Compiling and decompiling try-with-resources

Compiling and decompiling try-with-resources, or a story about how I fixed a bug and what came of it.

Some time ago, the backlog of a working draft was almost empty, and various research tasks surfaced. One of them sounded very intriguing: to fasten mutational testing to the project using PITest . On Habré there is already a very detailed review of this library (with examples and pictures). I will not retell this article in my own words, but still I recommend that you familiarize yourself with it in advance.

Some time ago, the backlog of a working draft was almost empty, and various research tasks surfaced. One of them sounded very intriguing: to fasten mutational testing to the project using PITest . On Habré there is already a very detailed review of this library (with examples and pictures). I will not retell this article in my own words, but still I recommend that you familiarize yourself with it in advance.

I admit that the idea of mutational testing, I fired up. With almost no extra effort, getting a tool for finding potentially dangerous places in your code is worth it! I immediately got down to business. At that time, the library was relatively young, and as a result, very crude: here you need to play a little with the maven configuration, and there - patch the plug-in for Sonar. However, after a while I was still able to verify the entire project. Result: hundreds of surviving mutations! Scale evolution on our build server.

Rolling up my sleeves, I plunged into work. In some tests, there is not enough verification of stubs, in others, instead of logic, it is generally not clear what is being tested. Edit, improve, rewrite. In general, the process began, but the number of surviving mutations did not decrease as rapidly as we wanted. The reason was simple: PIT gave a huge amount of false positives on the try-with-resources block . A short search showed that the bug is known , but still not fixed. Well, the library code is open. Why not persuade him and see what is the matter?

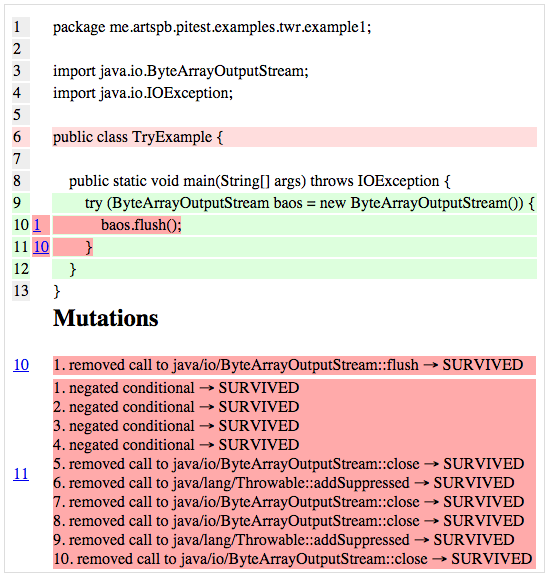

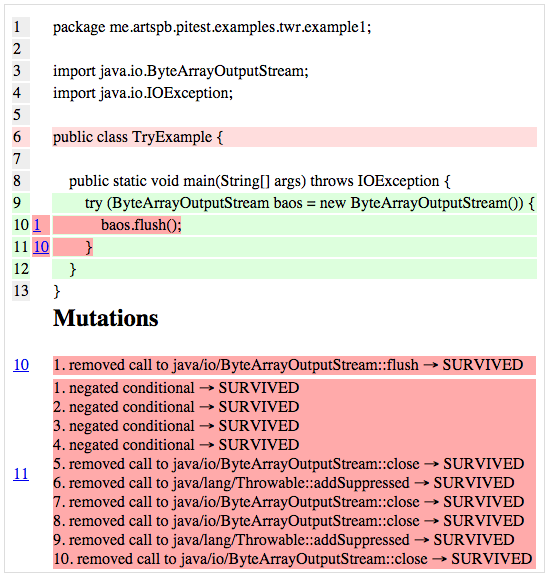

I threw a simple example , a unit test for it and ran PITest. The result is before you: instead of one, there are eleven mutations that survived, ten of which indicate a line with the “}” symbol. Calls to the close and addSupressed methods suggest that this line includes the code generated for the try-with-resources block. To confirm this conjecture, I decided to decompile the class file. To do this, I used the JD-GUI , although I would now recommend the built-in IntelliJ IDEA 14 decompiler .

The guess was confirmed, but the question remained: how did two try-with-resources lines turn into a dozen try-catch-finally lines? gvsmirnov bequeathed to us in any incomprehensible situation to download OpenJDK sources . This is what I did.

