Breaking up the complex: a road map of effective collaboration

Collaboration and collaboration within a network structure rarely leads to the achievement of ambitious stated goals. That's what you need to make them work.

Hi, Habr! I present to you the translation of the article Cutting Through the Complexity: A Roadmap for Effective Collaboration .

Cooperation is attractive in its concept, but difficult in practice. Although there are large online resources to support collaborative efforts, such as the Community Tool Box, the Intersector Project, and the NewNetworkLeader.org, the fact remains: we, the people, are simply not doing very well the “we-work”. And yet, the majority has changed their minds, and recognizes that in order to solve the complex social and environmental problems that we face, we must learn to interact among organizations, sectors, networks and interactions, taking into account our differences in attitudes and approaches. Effective collaboration should be a reality, not just a desire.

Most of us are familiar with the problems of cooperation: personal conflicts interfere; participants avoid difficult conversations; people are too formal and polite; we do not take the time to consciously build a relationship of trust; we do not understand leadership in the context of cooperation; we cannot allocate resources to core coordination functions so that collaboration can truly flourish.

Based on many papers, we have developed a roadmap that overcomes all these difficulties. We have tested and improved this structure for many years in different areas, and we tend to apply it in the spirit of the statistics of George Box, who said: “All models are wrong. Some models are useful. ” We found this roadmap useful and we hope that it will also be useful for others.

Although the reason for cooperation and who participates in cooperation may vary greatly in each particular case, the process of cooperation itself is remarkably amenable to a common description. Starting and maintaining effective cooperation and joint efforts requires that we pay close attention to five points:

These points help us navigate the personal, political, cultural and organizational dynamics inherent in joint efforts. These items can never be fully implemented, and they are not strictly linear. They inevitably get stuck on each other and require revision as part of the joint efforts.

Although it is not possible to know exactly what will happen until people are actually in the same room together, the goal of the roadmap is to map out the “conscious” aspect of the collaborative process — an aspect that you can largely plan and achieve a solution. Below we describe why each of these points is important, what tactics can be used to solve each problem and how to implement it in practice.

Although the goal of cooperation — its reason for being — may change over time, the initial choice of a priority goal is important in order to bring people together. As Simon Sinek said in his famous speech at the TED conference, “start by asking why.”

The goal should be ambitious enough to inspire, clear enough to identify the right participants and specific enough to focus the collaboration process. Collaboration may be limited to a problem, geography, population, result, or a combination of the above. For example, the priority goal of the RE-AMP network is to “reduce pollution from global warming by 80 percent by 2050 in eight states in the Midwest.” The ultimate goal of the California Summer Matters Network is “to increase and improve summer learning opportunities for all children and youth across the state.”

Refining the goal also entails a meaningful understanding of the problem. Albert Einstein said well that if he had an hour to save the world, he would have spent the first 55 minutes understanding the problem, and the remaining 5 minutes solving it. This process is what the design community calls "sensemaking - creating meaning."

Creating meaning includes identifying perspectives, developing a common understanding of the actors and organizations involved, and understanding external trends and forces. It also implies an understanding of the importance of the local context, the influence of the history of a place or system, the definition of political and energy dynamics, and the making of reasonable assumptions.

Through such a study of the system, participants become aware of their differences, as well as learn about the perspectives that unite them, and about their common values. This becomes the basis on which participants can take action and ultimately solve the most complex problems for which they have no agreement.

“The most scarce resource is not oil, metals, clean air, capital, labor, or technology,” said once the system theorist Donella Meadows. "We are ready to listen to each other and learn from each other and seek the truth, and not try to be right."

The Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network (SCMSN) is an interregional, intersectoral network structure that includes 19 organizations that work together to improve land management in the 500,000-acre region of California between San Francisco and Monterey Bay. Participants include federal agencies, state and county departments, land trusts, non-profit organizations, the largest timber industry company in the region, research institutes, special districts and the largest tribal group of indigenous peoples.

The network was originally formed at the end of 2014, when a number of large state and private landowners and managers realized that, although their organizations are ready for everything to take care of the region’s natural resources, they do not work together to the extent necessary for the prosperity of nature and man. area. They realized that they needed a joint approach, but they also realized that social fragmentation (the region has a history of tension and distrust) will limit progress.

Before the first meeting in the framework of cooperation, we had personal conversations with more than 20 potential participants. Since these conversations were confidential, participants honestly shared their thoughts, concerns and hopes for cooperation. As expected, we heard concerns about the "pitfalls" and learned that the participants had very different priorities in their daily work. However, despite significant disagreements, there was also a significant number of points of contact. Participants generally agreed that effective management requires a “mosaic approach” that takes into account the diversity of land use. They recognized the value of sustainable logging and were aware of the threats from real estate development and climate change. It is important to note that everyone agreed that the region,

As part of the initial cooperation invitation, we anonymously reflected what we learned and communicated to all groups, recognizing the differences and emphasizing areas of agreement. As a result, participants were able to start developing applications for the development of a priority goal a few hours before their first meeting, thereby clarifying the purpose of working together and outlining the direction of working together.

During the first two meetings, participants also completed a historical analysis of the region, looked at external trends and forces, looked at possible scenarios, and defined common values. This assessment process has helped this network structure to develop its priority objective in a memorandum of understanding, which all 19 members ratified at the end of their third meeting.

Attracting the "right" people means uniting everyone who is needed to accomplish the task. Although there is no one right answer to the question of who to attract, we agree with Marvin Weissbord and Sandra Janoff, creators of the planning process for the “Future Search”, who write: “The more far-reaching your goal, the higher your need for widespread involvement of the most different players. " According to Weissboard and Yanoff, this implies attracting people with:

We will add two more groups of “right” people. First, the “right” people include those who have the ability to listen deeply and evaluate different perspectives. As the author Margaret Wheatley wrote: "The real listening always brings people together."

