How to write an IO monad in C # (not) without the help of a parallel universe and a time machine

In life, there are often situations when you just need to sit down and do something, without bothering yourself with questions like "what will it give?", "And who needs it?" etc. The writing of the monad is

Monad Interpretations

There are two ways to understand (interpret) the monad.

The first interpretation can be found, for example, in the wonderful IO inside article . Although this is not explicitly declared, this article

The second interpretation can be understood by noting that for other monads (for example,

None of these interpretations helps to translate the concept

Obviously, the problem is uniqueness

Let us (within a certain programming language) have a function

At first glance, it seems that it is

However, when using a pure function

But it immediately follows from here that not only is it clean,

In accordance with the foregoing, it is not impossible that when executing a program consisting of pure functions only, that which should be displayed and read that should be read - that is, that the computer behaves as if ours Programs have a side effect, although they are not. Moreover, the provision of such activity is shifted from our shoulders - the shoulders of the applied programmer - to the shoulders of the developers of the executor; that is, on the aggregate virtual shoulders of the developers of the microprocessor, compiler, Haskell runtime and all that.

What remains to be done in the program code is to make sure that the necessary letters are displayed on the screen and find out which ones are entered. And for this we need a time machine and a parallel universe.

The idea is to serialize the Universe (everything that was, is and will be), then encode (for convenience) in base64 and include it in our program as a hard-coded string constant. In fact, I am not sure both of the need for the indicated set (time machine + parallel universe), and of its sufficiency. However, in my opinion, it will not be possible to do without a parallel universe, since serializing the universe while being in this universe itself will probably be more difficult than writing quin on the POSIX shell.

Of course, in order for the program to Haskell(which is a pure function) could extract information related to the specific launch (instance) of this program from the constant of the Universe, it should take some identifier of this instance as an input. And she really accepts it - in the form of a type value

Acting in this way, it is not difficult to create a library of pure I / O functions. Function signatures can be, for example, such (for simplicity we restrict ourselves to the simplest console input-output of strings):

The function

In fact, it turns out that instead of a function,

Despite the fact that it is difficult to bring the ideas described above to a working code for our Universe, you can do this for a simple model universe.

So, let there be some universe in which some creature named noname lives. Noname studies at the university with a degree in computer science, and to pass the state exam in programming, he needs to write a project - a console program that asks the user for a name, reads the answer and displays a greeting:

The only programming language in this universe is Haskell , with no built-in monad support

For historical reasons, the main function and module in this universe are called, respectively,

Noname checked the functionality of the program by running it and entering its name - and the program seemed to work as it should - asked for the name and in response to "noname" issued "Hi, noname!"

(As you can see in the program there are no explicit indications of what exactly display and at what moments wait for user input, so the fact that this program is working is very indicative in the sense of demonstrating the power of heuristics embedded in the standard Haskell rantimeof the noname universe.)

However, despite the fact that the program worked correctly during the first test run, noname is not sure that the program will continue to work: after all,

Running this universe program as it is, of course, will not work. But if you provide it with the following starting module, then somehow it will work:

(Полный проект лежит на гитхабе: pure-io. Кстати если вы всё ещё не знаете, как управляться с инструментом сборки проекта и управления зависимостями stack, который пришёл на смену cabal, то вот хорошая статья: Прощай, cabal. Здравствуй, stack!.)

Конечно, мы не увидим «выводимых» сообщений, равно как и не сможем ввести имя, потому что у нас нет умного иновселенского райнтайма — лишь запись соответствующего диалога, возвращаемая функцией

Having understood the principle of the program and built a time machine according to the drawings provided, it is easy to make sure that you

Having dealt with the principle of pure non-monadic I / O in this way and providing fraternal assistance to the noname invader, we will move from the model universe to the real one and from Haskell to C # .

