What determines the interesting gameplay?

- Transfer

I think everyone will agree that the feelings from the gameplay in different games are different. Some games seem more “playable" than others. Just compare the game in Super Mario with something like Dear Esther, and it seems to me that the first one feels more gameplay than the last. What caused this feeling? My hypothesis is this: the difference in the possibility of planning .

The more a player can plan the game in advance, the more exciting it seems.

Before I provide evidence that this is most likely true, I need to give some background information. To understand why planning plays such an outstanding role in games, we need to look at the evolution of our species and answer the question: why are fish so stupid?

This is what the world usually looks like for fish:

They can see only 1-2 meters in front of them, and often the situation is even worse. This means that fish cannot make distant plans. They simply react to what appears before their eyes, and this is their whole life. If the life of the fish was a game, it would be a limited version of Guitar Hero with random noise instead of music. This is exactly what fishing happens. Pisces do not think like us, they are controlled by reactions with strictly defined logic.

Most of Earth’s history has been the life of organisms. But after that, about 400 million years of evolution passed . Fish began to move to land. Suddenly, the following picture appeared to their eyesight:

It changed their world. Suddenly, the opportunity arose to plan and correctly perceive your surroundings. The smart brain used to be a waste of energy, but now it has become a big advantage. In fact, this transition was so important that it probably became a significant factor in the evolution of consciousness. Malcolm MacIver, who, as I know, was the author of this theory, writes about it this way:

“But then, about 350 million years ago, in the Devonian period, animals such as tiktaalik began to make their first test raids on land. In terms of perception, it was a whole new world. We can see objects about ten thousand times better. Therefore, just sticking our eyes out of the water, our ancestors fell from the murky fog of the previous environment into a clearly visible world where they could observe the environment from a fairly considerable distance.

This put such first members of the “clearly seeing” club in a very interesting position from the point of view of evolutionary perspectives. Think of the first animal that received any mutation that separated its sensory input signals from motor reactions (up to this point, their instantaneous connection was necessary, because reactivity was required in order not to become someone's dinner). At this stage, they could potentially review several possible options for the future and choose the one that is most likely to lead to success. For example, instead of rushing straight to the gazelle, risking revealing your location too early, you can slowly sneak along the line of bushes (knowing that your future dinner also sees ten thousand times better than his ancestor who lived in the water) until you get closer. "

You can demonstrate the above with the following example:

This image perfectly shows the conceptual difference in the processes involved. One uses a linear process in which reactions occur along the way. In another, the animal explores the area in front of him, considers various approaches and selects the one that, with the available data, seems to be the best.

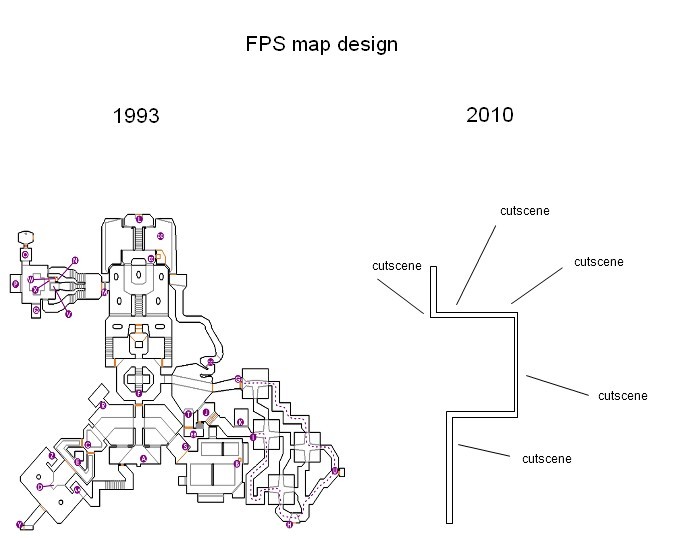

The analogy is not complete, but there is a striking similarity with the following image, showing the difference between the design of old-school and more modern FPS:

I know that this comparison is not entirely honest, but the important thing here is that when we look at these two images, it is obvious to us which of these two designs has better gameplay. The image on the left shows a more complex and interesting environment, and the right shows a linear sequence of events. And just as the world of fish is related to the world of animal land, this means a huge difference in the possibility of planning.

There are other interesting connections between the ability to see and plan. Malcolm Makiver answers the question about the intelligence of octopuses:

“It's amazing how these unprotected pieces of delicious protein survived under millions of years of constant threat. By the way, they have the largest of all known types of eyes (in the largest deep-sea species, the size reaches the diameter of a basketball). Obviously, they use them to recognize very distant silhouettes of whales (their greatest enemies), in the light reflected from the surface.