Secondly, the “right” people are those who remain involved in cooperation. In the course of any joint efforts, as a rule, some people will leave the group, while others will continue to participate in the process of developing cooperation. With effective cooperation, the “right” people appear, take part and leave the group, and this is normal and proper.

Attracting the right people does not necessarily mean making a call to anyone who might be interested in this issue. A broad invitation to cooperate is often motivated by the fact that many people are scared to identify the elect, when determining the wide range of participants who should be involved. Researchers at the University of Colorado's Denver Network Science Center found that collaboration, which begins and develops through “thoughtful inclusion,” usually shows longer-term sustainability and effectiveness. Instead of interacting with all possible participants, thoughtful inclusion begins with the recruitment of a core group of dedicated individuals and organizations, one after the other, clarifying the original goal and approach to solving the problem.

In our opinion, trust is the single most important component of effective cooperation. Trusting relationships should not be “pleasant” - they should be trusting. The network of relationships that develops between the participants is an invisible structure that makes cooperation work. Trust, however, has become something of a buzzword. Everyone says that this is important, but the inability to develop trusting relationships is what makes cooperation break down.

Google recently spent millions of dollars and thousands of hours trying to figure out why some teams stumble while others take off - an initiative called Project Aristotle. They looked at half a century of academic research and studied hundreds of teams, trying to find evidence for the general assumption that the composition of the team matters. “We looked at 180 teams from all companies,” said Abeer Duby, project manager, in the New York Times Magazine article about the initiative. “We had a lot of data, but nothing indicated that the combination of specific personality types or skills, or the background had any meaning. The “who” part of the equation doesn't seem to matter. ”

In the end, Google found that high-performance teams have a high level of “psychological security”, which is expressed in equal opportunity to speak in team discussions, as well as a high degree of social sensitivity or in other words the ability of group members to read each other’s social signals. Psychological security, as determined by Amy Edmondson, a professor at Harvard Business School, is “the overall conviction of team members that the team is safe for interpersonal risk”, and “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish anyone for saying ... a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people feel comfortable being themselves. "

In other words, people work together most effectively when relationships are strong and authentic. When they listen to others and feel free to express their opinions. When they value diversity of thought and experience and can use the unique gifts that each person brings. When there is a high degree of mutual respect and, in one word, trust.

Trust is not the same as “liking” or “consent.” To work together, people do not need to like each other. And they should not agree with each other on each issue. When we talk about trust, we mean trust in action - what we call “heart-to-heart talk”. A type of trusting relationship that allows you to overcome tensions in difficult conversations, resolve an emerging conflict, and find common ground and make cooperation a reality, not just a desire. We also found that confidence can be built up much faster than many people think, if we strive for this purposefully.

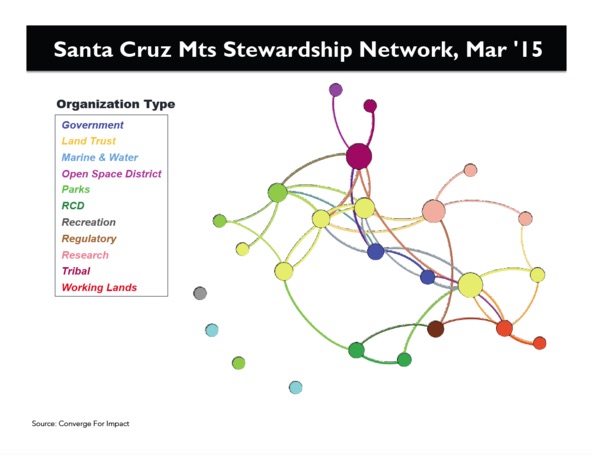

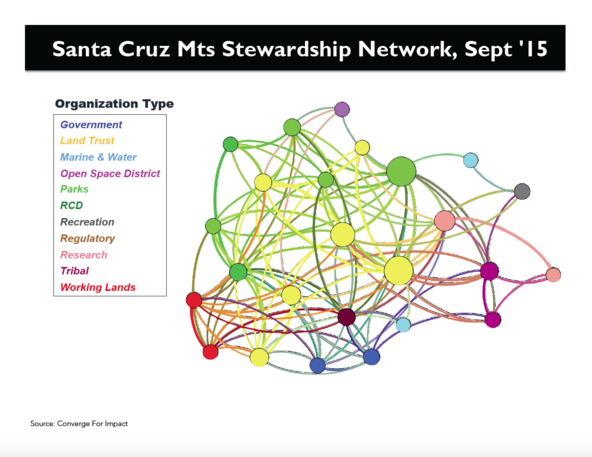

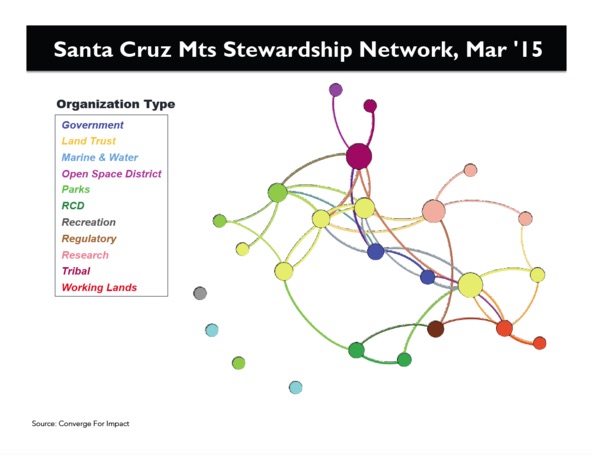

For the Santa Cruz Mountains support network, we conducted a social network analysis immediately before the first meeting in March 2015 and every six months thereafter monitored and supported the growth of this relationship. This data helped us to strategically “bind” communications in the network in order to maximize the opportunities of collaboration.