All code related to the try-with-resources compilation task is located between lines 1428 and 1580 of the Lower class . Javadoc tells us that this class is designed to translate syntactic sugar: no magic, only the simplest modifications to the syntax tree. Everything is in accordance with JLS 14.20.3 .

We figured out the compiler behavior. It remains to understand why the library is trying to mutate the code generated by the compiler and how it works. Rummaging through the source, I found out the following. PITest only manipulates bytecode loaded into RAM. It replaces the instructions according to certain rules, and then runs unit tests. For work with bytecode ASM is used .

The first idea was to intercept the line number of the class method visitGeneratedTryCatchBlock MethodVisitor , and then just tell the library what line should be ignored. Similar functionality has already been implemented.for finally block. However, I was surprised to learn that the visitGeneratedTryCatchBlock method does not exist. ASM does not distinguish between the code generated by the compiler and the code generated by the programmer. Ambush. I had to look into the bytecode, the output and formatting of which was kindly provided by Textifier .

The naive assumption that the try-catch-finally block is implemented at the JVM level has not been confirmed . There is no special instruction for it, only an exception table and goto between labels. It turns out that by standard means it will not work to recognize the generated block. Need to look for another solution.

Before starting to guess on coffee grounds, I decided to put bytecode marks on the decompiled class. That's what came out of it.

Two main ways of program execution are clearly emerging:

Underneath each other are labels whose code blocks match or almost match. In parentheses is the code that will be executed when the close method throws an exception. Similarly in square - when the flush method . Two ways turned out because the finally block was substituted by the compiler twice. Well, now, to completely break your visual parser: the labels in curly brackets refer to line 11. The false line PITest refers to the same line.

Here is the solution! A minimally repeating set of instructions should be highlighted. If such a set is found in the bytecode being tested, and even on one line, the generated code for the try-with-resources block is available. It doesn't sound very hard, but I decided to give it a try. Below is a list of instructions that I ended up with.

Something like this can be mapped to code in a finally block.

“Not so difficult,” I thought after several days of hard work. Threw a few more examples ; wrote tests that use them. Everything is fine, everything works. I tried to build PITest to run it on live code: the tests fell. Not the ones I wrote; others.

So, the code has moved from the “does not compile” stage to the “does not work” stage. One of the tests that existed before this fell. Rolled back - it works. Inside the test, the Java7TryWithResources.class.bin file that was already in the project is checked . Having printed the bytecode, I could not believe my eyes: a completely different order of instructions was used to compile try-with-resources!

Trying not to panic, I began to check all the compilers at hand. I worked with javac from Oracle JDK, javac from OpenJDK expectedly gave a similar result. I tried different versions: to no avail. It was the turn of compilers that were not at hand. Eclipse Compiler for Java, ECJ. Compiled, printed bytecode - at first glance it looks like the one I'm looking for.

After that, I decided to decompile the resulting class file. The result of the decompiler refused to compile back. Well, nothing, you can already work with this. Hands bringing the program code in accordance with the bytecode, I got the following.

ECJ takes a completely different approach to compiling try-with-resources. Labels are noticeably smaller, blocks of code are noticeably larger. Instead of a bloated table, exceptions are simply thrown to the next level. In the more complicated examples, you can notice that it turns out a sort of nesting doll.

What is under the hood? I again went to download the source, this time ECJ . Compilation of the try statement is hidden in the TryStatement file . This time no trees, only opcodes, only hardcore. The bytecode responsible for try-with-resources is generated between lines 500 and 604. From the history of commits, it is clearly seen that the body of the try block was simply framed by a chain of calls to create and close resources.

Because if there is no substitution of the finally block, then there is no duplication of code. However, due to nesting, the same actions are repeated for different exceptions. I took advantage of this. The set of instructions for ECJ is as follows.

And so the corresponding java code looks like.

What about the rest of the compilers? It turned out that AspectJ generates almost the same bytecode as ECJ. For him, there was no need to invent a separate sequence. I could not download the compiler from IBM (and I didn’t really want to). Other compilers were ignored due to low prevalence.