The theory develops the idea that the advantage of planning is proportional to the limit at which the creature can sense to the distance of movement during the reaction. The theory determines the period of our evolutionary past during which a large-scale change in this ratio took place, and suggests that such a change has become an important factor in the development of planning ability. Interestingly, octopuses and sprayers are usually motionless before performing their actions. This maximizes their relatively small area of sensory perception. In other words, for animals caught in the trap of a water mist, due to planning, there are other ways to increase the perception area relative to the distance of their movement. "

Sight, of course, is not the only reason that we humans have evolved to the current level of intelligence and consciousness. Other important factors were upright posture and our universal hands. Having risen to our feet, we were able to see better and use our hands more effectively. Hands are our main means of changing the world around us. They allowed us to create tools and change the environment in various ways to optimize survival. All these factors are inextricably linked with the possibility of planning. After we learned to change the world around us, the number of available options expanded and the complexity of our plans increased enormously.

But this did not end there. Planning is a critical part of our social life. Model of a person’s mental stateOur ability to imitate other people is both the reason and the result of our planning ability. Managing social groups has always been a very thorough process of thinking through various options for action and their consequences.

In addition, planning also underlies two other phenomena that were discussed in my blog earlier: mental models and the effect of presence . Mental models exist with us so that we evaluate actions before they are completed, which is obviously critical for planning. Presence is a phenomenon that occurs when we are included in our plans. We want to simulate what is happening not only in the world, but also with ourselves.

To summarize: there are many evolutionary reasons why planning has become the fundamental foundation of what made us human. It is a big part of who we are, and when we can use these abilities, we will certainly find it exciting and interesting.

Well, all this background information is very informative, but is there really reliable evidence that this applies to games? Yes, and actually quite serious! Let's look at what I find most interesting.

There is a player engagement model called PENS (Player Experience of Need Satisfaction), and it has been rigorously researched. To evaluate what a player thinks about the game, she uses the following criteria.

- Competence . How well the game satisfies our need for a sense of competence, a sense of mastery of the game.

- Independence . What level of freedom does the player have and what opportunities does he have for expressing it?

- Connectedness . How much is the desire of the player satisfied in common with other players?

Measuring how well the game performs in these metrics has proven to be a much better indicator of various aspects of success (sales, likelihood of people recommending the game, etc.) than simply asking if the game is “interesting”.

And, more importantly, two of the above factors are directly related to planning. Competence and independence are very tied to the player’s ability to plan. Let's explore why this is so.

In order for a player to feel competent in the game, he must have a deep understanding of how the game works. Of course, there are games in which simple reflexes are enough, but they are always very primitive. Even in most music games, the player needs to learn and understand in order to play better. An important part is also remembering the melodies of each level. Why? For the optimal location of the "manipulators" of the input (whether fingers or feet), to get into as many notes as possible. All these aspects come down to one thing: the ability to predict the future.

We see the same thing in most games. The player begins to play better in Dark Souls when he understands how monsters attack, what is the level scheme and how his own attacks work. Learning the work of the world and gaining the ability to predict is the cornerstone of competency. Of course, the player needs to develop motor skills to perform the necessary actions, but this is almost always less important than understanding when and why actions are needed. A simple prediction ability is not enough, you must also have a sense of what goal the player wants to achieve, and use the prediction ability to complete the steps required to achieve it. Or, in other words: the player needs to plan.

Independence also depends heavily on planning ability. Imagine a game in which you have a large degree of freedom, but you absolutely do not understand how the game works. Everyone who runs a complex strategy game without an understanding of the basics knows that this is not very exciting. For freedom to mean something, you need to have an idea of what to do with it. You need to understand how the mechanics of the game behave, what tools are at your disposal, what goals you want to achieve. Without this, freedom is confusing and meaningless.

To ensure a sense of independence, the game should not only provide a large space of opportunities, but also teach the player how the world works and what the role of the player is in it. The player must be able to model in consciousness the various actions that can occur, and to come up with consequences that can be used to achieve a specific goal. When you have these opportunities, then you have the freedom that is worth having. It is probably pretty obvious that I'm talking about the ability to plan again. A world in which a player cannot plan is a world with little independence.

Similarly, if the game has only a linear sequence of events, then there is not much to plan. In order for a player to make plans, he must have options. This does not apply to cases where only a certain chain of actions is possible. Such cases are a typical example of a lack of freedom, and they do not satisfy the player in terms of freedom. I repeat - planning and independence are connected in very sophisticated ways.