Below are the network cards illustrating this work. Each circle, or “node,” is a member of the network. The colors indicate the type of organization they represent, and each of the lines connecting the nodes means a personal or professional connection between the participating organizations. Initially, the network was fragmented, as seen on the first map, especially in terms of connections between different types of organizations.

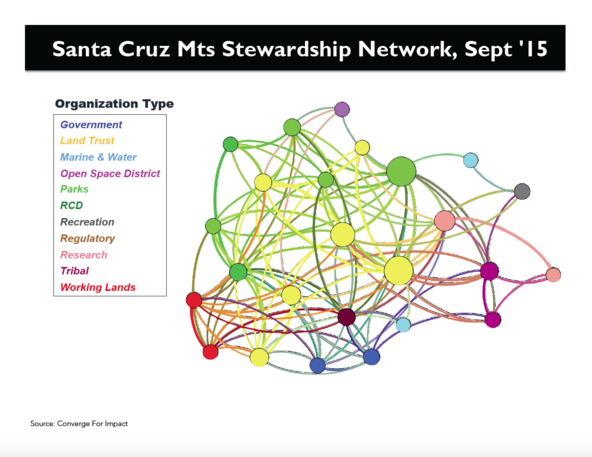

On the second map, you can see that after two meetings, during which we deliberately devoted time to establishing a basic level of trust between previously not involved participants, the system became much more interconnected. Even if network members never met after September 2015, relationships remained much more stable than before the network was created. New and deeper relationships, stronger information flows and greater recognition of opportunities for collaboration between organizations have emerged.

When people identify a common goal and create trust, they are much more inclined to look for and track opportunities to support each other’s work. This requires that participants share information about the work they are already doing, in the framework of cooperation. As a result, participants find opportunities to work together, quickly achieve results and avoid duplication of effort.

Working together, even to a small extent, allows participants to strengthen their relationships with each other, creating a positive cycle of trust and action. An analysis of the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, a community of 60 communities across the United States working to create higher resilience to forest fires, shows a strong statistical correlation between the depth of the relationship between the two participants and their perception of the possibilities of cooperation between them. In other words, as relations develop, the participants find more opportunities for cooperation, which, in turn, strengthens their relations.

However, the altruistic commitment of the participants is not enough to maintain cooperation. On the contrary, cooperation should also serve the personal and organizational goals of individual participants. Otherwise, they will not be able to justify the time and effort required for full participation. The coincidence between personal goals and common goals of cooperation is what we call the intersection of personal interests and common interests, and finding the right balance between them is important.

To do this, participants at the initial stage of team building should have the opportunity to publicly announce their capabilities - what they can give as part of cooperation to support other participants and personal goals - the conditions under which they leave the project are necessary to make participation worth it. The more specifically it is formulated, the better the participants will understand the conditions of interaction with each other. Examples of what participants can give include: links to sources of funding or influential individuals, access to a volunteer base or a fleet of vehicles, time and energy to participate in the work of other partners. Examples of what participants can get in return: the services of a professional writer, the potential or experience to support the project, the conference room for the meeting and other tangible results and opportunities.

Participants must also express legal restrictions on their contributions. Other participants, when faced with these restrictions, may perceive the absence of such restrictions as a failure to fulfill obligations or a failure of cooperation. Restrictions may include issues such as the time that participants may spend in the framework of cooperation, providing advice, and for management representatives there may be legal restrictions on their ability to participate in cooperation.

In order for real changes to take place in the system, joint efforts should be directed at eliminating the root causes of problems, and not just at alleviating the symptoms. To get rid of a toothache, it is necessary to cure a tooth, but we will never achieve long-term positive changes without paying attention to the root cause of the problem, for example, the need to teach young children to monitor their teeth and clean them regularly.

Finding root causes necessarily requires recognizing and resolving systemic and structural issues such as racism, sexism, and income inequality. As Unius Williams and Sarah Marker wrote in their article “Bringing an Objective Look to Collective Impact”: “Without close attention to sustainable inequality, our initiatives risk remaining inefficient and inappropriate improvements that cannot be sustained.” And, according to the authors, “Cooperation in the Interests of Equality and Justice”, “this requires that cooperation include the principles of equality and fairness and take into account their influence in the distribution of power and resources, setting the agenda for social change and current commitments in terms of Equality and Justice. "

One of the ways to solve the root problems is to identify and influence “points of influence” that contribute to the achievement of the priority goal of cooperation. Points of influence are places in the system where, as Meadows said, "a small change in one aspect can make a big change in everything." Within the framework of collaboration, points of influence can also represent opportunities for participants to have a greater impact by working together than they could have by working alone.

100Kin10, a community of more than 200 partners that supports STEM teachers, by 2021 they want to train 100,000 of the best STEM teachers, have attracted hundreds of teachers to identify 100 problems that stand in the path of STEM quality education for everyone and evaluate the interrelationships between these problems. Through this process, 100Kin10 identified six main points of influence on the achievement of its goal: 1) raise state standards, 2) improve the quality of the curriculum, 3) expand financial support for major STEM colleges, 4) develop accountability systems that promote teacher creativity, 5) increase the time available for professional development, and 6) increase the time available for teacher cooperation.

In addition to the comprehensive system mapping method that used 100Kin10, collaboration can determine points of influence during training sessions on managing network structures or using a design-oriented approach that allows you to quickly move from idea to prototyping. Collaboration should then provide participants with an opportunity for action, for example, in a project-oriented project team. Participants are more willing to participate when they feel that their efforts can have an effect, and their priorities coincide with the work of the team.

In addition to the roadmap, effective collaboration also requires specific management, structure, coordination, and funding to achieve its goals.