Due to the existence of the mechanism of executions C # - a function that returns

Given the aforementioned situation with executions, we will choose such signature blanks of our pure I / O functions:

A function

These functions are pure, so it would be possible to express them through other pure functions (as was shown in the previous section), but instead we will go the other way. Namely, we will create an equivalent native implementation - thanks to this we will not need parallel universes and time machines.

Let's see if it is possible to somehow refactor and improve the external syntax of these functions without violating ideology. You can make them non-static members

Using

Further, you can notice that the first function is the functional equivalent

Finally, we rearrange the parameters for convenience and give the methods the same short name to emphasize symmetry:

Such unification is justified by the fact that if it

Prepare the test environment:

Let's start with a simple one:

Note that not only the performance of a pure function,

Let's try something more interesting. For example, we rearrange the calls

A pure function should return the same result on the same set of arguments:

If the conclusion failed for some reason, we should get an error in the form of execution:

We also need at least one read test:

We write an auxiliary class that will parse the passed linq expression and make a real call to the specified method with the specified parameters, using the passed

To track the same calls (as in the test

Now we can reduce two methods

It remains to implement the last method - and the thing is done.

It is clear that we need to somehow cache the results of our calls to the native console. Add the necessary classes and fields:

Having done the preparatory work, we can finally write actually

The algorithm is simple. If a request comes about the result of an already completed operation, then we go into the cache and check IOOperation. If we have a complete match, it means that the specified method was actually called with the specified parameters, and we return the result; and if there is a difference, the raise is quick. Further, if there is no operation in the cache yet and now is the right time to perform it, we perform the operation, add it to the cache along with the result, and return the result. If there is no operation in the cache and a time machine is required to perform it, nothing good will come of it, so it remains to fall by raising a special flag in advance

Such a simple implementation behaves in the same way as a possible implementation on pure functions, and ensures passing written (and unwritten) tests.

Monad

Now that we have pure non-monadic I / O functions, writing a monad

We can even support the special monadic syntax available in C #.

In addition to those mentioned, we added a very useful method

You will also need a “monad” entry point to the application:

Let's write the simplest console application using the monad

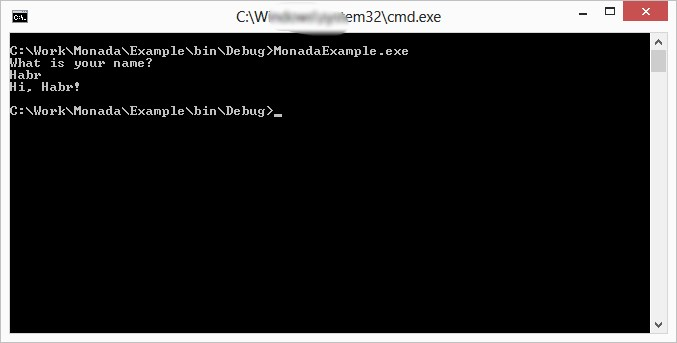

Result of work:

Full code on github: IOMonad .

IO —certainly just such a case. Therefore, under the cat there is a story about how to write a monad IOin C #, without the slightest attempt to explain why .Accordion picture reflecting the essence of the article

Monad Interpretations IO

There are two ways to understand (interpret) the monad.

IO.The first interpretation can be found, for example, in the wonderful IO inside article . Although this is not explicitly declared, this article

IOconsiders it as a way to trick the Haskell compiler into shoving calls to dirty functions into clean code due to the possibility of formally treating them like clean ones by adding dummy elements to the signature. The second interpretation can be understood by noting that for other monads (for example,

Getfrom a module Data.Binary) there are functions of the type m a -> a(for Getthis it is a function runGet), that is, it is possible to extract a value from the monad. ForIOthere is no such function, and the only way to execute it is to return the mainnative runtime from the function . That is IO, it is a list of actions (a script), and the task of clean code is to create this list of actions, but not to perform them. None of these interpretations helps to translate the concept