It can also be proved that the connectedness factor also relates to planning. As I explained above, any social interactions are highly dependent on our ability to plan. However, I do not think that the dependence is not so strict, and the first two aspects are quite enough. So let's take a better look at the evidence from a different angle.

In games, there is a long-term trend - the addition of new "meta" -functions. Such a very common feature today is crafting, and in most major games it is present to some extent. RPG-like level-up elements are also widely used, not only for characters, but also for resources with weapons. Still often there is a collection of money that can be used to purchase various items. Look at almost any recent game and you will definitely find at least one of these features.

So why are they being added to games? The answer is quite simple: they make the game more exciting. Why this happens is a bit more complicated question. This cannot be only because it gives the player more options. If this were so, then games with random variations of mini-games would appear, giving the gameplay some sharpness. But instead, we see constantly used strictly defined types of functions.

My theory is that it has to do with planning. The main reason for adding such functions is that they expand the space of planning opportunities and provide more tools that can be included in planning. For example, collecting money in combination with having a store means that the player will have a goal - to buy a certain item. Collecting the right amount of money with the intention of exchanging it for goods is a plan. If the desired item and method of collecting coins is connected to the main gameplay cycle, then this meta-function will give the feeling that the main cycle has more planning than it actually is.

These additional features can also enhance the gameplay. Remember how you need to think about which weapon to use in The Last of Us. The player has garbage from which you can craft items, and all these items allow you to use various tactics in battle. And since it is impossible to apply them all at the same time, the player needs to make a choice. Making such a decision is always creating a plan, so the sense of involvement in the game intensifies.

Whatever your attitude towards these types of meta-functions, there is no doubt one thing: they work. Because if they did not work, then their popularity would not grow and would not last so long. Of course, you can create a game with a lot of planning and without using these functions. But it will be a more difficult way. Adding these features is a well-proven way to increase engagement, so using them is very tempting, especially if you can lose to your competitors if they aren't there.

And finally, I want to talk about what actually led me to thinking about planning. It began with the fact that I began to compare SOMA with Amnesia: The Dark Descent. When creating SOMA, it was very important for us to add as many interesting features as possible, and we wanted the player to have a lot of different activities. I think it’s fair to say that SOMA has a wider range of interactions and greater variability than Amnesia: The Dark Descent. But despite this, many people complained that SOMA was too much like a walking simulator. I can’t recall a single similar comment about Amnesia. Why did this happen?

At first I could not understand this, but then I highlighted the main differences between these games:

- The state of mind in Amnesia.

- Lighting / Health Resource Management.

- Puzzles distributed at different levels.

All these aspects are directly related to the player’s ability to plan. The mental health system means that the player must think about what routes to go, whether he should look at monsters and so on. Such moments the player needs to consider when moving around the level and they provide a constant need for creating plans.

The resource management system works in a similar way: the player also needs to think about when and where to use the resources available to him. She also adds another layer, because the player becomes clearer what types of objects he will find on the map. When a player enters a room and pulls out boxes, this is not just useless action. The player knows that some of the boxes have useful items, and a room search becomes part of a larger plan.

In Amnesia, the design of many levels is built around a large puzzle (for example, the launch of an elevator), which is solved by performing a set of scattered level and often interconnected puzzles. Due to the scattered puzzles in the rooms, the player needs to make a decision about where to go next. It is impossible to complete the game simply by using the "visit all rooms" algorithm. You need to think about which parts of the level you need to return to, and which puzzles are left to solve. This is not very difficult, but enough to create a sense of planning.

SOMA does not have any of these functions, and not a single new function makes up for the lack of planning. This means that the game as a whole creates a feeling of less gameplay, and for some players it seemed like a transition to the territory of “walking simulators”. If we knew the importance of planning ability, we would take some action to solve this problem.

A “regular” game using a standard core gameplay cycle does not have such problems. The ability to plan is built into the image of the implementation of the classic gameplay. Of course, this knowledge can be used to make such games better, but this is by no means necessary. I think it is for this reason that planning as a fundamental aspect of games is so underestimated. The only good example I could find [1] is this article by Doug Church, where he explains everything as follows:

“This simple, logical control, combined with very predictable physics (clear for the Mario world) allows players to make the correct assumptions about what will happen in their actions. The complexity of monsters and environments increases, but new and special elements are introduced gradually, and are usually built on the existing principle of interaction. This makes the game situations clearly expressed - it is very easy for players to plan actions. If players see a high ledge that gets in the way of a monster or a chest under water, they begin to think about what to do with them.