Governance: Because collaborations and network structures are collaborative actions, formal management procedures can help participants make timely decisions, invite new members, plan and successfully conduct meetings, and integrate a set of interactive collaboration tools. The goal of good governance is “not to tell members what to do, but so that they can do what they want to do,” writes Madeleine Taylor, Peter Plastrick and John Cleveland in their article “Joining the Changing World.”

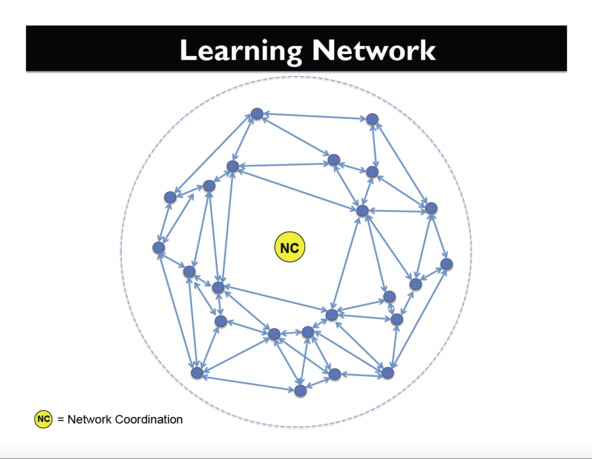

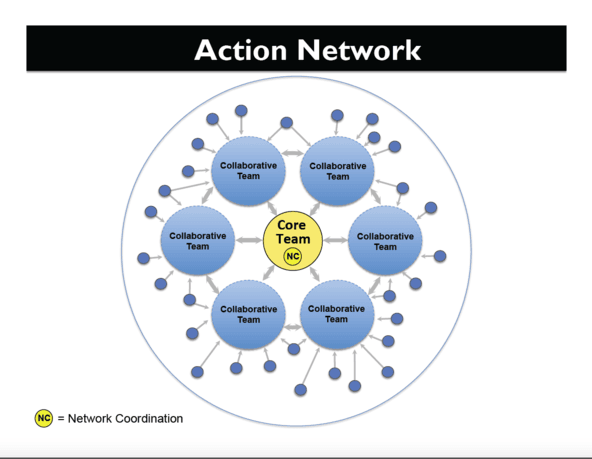

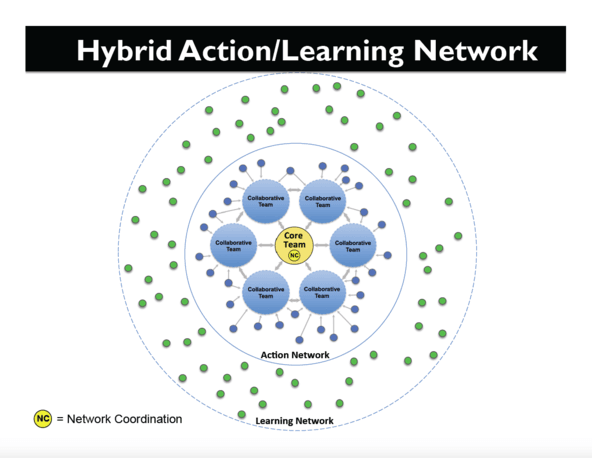

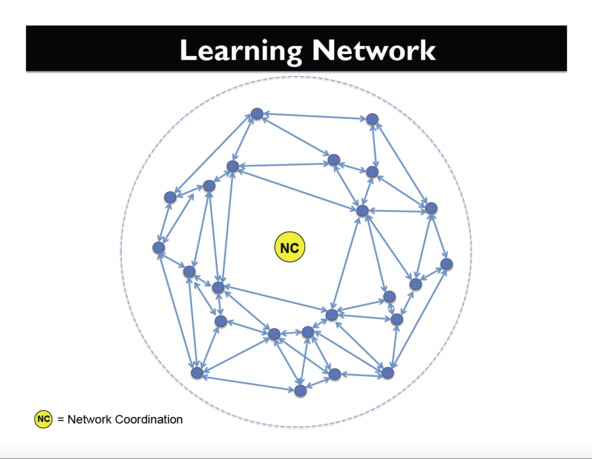

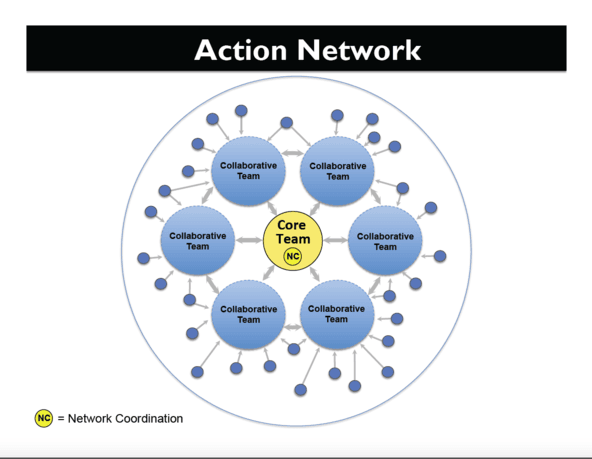

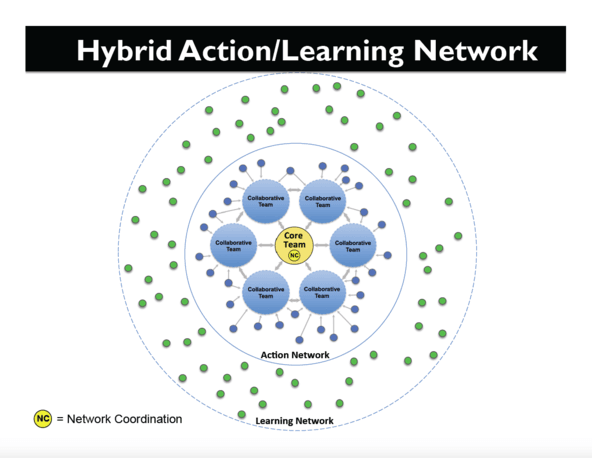

Structures.From our point of view, the network is a structure that provides interaction. The correct network structure allows the collaboration to efficiently direct the creative impulses of its members. But too many structural factors stifle individual initiative, and also lead to an increase in the number of rules and procedures. According to Francis Butterfoss, the author of coalitions and public health partnerships, “you need to adopt the simplest structure that will achieve the goals of collaboration.”