IOinto C # : in the first case, we notice that in C # there is no difficulty calling the dirty code from anywhere, and in the second that in C # all functions and the program as a whole are a list of actions, and a semicolon is nothing more than a monad operator >>=. Obviously, the problem is uniqueness

IO: while other monads are syntactic sugar, input-output is an operation that is difficult to carry out, remaining within the framework of clean code. And if you find a way to write really clean (without monads, without directly or indirectly calling native functions) code that implements I / O, then it IOwill simply appear as syntactic sugar for these pure functions, an object of the same kind as a monad Maybe. Well, only lazy did not write Maybein C # .Pure Haskell I / O functions . Operating principle

Let us (within a certain programming language) have a function

beep,that returns the number 7 and displays the message “Beep!” And another function returnBeepthat simply returns the number 7. What can be said about the purity of these functions? At first glance, it seems that it is

returnBeeppure, but beepnot: pure function is a function that does not give side effects, and in the latter case, there is clearly a side effect. However, when using a pure function

returnBeepin a program, it must be calculated, and side effects in the calculation will also be present, at least in the form of heat dissipated by the computer. But does this mean that the functionreturnBeepceased to be clean because of this? This question can be answered in different ways and - just like in the case of the question “do parallel lines intersect?” - any of the answers can be taken as an axiom and build on this a consistent theory that allows you to create a model of some part of the world. So we will take it as an axiom that the implementation features of the calculator and, in particular, the side effects it creates when calculating the function do not affect the purity of the calculated function . But it immediately follows from here that not only is it clean,

returnBeep,but also beep,since the output of the message does not affect the course of program execution in any way, and therefore it is the same feature of the calculator implementation.In accordance with the foregoing, it is not impossible that when executing a program consisting of pure functions only, that which should be displayed and read that should be read - that is, that the computer behaves as if ours Programs have a side effect, although they are not. Moreover, the provision of such activity is shifted from our shoulders - the shoulders of the applied programmer - to the shoulders of the developers of the executor; that is, on the aggregate virtual shoulders of the developers of the microprocessor, compiler, Haskell runtime and all that.

What remains to be done in the program code is to make sure that the necessary letters are displayed on the screen and find out which ones are entered. And for this we need a time machine and a parallel universe.

The idea is to serialize the Universe (everything that was, is and will be), then encode (for convenience) in base64 and include it in our program as a hard-coded string constant. In fact, I am not sure both of the need for the indicated set (time machine + parallel universe), and of its sufficiency. However, in my opinion, it will not be possible to do without a parallel universe, since serializing the universe while being in this universe itself will probably be more difficult than writing quin on the POSIX shell.

Of course, in order for the program to Haskell(which is a pure function) could extract information related to the specific launch (instance) of this program from the constant of the Universe, it should take some identifier of this instance as an input. And she really accepts it - in the form of a type value

RealWorld(see the already mentioned IO inside article ). It is not possible to directly work with values of this type in Haskell , but it is not difficult to turn a type RealWorldvalue into a value of a type Integer,Stringor any other using the standard functions available. The specific type and method of conversion depends on the encoding of the constant of the Universe and the implementation of the input-output functions.Acting in this way, it is not difficult to create a library of pure I / O functions. Function signatures can be, for example, such (for simplicity we restrict ourselves to the simplest console input-output of strings):

getOutText :: AppInstance -> IOIndex -> Maybe String

getInText :: AppInstance -> IOIndex -> Maybe String

The function

getOutTextaccepts the application instance and text number in the user-program dialog and returns the corresponding text output by the computer or Nothingif the input parameters are incorrect. The result is Nothingreturned, for example, if the transmitted number corresponds to the text entered by the user and not the text displayed by the computer. So, if the specified instance of the program did not output anything, then for any number value the Nothing.function should return. The function getInTexttakes the same arguments and returns the corresponding text entered by the user either Nothing. In fact, it turns out that instead of a function,

getOutTextit is more convenient to use a more limited, but sufficient for practical needs, function isOutTextEqualswith the following signature and semantics:isOutTextEquals :: String -> AppInstance -> IOIndex -> Bool

isOutTextEquals text inst index = getOutText inst index == Just text

Pure Haskell I / O functions . Model implementation

Despite the fact that it is difficult to bring the ideas described above to a working code for our Universe, you can do this for a simple model universe.