This allows players to participate in a rather sophisticated planning process. They are introduced (usually indirectly) to how the world works, how they can move and interact with the world, what obstacles they must overcome. Then, often subconsciously, they change the plan to get where they want. During the game, players create thousands of such small plans, some of which work, and some do not. The important thing is that when the plan fails, the players understand why this happened. The world is so holistic that it immediately becomes apparent why the plan did not work. ”

This is a real hit on the spot, an excellent description of what I was talking about. The article is from 1999, and it was difficult for me to find other sources discussing it, not to mention the development of this thought from that time. Of course, we can say that planning is described in Sid Meyer's phrase “A sequence of interesting choices,” but to me it seems too vague. It is not entirely about the aspect of predicting the mechanics of the world and creating plans based on this knowledge.

The only case that approximates this principle is the discussion of the Immersive Sim genre. Perhaps this is not very surprising, the Doug Church chain played a big role in the development of this genre. For example, the unforeseen gameplay, which immersion simulators are especially famous for, is strongly associated with the ability to understand the world and plan actions based on this information. This type of design ideal is clearly visible in modern games like Dishonored 2 [2]. Therefore, it is pretty obvious what game designers think in this coordinate system. But for me it is much less obvious why this is considered not as a fundamental part of what makes the games fun, but as a kind of subset of the design.

As I mentioned above, perhaps this happens because when you participate in the "usual" gameplay, a large amount of planning occurs automatically. However, this does not apply to the case of narrative games. In fact, narrative games are often considered “not entirely games” in that they do not contain much conventional gameplay compared to games like Super Mario. For this reason, it is often discussed whether games should have more history or gameplay, as if they were necessarily mutually exclusive. However, I believe that the reason for the persistence of such a big discrepancy is that we do not quite correctly understand how the gameplay works in narrative games. As I said in previous posts , in terms of design, we are stuck at local highs.

The idea that planning is the fundamental foundation of games gives us a solution to this problem. We will not say: “narrative games need better gameplay”, say: “narrative games need better planning”.

To fully understand what we need to do with planning, we need some basic theory to give it all a meaning. The SSM framework I introduced recently is well suited for this role.

To understand in detail, it is better to read a recent post , but for completeness, I will briefly talk about the framework here.

We can divide the game into three separate spaces. Firstly, to the system space. All code belongs to it and all modeling is carried out in it. The space of the system works with all components as with abstract symbols and algorithms. Secondly, we have a space of history that provides a context for events taking place in the space of the system. In the space of the system, the character of Mario is just a set of collision boundaries, but when this abstract information is passed through the space of history, it turns into an Italian plumber. And finally, we have the space of the mental model. It represents how the player thinks about the game and is a kind of mental cast of everything that exists in the game world. However, since the player almost never knows exactly what what happens in the space of the system (and how to interpret the context of history) is just a reasonable assumption. In the end, the mental model is what the player uses to play the game and on which he bases his decisions.

With all that said, we can begin to create a definition of what the gameplay is. First, we need to discuss the concept of action. In essence, an action is all that a player does during the game, and it consists of the following steps:

- Evaluation of information obtained from the spaces of the system and history.

- Creating a mental model based on available information.

- Modeling the consequences of performing a certain action.

- If the consequences look good, send the game the appropriate input (for example, pressing a button).

Much of this happens subconsciously. From the player’s point of view, he sees this sequence mainly as “doing something” and is not aware of the ongoing mental process. But in fact, it always happens when a player does something in the game, whether it's jumping through the abyss in Super Mario or building a house in Sim City.

Having figured out what such an action is, we can move on to the gameplay. This is a combination of many actions, but with one exception: we do not send input to the game, but simply imagine that we are doing this. Therefore, the chain of actions in the space of the mental model is joined together, evaluated, and only then does the player begin to send the necessary input data if the results look satisfactory.

In other words: the gameplay consists entirely in the planning and subsequent implementation of the plan. And based on all the evidence presented above, my hypothesis is this: the more actions you can combine together, the better the gameplay seems.

It is not enough to simply combine any actions together and call it a plan. Firstly, the player needs the idea of some goal that he is trying to achieve. In addition, actions should be non-trivial. Simply combining a set of walking actions will not be exciting for the player. It is also worth pointing out that planning is by no means the only aspect affecting involvement in the game. You cannot frame all other design elements simply because the player is focused on planning.