The following are examples of basic network structures within which cooperation can take place:

Educational network structures - Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network

Network structures aimed at performing functions - RE-AMP Network

Mixed network structures: training and performance of functions - California Summer Matters Network

Networks consisting of network structures - Network for Landscape Conservation

Coordination. Cooperation can not achieve ambitious goals only through self-organization. Some form of coordination is needed to mobilize people and resources to solve complex problems. Those who fulfill this role are called system leaders, system entrepreneurs, network leaders, network entrepreneurs, strategic organizers and maintainers. Regardless of what they are called, their main role is coordination.

The role of the coordinator or group of coordinators is to constantly feel and respond to the emerging needs of cooperation as it develops. They work to help participants clarify the goal and the values that unite them, determine who else needs to be engaged, cultivate trust, find opportunities for mutual benefit, and intensify joint actions to achieve common goals. Coordinators are not looking for attention. Instead, they are usually motivated in their work by the goal of cooperation and their ability to help others achieve their potential.

We found it useful to consider coordination as a set of responsibilities, which can be divided conditionally into three parts:

Lawn in front of the house:external communications, public relations and outreach, and resources.

In the house: building relationships, process design, organizing meetings, managing conflicts, finding and attracting new members.

Garden in the yard: logistic preparation for meetings, project tracking, performance evaluation, financial planning and technical support

Financing:Cooperation requires the provision of resources, in particular finances. As the authors of the recent Harvard Business Review article “Audacious Philanthropy / Bold Philontropy” write: “Collaboration of any type can be difficult and costly, so few philanthropists support or participate in it, although most of them are disappointed by the inefficiency of efforts with meaningless results in the end.” However, foundations and philanthropists play an important, unique role in supporting collaboration and networking.

The main task of sponsors is to support cooperation without limiting or controlling this cooperation. Financiers should be ready to give participants the opportunity to determine the purpose and direction of cooperation, or they risk strangling the very energy that feeds cooperation.

Fund "S. D. Bechtel Jr. ”discovered that he can effectively support cooperation and network structures in order to implement new solutions adhering to the following principles:

Social philosopher Tom Utley wrote what is a good summary for what is happening on the planet right now: "Everything is getting better and better, worse and worse, faster and faster, at the same time." If he is right, and we think that this is the case, then we urgently need to consider two questions: how can we strengthen everything that gets better and better? And how can we minimize the damage from things that are getting worse and worse?

We believe that the answer to both questions is to improve effective cooperation, that is, meaningful attempts to work together for the benefit of a common goal - between fragmented organizations, sectors and networks. From our point of view, it would not be an exaggeration to say that our ability to work effectively together with all our differences is the last great hope for humanity.

David Ehrlichman, David Sawyer and Matthew Spence are partners of Converge, a group of strategists and designers committed to social and environmental influence through collaboration and network structures. In their work with Converge, they helped to establish intersectoral collaboration and networking on issues as diverse as economic mobility, environmental protection, human rights, and health care reform.

Ehrlichman was previously the network coordinator for the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network and the New Leadership Network of the James Irving Foundation, and also a consultant for the Monitor Institute. He co-authored with Sawyer and Jane Wei-Skirner of previous articles in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, including “The Most Influential Leaders You Never Heard” and “Confidence Tactics”.

Sawyer is also the president of Context, a consulting firm with practical directions in strategy, leadership and culture. Previously, he led the leadership and service programs at Berea College, receiving the “Servant Leader Award” from the National Council on Youth Leadership, helped launch the American Americorps program and became the first executive director of Social Venture Partners Portland.

Spence is also president of Spence & Company, where he conducts training for professionals in a wide variety of industries, how to organize complex information for more effective communication. He previously served as research director for five years at Amana-Key, one of the leading executive firms in Brazil, and recently led a collaborative effort by Fortune 100 technical companies and their suppliers to improve sustainable supply chain management practices.

Hi, Habr! I present to you the translation of the article Cutting Through the Complexity: A Roadmap for Effective Collaboration .

Cooperation is attractive in its concept, but difficult in practice. Although there are large online resources to support collaborative efforts, such as the Community Tool Box, the Intersector Project, and the NewNetworkLeader.org, the fact remains: we, the people, are simply not doing very well the “we-work”. And yet, the majority has changed their minds, and recognizes that in order to solve the complex social and environmental problems that we face, we must learn to interact among organizations, sectors, networks and interactions, taking into account our differences in attitudes and approaches. Effective collaboration should be a reality, not just a desire.

Most of us are familiar with the problems of cooperation: personal conflicts interfere; participants avoid difficult conversations; people are too formal and polite; we do not take the time to consciously build a relationship of trust; we do not understand leadership in the context of cooperation; we cannot allocate resources to core coordination functions so that collaboration can truly flourish.

Based on many papers, we have developed a roadmap that overcomes all these difficulties. We have tested and improved this structure for many years in different areas, and we tend to apply it in the spirit of the statistics of George Box, who said: “All models are wrong. Some models are useful. ” We found this roadmap useful and we hope that it will also be useful for others.

Five points for an effective collaboration roadmap

Although the reason for cooperation and who participates in cooperation may vary greatly in each particular case, the process of cooperation itself is remarkably amenable to a common description. Starting and maintaining effective cooperation and joint efforts requires that we pay close attention to five points:

- clarification of the goal;

- attracting the right people;

- confidence building;

- coordination of current activities;

- cooperation for the purpose of systemic exposure.