An attentive reader has already noticed that the set of instructions for javac does not take into account one nuance. To call the methods of the class and the interface, different instructions are actually used: INVOKEVIRTUAL and INVOKEINTERFACE, respectively. The implementation described above takes into account only the first case and does not take into account the second. Well, nothing, it's not hard to fix.

So what is the result?

First, the main result of the work was a patch that fixes the bug mentioned at the beginning of the article. Almost all of the code fits in one class (not counting the tests), which currently looks like this: TryWithResourcesMethodVisitor . I urge everyone to criticize and propose their best options for solving this problem.

Secondly, I found out what are the ways to compile a try-with-resources block. As a result, I figured out what try-catch-finally looks like at the bytecode level. Well, a by-product was the translation of an article that I mentioned above in the text.

Thirdly, I wrote this article where I told you everything. Perhaps now one of you will be able to increase the fundamental coefficient of squandering using the acquired knowledge.

And where is the use and morality, you ask? I leave their search to the reader. I only note that I enjoyed while writing this article. Hope you got it from reading. See you soon!

PS As a bonus, I suggest looking at early proposals for the implementation of try-with-resources from Joshua Bloch.

It looks funny.

Introduction

Some time ago, the backlog of a working draft was almost empty, and various research tasks surfaced. One of them sounded very intriguing: to fasten mutational testing to the project using PITest . On Habré there is already a very detailed review of this library (with examples and pictures). I will not retell this article in my own words, but still I recommend that you familiarize yourself with it in advance.

Some time ago, the backlog of a working draft was almost empty, and various research tasks surfaced. One of them sounded very intriguing: to fasten mutational testing to the project using PITest . On Habré there is already a very detailed review of this library (with examples and pictures). I will not retell this article in my own words, but still I recommend that you familiarize yourself with it in advance.I admit that the idea of mutational testing, I fired up. With almost no extra effort, getting a tool for finding potentially dangerous places in your code is worth it! I immediately got down to business. At that time, the library was relatively young, and as a result, very crude: here you need to play a little with the maven configuration, and there - patch the plug-in for Sonar. However, after a while I was still able to verify the entire project. Result: hundreds of surviving mutations! Scale evolution on our build server.

Rolling up my sleeves, I plunged into work. In some tests, there is not enough verification of stubs, in others, instead of logic, it is generally not clear what is being tested. Edit, improve, rewrite. In general, the process began, but the number of surviving mutations did not decrease as rapidly as we wanted. The reason was simple: PIT gave a huge amount of false positives on the try-with-resources block . A short search showed that the bug is known , but still not fixed. Well, the library code is open. Why not persuade him and see what is the matter?

We understand the reasons

I threw a simple example , a unit test for it and ran PITest. The result is before you: instead of one, there are eleven mutations that survived, ten of which indicate a line with the “}” symbol. Calls to the close and addSupressed methods suggest that this line includes the code generated for the try-with-resources block. To confirm this conjecture, I decided to decompile the class file. To do this, I used the JD-GUI , although I would now recommend the built-in IntelliJ IDEA 14 decompiler .

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

ByteArrayOutputStream baos = new ByteArrayOutputStream();

Throwable var2 = null;

try {

baos.flush();

} catch (Throwable var11) {

var2 = var11;

throw var11;

} finally {

if (baos != null) {

if (var2 != null) {

try {

baos.close();

} catch (Throwable var10) {

var2.addSuppressed(var10);

}

} else {

baos.close();

}

}

}

}The guess was confirmed, but the question remained: how did two try-with-resources lines turn into a dozen try-catch-finally lines? gvsmirnov bequeathed to us in any incomprehensible situation to download OpenJDK sources . This is what I did.

All code related to the try-with-resources compilation task is located between lines 1428 and 1580 of the Lower class . Javadoc tells us that this class is designed to translate syntactic sugar: no magic, only the simplest modifications to the syntax tree. Everything is in accordance with JLS 14.20.3 .

We figured out the compiler behavior. It remains to understand why the library is trying to mutate the code generated by the compiler and how it works. Rummaging through the source, I found out the following. PITest only manipulates bytecode loaded into RAM. It replaces the instructions according to certain rules, and then runs unit tests. For work with bytecode ASM is used .