However, there are many design principles that go hand in hand with planning. For example, having a holistic world is critical, because otherwise the player will not be able to plan. That is why invisible walls are so annoying: they make it very difficult to create and execute plans. It also explains why players are annoyed by seemingly random setbacks. For the gameplay to feel good, we need to be able to mentally model where the error occurred. As Doug Church said in the quote above: if a player loses, then he needs to know why.

Another example is a tip for adventure game authors: there should always be several puzzles at the same time. From the point of view of planning, this is necessary because it is necessary to provide the player with space for the possibility of planning: "First I will solve this riddle, and then this." There are many other principles related to planning. Although planning is not the only aspect that makes the game exciting, you can extract many useful elements from it.

Let's take a quick look at real-life examples from real games.

Suppose in this situation the player wants to kill the enemy in red. Player notwill just jump and hope for the best. Before starting, he needs to come up with some kind of plan. He can first wait for the guard to leave, teleport behind the victim's back, sneak up and stab him. After that, he will leave the place in the same way. This is what the player thinks out before taking any action. He does not take action until he comes up with a plan.

This plan may not work, for example, the player will not be able to sneak up on the enemy and he will raise an alarm. The failure of the plan does not mean that it was completely wrong. It just means that he was unable to complete one of the actions. If you show this correctly, the player will not experience disappointment. In addition, the player may misinterpret his mental model or miss something. This also suits him if he has the ability to change the mental model accordingly. And the next time the player tries to implement a similar plan, he will cope with it more successfully.

Often this ability to fulfill our plans is the most exciting in the game. Usually the game is a little slow at first, because the mental model has not yet been created, and the planning ability is not very well developed. But in the process of the game, it gets better, the player begins to combine longer sequences of actions together and therefore gets more pleasure. This is why learning levels can be so important. This is a great way to get rid of the initial slowness. Training simplifies the gameplay and allows the player to reason correctly about how the game works.

It is also worth noting that plans should never be too easy to implement, otherwise actions become trivial. To maintain involvement in the game, a certain degree of non-triviality must always remain.

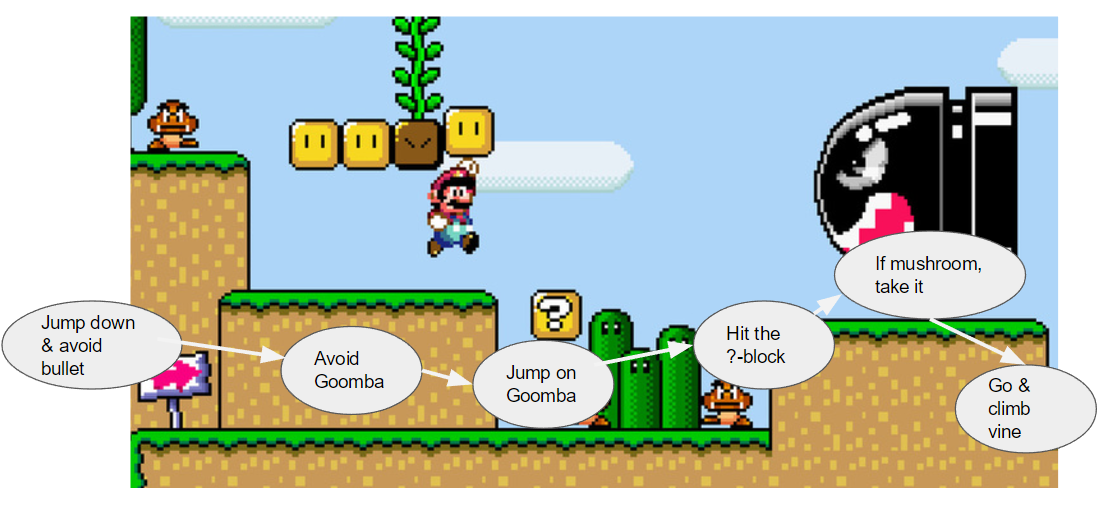

Planning does not always have to be long-term; it can be very brief. Take this scene from Super Mario as an example:

Here, the player needs to make a plan in a split second. It is important to note that the player is not just blindly reacting. Even in a tense situation, if the game works as it should, the player quickly formulates a plan, and then tries to implement it.