These points help us navigate the personal, political, cultural and organizational dynamics inherent in joint efforts. These items can never be fully implemented, and they are not strictly linear. They inevitably get stuck on each other and require revision as part of the joint efforts.

Although it is not possible to know exactly what will happen until people are actually in the same room together, the goal of the roadmap is to map out the “conscious” aspect of the collaborative process — an aspect that you can largely plan and achieve a solution. Below we describe why each of these points is important, what tactics can be used to solve each problem and how to implement it in practice.

1. Clarification of the goal

Although the goal of cooperation — its reason for being — may change over time, the initial choice of a priority goal is important in order to bring people together. As Simon Sinek said in his famous speech at the TED conference, “start by asking why.”

The goal should be ambitious enough to inspire, clear enough to identify the right participants and specific enough to focus the collaboration process. Collaboration may be limited to a problem, geography, population, result, or a combination of the above. For example, the priority goal of the RE-AMP network is to “reduce pollution from global warming by 80 percent by 2050 in eight states in the Midwest.” The ultimate goal of the California Summer Matters Network is “to increase and improve summer learning opportunities for all children and youth across the state.”

Refining the goal also entails a meaningful understanding of the problem. Albert Einstein said well that if he had an hour to save the world, he would have spent the first 55 minutes understanding the problem, and the remaining 5 minutes solving it. This process is what the design community calls "sensemaking - creating meaning."

Creating meaning includes identifying perspectives, developing a common understanding of the actors and organizations involved, and understanding external trends and forces. It also implies an understanding of the importance of the local context, the influence of the history of a place or system, the definition of political and energy dynamics, and the making of reasonable assumptions.

Through such a study of the system, participants become aware of their differences, as well as learn about the perspectives that unite them, and about their common values. This becomes the basis on which participants can take action and ultimately solve the most complex problems for which they have no agreement.

“The most scarce resource is not oil, metals, clean air, capital, labor, or technology,” said once the system theorist Donella Meadows. "We are ready to listen to each other and learn from each other and seek the truth, and not try to be right."

The Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network (SCMSN) is an interregional, intersectoral network structure that includes 19 organizations that work together to improve land management in the 500,000-acre region of California between San Francisco and Monterey Bay. Participants include federal agencies, state and county departments, land trusts, non-profit organizations, the largest timber industry company in the region, research institutes, special districts and the largest tribal group of indigenous peoples.

The network was originally formed at the end of 2014, when a number of large state and private landowners and managers realized that, although their organizations are ready for everything to take care of the region’s natural resources, they do not work together to the extent necessary for the prosperity of nature and man. area. They realized that they needed a joint approach, but they also realized that social fragmentation (the region has a history of tension and distrust) will limit progress.

Before the first meeting in the framework of cooperation, we had personal conversations with more than 20 potential participants. Since these conversations were confidential, participants honestly shared their thoughts, concerns and hopes for cooperation. As expected, we heard concerns about the "pitfalls" and learned that the participants had very different priorities in their daily work. However, despite significant disagreements, there was also a significant number of points of contact. Participants generally agreed that effective management requires a “mosaic approach” that takes into account the diversity of land use. They recognized the value of sustainable logging and were aware of the threats from real estate development and climate change. It is important to note that everyone agreed that the region,

As part of the initial cooperation invitation, we anonymously reflected what we learned and communicated to all groups, recognizing the differences and emphasizing areas of agreement. As a result, participants were able to start developing applications for the development of a priority goal a few hours before their first meeting, thereby clarifying the purpose of working together and outlining the direction of working together.

During the first two meetings, participants also completed a historical analysis of the region, looked at external trends and forces, looked at possible scenarios, and defined common values. This assessment process has helped this network structure to develop its priority objective in a memorandum of understanding, which all 19 members ratified at the end of their third meeting.

2. Attracting the right people

Attracting the "right" people means uniting everyone who is needed to accomplish the task. Although there is no one right answer to the question of who to attract, we agree with Marvin Weissbord and Sandra Janoff, creators of the planning process for the “Future Search”, who write: “The more far-reaching your goal, the higher your need for widespread involvement of the most different players. " According to Weissboard and Yanoff, this implies attracting people with:

- the authority to act and willing to take responsibility for decision making in an organization or community;

- resources such as contacts, time or money;

- expertise in the issues at hand;

- information on a topic that no one else has;

- shares in the final results and those who will use the results of cooperation.

We will add two more groups of “right” people. First, the “right” people include those who have the ability to listen deeply and evaluate different perspectives. As the author Margaret Wheatley wrote: "The real listening always brings people together."

Secondly, the “right” people are those who remain involved in cooperation. In the course of any joint efforts, as a rule, some people will leave the group, while others will continue to participate in the process of developing cooperation. With effective cooperation, the “right” people appear, take part and leave the group, and this is normal and proper.

Attracting the right people does not necessarily mean making a call to anyone who might be interested in this issue. A broad invitation to cooperate is often motivated by the fact that many people are scared to identify the elect, when determining the wide range of participants who should be involved. Researchers at the University of Colorado's Denver Network Science Center found that collaboration, which begins and develops through “thoughtful inclusion,” usually shows longer-term sustainability and effectiveness. Instead of interacting with all possible participants, thoughtful inclusion begins with the recruitment of a core group of dedicated individuals and organizations, one after the other, clarifying the original goal and approach to solving the problem.

3. Cultivating trust

In our opinion, trust is the single most important component of effective cooperation. Trusting relationships should not be “pleasant” - they should be trusting. The network of relationships that develops between the participants is an invisible structure that makes cooperation work. Trust, however, has become something of a buzzword. Everyone says that this is important, but the inability to develop trusting relationships is what makes cooperation break down.