So, let there be some universe in which some creature named noname lives. Noname studies at the university with a degree in computer science, and to pass the state exam in programming, he needs to write a project - a console program that asks the user for a name, reads the answer and displays a greeting:

What is your name?ВасяHi, Вася!

The only programming language in this universe is Haskell , with no built-in monad support

IO. The program prefab created by noname looks like this:The code

module Main_ where

import Control.Monad

import Data.Vector (Vector, (!?))

import qualified Data.ByteString.Lazy.UTF8 as U

import Data.ByteString.Base64.Lazy

worldBase64 :: String

worldBase64

= "V29ybGQge2FwcEluc3RhbmNlcyA9IFtbSU9PcGVyYXRpb24gSU9Xcml0ZSAiV2hhdCBpcyB5b3Vy"

++ "IG5hbWU/CiIsSU9PcGVyYXRpb24gSU9SZWFkICJub25hbWUiLElPT3BlcmF0aW9uIElPV3JpdGUg"

++ "IkhpLCBub25hbWUhCiJdLFtJT09wZXJhdGlvbiBJT1dyaXRlICJXaGF0IGlzIHlvdXIgbmFtZT8K"

++ "IixJT09wZXJhdGlvbiBJT1JlYWQgIlwxMDQyXDEwNzJcMTA4OVwxMTAzIixJT09wZXJhdGlvbiBJ"

++ "T1dyaXRlICJIaSwgXDEwNDJcMTA3MlwxMDg5XDExMDMhCiJdLFtJT09wZXJhdGlvbiBJT1dyaXRl"

++ "ICJXaGF0IGlzIHlvdXIgbmFtZT8KIixJT09wZXJhdGlvbiBJT1JlYWQgIlwxMDU0XDEwODNcMTEw"

++ "MyIsSU9PcGVyYXRpb24gSU9Xcml0ZSAiSGksIFwxMDU0XDEwODNcMTEwMyEKIl1dfQo="

type AppInstance = Int

type IOIndex = Int

data IOAction = IORead | IOWrite deriving (Eq, Show, Read)

data IOOperation = IOOperation IOAction String deriving (Show, Read)

data World = World { appInstances :: Vector (Vector IOOperation) } deriving (Show, Read)

world :: World

world = read $ U.toString $ decodeLenient $ U.fromString worldBase64

getInOutText :: IOAction -> AppInstance -> IOIndex -> Maybe String

getInOutText action app i = do

IOOperation actual_action result <- (!? i) <=< (!? app) $ appInstances world

if actual_action == action then return result else Nothing

getInText :: AppInstance -> IOIndex -> Maybe String

getInText = getInOutText IORead

getOutText :: AppInstance -> IOIndex -> Maybe String

getOutText = getInOutText IOWrite

isOutTextEquals :: String -> AppInstance -> IOIndex -> Bool

isOutTextEquals text inst index = getOutText inst index == Just text

_main :: AppInstance -> Maybe String

_main app = do

let question = "What is your name?\n"

_ <- if isOutTextEquals question app 0 then return () else Nothing

name <- getInText app 1

let greeting = "Hi, " ++ name ++ "!\n"

_ <- if isOutTextEquals greeting app 2 then return () else Nothing

return $ question ++ name ++ "\n" ++ greeting

For historical reasons, the main function and module in this universe are called, respectively,

Main_and _main, and, as you can see, the function _mainhas a type AppInstance -> Maybe String. In the implementation, noname _mainreturns a dialogue protocol - this is not required by the conditions of the task, but it can be useful for debugging purposes. Noname checked the functionality of the program by running it and entering its name - and the program seemed to work as it should - asked for the name and in response to "noname" issued "Hi, noname!"