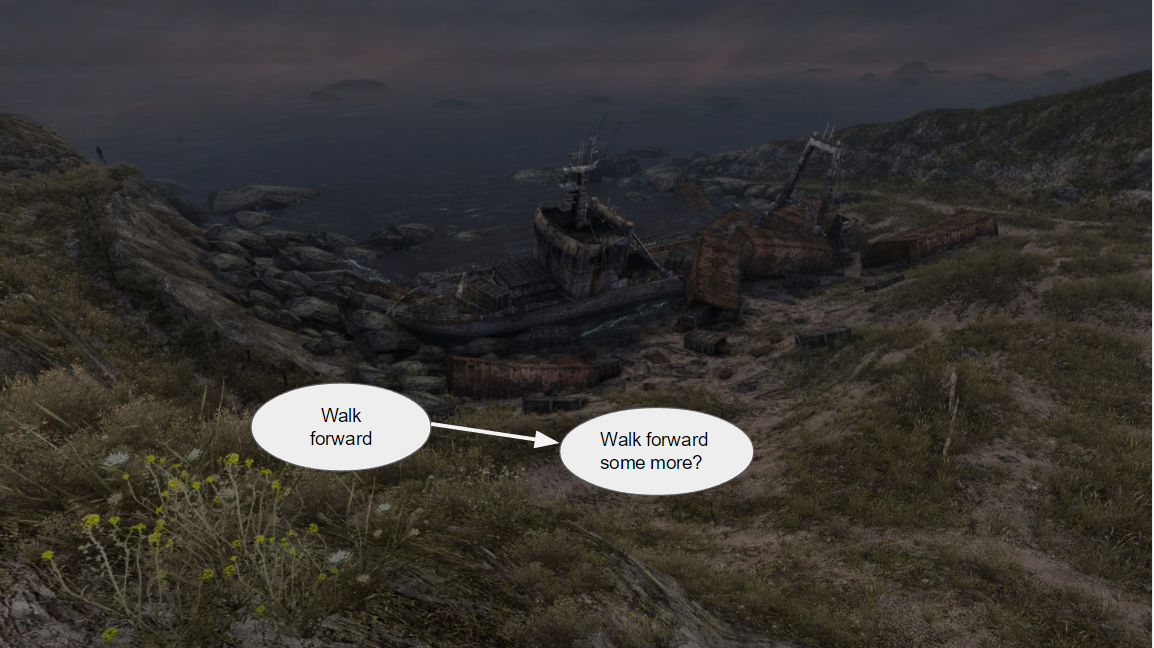

Now compare these two examples with a game like Dear Esther:

In this game a lot can be liked, but, it seems to me, everyone will agree that there is not enough gameplay there. It is more difficult to agree on what is missing there. I heard a lot about the impossibility of losing and the lack of competitive mechanics, but it does not seem convincing to me. As you probably guessed, I think that there is no planning here.

The main reason Dear Esther is considered unappealing is not that you cannot lose or fight with anyone. The game simply does not allow players to create and execute plans. We need to find a way to solve this problem.

Approaching the planning within the framework of the SSM framework , we can understand what type of gameplay can be contained in a “narrative game”: when creating a plan in the space of the mental model, it is important that the actions are mostly based on data obtained from the space of history.

Compare the following two plans:

1) “First, I will collect 10 items to increase the confidence of character X,

which will allow me to achieve the necessary indicator of“ friendship ”, after which X will become part of my team. This will give me a bonus of 10 ranged points. "

2) “If I help X with cleaning the room, then we can become friends with her. It will be wonderful, because then I can invite her on a journey with us. She seems to be a good shooter, and with her I will feel much calmer. "

This is a pretty primitive example, but I hope my point is clear. Both of these approaches describe the same plan, but they are very different in terms of data interpretation. Number 1 occurs in the abstract space of the system, while number 2 is felt to be more narrative and based on the space of history. When the gameplay consists in creating plans similar to the second, then something begins to appear in us that feels like a truly narrative gameplay. This is a critical step in the development of the art of interactive storytelling.

I believe that planning thinking is a crucial step towards creating deeper narrative games. For too long, game design has relied on a planning component that emerges naturally from “standard gameplay,” but now that we no longer have it, we need to pay special attention to it. You need to understand what controls the gameplay and make sure that these elements are present in the narrative gameplay. Planning is by no means a “silver bullet,” but it is a really important ingredient. And when developing future games of Frictional Games, we will definitely think a lot about it.

Notes:

1) If someone has other solid sources that describe planning as a fundamental part of games, I would love to hear about them.

2) Steve Lee held an excellent lecture at the GDC this year, “Approaching an Integrated Level Design,” where we talked a lot about the intentionality of player actions. This is another concept closely related to planning.