Google recently spent millions of dollars and thousands of hours trying to figure out why some teams stumble while others take off - an initiative called Project Aristotle. They looked at half a century of academic research and studied hundreds of teams, trying to find evidence for the general assumption that the composition of the team matters. “We looked at 180 teams from all companies,” said Abeer Duby, project manager, in the New York Times Magazine article about the initiative. “We had a lot of data, but nothing indicated that the combination of specific personality types or skills, or the background had any meaning. The “who” part of the equation doesn't seem to matter. ”

In the end, Google found that high-performance teams have a high level of “psychological security”, which is expressed in equal opportunity to speak in team discussions, as well as a high degree of social sensitivity or in other words the ability of group members to read each other’s social signals. Psychological security, as determined by Amy Edmondson, a professor at Harvard Business School, is “the overall conviction of team members that the team is safe for interpersonal risk”, and “a sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish anyone for saying ... a team climate characterized by interpersonal trust and mutual respect in which people feel comfortable being themselves. "

In other words, people work together most effectively when relationships are strong and authentic. When they listen to others and feel free to express their opinions. When they value diversity of thought and experience and can use the unique gifts that each person brings. When there is a high degree of mutual respect and, in one word, trust.

Trust is not the same as “liking” or “consent.” To work together, people do not need to like each other. And they should not agree with each other on each issue. When we talk about trust, we mean trust in action - what we call “heart-to-heart talk”. A type of trusting relationship that allows you to overcome tensions in difficult conversations, resolve an emerging conflict, and find common ground and make cooperation a reality, not just a desire. We also found that confidence can be built up much faster than many people think, if we strive for this purposefully.

For the Santa Cruz Mountains support network, we conducted a social network analysis immediately before the first meeting in March 2015 and every six months thereafter monitored and supported the growth of this relationship. This data helped us to strategically “bind” communications in the network in order to maximize the opportunities of collaboration.

Below are the network cards illustrating this work. Each circle, or “node,” is a member of the network. The colors indicate the type of organization they represent, and each of the lines connecting the nodes means a personal or professional connection between the participating organizations. Initially, the network was fragmented, as seen on the first map, especially in terms of connections between different types of organizations.

On the second map, you can see that after two meetings, during which we deliberately devoted time to establishing a basic level of trust between previously not involved participants, the system became much more interconnected. Even if network members never met after September 2015, relationships remained much more stable than before the network was created. New and deeper relationships, stronger information flows and greater recognition of opportunities for collaboration between organizations have emerged.

4. Coordination of current activities

When people identify a common goal and create trust, they are much more inclined to look for and track opportunities to support each other’s work. This requires that participants share information about the work they are already doing, in the framework of cooperation. As a result, participants find opportunities to work together, quickly achieve results and avoid duplication of effort.

Working together, even to a small extent, allows participants to strengthen their relationships with each other, creating a positive cycle of trust and action. An analysis of the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, a community of 60 communities across the United States working to create higher resilience to forest fires, shows a strong statistical correlation between the depth of the relationship between the two participants and their perception of the possibilities of cooperation between them. In other words, as relations develop, the participants find more opportunities for cooperation, which, in turn, strengthens their relations.

However, the altruistic commitment of the participants is not enough to maintain cooperation. On the contrary, cooperation should also serve the personal and organizational goals of individual participants. Otherwise, they will not be able to justify the time and effort required for full participation. The coincidence between personal goals and common goals of cooperation is what we call the intersection of personal interests and common interests, and finding the right balance between them is important.

To do this, participants at the initial stage of team building should have the opportunity to publicly announce their capabilities - what they can give as part of cooperation to support other participants and personal goals - the conditions under which they leave the project are necessary to make participation worth it. The more specifically it is formulated, the better the participants will understand the conditions of interaction with each other. Examples of what participants can give include: links to sources of funding or influential individuals, access to a volunteer base or a fleet of vehicles, time and energy to participate in the work of other partners. Examples of what participants can get in return: the services of a professional writer, the potential or experience to support the project, the conference room for the meeting and other tangible results and opportunities.

Participants must also express legal restrictions on their contributions. Other participants, when faced with these restrictions, may perceive the absence of such restrictions as a failure to fulfill obligations or a failure of cooperation. Restrictions may include issues such as the time that participants may spend in the framework of cooperation, providing advice, and for management representatives there may be legal restrictions on their ability to participate in cooperation.

5. Collaboration for systemic impact.

In order for real changes to take place in the system, joint efforts should be directed at eliminating the root causes of problems, and not just at alleviating the symptoms. To get rid of a toothache, it is necessary to cure a tooth, but we will never achieve long-term positive changes without paying attention to the root cause of the problem, for example, the need to teach young children to monitor their teeth and clean them regularly.

Finding root causes necessarily requires recognizing and resolving systemic and structural issues such as racism, sexism, and income inequality. As Unius Williams and Sarah Marker wrote in their article “Bringing an Objective Look to Collective Impact”: “Without close attention to sustainable inequality, our initiatives risk remaining inefficient and inappropriate improvements that cannot be sustained.” And, according to the authors, “Cooperation in the Interests of Equality and Justice”, “this requires that cooperation include the principles of equality and fairness and take into account their influence in the distribution of power and resources, setting the agenda for social change and current commitments in terms of Equality and Justice. "

One of the ways to solve the root problems is to identify and influence “points of influence” that contribute to the achievement of the priority goal of cooperation. Points of influence are places in the system where, as Meadows said, "a small change in one aspect can make a big change in everything." Within the framework of collaboration, points of influence can also represent opportunities for participants to have a greater impact by working together than they could have by working alone.