The first idea was to intercept the line number of the class method visitGeneratedTryCatchBlock MethodVisitor , and then just tell the library what line should be ignored. Similar functionality has already been implemented.for finally block. However, I was surprised to learn that the visitGeneratedTryCatchBlock method does not exist. ASM does not distinguish between the code generated by the compiler and the code generated by the programmer. Ambush. I had to look into the bytecode, the output and formatting of which was kindly provided by Textifier .

The bytecode of the main method of the TryExample class

// access flags 0x9

public static main([Ljava/lang/String;)V throws java/io/IOException

TRYCATCHBLOCK L0 L1 L2 java/lang/Throwable

TRYCATCHBLOCK L3 L4 L5 java/lang/Throwable

TRYCATCHBLOCK L3 L4 L6 null

TRYCATCHBLOCK L7 L8 L9 java/lang/Throwable

TRYCATCHBLOCK L5 L10 L6 null

L11

LINENUMBER 12 L11

NEW java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream

DUP

INVOKESPECIAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream. ()V

ASTORE 1

L12

ACONST_NULL

ASTORE 2

L3

LINENUMBER 13 L3

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.flush ()V

L4

LINENUMBER 14 L4

ALOAD 1

IFNULL L13

ALOAD 2

IFNULL L14

L0

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.close ()V

L1

GOTO L13

L2

FRAME FULL [[Ljava/lang/String; java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream java/lang/Throwable] [java/lang/Throwable]

ASTORE 3

L15

ALOAD 2

ALOAD 3

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/lang/Throwable.addSuppressed (Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V

L16

GOTO L13

L14

FRAME SAME

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.close ()V

GOTO L13

L5

LINENUMBER 12 L5

FRAME SAME1 java/lang/Throwable

ASTORE 3

ALOAD 3

ASTORE 2

ALOAD 3

ATHROW

L6

LINENUMBER 14 L6

FRAME SAME1 java/lang/Throwable

ASTORE 4

L10

ALOAD 1

IFNULL L17

ALOAD 2

IFNULL L18

L7

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.close ()V

L8

GOTO L17

L9

FRAME FULL [[Ljava/lang/String; java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream java/lang/Throwable T java/lang/Throwable] [java/lang/Throwable]

ASTORE 5

L19

ALOAD 2

ALOAD 5

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/lang/Throwable.addSuppressed (Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V

L20

GOTO L17

L18

FRAME SAME

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.close ()V

L17

FRAME SAME

ALOAD 4

ATHROW

L13

LINENUMBER 15 L13

FRAME FULL [[Ljava/lang/String;] []

RETURN

L21

LOCALVARIABLE x2 Ljava/lang/Throwable; L15 L16 3

LOCALVARIABLE x2 Ljava/lang/Throwable; L19 L20 5

LOCALVARIABLE baos Ljava/io/ByteArrayOutputStream; L12 L13 1

LOCALVARIABLE args [Ljava/lang/String; L11 L21 0

MAXSTACK = 2

MAXLOCALS = 6 The naive assumption that the try-catch-finally block is implemented at the JVM level has not been confirmed . There is no special instruction for it, only an exception table and goto between labels. It turns out that by standard means it will not work to recognize the generated block. Need to look for another solution.

What if…

Before starting to guess on coffee grounds, I decided to put bytecode marks on the decompiled class. That's what came out of it.

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

ByteArrayOutputStream baos = new ByteArrayOutputStream(); // L11

Throwable primaryExc = null; // L12

try {

baos.flush(); // L3

} catch (Throwable t) { // L5

primaryExc = t;

throw t;

} finally { // L6

if (baos != null) { // L4 L10

if (primaryExc != null) {

try {

baos.close(); // L0 L7

} catch (Throwable suppressedExc) { // L2 L9

primaryExc.addSuppressed(suppressedExc); // L15 L19

} // L1 L16 L8 L20

} else {

baos.close(); // L14 L18

}

} // L17

} // L13

}Two main ways of program execution are clearly emerging:

L11 L12 L3 {L4 [L0 (L2 L15 L16) L1] L14} L13

L11 L12 L3 [L5 {L6] L10 [L7 (L9 L19 L20) L8] L18 L17}

Underneath each other are labels whose code blocks match or almost match. In parentheses is the code that will be executed when the close method throws an exception. Similarly in square - when the flush method . Two ways turned out because the finally block was substituted by the compiler twice. Well, now, to completely break your visual parser: the labels in curly brackets refer to line 11. The false line PITest refers to the same line.