(As you can see in the program there are no explicit indications of what exactly display and at what moments wait for user input, so the fact that this program is working is very indicative in the sense of demonstrating the power of heuristics embedded in the standard Haskell rantimeof the noname universe.)

However, despite the fact that the program worked correctly during the first test run, noname is not sure that the program will continue to work: after all,

worldBase64he entered the “constant of the universe” ( ) because he does not know the real one. Therefore, noname developed a time machine (of an original design, with a rather powerful suppressor of paradoxes built-in) and got in touch with our Universe, passing a listing of programs and drawings of a time machine in exchange for a promise to provide it with the exact constant of its universe (more precisely, the part of interest to it) - , they say, it’s more visible from here than to him from the inside. Running this universe program as it is, of course, will not work. But if you provide it with the following starting module, then somehow it will work:

The code

module Main where

import System.Environment

import Data.Vector ((!?))

import qualified Data.Vector as V hiding ((!?))

import Main_

main :: IO ()

main = do

args <- V.fromList <$> getArgs

case _main =<< read <$> (args !? 0) of

Just text -> putStr text

Nothing -> putStrLn "Error!"

(Полный проект лежит на гитхабе: pure-io. Кстати если вы всё ещё не знаете, как управляться с инструментом сборки проекта и управления зависимостями stack, который пришёл на смену cabal, то вот хорошая статья: Прощай, cabal. Здравствуй, stack!.)

Конечно, мы не увидим «выводимых» сообщений, равно как и не сможем ввести имя, потому что у нас нет умного иновселенского райнтайма — лишь запись соответствующего диалога, возвращаемая функцией

_main, будет нам доступна. Передавать номер запуска (AppInstance) также придётся вручную — аргументом командной строки, но этого достаточно, чтобы понять и смоделировать функционирование этой программы в её реальном окружении.Having understood the principle of the program and built a time machine according to the drawings provided, it is easy to make sure that you

wordBase64do not need to correct the constant : the program will be launched only three times (counting the first test run), and the author will run it all three times by entering the very names that he from the very beginning encoded in the text of the program! Having dealt with the principle of pure non-monadic I / O in this way and providing fraternal assistance to the noname invader, we will move from the model universe to the real one and from Haskell to C # .

Pure I / O functions in C #. Interface

Due to the existence of the mechanism of executions C # - a function that returns

X,in fact returns Either Exception X; in particular, void-functions “return” Either Exception ().(By the way, in Haskell the situation is similar, and the conditional definition of the standard there IO, taking into account the presence of executions, does not look like, type IO a = RealWorld -> (RealWorld, a),but rather how type IO a = RealWorld -> (RealWorld, Either SomeException a).). Given the aforementioned situation with executions, we will choose such signature blanks of our pure I / O functions:

static void AssertOutTextEquals(string text, AppInstance inst, int index);

static string GetInText(AppInstance inst, int index);

A function

AssertOutTextEqualsis the same isOutTextEquals,only instead Trueit returns voidwithout an action, but instead it Falsethrows an action. Similarly, a function GetInTexteither returns a nonzero string or throws an execution. These functions are pure, so it would be possible to express them through other pure functions (as was shown in the previous section), but instead we will go the other way. Namely, we will create an equivalent native implementation - thanks to this we will not need parallel universes and time machines.

