Microsoft offers an alternative to custom characters

- Transfer

In 1983, Alan Cooper, with a flick of his hand, awakened the first user character in design. Cooper, a software developer who laid the foundation for many new concepts, then just conducted a survey of a group of potential customers. He came to understand that by focusing on the motives of real users, rather than their own needs, it is possible to solve complex problems with great success. Later, in his critical analysis of design, Cooper began to model gestures, speech characteristics and the thought process of fictional individuals that were created based on the images of the people he interviewed.

The concept of characters quickly gained popularity both in the field of design and in development. And no wonder: they help us better understand what consumers need and predict how they will behave in situations where direct communication can be difficult.

But now we are beginning to realize what the negative side of the characters is. They are, by their nature, amalgamation, an averaged set of attributes that we attribute to our average user. But in reality, average users simply do not exist.

Artificial averaging and its consequences

In the 50s, the US Air Force conducted its famous study on the size of pilots. They took measurements of more than 4,000 people and calculated the average size based on 140 physical characteristics: height, chest circumference, and so on. Based on these 140 sets of measurements, a range of average values was established; it has been hypothesized that most pilots fall into this range. In fact, it turned out that among these four thousand there was not a single person who could meet the averaged values for all parameters.

Designing for the average pilot, thus, could potentially lead to deaths. The ergonomics of aircraft built on the basis of average dimensions were so useless that crash occurred because of this. These aircraft, which were made for everyone, in the endturned out to be unsuitable for anyone .

Conjecture-Based Design Dilemma

We repeat the same mistake every day in working on our products. We invent a character - let's call him Ted - give him different characteristics: for example, a family, a successful career, a house in the suburbs, two cars (you can see all this in the picture at the beginning of the article). Perhaps he even has a cat. After that, we begin to argue what Ted will like and what not. “Does it really seem to you that Teda will make a similar decision in the product? Personally, his profile tells me more about the opposite. ”

But in fact, no one really knows how to please Ted, simply because Ted does not really exist. Such a statement may seem banal, and yet, the problem is serious: the more we strive to “humanize” Ted, giving him new character traits and detailing habits, the stronger, without realizing it, we turn it into a stereotype. Carried away by this process, we confuse ourselves because we forget that we are talking about an abstract squeeze from the results of user research.

Worse, with each of these excessively small details with which we decorate the image of Ted, he reveals less and less similarity with the audience, based on which we design the product. With this approach to design, a non-existent person begins to overshadow and obliterate in our perception of real people. Often such Teds have the following characteristics: they are created somewhere in bunkers without a specific purpose, over time they remain static, do not change from one use case to another, and are based on artifacts that are useless for product designers and their teams.

Spectrum of characters: not fictional characters, but real motives

We need tools that could again bring to the product design process an awareness of how diverse our audience is. Each decision we make either creates additional barriers to activity in society to one or another group of people, or vice versa destroys them. Universal design focuses on the fact that our responsibilities include eliminating inconsistencies between people and products, the environment, and social structures. You should look for ways to check how versatile a particular design is, to take measurements and maintain balance.

So how do you put real users in first place without resorting to artificial constructs like the “average person”? One method is to destroy the characters (sorry, Ted!) And replace them with a model with spectra. With this approach, we do not try to outline a generalized person, but focus on a whole range of motives, contexts, opportunities and circumstances.

