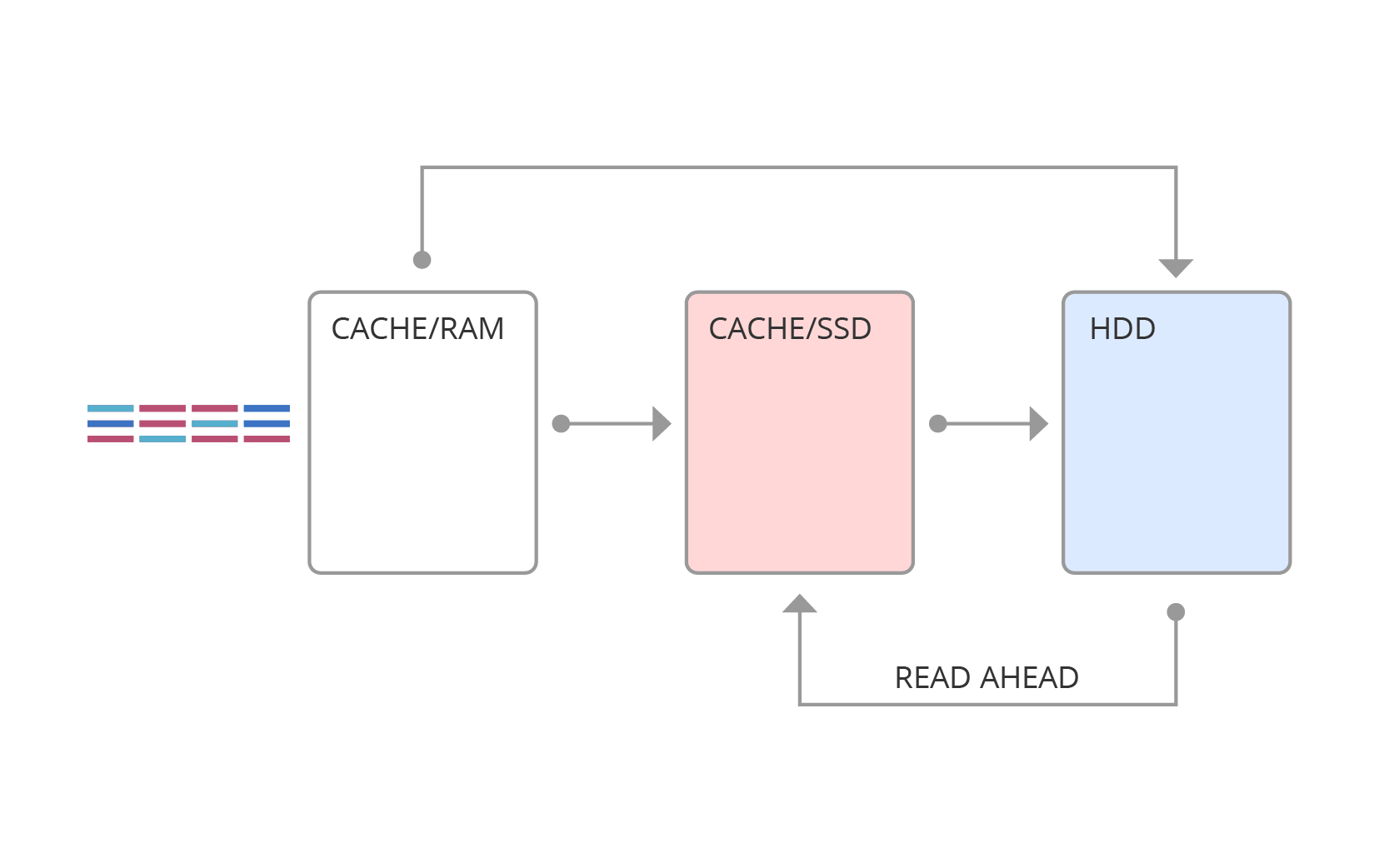

The SSD cache is schematically shown in Figure 4. Here, the requests first go to RAM, and then, depending on the type of request, they can be forced into the SSD cache or into main memory.

Fig. 4. SSD cache

SSD peering has a different structure (Fig. 5). When tiring, statistics of hot regions are kept, and at fixed times, hot data is transferred to a faster medium.

Fig. 5. SSD peering

The main difference between SSD cache and SSD peering is that the data in the tearing is not duplicated, unlike the SSD cache, in which hot data is stored both in the cache and on the disk.