Here is the solution! A minimally repeating set of instructions should be highlighted. If such a set is found in the bytecode being tested, and even on one line, the generated code for the try-with-resources block is available. It doesn't sound very hard, but I decided to give it a try. Below is a list of instructions that I ended up with.

private static final List JAVAC_CLASS_INS_SEQUENCE = Arrays.asList(

ASTORE, // store throwable

ALOAD, IFNULL, // closeable != null

ALOAD, IFNULL, // localThrowable2 != null

ALOAD, INVOKEVIRTUAL, GOTO, // closeable.close()

ASTORE, // Throwable x2

ALOAD, ALOAD, INVOKEVIRTUAL, GOTO, // localThrowable2.addSuppressed(x2)

ALOAD, INVOKEVIRTUAL, // closeable.close()

ALOAD, ATHROW); // throw throwable Something like this can be mapped to code in a finally block.

} finally {

if (closeable != null) { // IFNULL

if (localThrowable2 != null) { // IFNULL

try {

closeable.close(); // INVOKEVIRTUAL or INVOKEINTERFACE

} catch (Throwable x2) {

localThrowable2.addSuppressed(x2); // INVOKEVIRTUAL

}

} else {

closeable.close(); // INVOKEVIRTUAL or INVOKEINTERFACE

}

}

} // ATHROW“Not so difficult,” I thought after several days of hard work. Threw a few more examples ; wrote tests that use them. Everything is fine, everything works. I tried to build PITest to run it on live code: the tests fell. Not the ones I wrote; others.

Compilers are different

So, the code has moved from the “does not compile” stage to the “does not work” stage. One of the tests that existed before this fell. Rolled back - it works. Inside the test, the Java7TryWithResources.class.bin file that was already in the project is checked . Having printed the bytecode, I could not believe my eyes: a completely different order of instructions was used to compile try-with-resources!

Trying not to panic, I began to check all the compilers at hand. I worked with javac from Oracle JDK, javac from OpenJDK expectedly gave a similar result. I tried different versions: to no avail. It was the turn of compilers that were not at hand. Eclipse Compiler for Java, ECJ. Compiled, printed bytecode - at first glance it looks like the one I'm looking for.

The bytecode of the main method of the TryExample by ECJ class

// access flags 0x9

public static main([Ljava/lang/String;)V throws java/io/IOException

TRYCATCHBLOCK L0 L1 L2 null

TRYCATCHBLOCK L3 L4 L4 null

L5

LINENUMBER 12 L5

ACONST_NULL

ASTORE 1

ACONST_NULL

ASTORE 2

L3

NEW java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream

DUP

INVOKESPECIAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream. ()V

ASTORE 3

L0

LINENUMBER 13 L0

ALOAD 3

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.flush ()V

L1

LINENUMBER 14 L1

ALOAD 3

IFNULL L6

ALOAD 3

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.close ()V

GOTO L6

L2

FRAME FULL [[Ljava/lang/String; java/lang/Throwable java/lang/Throwable java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream] [java/lang/Throwable]

ASTORE 1

ALOAD 3

IFNULL L7

ALOAD 3

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/io/ByteArrayOutputStream.close ()V

L7

FRAME CHOP 1

ALOAD 1

ATHROW

L4

FRAME SAME1 java/lang/Throwable

ASTORE 2

ALOAD 1

IFNONNULL L8

ALOAD 2

ASTORE 1

GOTO L9

L8

FRAME SAME

ALOAD 1

ALOAD 2

IF_ACMPEQ L9

ALOAD 1

ALOAD 2

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/lang/Throwable.addSuppressed (Ljava/lang/Throwable;)V

L9

FRAME SAME

ALOAD 1

ATHROW

L6

LINENUMBER 15 L6

FRAME CHOP 2

RETURN

MAXSTACK = 2

MAXLOCALS = 4 After that, I decided to decompile the resulting class file. The result of the decompiler refused to compile back. Well, nothing, you can already work with this. Hands bringing the program code in accordance with the bytecode, I got the following.