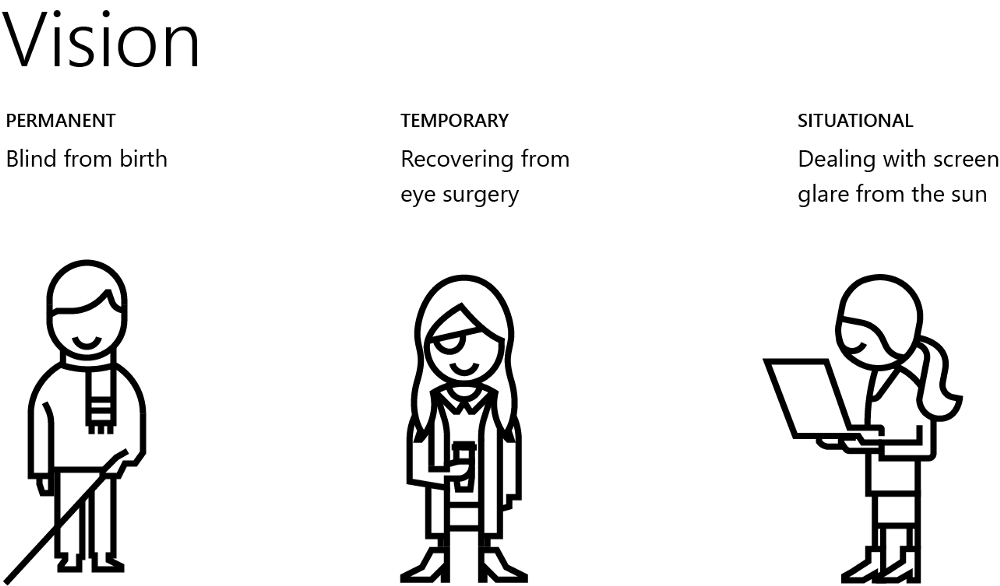

The range of characters is not an image of a fictional person. This is an expression of a certain motive, which people are guided by in their actions, and observation of the population groups in which it arises. In this way, we can track how motivation changes depending on the context. Some characteristics are unchanged, for example, in the case of a person who is blind from birth. At the same time, a patient who has recently undergone eye surgery may also experience temporary vision problems. And someone else will face the same barrier due to the specifics of the environment: say, the screen of his device will greatly glare when working in the open sun.

The spectra of the characters cannot be called an ideal technique, but nevertheless they help us build a user experience with great equality. They apply the strengths of the characters - their ability to turn abstract research results into something specific and humanized - but do not erase the diversity in individual characteristics. Designing in accordance with the range of needs and motives, we avoid the assumptions and biases that make up an integral part of any character. We customize the design for the interests of a large number of different users, rather than the abstract hypothetical Ted.

Spectra from an economic point of view

But the spectra of the characters are not only an exercise for empathy training. They also provide us with a business case. For example, let's imagine that you adapt a product to the needs of people with one hand. There are about twenty thousand of them in the USA. But if we add to this number also those who have a broken arm or damaged wrist, as well as those who, for one reason or another, have only one arm free (for example, young parents who carry a baby everywhere), you can easily reach a twenty millionth audience, even within the country.

The Microsoft Design team is now introducing a character spectrum model to work on a range of products. We are seriously reviewing the purpose of our characters and their limitations in order to create products for real people in real situations. With the help of spectra, we think through and iterate the design taking into account various physical, social, economic, temporal and cultural conditions.

Physical context

Different conditions open up different possibilities, introduce different restrictions and are associated with different rules and social norms. Here are some examples you can start with: Home - Out of town - In the library - In the car - In the city center - In the bus

Social context

Different social contexts prescribe different rules, norms and behaviors. Here are some examples you can start with: Alone - With colleagues - In a crowd - With family or friends

Temporal / situational constraints

Physical constraints are often temporary arising from a particular situation. On this card you can choose which restrictions are relevant for the situation in question: Does not see - Cannot speak - Does not hear - Cannot touch

Economic barriers

Budget is less than $ 10 - Lack of access to formal training and professional teachers - Minimum resources - Many students in the classroom

It is important to study the problem of universality and take people's needs into account from the very beginning. Gathering the opinions of real people who tell us about their motives, we can gradually grasp with understanding the whole range of human characteristics and introduce it into the product, creating a design that supports individuality and is based on those motives that unite us all. In the coming weeks, we plan to describe in more detail the process of forming our own spectrum. In the meantime, if you wish, you can familiarize yourself with our set of tools for creating a universal design.