Let's see if it is possible to somehow refactor and improve the external syntax of these functions without violating ideology. You can make them non-static members

AppInstance, and also use voidsomething more idiomatic instead (for functional code):public sealed class None {

public static None _ { get { return null; } }

None() { }

}

public sealed class AppInstance {

public None AssertOutTextEquals(string text, int index);

publi string GetInText(int index);

}

Using

Noneinstead voidwill avoid unnecessary duplication of code and make it easier to write the actual monad. Further, you can notice that the first function is the functional equivalent

Console.Write(string),and the second - Console.ReadLine().In addition to these, the class Consolehas many more useful input and output functions and, using linq expressions, we can generalize our pure functions to support all of them at once:public None AssertOutTextEquals(Expression ioExpression, int index);

public TResult GetInText(Expression> ioExpression, int index);

Finally, we rearrange the parameters for convenience and give the methods the same short name to emphasize symmetry:

public None AssertIO(int index, Expression ioExpression);

public TResult AssertIO(int index, Expression> ioExpression);

Such unification is justified by the fact that if it

Nonewere part of the standard ecosystem, then instead of Actionus we would have the first function would disappear as a special case of the second.

In order for us to write unit tests, it is necessary to provide the ability to work not only with a real console, but also with a test replacement:FuncThe code

public sealed class AppInstance {

readonly static Lazy inst = new Lazy(() => new AppInstance((method, argTypes, args) => typeof(Console).GetMethod(method, BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.Public, null, argTypes, null).Invoke(null, args)));

public static AppInstance Get() { return inst.Value; }

readonly Func consoleDescriptor;

internal AppInstance(Func consoleDescriptor) {

this.consoleDescriptor = consoleDescriptor;

}

}

public static class AppInstanceTestExtensions {

public static AppInstance ForTests(this AppInstance inst, Func consoleDescriptor) {

return new AppInstance(consoleDescriptor);

}

}

Prepare the test environment:

The code

[TestFixture]

public class Tests {

TestConsole console;

AppInstance testInst;

protected void Setup(string input) {

console = new TestConsole(input);

testInst = AppInstance.Get().ForTests((method, argTypes, args) => {

var call = new object[] { console, console.In, console.Out }.Select(x => new { t = x, m = x.GetType().GetMethod(method, argTypes) }).Where(x => x.m != null).First();

return call.m.Invoke(call.t, args);

});

}

}

public class TestConsole {

readonly MemoryStream output;

StreamWriter writer;

readonly MemoryStream input;

StreamReader reader;

public TestConsole(string input) {

this.input = new MemoryStream(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(input));

this.reader = new StreamReader(this.input);

this.output = new MemoryStream();

this.writer = new StreamWriter(this.output);

}

public TextWriter Out { get { return writer; } }

public TextReader In { get { return reader; } }

public string Output {

get {

if(writer != null) {

writer.Close();

writer = null;

}

return Encoding.UTF8.GetString(output.ToArray());

}

}

}

Pure I / O functions in C #. Tests

Let's start with a simple one:

[Test]

public void WriteChars() {

Setup("");

testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Write('A'));

testInst.AssertIO(1, () => Console.Write('B'));

Assert.AreEqual("AB", console.Output);

}

Note that not only the performance of a pure function,

AssertIO,but also side effects are tested here : the code is written ... Write('A') ... Write('B') ...,and it is expected that “AB” will be displayed on the screen. Let's try something more interesting. For example, we rearrange the calls

AssertIO.Since it AssertIOis a pure function, it may seem that the result (lack of executions) should not change. But this is not so: it is a different test, it has a different AppInstance, and therefore the result may change (although it may not change). In practice, it turns out that in this case nothing is output:[Test]

public void WriteCharsInBackOrder() {

Setup("");

Assert.Throws(() => testInst.AssertIO(1, () => Console.Write('B')));

Assert.Throws(() => testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Write('A')));

Assert.AreEqual("", console.Output);

}

A pure function should return the same result on the same set of arguments:

[Test]

public void WriteCharTwice() {

Setup("");

testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Write('A'));

testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Write('A'));

Assert.Throws(() => testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Write('B')));

Assert.AreEqual("A", console.Output);

}

If the conclusion failed for some reason, we should get an error in the form of execution:

[Test]

public void GetWriteError() {

Setup("");

console.Out.Close();