100Kin10, a community of more than 200 partners that supports STEM teachers, by 2021 they want to train 100,000 of the best STEM teachers, have attracted hundreds of teachers to identify 100 problems that stand in the path of STEM quality education for everyone and evaluate the interrelationships between these problems. Through this process, 100Kin10 identified six main points of influence on the achievement of its goal: 1) raise state standards, 2) improve the quality of the curriculum, 3) expand financial support for major STEM colleges, 4) develop accountability systems that promote teacher creativity, 5) increase the time available for professional development, and 6) increase the time available for teacher cooperation.

In addition to the comprehensive system mapping method that used 100Kin10, collaboration can determine points of influence during training sessions on managing network structures or using a design-oriented approach that allows you to quickly move from idea to prototyping. Collaboration should then provide participants with an opportunity for action, for example, in a project-oriented project team. Participants are more willing to participate when they feel that their efforts can have an effect, and their priorities coincide with the work of the team.

Put it all together

In addition to the roadmap, effective collaboration also requires specific management, structure, coordination, and funding to achieve its goals.

Governance: Because collaborations and network structures are collaborative actions, formal management procedures can help participants make timely decisions, invite new members, plan and successfully conduct meetings, and integrate a set of interactive collaboration tools. The goal of good governance is “not to tell members what to do, but so that they can do what they want to do,” writes Madeleine Taylor, Peter Plastrick and John Cleveland in their article “Joining the Changing World.”

Structures.From our point of view, the network is a structure that provides interaction. The correct network structure allows the collaboration to efficiently direct the creative impulses of its members. But too many structural factors stifle individual initiative, and also lead to an increase in the number of rules and procedures. According to Francis Butterfoss, the author of coalitions and public health partnerships, “you need to adopt the simplest structure that will achieve the goals of collaboration.”

The following are examples of basic network structures within which cooperation can take place:

Educational network structures - Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network

Network structures aimed at performing functions - RE-AMP Network

Mixed network structures: training and performance of functions - California Summer Matters Network

Networks consisting of network structures - Network for Landscape Conservation

Coordination. Cooperation can not achieve ambitious goals only through self-organization. Some form of coordination is needed to mobilize people and resources to solve complex problems. Those who fulfill this role are called system leaders, system entrepreneurs, network leaders, network entrepreneurs, strategic organizers and maintainers. Regardless of what they are called, their main role is coordination.

The role of the coordinator or group of coordinators is to constantly feel and respond to the emerging needs of cooperation as it develops. They work to help participants clarify the goal and the values that unite them, determine who else needs to be engaged, cultivate trust, find opportunities for mutual benefit, and intensify joint actions to achieve common goals. Coordinators are not looking for attention. Instead, they are usually motivated in their work by the goal of cooperation and their ability to help others achieve their potential.

We found it useful to consider coordination as a set of responsibilities, which can be divided conditionally into three parts:

Lawn in front of the house:external communications, public relations and outreach, and resources.

In the house: building relationships, process design, organizing meetings, managing conflicts, finding and attracting new members.

Garden in the yard: logistic preparation for meetings, project tracking, performance evaluation, financial planning and technical support

Financing:Cooperation requires the provision of resources, in particular finances. As the authors of the recent Harvard Business Review article “Audacious Philanthropy / Bold Philontropy” write: “Collaboration of any type can be difficult and costly, so few philanthropists support or participate in it, although most of them are disappointed by the inefficiency of efforts with meaningless results in the end.” However, foundations and philanthropists play an important, unique role in supporting collaboration and networking.

The main task of sponsors is to support cooperation without limiting or controlling this cooperation. Financiers should be ready to give participants the opportunity to determine the purpose and direction of cooperation, or they risk strangling the very energy that feeds cooperation.

Fund "S. D. Bechtel Jr. ”discovered that he can effectively support cooperation and network structures in order to implement new solutions adhering to the following principles:

- ensuring flexibility of goals and results of cooperation;

- consideration of the development of trust as one of the results of joint work;

- “Creating opportunities” for other sponsors willing to support a joint project by investing in the operational potential of the network;

- support for specific joint activities, such as meetings, by facilitating organization and coordination issues;

- consider collaboration and participation in network structures as learning

- be ready to adapt their support to changing conditions, as cooperation changes over time.

Decisive moment

Social philosopher Tom Utley wrote what is a good summary for what is happening on the planet right now: "Everything is getting better and better, worse and worse, faster and faster, at the same time." If he is right, and we think that this is the case, then we urgently need to consider two questions: how can we strengthen everything that gets better and better? And how can we minimize the damage from things that are getting worse and worse?

We believe that the answer to both questions is to improve effective cooperation, that is, meaningful attempts to work together for the benefit of a common goal - between fragmented organizations, sectors and networks. From our point of view, it would not be an exaggeration to say that our ability to work effectively together with all our differences is the last great hope for humanity.

David Ehrlichman, David Sawyer and Matthew Spence are partners of Converge, a group of strategists and designers committed to social and environmental influence through collaboration and network structures. In their work with Converge, they helped to establish intersectoral collaboration and networking on issues as diverse as economic mobility, environmental protection, human rights, and health care reform.

Ehrlichman was previously the network coordinator for the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network and the New Leadership Network of the James Irving Foundation, and also a consultant for the Monitor Institute. He co-authored with Sawyer and Jane Wei-Skirner of previous articles in the Stanford Social Innovation Review, including “The Most Influential Leaders You Never Heard” and “Confidence Tactics”.

Sawyer is also the president of Context, a consulting firm with practical directions in strategy, leadership and culture. Previously, he led the leadership and service programs at Berea College, receiving the “Servant Leader Award” from the National Council on Youth Leadership, helped launch the American Americorps program and became the first executive director of Social Venture Partners Portland.

Spence is also president of Spence & Company, where he conducts training for professionals in a wide variety of industries, how to organize complex information for more effective communication. He previously served as research director for five years at Amana-Key, one of the leading executive firms in Brazil, and recently led a collaborative effort by Fortune 100 technical companies and their suppliers to improve sustainable supply chain management practices.