The table below shows some selection criteria for a particular solution.

| Tearing | Cache | |

|---|---|---|

| Research method | Prediction of Future Values | Identifying localities in data |

| Workload | Predictable. Weakly changing | Dynamic, unpredictable. Instant reaction required |

| Data | Not duplicated (disk) | Duplicated (buffer) |

| Data migration | Offline algorithm, relocation window. There is a time parameter for moving data | Online algorithm, data is pushed out and cached on the fly. |

| Research Methods | Regression models, prediction models, long-term memory | Short-term memory, displacement algorithms |

| Interaction | HDD SSD | RAM-SSD, interacting with SSDs through read-ahead algorithms |

| Block | Large (e.g. 256 MB) | Small (e.g. 64 KB) |

| Algorithm | Function depending on transfer time and statistical characteristics of memory addresses | Cache Wipe and Fill Algorithms |

| Read / write | Random reading | Any requests, including writing, with the exception of sequential reading (in most cases) |

| Motto | The harder the better | The simpler the better |

| Manual transfer of desired data | Available | Not possible - contrary to cache logic |

At the heart of any hybrid solution, one way or another, is the prediction of the future load. In tearing, we are trying to predict the future from the past, in the SSD cache we believe that the probability of using recent and frequency queries is higher than long-used and low-frequency queries. In any case, the basis of the algorithms is the study of the "past" load. If the nature of the load changes, for example, a new application starts to work, then it takes time for the algorithms to adapt to the changes.

Dunno is not to blame (he has such a character - random) that the hybrid solution is poorly managed in an unknown new locality!

But even with the right “prediction”, the performance of the hybrid solution will be low (significantly lower than the maximum performance that an SSD can give).

Why? The answer is below.

How many IOPS to expect from an SSD cache?

Suppose we have a 2TB SSD cache, and the cached volume is 10TB in size. We know that some process randomly reads the entire volume with a uniform distribution. We also know that from the SSD cache we can read at a speed of 200K IOPS, and from an uncached area with a speed of 3K IOPS. Suppose that the cache is already full, and it contains 2TB of 10 readable. How many IOPS will we receive? The obvious answer comes to mind: 200K * 0.2 + 3K * 0.8 = 42.4K. But is it really that simple?

Let's try to figure it out by applying a little math. Our calculations deviate somewhat from real practice, but are perfectly acceptable for evaluation purposes.

DANO:

Let x% of the read data (or even requests) lie (are processed) in the SSD cache.

We believe that the SSD cache processes requests at a speed of u IOPS. And requests going to the HDD are processed at v IOPS.

SOLUTION:

To begin with, consider the case when iodepth (depth of the queue of requests) = 1.

We take the size of the entire read space as 1. Then the proportion of data (requests) located (processed) in the cache will be x / 100.

Let it be processed in 1 second

Take for

Since we are now considering only one second, then

We have the following equality (1):

We also have the following (2):

We substitute in (1) obtained from (2) I:

We know

Got the times

Simplify the equality:

Excellent! Now we know the number of IOPS with iodepth = 1.

What will happen when iodepth> 1? These calculations will become incorrect, or rather, not quite true. You can try to consider several parallel flows, for each of which iodepth = 1, or think of a different way, but with a sufficient test duration, these inaccuracies will be smoothed out, and the picture will be the same as with iodepth = 1. The result will still reflect the real picture .

So, answering the question “how much will IOPS be?”, We apply the formula:

GENERALIZATION

But what if we do not have a uniform distribution, but some closer to life?

Take, for example, the Pareto distribution (80/20 rule - 80% of requests go to 20% of the “hottest” data).

In this case, the resulting formula also works, since we nowhere rely on the size of the space and the size of the SSD. It is only important for us to know how many% of requests (in this case, namely requests!) Are processed in the SSD.

If the size of the SSD cache is 20% of the total read space and contains these 20% of the hottest data, then 80% of the requests will go to the SSD. Then, according to the formula I (80, 200000, 3000) ≈ 14150 IOPS. Yes, most likely it is less than you thought.

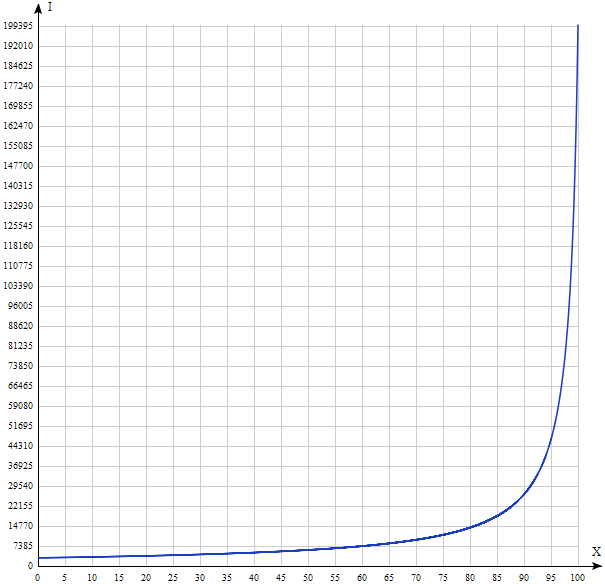

Let's plot I (x) for u = 200000, v = 3000.

The result is significantly different from the intuitive one. Thus, handing over the keys to a fast car to Dunno, we can not always speed up system performance. As you can see from the graph above, only an All-Flash solution (where all drives are solid-state) can really speed up random reading to the maximum “squeezed” out of an SSD drive. Blame it is not Dunno and, of course, not the developers of data storage systems, but simple mathematics.