Assert.Throws(() => testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Write('A')));

Assert.Throws(() => testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Write('B')));

}

We also need at least one read test:

[Test]

public void ReadChar() {

Setup("123");

Assert.AreEqual((int)'1', testInst.AssertIO(0, () => Console.Read()));

Assert.AreEqual((int)'2', testInst.AssertIO(1, () => Console.Read()));

Assert.AreEqual((int)'3', testInst.AssertIO(2, () => Console.Read()));

Assert.AreEqual(-1, testInst.AssertIO(3, () => Console.Read()));

}

Pure I / O functions in C #. Implementation

We write an auxiliary class that will parse the passed linq expression and make a real call to the specified method with the specified parameters, using the passed

consoleDescriptor:The code

class IOOperation {

readonly string method;

readonly Type[] argTypes;

readonly object[] args;

public IOOperation(LambdaExpression callExpression) {

var methodExpr = (MethodCallExpression)callExpression.Body;

this.args = methodExpr.Arguments.Select(x => Expression.Lambda>(Expression.Convert(x, typeof(object))).Compile()()).ToArray();

this.method = methodExpr.Method.Name;

this.argTypes = methodExpr.Method.GetParameters().Select(x => x.ParameterType).ToArray();

}

public TResult Do(Func consoleDescriptor) {

return (TResult)consoleDescriptor(method, argTypes, args);

}

}

To track the same calls (as in the test

WriteCharTwice) it’s convenient to override Equals:The code

public static bool operator ==(IOOperation a, IOOperation b) {

bool aIsNull = ReferenceEquals(a, null);

bool bIsNull = ReferenceEquals(b, null);

return

aIsNull && bIsNull ||

!aIsNull && !bIsNull &&

string.Equals(a.method, b.method, StringComparison.Ordinal) &&

a.args.Length == b.args.Length &&

!a.args.Zip(b.args, Equals).Where(x => !x).Any();

}

public override int GetHashCode() { return method.GetHashCode() ^ args.Length; }

public static bool operator !=(IOOperation a, IOOperation b) { return !(a == b); }

public override bool Equals(object obj) { return this == obj as IOOperation; }

Now we can reduce two methods

AssertIOto one:public None AssertIO(int index, Expression ioExpression) {

return AssertIO(index, new IOOperation(ioExpression));

}

public TResult AssertIO(int index, Expression> ioExpression) {

return AssertIO(index, new IOOperation(ioExpression));

}

TResult AssertIO(int index, IOOperation operation); It remains to implement the last method - and the thing is done.

It is clear that we need to somehow cache the results of our calls to the native console. Add the necessary classes and fields:

The code

readonly List completedOperations = new List();

abstract class IOOperationResult { }

sealed class IOOperationResult : IOOperationResult {

readonly TResult returnValue;

readonly Exception exception;

public IOOperationResult(Func getResult) {

try {

returnValue = getResult();

exception = null;

} catch(Exception e) {

returnValue = default(TResult);

exception = e;

}

}

public TResult Result {

get {

if(exception != null)

throw new AggregateException(exception);

return returnValue;

}

}

}

abstract class IOOperationWithResult { }

sealed class IOOperationWithResult : IOOperationWithResult {

public IOOperationWithResult(IOOperation operation, IOOperationResult result) {

Operation = operation;

Result = result;

}

public readonly IOOperation Operation;

public readonly IOOperationResult Result;

}

Having done the preparatory work, we can finally write actually

AssertIO:The code

bool rejectOperations = false;

TResult AssertIO(int index, IOOperation operation) {

if(index < 0)

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException("index");

if(index < completedOperations.Count) {

var completedOperation = completedOperations[index] as IOOperationWithResult;

if(completedOperation == null || completedOperation.Operation != operation)

throw new ArgumentException("", "operation");

return completedOperation.Result.Result;

}

if(rejectOperations)