public static void main(String[] paramArrayOfString) throws Throwable {

Throwable primaryExceptionVariable = null; // L5

Throwable caughtThrowableVariable = null;

try {

ByteArrayOutputStream baos = new ByteArrayOutputStream(); // L3

try {

baos.flush(); // L0

} catch (Throwable t) {

primaryExceptionVariable = t; // L2

throw primaryExceptionVariable; // L7

} finally {

if (baos != null) { // L1

baos.close();

}

}

} catch (Throwable t) {

caughtThrowableVariable = t; // L4

if (primaryExceptionVariable == null) {

primaryExceptionVariable = caughtThrowableVariable;

} else if (primaryExceptionVariable != caughtThrowableVariable) { // L8

primaryExceptionVariable.addSuppressed(caughtThrowableVariable);

}

throw primaryExceptionVariable; // L9

} // L6

}ECJ takes a completely different approach to compiling try-with-resources. Labels are noticeably smaller, blocks of code are noticeably larger. Instead of a bloated table, exceptions are simply thrown to the next level. In the more complicated examples, you can notice that it turns out a sort of nesting doll.

What is under the hood? I again went to download the source, this time ECJ . Compilation of the try statement is hidden in the TryStatement file . This time no trees, only opcodes, only hardcore. The bytecode responsible for try-with-resources is generated between lines 500 and 604. From the history of commits, it is clearly seen that the body of the try block was simply framed by a chain of calls to create and close resources.

Because if there is no substitution of the finally block, then there is no duplication of code. However, due to nesting, the same actions are repeated for different exceptions. I took advantage of this. The set of instructions for ECJ is as follows.

private static final List ECJ_INS_SEQUENCE = Arrays.asList(

ASTORE, // store throwable2

ALOAD, IFNONNULL, // if (throwable1 == null)

ALOAD, ASTORE, GOTO, // throwable1 = throwable2;

ALOAD, ALOAD, IF_ACMPEQ, // if (throwable1 != throwable2) {

ALOAD, ALOAD, INVOKEVIRTUAL, // throwable1.addSuppressed(throwable2)

ALOAD, ATHROW); // throw throwable1 And so the corresponding java code looks like.

if (throwable1 == null) { // IFNONNULL

throwable1 = throwable2;

} else {

if (throwable1 != throwable2) { // IF_ACMPEQ

throwable1.addSuppressed(throwable2); // INVOKEVIRTUAL

}

} // ATHROWWhat about the rest of the compilers? It turned out that AspectJ generates almost the same bytecode as ECJ. For him, there was no need to invent a separate sequence. I could not download the compiler from IBM (and I didn’t really want to). Other compilers were ignored due to low prevalence.

results

An attentive reader has already noticed that the set of instructions for javac does not take into account one nuance. To call the methods of the class and the interface, different instructions are actually used: INVOKEVIRTUAL and INVOKEINTERFACE, respectively. The implementation described above takes into account only the first case and does not take into account the second. Well, nothing, it's not hard to fix.

So what is the result?

First, the main result of the work was a patch that fixes the bug mentioned at the beginning of the article. Almost all of the code fits in one class (not counting the tests), which currently looks like this: TryWithResourcesMethodVisitor . I urge everyone to criticize and propose their best options for solving this problem.

Secondly, I found out what are the ways to compile a try-with-resources block. As a result, I figured out what try-catch-finally looks like at the bytecode level. Well, a by-product was the translation of an article that I mentioned above in the text.

Thirdly, I wrote this article where I told you everything. Perhaps now one of you will be able to increase the fundamental coefficient of squandering using the acquired knowledge.

And where is the use and morality, you ask? I leave their search to the reader. I only note that I enjoyed while writing this article. Hope you got it from reading. See you soon!

PS As a bonus, I suggest looking at early proposals for the implementation of try-with-resources from Joshua Bloch.

Stumbled on original ARM block (try-with-resources) proposals, if anyone's curious. V1: https://t.co/Qngv2STN1W , V2: https://t.co/YiR1RvyZWg

- Joshua Bloch (@joshbloch) June 13, 2015It looks funny.

{

final LocalVariableDeclaration ;

boolean #suppressSecondaryException = false;

try Block catch (final Throwable #t) {

#suppressSecondaryException = true;

throw #t;

} finally {

if (#suppressSecondaryException)

try { localVar.close(); } catch(Exception #ignore) { }

else

localVar.close();

}

}