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException("index");

if(index == completedOperations.Count) {

var completedOperation = new IOOperationWithResult(operation, new IOOperationResult(() => operation.Do(consoleDescriptor)));

completedOperations.Add(completedOperation);

return completedOperation.Result.Result;

}

rejectOperations = true;

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException("index");

}

The algorithm is simple. If a request comes about the result of an already completed operation, then we go into the cache and check IOOperation. If we have a complete match, it means that the specified method was actually called with the specified parameters, and we return the result; and if there is a difference, the raise is quick. Further, if there is no operation in the cache yet and now is the right time to perform it, we perform the operation, add it to the cache along with the result, and return the result. If there is no operation in the cache and a time machine is required to perform it, nothing good will come of it, so it remains to fall by raising a special flag in advance

rejectOperations,to ensure the consistency of the method’s behavior during further calls.Such a simple implementation behaves in the same way as a possible implementation on pure functions, and ensures passing written (and unwritten) tests.

Monad IO

Now that we have pure non-monadic I / O functions, writing a monad

IOis no problem:The code

public sealed class IO {

readonly Func> func;

internal IO(Func> func) {

this.func = func;

}

internal RealWorld Execute(RealWorld index, out T result) {

var resultTuple = func(index);

result = resultTuple.Item2;

return resultTuple.Item1;

}

}

class RealWorld {

readonly AppInstance inst;

readonly int index;

public RealWorld(AppInstance inst, int index) {

this.inst = inst;

this.index = index;

}

public Tuple Do(Expression callExpression) {

return Tuple.Create(Yield(), inst.AssertIO(index, callExpression));

}

public Tuple Do(Expression> callExpression) {

return Tuple.Create(Yield(), inst.AssertIO(index, callExpression));

}

public RealWorld Yield() {

return new RealWorld(inst, index + 1);

}

}

We can even support the special monadic syntax available in C #.

(from ... in ... select ...). For this, in addition to our custom methods Return, you Dowill need to implement methods Selectand SelectMany(they should be called that way and have a certain signature - duck typing works):The code

public static class IO {

public static IO Return(T value) {

return new IO(x => Tuple.Create(x, value));

}

public static IO Select(this IO io, Func selector) {

return new IO(x => {

T t;

var index = io.Execute(x, out t);

return Tuple.Create(index, selector(t));

});

}

public static IO SelectMany(this IO io, Func> selector, Func projector) {

return new IO(x => {

T t;

var index = io.Execute(x, out t);

var ioc = selector(t);

C c;

var resultIndex = ioc.Execute(index, out c);

return Tuple.Create(resultIndex, projector(t, c));

});

}

public static IO Do(Expression callExpression) {

return new IO(x => x.Do(callExpression));

}

public static IO Do(Expression> callExpression) {

return new IO(x => x.Do(callExpression));

}

public static IO Handle(this IO io, Func> handler) {

return new IO(x => {

RealWorld rw;

T t;

try {

rw = io.Execute(x, out t);

} catch(Exception e) {

rw = handler(e).Execute(x.Yield(), out t);

}

return Tuple.Create(rw, t);

});

}

}

In addition to those mentioned, we added a very useful method

Handlethat allows you to continue working when an occurrence occurs. You will also need a “monad” entry point to the application:

public static class AppInstanceIOExtensions {

public static void DoMain(this AppInstance inst, Func> body) {

None result;

body().Execute(new RealWorld(inst, 0), out result);

}

}

Demonstration of the result

Let's write the simplest console application using the monad

IO:class Program {

static void Main(string[] args) {

AppInstance.Get().DoMain(IOMain);

}

static IO IOMain() {

return

from _ in IO.Do(() => Console.WriteLine("What is your name?"))

from name in IO.Do(() => Console.ReadLine())

let message = "Hi, " + name + "!"

from r in IO.Do(() => Console.WriteLine(message))

select r;

}

}

Result of work:

Full code on github: IOMonad .